Many families keep traditions — ritualised occasions or practices, created through repetition, often across generations. Some are unique to them: others part of a wider communal identity, but all express meaning for that family, helping to define it, and in some way distinguish it, from any other. They might be special occasions, observed at specific times in particular ways; or foods from a distant homeland, passed on to new generations. Some link present generations to ancient practices, seeking to preserve both identity and knowledge. Others may be ‘new’ traditions, invented by families over a lifetime. But all have special meaning for family members.

Most ‘traditions’ claim a basis in some historic past, whether ‘real’ or invented. In their wonderfully provocative book of essays on The Invention of Tradition (first published in 1983 and still in print), Eric Hobsbawm and Terence Ranger focused mainly on the traditions invented in the post-industrial era to express state or nationhood, or, for example, to imbue the pomp and circumstance of British monarchy with its aura of antiquity. But in the Belongings exhibition our focus was domestic. We were interested in the traditions preserved or invented in families, and we found a wonderfully-diverse range of activities.

Foodways

Food and cooking are often at the heart of family traditions. We see it expressed most clearly in culturally diverse families, where food becomes a tangible link with a homeland. Along with language, food and its associated ceremonial rituals are powerful ingredients in preserving cultural identity. Sometimes these food cultures are expressed through specific objects, either brought from ‘home’ at the time of migration or imported later. When Emanuela Nigro and Vencenzo Candela migrated to Victoria in the 1920s they brought a tomato paste maker along with them, to ensure that they could continue to make the all-important tomato passata at home. They also either brought a coffee roaster with them or imported one soon after arrival from a mail-order catalogue, so that they could continue to enjoy coffee made with roasted and freshly-ground beans. Melbourne in the 1920s had no cafes to supply such coffee. These objects were later donated to Museums Victoria and are shown in the Belongings exhibition.

Tomato paste maker, c. 1920s

Museums Victoria

Coffee roaster, c. 1920s

Museums Victoria

Used by the Candela family who immigrated to Victoria from Italy in the 1920s. Either brought with them or purchased from mail-order catalogue after they arrived.

The Candelas made much of their own food, including pasta, tomato paste, wine and sausages, using recipes and techniques from their home country. The recipes were passed on to their children, although the objects were eventually replaced with new.

