The family home is for many (probably most) Australians the largest and most expensive of the acquisitions or ‘belongings’ that they will accumulate during their lives. It is also the place where people keep most of their other belongings, from their underwear drawer to their kitchen cupboards and from their television set to their car/s (whether outside, under a carport or in a garage).

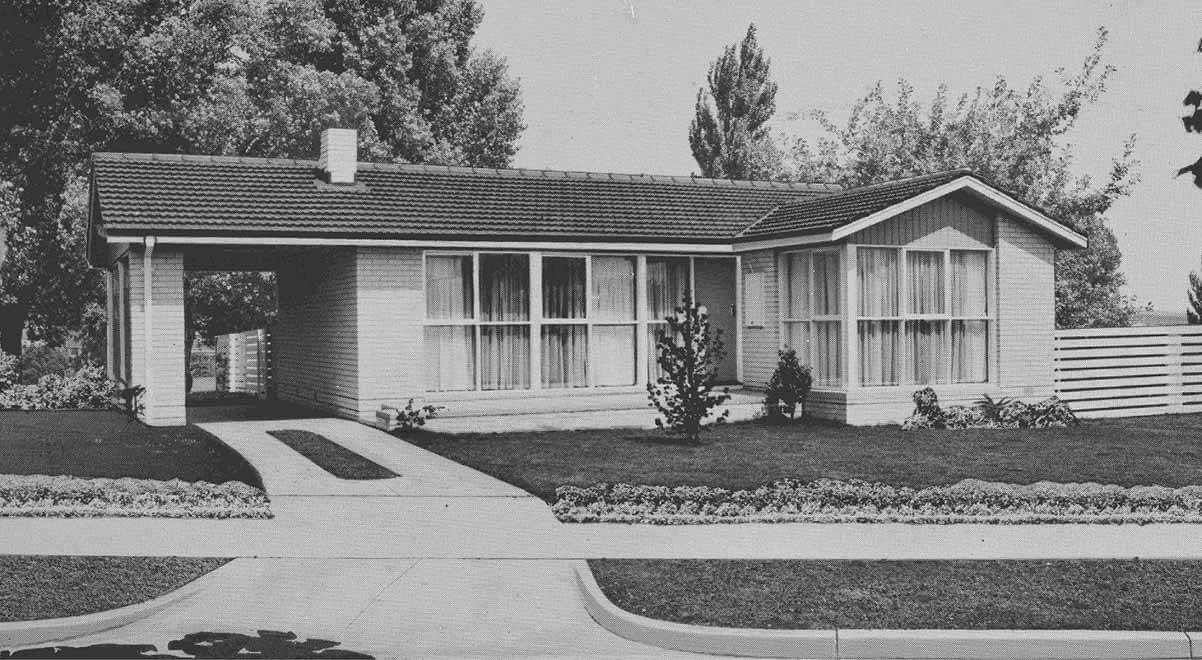

For a significant number of Australians who acquired a home from the 1950s to the 1980s, that home was built by the AV Jennings company and was therefore part of an extraordinary sociological and economic phenomenon that changed how Australians lived.

Between the 1950s and 1980s there was a revolution in the average Australian family home in size, style, fixtures and fittings, and in the possessions found there. Most new homes were sited in ever-increasing sprawls around the capital cities, and a high proportion were on housing estates developed by the AV Jennings company. The name of AV Jennings is indelibly inscribed in the consciousness of people who lived in Australia during the period, as it had arguably more influence on the Australian home than any other entity.

Jennings had emerged as a small but rapidly expanding private home builder in 1930s Melbourne but had moved to larger construction work and government housing in several states during and after the 1939-45 War. In the mid-1950s the company decided to return to private housing with a small experimental estate in the Melbourne suburb of Nunawading and within two years six estates had been developed in Melbourne’s east and south-east. The hunger for homes in the 1950s to 1980s meant that the company expanded rapidly over the next three decades and would in time be operating in every state and territory. By the end of the 1960s Jennings had already become the largest home builder in Australia, a status that it essentially retained through to the end of the 1980s.

