This summer day dress was in the 'must-have' style of the mid-1850s. It was known as a crinoline, from the wide, bell-shaped skirt. Women of all ages and all classes of society wore crinoline dresses in Victoria, though they were not very practical for everyday tasks about the house. It is especially hard to imagine living in a tent on the goldfields in such a dress!

This particular dress is made in one piece, with the skirt attached to the waistline. It is made of a printed cotton fabric, probably best described as a calico and the bodice is also fully lined in a heavier calico. The shape of the bodice, high to the neck and with long sleeves, tells us that this was a day dress, although perhaps more a dress for afternoon visits or shopping expeditions than for wearing at home around the house.

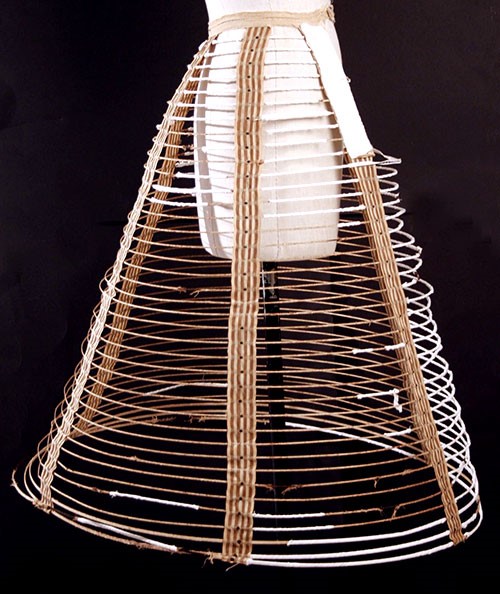

But it is the skirt that is the real focus of this dress. It is very full, measuring 332 cm at the hemline, and is made by gathering seven lengths of material in tiny pleats at the waist. Three tiers of flounces add both fullness and a scalloped appearance to the skirt. Such flounces were very popular in the mid-1850s. Although it seems very large, this was a relatively modest crinoline. Later in the decade skirts expanded even further, although by this time they were supported by wire 'crinoline' frames worn underneath. This was a great relief to women. Before the invention of the crinoline frame, skirts like this one were held out by wearing many petticoats underneath. As many as six were worn! At least one of the petticoats may have been padded with horsehair to stiffen it.

The crinoline dress could look very elegant, but its size also made it a dangerous fashion, especially in an era of open fires. Newspapers of the day often carried stories of women being badly burnt when their skirts caught fire.

The fashionable style

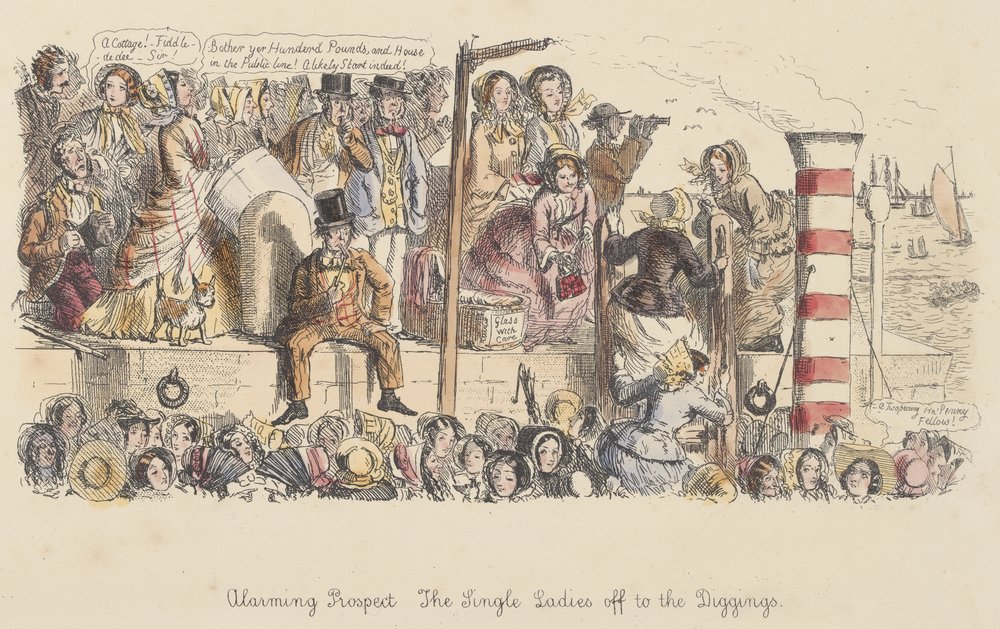

Although Australia was a long way from the fashion centres of Paris and London, information about the latest styles in dress arrived with each boatload of new immigrants, while detailed fashion notes in the daily newspapers helped to keep Australian women up-to-date. Illustrations from the time, both serious and satirical, make it clear that the crinoline form of dress was swiftly adopted in Victoria, however inappropriate it may have been to conditions on the goldfields.