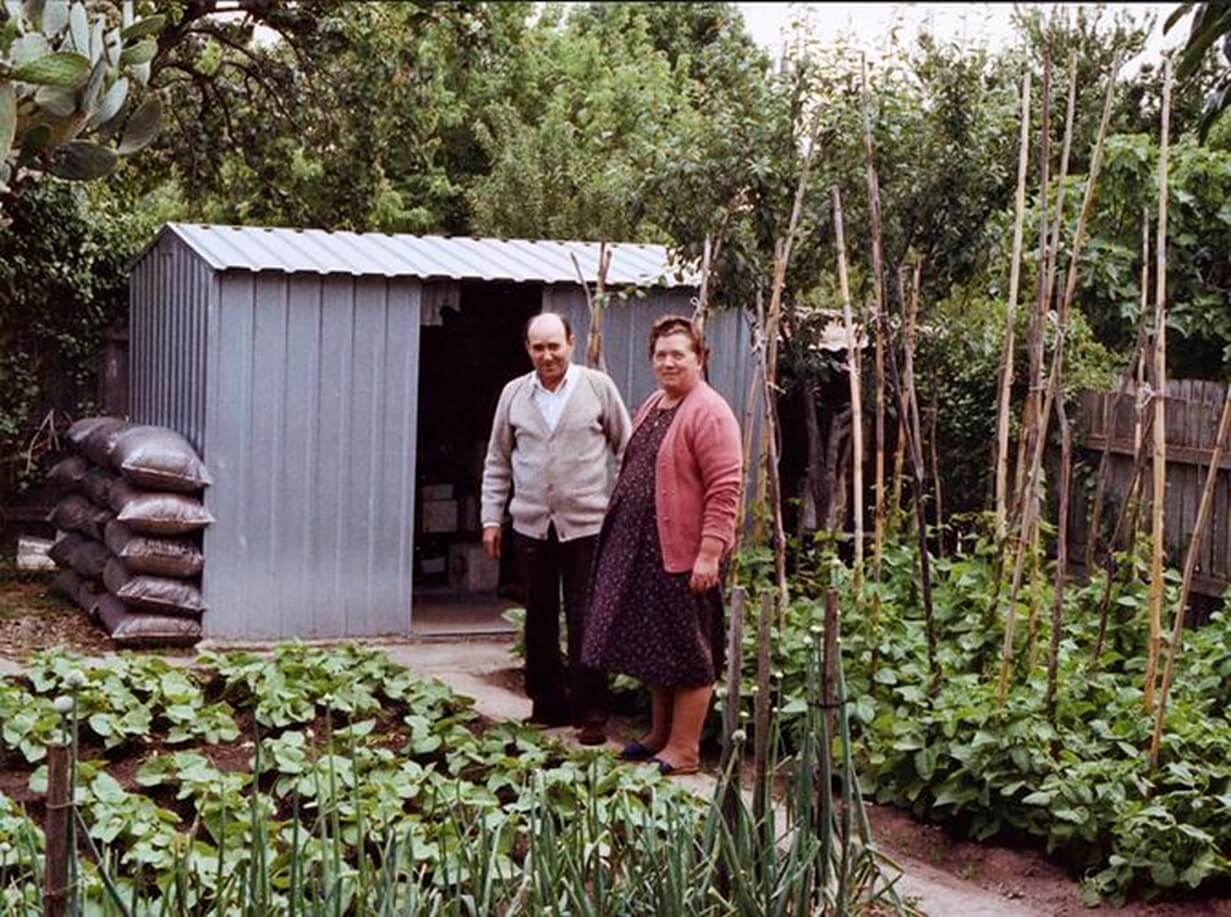

Domenico and Domenica Annetta in their backyard, Reservoir, 1994.

Reproduced courtesy Museums Victoria. Copyright Bruno Annetta.

Those who had been gardeners at home brought their skills with them and many established flourishing food gardens in Victoria. Domenico and Domenica Annetta had been farmers in Calabria and established vegetable gardens in their various homes in Victoria. After immigrating in 1960 Domenico drove a delivery van for his brother, who was a baker in Port Melbourne. Their first home was in Lyall Street Brunswick, but by 1984 they had moved to Reservoir, where this photograph was taken. The 1994 photograph above shows the transformation wrought in the backyard garden over the decade.

Domenico & Domenica Annetta in their backyard Reservoir, c. 1984.

Reproduced courtesy Museums Victoria. Copyright Bruno Annetta.

Domenico later made a series of miniature models of farming implements to teach his children and grandchildren about his farming life in Calabria. These are preserved in the collection of Museums Victoria.

Many other families found ways to continue making and preserving favourite foods in their adopted country. Inevitably, methods evolved to suit new conditions, but techniques and recipes were often preserved. German families, who settled in parts of Victoria in the nineteenth century, continued to make their sausages, sometimes in backyard ‘kitchens’. This was often a family affair, as this photograph of the Hoffman family, taken in about 1900 suggests. The photograph shows a mincing machine, large mixing pail, Mrs Hoffman with the sausage skins, and a sausage maker, worked by turning a handle.

Hoffman family making German sausage, Glenore District, c. 1900

Reproduced courtesy Museums Victoria

When other groups migrated to Victoria after World War II they brought their food preferences with them. The Kucan family came to Victoria as displaced persons in 1949. Although they had spent four years in a refugee camp in Austria, they came originally from Ukraine. After working their required period for the government, Ivan Kucan and five friends came to Melbourne looking for land to build homes. They bought land in the same street in Newport and helped each other to build their homes. Ivan had been a butcher in Ukraine, and he made a domestic smoking machine to smoke hams and sausages in the traditional way. Photographs record the process with his neighbours helping. You can view some of these in the collection of Museums Victoria.

As the Victorian population became increasingly diverse in the late-twentieth century, many new foodways were introduced to Victorians. It was often important for members of those communities to meet over familiar food, especially as individual community members aged. The Vietnamese and Indo-Chinese Elders Group is one such group. Formed in 1987, it has met fortnightly since, to socialise and prepare a meal together. Such gatherings help to combat loneliness and to forge connections in a new society.

