For most of human history the survival of infants depended on breastfeeding, most often by their mothers, but sometimes by another lactating woman. Although vessels to enable hand feeding existed from ancient times, the death rate of infants fed with them was high. It was not until the twentieth century that glass feeding bottles and special infant formula made the hand feeding of infants safer. The rate of breastfeeding also declined over this period, although it remains the recommended method of feeding young babies.

Maternal breastfeeding

Most women who gave birth in nineteenth-century Victoria expected to breastfeed their infants. It was well-known that artificially fed babies often died. Indeed, there was one such instance in my own family. My great-great grandfather Joseph Elliott emigrated to Adelaide in 1850, aged just sixteen. Within a year he was married to a young woman he met on board ship (giving his age as 20!) and shortly afterwards travelled briefly to the Victorian gold fields. He returned quite quickly because his wife Elizabeth was pregnant. Tragically Elizabeth died shortly after giving birth to their son (also Joseph), and at the ripe old (actual) age of 18 Joseph senior found himself a widower with an infant son. Although young Joseph survived the loss of his mother, he did not thrive, and died eight months later. Joseph subsequently married his first wife’s friend (Rebecca) and together they had nine children, seven of whom survived. Joseph was the author of a remarkable letter to his mother, published a century later as Our Home in Australia.

So far as we know, Rebecca Elliott breastfed all her children, but then, as now, not all mothers could breastfeed successfully and there was a steady demand throughout the century for wet nurses, lactating women who were prepared to feed other infants. Almost all wet nurses were poor women, often women whose own children had died, or who were given to others to hand feed, but there were also nurses with an abundance of milk who managed to feed both their own and another baby successfully. Generally wet nurses lived in with the family, for obvious reasons. However since wet nurses had to be paid, those who employed them were generally the more prosperous families in any past society.

In earlier centuries the use of wet nurses was very common amongst élite women who wished to be spared the inconvenience of suckling infants, but this seems to have been rare in Australia. There was also an ongoing debate about the advisability of employing wet nurses, since some were the mothers of illegitimate children. Speculation was rife at times that ‘moral contagion’ might be passed to the infant through the milk, although this theory had less credence by the nineteenth century. However, we do know from stories like that of Maggie Heffernan, that finding employment as a wet nurse was one option for the mothers of illegitimate babies. Maggie gave birth to an illegitimate son in late December 1899. Three weeks later, penniless and exhausted, she drowned him in the Yarra, but then almost immediately found employment as a wet nurse with a family in Hawthorn. It seems that families in need of nurses often contacted the Women’s Hospital, where many poor women gave birth. Maggie herself had been transferred to the Women’s Hospital immediately after the birth of her son and she returned there seeking a position as a nurse. In Maggie’s case this was a short-lived placement, as she was arrested shortly afterwards. The story is a tragic one, not only for Maggie herself and her little boy, but also for the Hawthorn infant who was suddenly deprived of breastmilk. The family must have been frantic.

Wet nurses were also in demand in orphanages, where they were crucial to the survival of newborn infants. Many notes of inquests record the sad death of poor and illegitimate children who were put out to ‘dry nurse’ or hand feed, while their mothers sought employment, sometimes as wet nurses.

‘Bad breasts’

Breast feeding may be natural, but it carries its own hazards for the mother. Cracked nipples, blocked milk ducts and resulting breast infections are all painful conditions that require swift medical intervention. Many of these are now treated quickly and efficiently, often with antibiotics, but treatment before this was slow and painful. Women with infections often had to endure weeks of extreme pain until an abscess formed and could be drained. They were left with scarring that could impede future feeding, especially when scarring was on or near the nipple. Many patent remedies claimed to be able to cure ‘bad breasts’ as they were called. The ubiquitous Holloways pills and ointments was one brand that advertised along these lines, but almost certainly it had little effect.