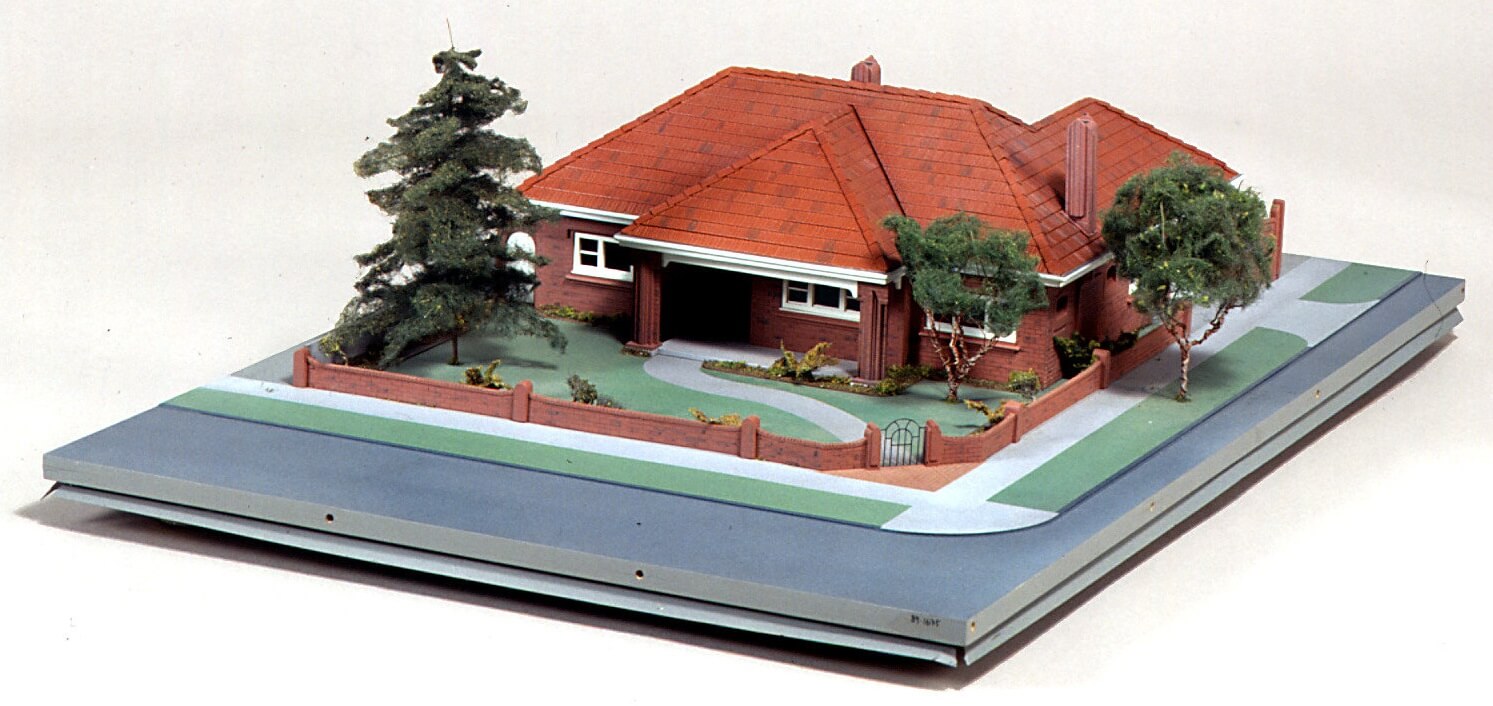

Model of D.C. Gallager House, Glenhuntly, Victoria. This house was designed by A.V. Jennings' first architect Edgar Gurney and built by E. F. Barnard in 1932. This model was made by Modeltech in 1989 for Museum Victoria's exhibition 'Home Sweet Home: Changes in Victorian Domestic Architecture, 1839-1989'. It is possible that Jennings himself lived at the house.

Image courtesy Museums Victoria.

Economic and Demographic Context

Population increase and affluence were the essential background to the expansion of the Jennings operation. In these four decades Australia experienced remarkable and largely sustained economic prosperity, apart from setbacks in the first half of the 1960s and in the mid-1970s. There were generally high levels of employment and a significant rise in real incomes. Prosperity resulted in rising living standards and expectations for most Australians. In essence, the Australian dream was to own a detached brick home on one’s own block of land and the affluence of the period enabled an increasing proportion of the population to do this. At its peak home ownership passed 70%.

Economic growth was stimulated and complemented by a rapid rise in population resulting from both domestic births (the post-war baby boom followed by those children starting their own families from the 1970s) and a large immigration program. The Australian population grew from about 8 million in 1950 to 10.3 million in 1960; then to 12.6 million in 1970, 14.7 million in 1980 and 17 million in 1990. All of these people needed homes.