Family favourites

Many families have favourite recipes, some of which have been passed down through the generations, even as food fashions change. I still have my mother’s recipe for tomato sauce, which calls for 36 pounds (a bit over 16kg) of tomatoes. She used to make it in a huge pot on top of the stove, using newspapers as an improvised lid, and the rich smell would linger in the house for days (it uses a lot of garlic). The recipe was hand-written in her recipe book, date unknown, but both she and her older sister used the same recipe. It was almost certainly older than either of them. This recipe is still a family favourite, passed down to our children in turn, though we no longer make it in such generous quantities! We also preserve the family recipe for tomato chutney, along with various favourite recipes for cakes and desserts. One particular ‘pudding’ (a vanilla pudding with a self-saucing chocolate sauce,) is still requested for various birthday dinners, now by a third generation.

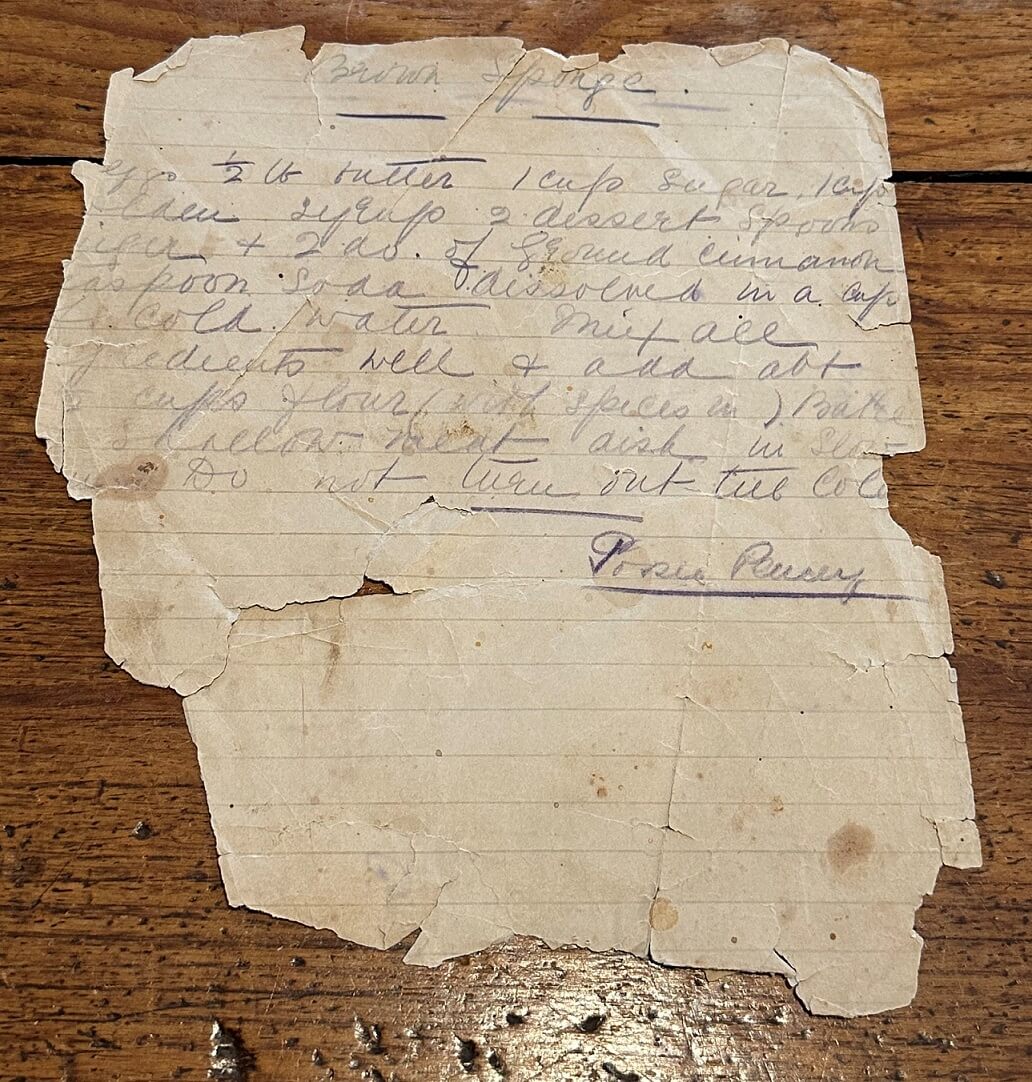

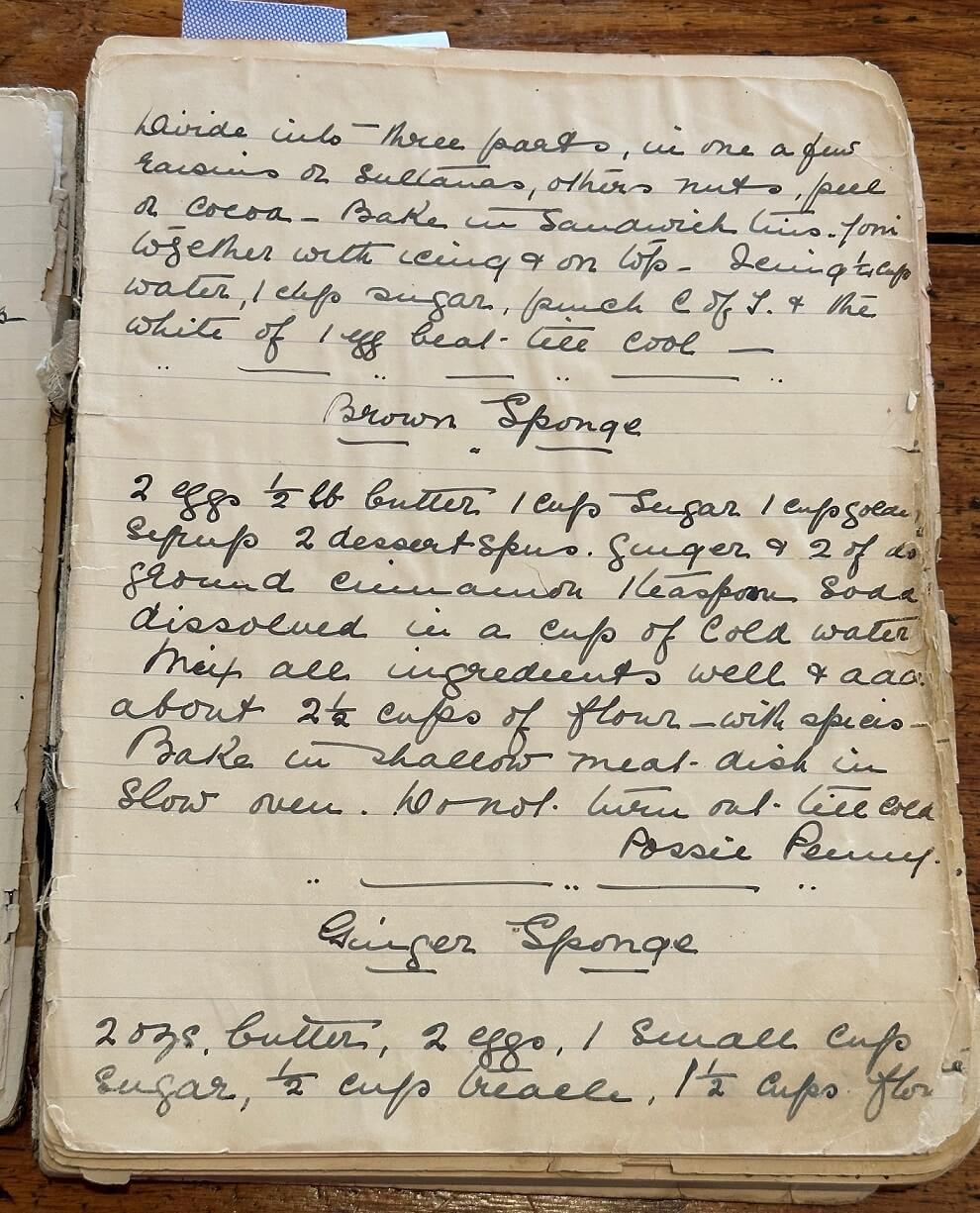

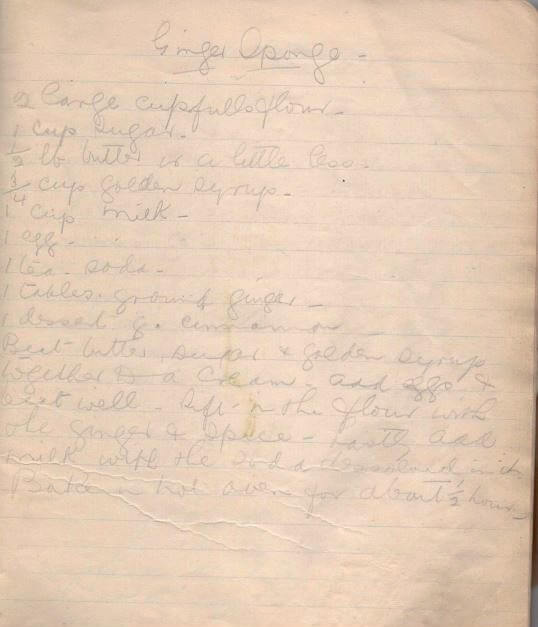

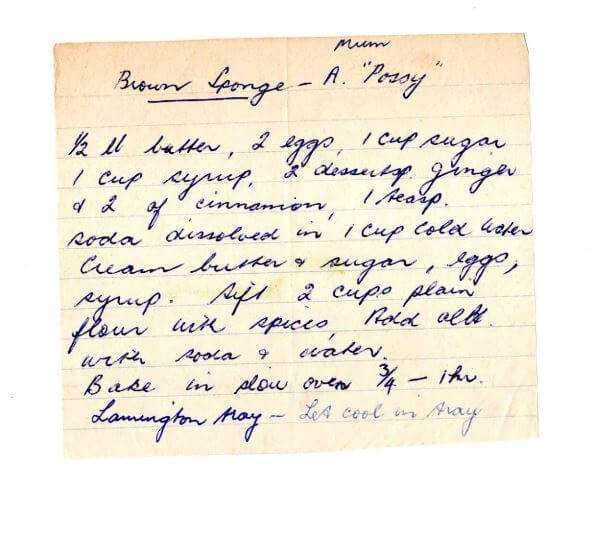