Early bottles

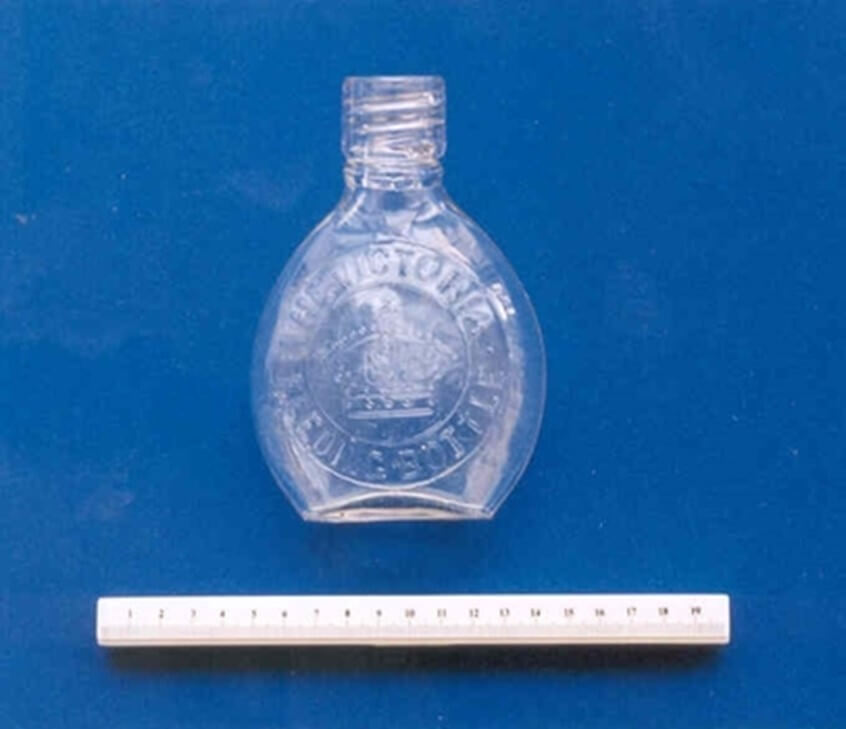

Women who were unable to feed their infants themselves and who could not afford to pay for a wet nurse, naturally looked for some means of artificial feeding. Containers made of wood, horn, ceramic and pewter were all used, usually with cork, sponge or leather nipples to allow the infant to suck, but these were very difficult to clean. Glass bottles were produced from the mid-nineteenth century and these were much easier to keep clean, but the problem area was still the artificial nipple. One popular glass bottle used a long tube with a nipple attached. It was popular because it allowed an infant to feed itself. But it was almost impossible to clean the tube and nipple effectively and eventually it earned the nickname the ‘murder bottle’. Of course, the problem was compounded by the fact that germ theory was not widely understood until the mid-nineteenth century, (or later in the general population) and there was no understanding of the need for infants’ bottles and teats to be sterilized.

Baby feeding from a bottle with tube attached, c.1895

Reproduced courtesy Museums Victoria

Later in the nineteenth century bottles were made in a ‘banana’ shape, with the teat attached directly to the glass and the flow regulated by a valve at the other end. These were safer to use. They also began to feature measuring marks on the glass, to indicate how much milk the child was receiving, reflecting new ‘scientific’ ideas about infant feeding and infant care.

Finding an appropriate material for the nipple or teat continued to be problematic. Rubber was used from the mid-nineteenth century, but at first it was stiff and had an unpleasant taste. It was not until the early-twentieth century that a suitable heat-resistant form of rubber was developed that could be moulded to shape.

Artificial milk

Animal milk was the most common artificial food offered to hand-fed babies, but sourcing clean, fresh milk was not always easy, especially in the city. Although there were many small dairies supplying milk in Melbourne, there was little oversight of the quality of the milk and adulteration at the point of sale was also common. Refrigeration was gradually introduced to the dairy industry from the 1880s, but at first it was limited to the larger suppliers. Small herds were still being milked by hand and the milk stored without refrigeration until well into the twentieth century. Australia was also slow to adopt sterilisation practices and it was not until the 1950s that most milk sold was pasteurised. Many families struggled to keep milk fresh at home too. Iceboxes were common in middle-class families from the mid-nineteenth century, but poor families could not afford the regular ice deliveries needed to keep food cold. Household refrigerators were often at the top of the family wish list for appliances but were not widespread until the 1950s.