Rising affluence also meant that most people could afford more of the belongings that could be purchased from the widening range of consumer items available in supermarkets, department stores and speciality shops in new shopping malls. Where once most people might possess just a few items of clothing and footwear, now they could fill drawers and wardrobes. More and larger couches, chairs, sideboards and heating appliances appeared in living areas. Where kitchens had held a few basic cooking and eating items, an ice chest and a small stove, now there would be more food in the cupboard or pantry, a greater range of crockery, cutlery and cooking utensils, a refrigerator and a smart gas or electric cooker. There would be at least one television in the home, a washing machine in the laundry and a parked car. On top of these were toys, sporting goods, transistor radios, word processors, books, etc, etc. To house all these belongings, people needed larger and appropriately-designed homes.

Jennings was available to build these.

Jennings’ Success

Jennings was at the forefront of transforming the average Australian home to satisfy rising incomes, higher expectations and to store accumulating belongings. At its centre the Jennings philosophy was to build places where people wanted to live and at an affordable price, and it undertook continuing research to establish what was wanted and how all this could be provided.

The number of homes built per annum by the company rose from 1808 in 1964 to 2000 in 1968-69; then 3000 in 1970-71 and 4493 in 1987-88 when Jennings was the market leader in every state, building nearly three times as many homes as its closest competitor.

Why was Jennings so successful?

Size and Design

One key to Jennings’ success was that the company was able to read both current expectations and future aspirations of that part of the Australian population in a position to buy a new home. Jennings developed a series of design formulae that catered to popular taste in the average Australian home, while providing value for money in construction.