There is also evidence that dresses, ready to be 'made up', were sent out from England to family members in the colonies. Whether these were dress lengths, or cut-out pieces ready to be assembled, is not clear.

Many commentators on goldfields life made reference to standards of dress. Some of these noted the 'levelling' experience of gold getting, with men and masters dressed alike as they laboured at their claims. But others emphasised the high standards of dress at more formal occasions, with many 'ladies' in particular dressed in the latest fashions.

Then as now, what distinguished the wealthy from all but the very poor was probably more the quality of the fabrics and tailoring, the richness of the trimmings, and no doubt the general bearing and behaviour of the wearer, than the overall shape of the dress, although the width of the crinoline could also be a marker. Crinolines required an inordinate amount of material, especially those with flounced skirts. We estimate that there are more than 14 yards (13 metres) of fabric in this dress, with seven lengths of fabric in each of the two flounces. It required a large investment, in both materials and time, to make a dress like this. This particular dress is made of a robust cotton fabric, (perhaps cambric) with calico lining. It is not an especially fine dress, despite the flounces, and may well have been worn by a woman of the middling class.

Making a dress in the 1850s

This dress is sewn entirely by hand. That was common in the early 1850s, although within ten years or so the sewing machine would be making inroads on both domestic and professional sewing. It is impossible to tell whether this particular dress was made at home, or sewn by a professional dressmaker. While the quality of the stitching is high, with even stitches averaging only 1.5 mm in length throughout, a competent seamstress could have achieved that at home.

Almost every woman learned to sew at this time - of necessity. Clothing was expensive. It was carefully preserved, altered as fashions changed (or a woman's shape changed), mended when worn or torn. A dress like this was a big investment, in materials and time.

The bodice is constructed in several pieces, with each seam double sewn for strength. The neckline is high, with a narrow piped edging and the bodice fastens at the front with hooks and eyelet holes. A piped waistline extends to a point below the natural waistline, in a style that was fashionable until the mid-1850s, while the front of the bodice is gathered in soft pleats from the shoulder seams, ending in a rouched section at the front waist. The back of the bodice is shaped in three curved sections to fit the figure closely, while the shoulder seams are set back from the natural shoulder line to create the fashionable sloped effect. The sleeves are set into the bodice just off the natural shoulder. All seams are finished to sit flat and there are no bones inserted in the seams. Both bodice and sleeves are lined with calico. The inner circumference (fastened) at the natural waist is about 63 cm (25 inches).

Sleeves in the pagoda style

The sleeves are in the fashionable pagoda style, fitting closely at the top of the arm, before widening out in two open, flounced sections falling from above the elbow. They may have been worn with white cotton undersleeves, either open or closed. [show the sleeves] Such sleeves must have been completely impractical for many of the messier or more strenuous household tasks like washing up, washing or baking and presumably were either covered, pinned out of the way, or worn only once such tasks were finished. It is also possible that the woman who wore this dress employed servants to do those tasks for her. Sleeves like this may have been another indicator that the wearer did not have to perform such messy household tasks, though once again, there is evidence of their wide adoption.

Expanding skirts

Much of the focus of these dresses was on the width of the skirt, in this case emphasised by two deep flounces. The skirt is very full, composed of seven lengths of material, with the fullness created by dozens of tiny pleats, first 'gathered' with running stitches, then stitched individually in place at the waist using a technique known as 'hand stroking' - so called because the seamstress 'stroked' the needle along the edge of each pleat to create a sharp edge, after attaching the pleat with a hemming stitch. It was also known as cartridge pleating. A short additional section of fabric is similarly gathered and inserted under the waistline on the inside, presumably to create additional fullness. At the top of the skirt a length of material is pleated into the waist and curved at the front to create a peplum effect, at the same time mimicking the effect of a flounce. Two deep flounces, comprised of seven individual lengths of material joined selvage to selvage, are gathered and attached to the skirt with a running stitch seam. They slope towards the back, to create additional length at the back of the skirt. The skirt is actually 10 cm longer at the back than the front. It is unlined.

How long would it take to sew?

We have speculated about the sheer amount of sewing involved in making a dress like this one. One count estimated that on the single seams there are approximately 46 stitches per 10 cm. Based on that count there are well over 5,000 stitches in the skirt alone. We don't know how long a woman at home might have taken to complete a dress in this style, but some estimates at the time suggested that a professional dressmaker might spend 14 hours sewing a crinoline. Obviously some tasks, like the fine piping, would have taken more time than others to complete. Fourteen hours seems little enough time to us for all of this work!