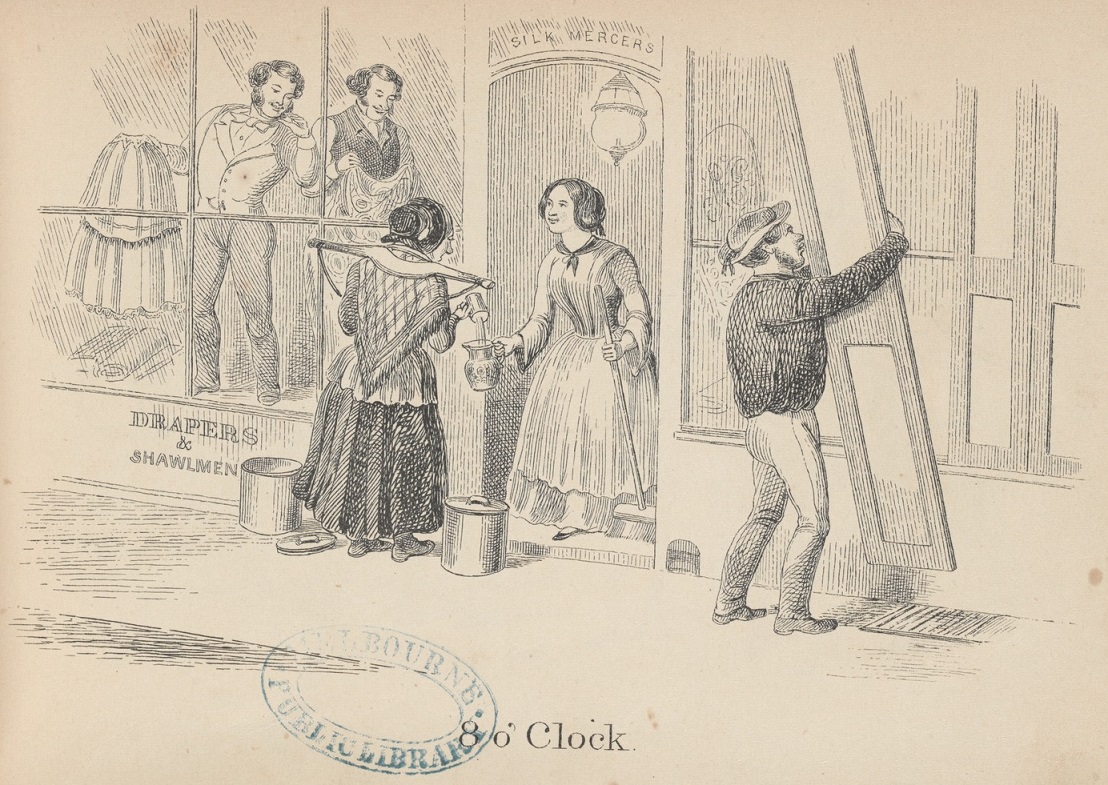

Dairywoman delivering milk, in ‘8 o’Clock’, by Henry Heath Glover, lithographer, 1857

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

At first milk was sold door-to-door from large pails or tins. Buying early in the morning helped to ensure that it was fresh.