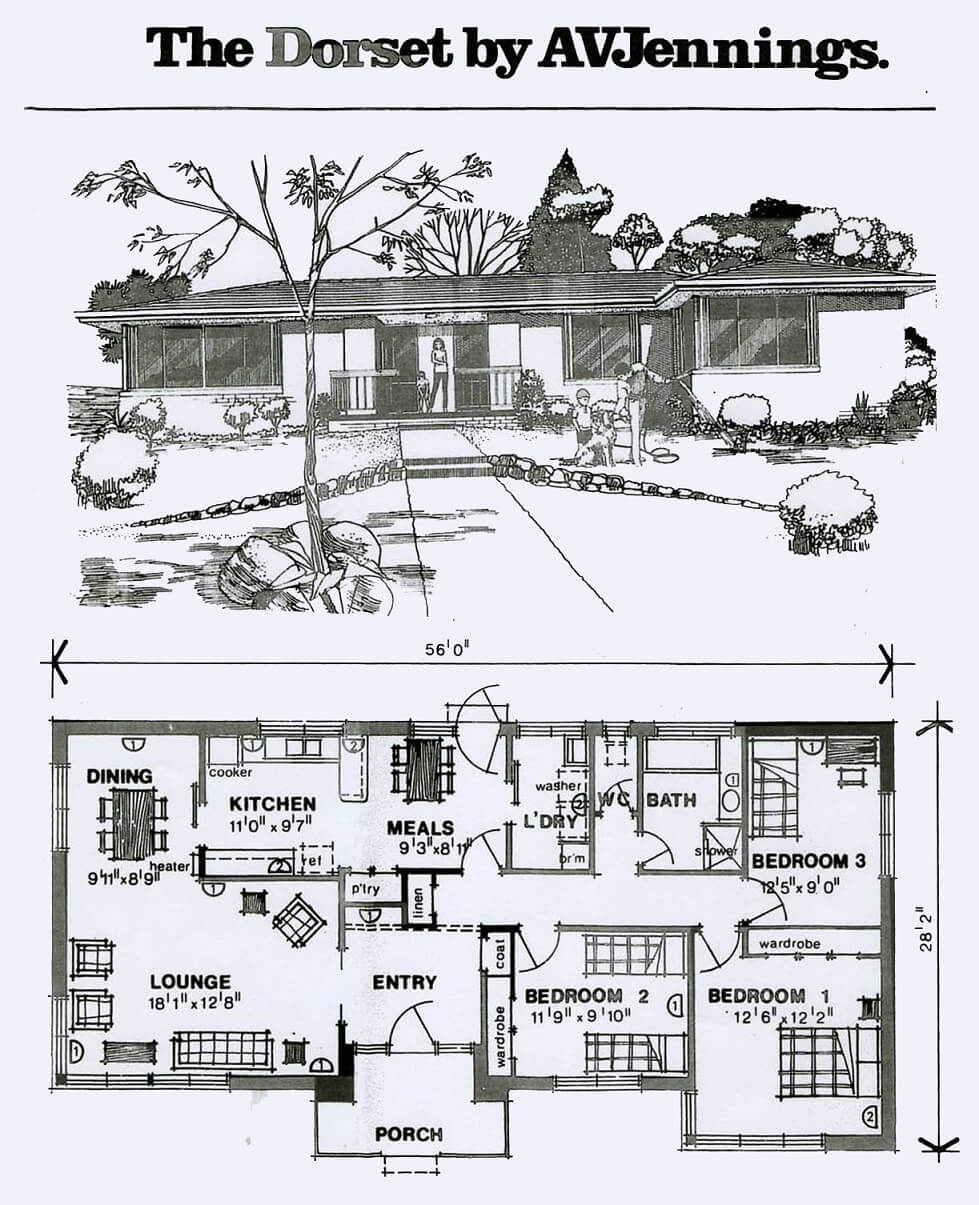

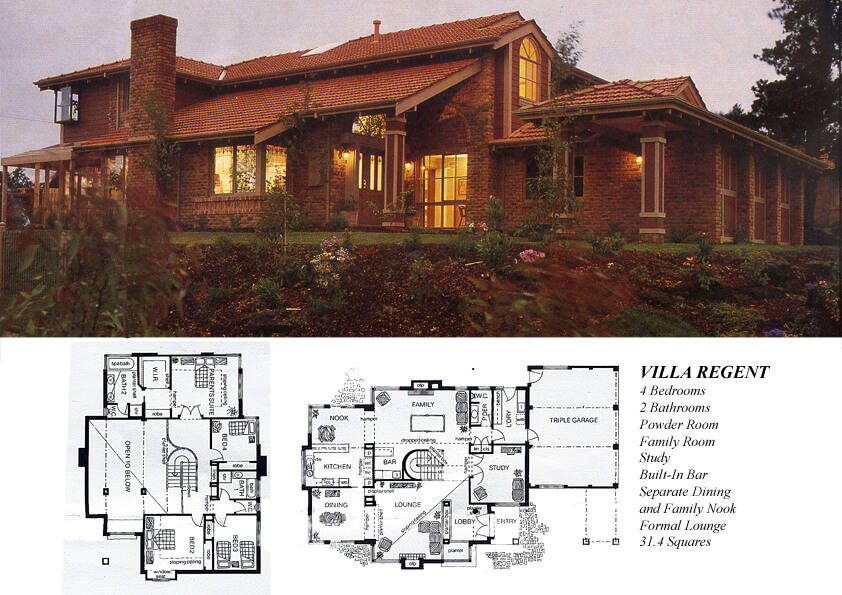

Perhaps the most dramatic change over the period was the increase in the size of the average new build, to provide the larger number of rooms that was expected and the space to keep all the occupants’ belongings. In the second half of the 1950s homes ranged from a little under to a little over 100 square metres. By the mid 1960s sizes were from about 110 to 125 square metres. Small homes remained about the same in the next two decades although during the Credit Squeeze of the early 1960s and the downturn of the mid-1970s there was a significant but temporary downsizing to provide a range of smaller affordable houses that were designed to offer as much modern facility as possible. By contrast, throughout the period the size of average homes increased to between 150 and 180 square metres. In the mid-1970s the largest homes were close to 220 square metres and in the 1980s a few reached about 350 square metres.