Underclothing

For most of the nineteenth century the shape of the dress was determined by the underclothing worn beneath. Both the quantity and the nature of this underclothing varied from decade to decade, but in the early-mid 1850s it was multi-layered. The first layer was a chemise or shift- a sleeveless garment in cotton or linen (or more rarely silk), that was gathered onto a neck-band and extended to about the knee. Over this was worn a corset, shaped with long whalebones and laced at the back. A wide busk in wood or whalebone and generally about 4 cm wide was inserted at the centre front. Initially a flap of the chemise folded down over the top of the corset to conceal it. Later a separate garment known as a camisole was worn. This was generally sleeveless, front-fastening and fitted to the waist.

The corset encased the body from just under the bust to about mid-thigh and was responsible for the shape of the torso. Much was written at the time about tight-lacing and the desire of women to achieve the smallest possible waist, but many actual dresses suggest that this stereotype was exaggerated. The waist measurement of this dress is about 25 inches (63 cm) - a 'normal' measurement even by today's standards. Admittedly this bodice was worn over several layers of underclothing!

Women at this time also began to wear drawers, or pantaloons more commonly. As the skirts expanded, the dangers of accidental exposure increased. For many decades these drawers were open at the inner seams, for the sake of hygiene. They were generally made of linen or cotton and at this time were fairly plain.

Over all of this women wore several petticoats, to support the desired fullness of the skirt. In the early 1850s as many as five or six petticoats might be worn, to create the desired shape. Petticoats generally mimicked the shape of the dress they supported. In mid-century this meant a pointed waistline with the fabric tightly gathered onto a waistband, and tied or buttoned at the back. Most were waist length. The earliest 'crinoline' petticoats were padded with bands of horsehair as additional stiffening, but cotton petticoats, with insertions of cord or stiffened fabric were also worn. From 1856-7 a new invention, the crinoline frame, appeared. This light construction of graduated whalebone or steel hoops supported the fullness of the skirts, while liberating the wearer from the layers of petticoats worn before. A single petticoat might be worn over the frame to mask the hoops. This lightened the weight of clothing women wore considerably. Stockings, knitted in cotton, wool, or, if the wearer was very wealthy, in fine silk, covered the feet and the legs. And finally - the dress went on over everything else, along with whatever outer clothing was considered necessary - mantles, shawls, bonnets and gloves. It doesn't require much imagination to suggest that Australia's summers must have been extremely uncomfortable for many women!

The dangers of the crinoline fashion

Crinoline frames could support skirts of great width, but they required some management. Light and buoyant, they tended to sway with the movement of the wearer, and could blow up or tilt in high winds. Many cartoons pointed to the havoc these wide skirts might cause- not to mention the occasional embarrassment. But there were more serious implications too. Even a skirt of this moderate width, probably made before the introduction of the crinoline frame, must have made moving around in confined spaces difficult and potentially dangerous. Perhaps Victorian women saved their full petticoats and crinoline frames for walking out, but there were enough instances of accidents to suggest that this was not always the case. The full skirts were especially dangerous near fire and there were many tragic accidents involving both women and older girls who died of burns after their skirts caught fire.