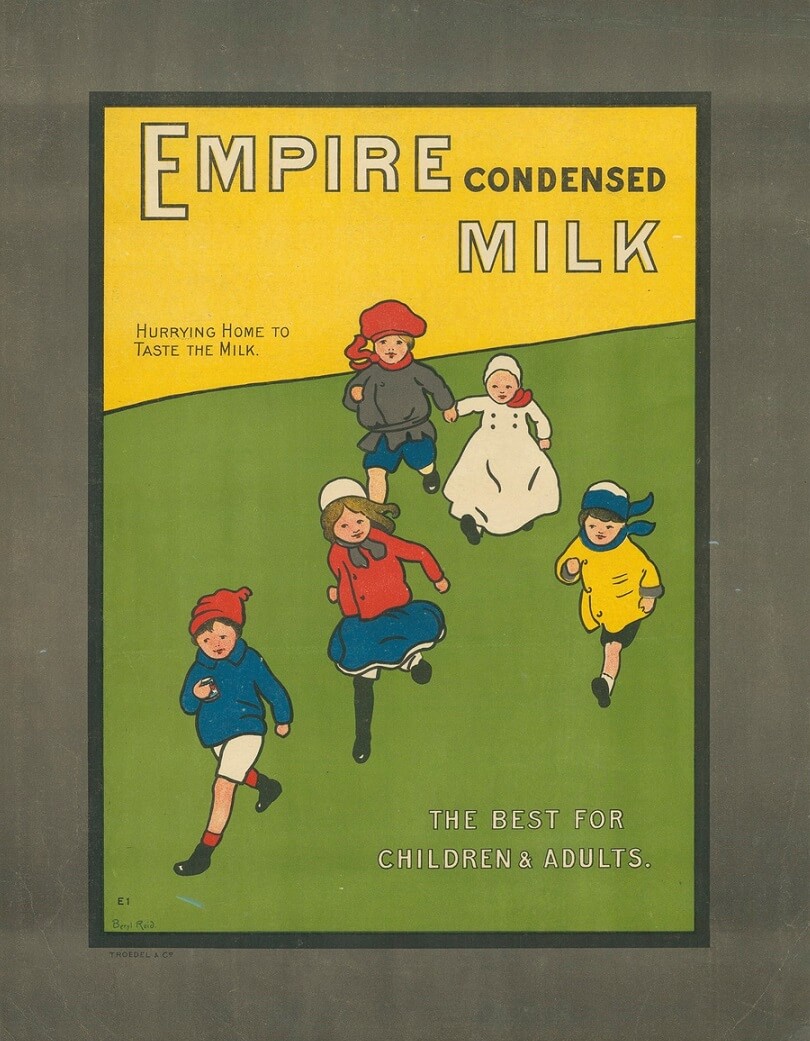

Not surprisingly many families turned to an alternative form of milk to feed their infants — condensed milk. Condensed milk, cow’s milk from which much of the water had been removed, was first developed in the 1850s, but was not marketed successfully until later in the century. The inclusion of condensed milk in soldiers’ rations during the American Civil War helped to popularise it. Condensed milk was commonly sold sweetened and was sealed in tins. In this form it could be stored without refrigeration for years, making it very useful for families without iceboxes. By the 1880s thousands of tins were being imported each year into Victoria and the Victorian Government debated increasing the import tariff to try to stimulate a Victorian industry. Local doctors campaigned against each attempt, arguing that such a tax would impact unfairly on the poor, who, they argued, depended on condensed milk to feed their babies. (Australasian, 22 September 1883, p.25) In 1911 Nestlé built a huge manufacturing plant near Warrnambool, effectively ending the debate. In the meantime, Blainey argues that many families preferred condensed milk to fresh, believing it to be free of the contaminants that soured fresh milk. It was left to later generations to point out the damage caused to infant teeth by a diet of sweetened condensed milk, but in the meantime, it may well have kept poor babies alive. An unsweetened version of condensed milk, marketed as evaporated milk, was produced from the 1880s, and by the 1930s was preferred by paediatricians to condensed milk, but by then the popularity of condensed milk was assured.

Infant formula

By the late-nineteenth century products marketed specifically as infant formulae were also appearing. They came in powdered form, to be mixed with either water or milk. At first many of these infant foods lacked essential nutrients, including vitamins (first identified in 1912) and iron. These were later added, and gradually infant formula improved as the science behind infant metabolism progressed. Unfortunately breastfeeding declined in response to the aggressive marketing of infant formula. It was not until the 1970s that breastfeeding rates began to climb once again, as movements to promote breastfeeding expanded. However, there can be no doubt that the availability of safe infant preparations saved the lives of many babies whose mothers were unable to breastfeed.