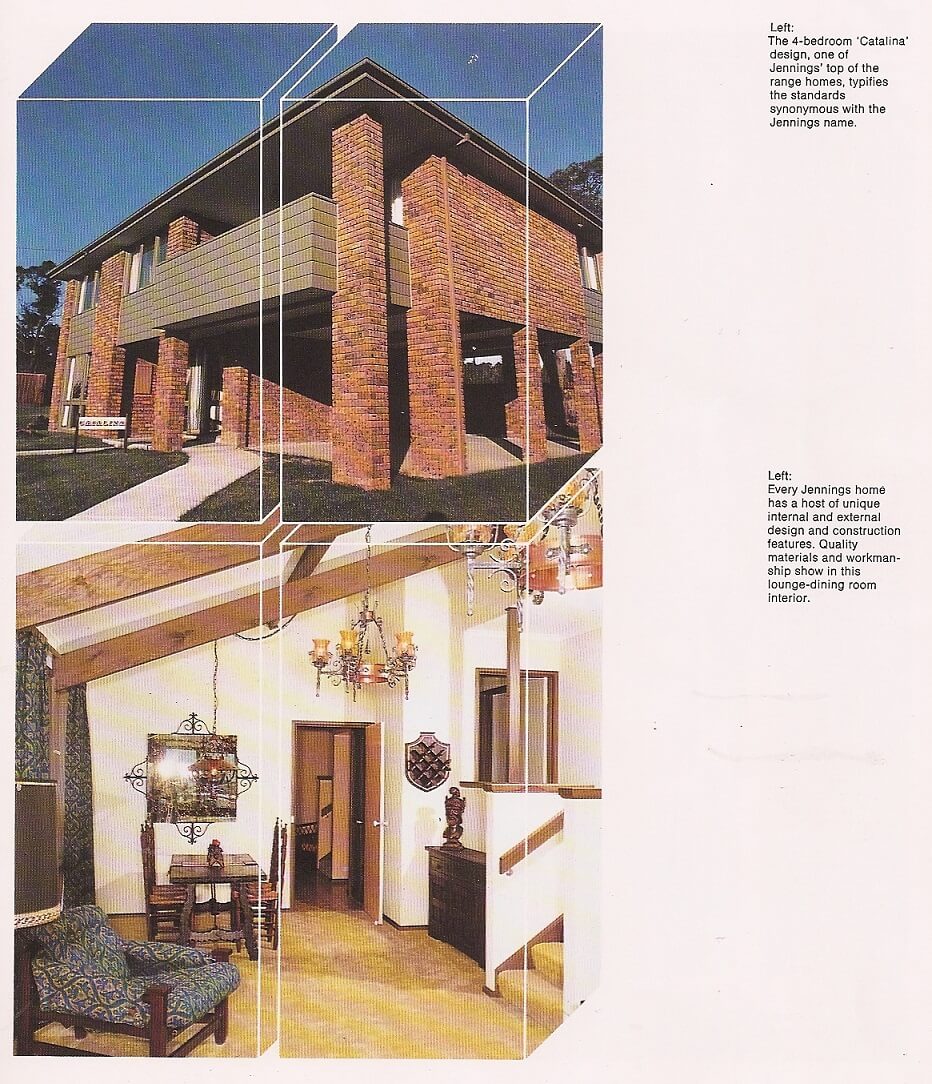

External appearance changed noticeably, evolving from essentially bland and utilitarian designs in the 1950s and early 1960s to significantly more imaginative and complex styles in later decades. Early in the period most Jennings’ homes were essentially a brick veneer rectangle, perhaps with a pitched roof running down the middle. Apart from a small weatherboard estate in Nunawading in 1956, Jennings built in brick veneer or in double brick where termites were a problem. From the early 1960s the double or triple-fronted cream brick veneer was very common, with a cement tiled roof. Over time there were increasing variations in house shape and roof styles, in a range of brick colours and with decorative features to provide variety.

Internal changes were dramatic. Community tastes, expectations and incomes enabled and demanded a much wider range of designs and fittings. Such was the revolution that a home built in the early ‘60s, that had been the height of luxury, was considered basic and old fashioned 25 years later.

The early 1960s home was likely to comprise two or three bedrooms, one bathroom, a living room, a dining area and a small entry hall. It was very basic with minimum fittings and no built-in cupboards. Toilets were often found in an outside structure together with the laundry. Over the period the number of bedrooms rose to a more typical four or even five and occasionally six, although one of these was likely to be more suited to a small office. Most bedrooms would have built-in wardrobes and the main bedroom could be equipped with a walk-in robe.

Sewered toilets were included inside the home and over time most homes featured an en suite bathroom adjacent to the master bedroom, as well as a well-equipped family bathroom and toilet. Fewer internal walls and a preference for open-plan living meant that the traditional lounge and dining rooms became less common. They were now likely to be replaced by a large family room and/or a rumpus room which was adjacent to the kitchen and open across a breakfast bar. In grander styles there might well be an additional formal lounge entertaining area and a dining room. Larger homes featured a substantial foyer rather than a small entrance hall.

The ‘split level’ home was another attractive innovation, although from the 1970s the more luxurious houses were likely to be two-storey with the bedrooms upstairs. There could also be a separate area for the master bedroom known as a parents’ retreat. To house residents’ numerous belongings, homes were increasingly designed with storage cupboards and other convenient spaces.