Working women

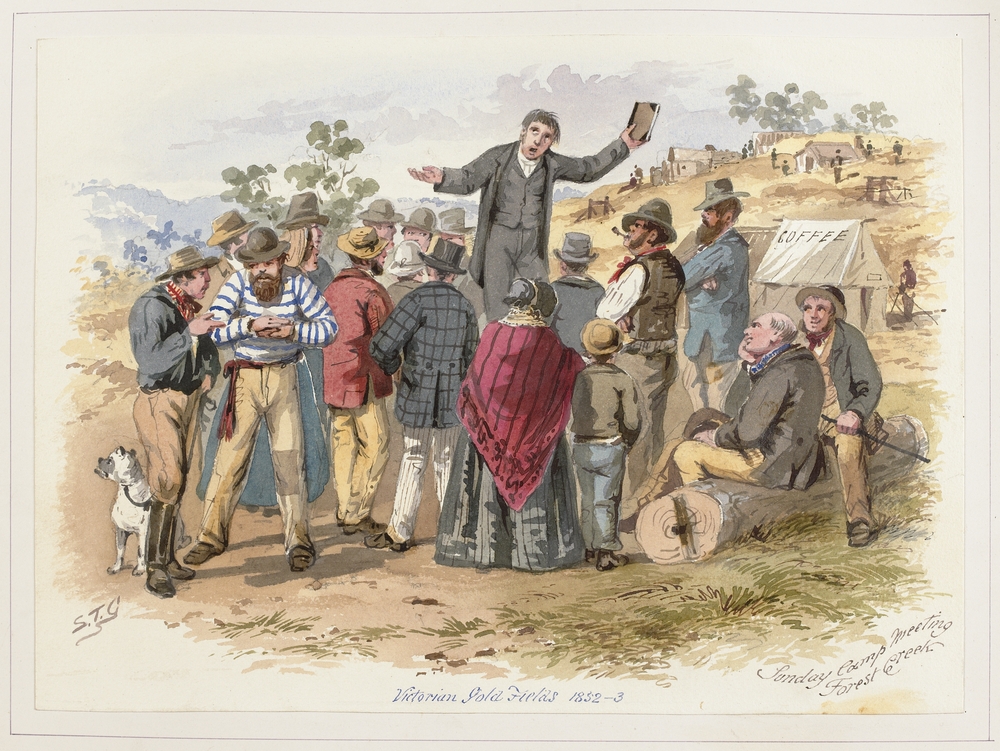

The pictorial evidence for the adoption of these fashions by working women is contradictory. S.T. Gill and other colonial artists depicted women of all walks of life in their sketches of the goldfields and these show a variety of styles of dress. The woman helping her husband at his gold claim in Zealous Gold Diggers has modest skirts, as does the woman tending her cooking fire in Digger's Hut, Bark & Canvas, or the woman serving grog at the Sly Grog Shanty. The women shown attending the Sunday Camp Meeting on the other hand, wear the fashionably full skirted dresses, while Gill's satirical Digger's Wife in Full Dress pokes fun at the frilled and flounced apparition stepping out with her silk parasol and her nose in the air! Both the Digger's Wife and another woman shown in this sketch must hold their full skirts clear of the mud, revealing a glimpse of shapely ankle. Almost certainly working women who could afford several dresses reserved their finer crinoline skirts for public occasions. Their working clothes were probably less fashionable, and more practical.

Caring for clothing

Laundering clothing was an arduous business in the nineteenth century. Generally laundry was boiled in tubs or coppers, then rinsed by hand and wrung out by hand or through a mangle. But not all fabrics washed well at this time. Wool, in particular, was prone to shrink in the wash and probably for this reason many immigrants made a point of requesting that their families send them materials for summer clothing in particular that would wash. It is very difficult to know how often people washed their clothes at this time. Certainly underclothing was washed regularly, as were men's cotton or linen shirts, but how often might a woman have washed a dress as large and complex as this one? We simply don't know. There is clear evidence that the dress has been worn - there is perspiration staining under the arms and the hems are slightly soiled - but whether it was washed regularly, or even at all, we can't know. One thing is certain, the ironing involved in a dress like this would have been a sizeable chore! Often it seems clothing was first thoroughly brushed and then aired. Washing might have been an occasional, rather than a routine, occurrence.

How many dresses did women own?

Of course this depended entirely on the means of the woman. Very wealthy women might own dozens of dresses. Such women routinely changed at least three times daily, wearing a 'morning' dress at home in the morning, an 'afternoon' dress for making or receiving calls, or shopping and an evening dress for a formal dinner or an evening function. Then there were ball dresses, riding dresses, and so on.

Women of the 'middling' classes, or respectable tradesmen's wives had less clothing altogether. Some sources make it clear that such women owned several dresses, but perhaps no more than two or three for each season.

We have some indication of the minimum amount of clothing considered necessary for poor immigrants from the requirements of the various immigration schemes. The Immigrants' Guide to Australia for 1853 noted that bounty immigrants were required to bring on board with them six shifts, two flannel petticoats, six pair of stockings, two pairs of shoes and two gowns, along with towels and soap. We can assume that the two gowns envisaged one for summer and one for winter. There would be no changes! Since laundering was not possible on board, it is probably safe to assume that the shifts and stockings were worn as long as possible and then put aside until the ship landed. The 'towels' mentioned for women (although not for men) were probably intended for menstruation rather than bathing.

Below is a Facebook live talk about this dress, given by Margaret Anderson, Director of the Old Treasury Building.

Further reading

Anne Buck Victorian Costume and Costume Accessories, Rev. ed., London, Bedford, 1984

Australian Dress Register, http://www.australiandressregister.org

Margaret Anderson, 'Mrs Charles Clacy, Lola Montez and Poll the Grogseller: Glimpses of Women on the Early Victorian Goldfields', in Iain McCalman, Andrew Reeves & Alexander Cook (eds) Gold: Forgotten Histories and Lost Objects of Australia Cambridge University Press, 2001, pp. 225-49.

John Capper The Immigrants' Guide to Australia Liverpool, George Phillip & Son, 1853

Marion Fletcher Costume in Australia, 1788-1901 Melbourne, OUP, 1984

Margaret Maynard Fashioned from Penury: Dress as Cultural Practice in Colonial Australia Cambridge University Press, 1994

Penny Russell A Wish of Distinction: Colonial Gentility and Femininity Melbourne University Press, 1994.