Advertisement for Lactogen infant formula

Australian Women’s Weekly, 27 December 1947

Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia

‘Scientific’ mothering

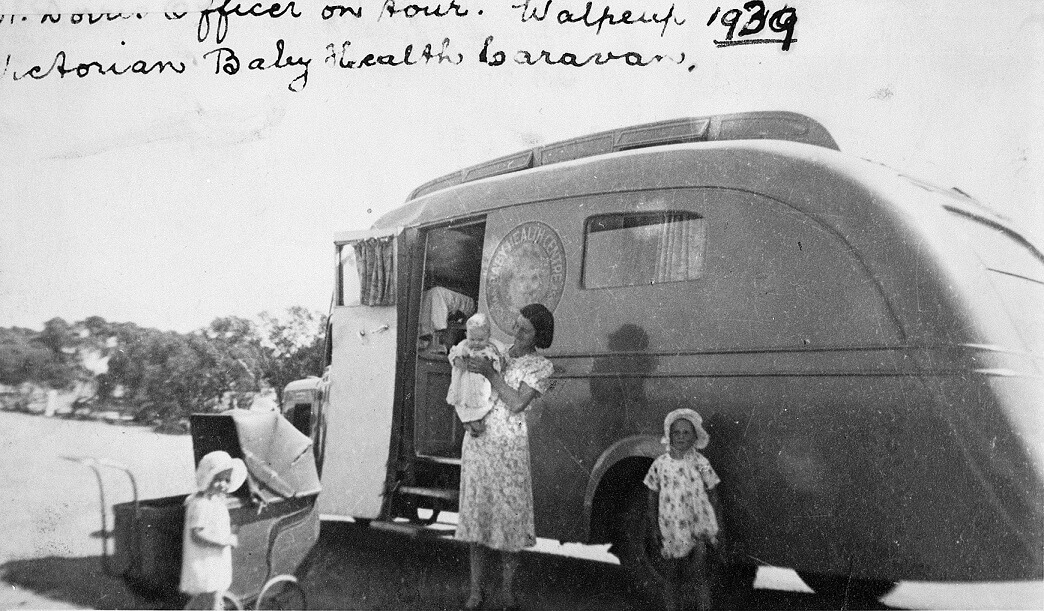

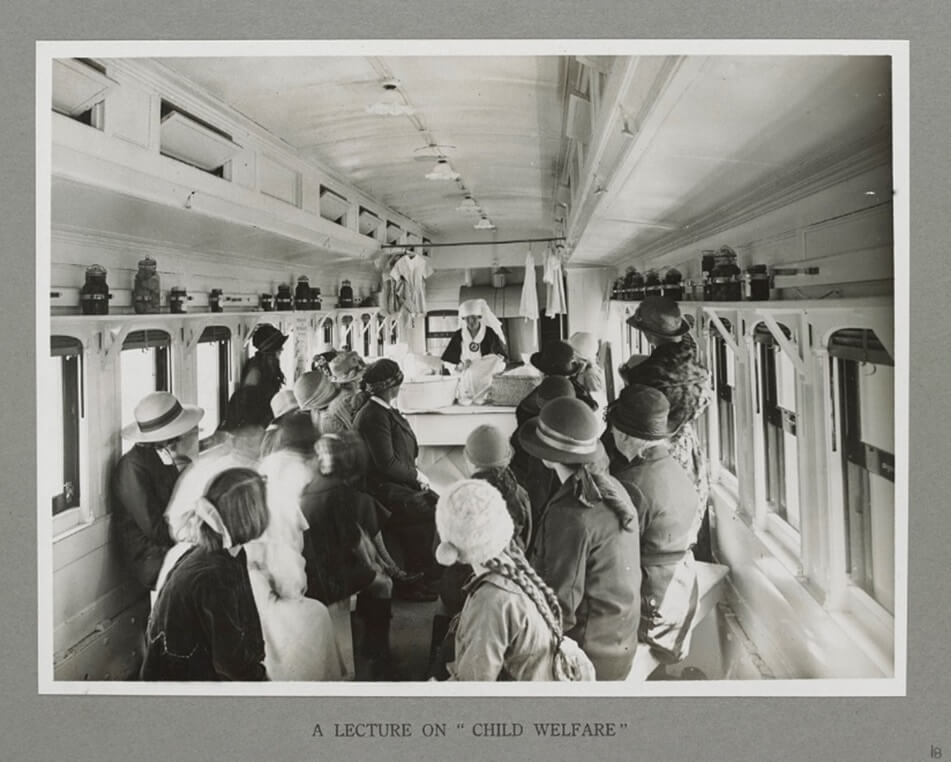

Quite apart from the apparent convenience of bottle feeding, some mothers were persuaded to adopt it because they could see clearly how much milk their baby was drinking. Ironically, some of the insecurity around breastfeeding may have followed the spread of baby health clinics, which dispensed advice about the ‘scientific’ care and feeding of infants. The infant health movement was an official response to what some regarded as the alarming fall in the birth rate, which was apparent throughout Australia by the 1890s. Dr Helen Mayo established the first ‘School for Mothers’ in Victoria in 1909, but it was not until late in the First World War that the infant welfare movement really expanded. At first the emphasis was on instructing the mothers of the poor and the first clinics were established in inner-city suburbs like Richmond, North Melbourne, Carlton, South and Port Melbourne, Fitzroy and Collingwood (all 1917-18). But Baby Health Centres soon expanded throughout Melbourne and in regional Victoria. Kereen Reiger points out that patronage of the clinics grew from 913 in 1917, to 750,000 by 1938. (p.133) The Victorian Railways came to the party in rural Australia with an infant care carriage on the Better Farming Train. Classes of rural schoolgirls were taken to visit, along with local mothers.

The public response to the Better Farming Train, and to the mothercraft section in particular, was reputed to be very enthusiastic. As the West Gippsland Gazette reported:

It is just here that the lessons given by Sister Peck, of the Baby Health Centre, are seen to be of even national importance, for the babies of to-day are the progenitors of the future generation. A baby properly fed and nourished, grows up to be a national asset, while another, fed on improper diet through ignorance, on the part of a young mother, is liable to be handicapped in the race of life. Not only in the feeding, but in clothing, the making of suitable clothes, and the general care of the baby, valuable information was imparted, which is calculated to have an important effect, in the aggregate, on the infant mortality of the State. … Because of the value of the information imparted, especially to young women, this department of the train should be welcomed everywhere, as indeed it is.