In the 1980s the company had about 60 designs available at any time, each with its own name. The practice of allocating names began in 1959 when the company changed from using a simple type number (eg Type 15) to distinguish between styles, to what was seen as a more attractive option. At first the names were random, such as the very popular early 1960s Glengarry. Subsequently many names were chosen beginning with A, B, C or D, to distinguish increasing size and cost, such as the Ascot, Bayside, Capri and Diplomat. Over time this approach drifted and naming again became less identifiable, such as the Millwood, Thornton and Penthouse in the 1980s.

Land size

Contributing to the trend towards double-storey homes was a decline in the size of the average block of land. As cities spread land became more expensive and this resulted in an ongoing trend to reduce the size of blocks. Up until the 1950s suburban Australians largely enjoyed a standard quarter-acre block with a 60-foot frontage, a decorative front garden and a vegetable and fruit garden in the back yard. From the 1950s the average block of land declined in size. By the 1970s a fifth of an acre was more common but was reduced even further in the following decades. This required much more imaginative design of estates to achieve most value from the land, and of the homes built on them.

One effect was to encourage construction of two-storey homes to reduce the footprint. Another, as blocks became narrower, was to design homes to run down the block rather than across. This necessitated a rethinking of room distribution, often providing different purpose zones between the front and the rear of the house. The entrance, and possibly living areas, would generally be closer to the street entrance. The increasing expectation that the average home would have an attached garage or carport also influenced the distribution of internal spaces and the way the home was placed on the block and entered.

All of this was seen as positive, apart from one aspect. Smaller blocks and larger homes reduced outdoor spaces for gardens and recreation. While there might still be a small lawn and planting at the front, there was less room for, or interest in, the traditional kitchen garden in the rear. From the air such suburbs were a sea of roofs cheek by jowl, with little space in between roof gutters. Privacy, gardening and even games of backyard cricket were more limited, but some homes still managed to squeeze in a small swimming pool – not built by Jennings.

‘Community Developments’ and Other Marketing

Jennings recognised that it was a marketing organisation as much as a home builder, and a great deal of time and resources were invested in researching what people wanted and how best to attract them to purchase a Jennings home. It was company policy to build on contract, not speculation, so all costs and conditions were factored in as far as possible.

While the company built a significant number of ‘OPOLs’ (On People’s Own Land), a large majority of its private homes were built on Jennings-owned land within a Jennings estate, or a ‘community development’ as they came to be known. Well-designed estates and homes provided efficiencies in scale and clever construction techniques, such as scheduling of tradesmen, offered value for money for both the company and home buyers.

Around each of Australia’s major cities Jennings bought up areas of land to develop when the time was right. Some were very large, notably the 250-hectare Karingal Community Development at Frankston in Victoria in the 1960s, although most were more modest. Other companies, of course did this, but seldom on the same scale, and they tended also to follow other trends that were substantially pioneered by Jennings in Australia. One of these was street layouts. Jennings’ developments were generally recognisable by their curving feeder streets and small private courts, to provide a mixture of visual appeal and privacy. Over time, however, this became the accepted design convention and was adopted by most companies.

Community developments provided a range of public assets to make them attractive places to live, including areas set aside for schools, shops, parklands and sporting facilities. Sir Albert Jennings, the founder, had included provision for such facilities in the estates he developed in the 1930s and that had proved very attractive.

One aspect for which Jennings is best remembered is its display villages. In each of its major developments a group of the latest model homes would be built, furnished, landscaped and opened the public. The idea was to show them as a home, not just a house. Display villages led to an unusual public phenomenon as a visit to them became a weekend ritual for many people, to admire, envy and observe the latest housing trends.

Allied with the display villages in the 1960s and into the 1970s was one of Jennings’ most remarkable marketing practices — the annual release of new design models with a great publicity fanfare. This was a conscious adoption of a similar marketing technique used by General Motors Holden to announce its annual release of modified or new models. However, designing and building the new display villages absorbed a large amount of company time and resources and when economic conditions deteriorated in the 1970s it was decided to abandon such a high-pressure activity for a more leisurely release of new designs. As a market innovator Jennings adopted many other practices to encourage the public to visit their community developments where they would be met by salespeople offering to show the latest design models, offer advice and to provide finance.

AV Jennings had an extraordinary run as the nation’s home builder and most of us can be pretty sure that we know someone who lives, or has lived, in an AV Jennings home.

Author: Don Garden

Further reading:

Don Garden Builders to the Nation: the A.V. Jennings Story. Melbourne University Press, 1992

Roy Edwards & Vic Jennings with Don Garden AV Jennings: Home Builders to the Nation. Arcadia, 2013