- West Gippsland Gazette 21 April 1923, p.3

While much of the information was indeed helpful, especially the emphasis on hygiene, other instruction on infant feeding was possibly less so. In the period after the First World War and for decades afterwards, the Infant Welfare movement was strongly influenced by the teachings of a New Zealand doctor (later Sir) Frederic Truby King. Truby King was a great believer in regular feeding schedules, of 3-4 hours, and in weight gain according to a set matrix. The ‘old’ methods of breastfeeding ‘on demand’ were disparaged. Unfortunately, that probably undermined the establishment of successful breastfeeding, which often works best on a ‘little and often’ or ‘on demand’ schedule. Many a post-war mother (my own mother amongst them) remembered sitting agonised, listening to her baby scream, and watching the clock until the requisite four hours was up, and she could legitimately offer the feed. Mothers also worried about whether their babies were getting ‘enough’ milk, as judged by the schedules given by the infant health nurses. Bottle feeding took away the guess work. Even in my own time, I remember being given directly contradictory advice on two successive visits to a baby clinic in the early 1980s. On one visit I was told that my daughter had not gained enough weight and that I should offer a supplementary bottle of formula. On the second, after she had gained ‘too much’ weight, it was suggested that I should cut out a feed. Thankfully, I was secure enough by then to see the humour in the situation and just kept ploughing on. Meanwhile, while many mothers made a valiant attempt to breast-feed their infants for the minimum recommended period of three months, the drop-off rate after this point was high.

Breast is best

From time-to-time paediatricians and Infant Health professionals made a concerted effort to promote breastfeeding, as ‘best for baby’. There was particular concern about the decline in breastfeeding amongst First Nations women, especially those in remote locations without access to good quality water. The poster shown below was circulated to promote breastfeeding in Indigenous communities.

Sharing the load

One great advantage of bottle feeding of course, is that both parents can share in the load (or the delights), and as many more women returned to work after birth, some form of bottle feeding was often essential. Thankfully, preparing and transporting bottles is now much easier, as the bottles themselves are much lighter than the old glass ones. Indeed, the next leap forward in bottle technology was probably the advent of polypropylene, a form of plastic with high heat resistance. Such plastic bottles have now replaced the use of glass infant feeding bottles entirely. They are light, easily sterilized, but more importantly, do not break when older babies drop them, or throw them out of their cots. This was a recurring hazard for glass feeding bottles!

To conclude — in Victoria’s early colonial years breastfeeding was essential to an infant’s survival chances. While hand-reared infants did survive, they often struggled to thrive, not least because they received none of the immunity provided in the first months from the mother’s milk. Where a mother was unable to feed, the assistance of a wet nurse was the preferred alternative, but most could not afford to pay for a nurse. Infant feeding vessels gradually improved during the nineteenth century, along with an awareness of the need for high standards of cleanliness, but it was not really until the early-twentieth century, with the advent of improved glass bottles and special infant formula, that the survival of bottle-fed infants was more assured. Breastfeeding rates declined in proportion. However, from the 1970s breastfeeding rates began to climb again, and in 2022 over 90 per cent of infants had received some breast milk. Nevertheless, the infant feeding bottle is still an essential object in most contemporary families where there are infants.

Sources and further reading

Rima D. Apple Mothers and Medicine: A Social History of Infant Feeding 1890-1950. University of Wisconsin Press, 1987

Australian Bureau of Statistics Breastfeeding 2022.

Valerie Fildes Breasts, bottles and babies: A history of infant feeding. Edinburgh University Press, 1986

Bryan Gandevia Tears Often Shed: Child health and Welfare in Australia from 1788. Sydney, Pergamon, 1978

Milton Lewis, ‘The Problem of Infant Feeding: The Australian Experience from the Mid-Nineteenth Century to the 1920s’, Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences, Vol XXXV, Issue 2, April 1980, pp. 174-87

Felicity Nowell-Smith, ‘Feeding the Nineteenth Century Baby: Implications for Museum Collections’, Material Culture Review, Vol. 21, Spring 1985, pp. 15-23.

Pat Quiggan No Rising Generation: Women & Fertility in Late Nineteenth Century Australia. Canberra, Australian National University, 1988

Kereen Reiger The disenchantment of the home: Modernizing the Australian family 1880-1940. Melbourne University Press, 1985

Ian G Wilkes A History of Infant Feeding: Part IV – Nineteenth Century. 1953