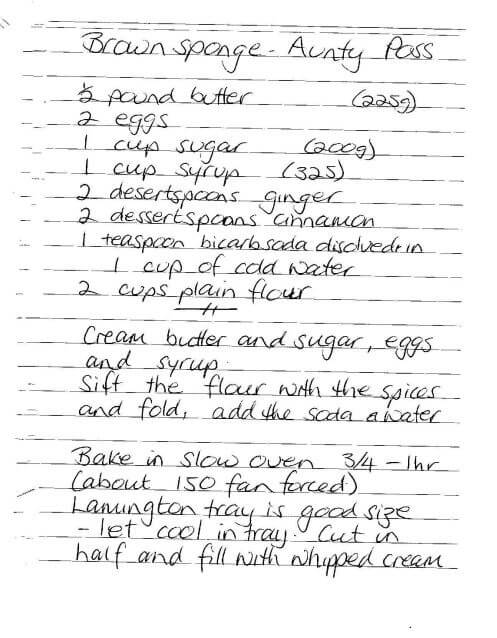

In the Belongings exhibition we featured several recipe books, handed down in families and preserved. One family favourite was a recipe for a ‘brown sponge’, also known as ‘Aunt Poss’ (or Possy’s) brown sponge’. This was a ginger sponge, first baked by Rebecca Reid (born 1862), and passed on to her daughter Beatrice Janet Mallon and her grand-daughter Dulcie Elaine Maxwell. Dulcie and her daughter Helen Mitchell still bake the sponge today. The recipe has been translated from imperial to metric measurements and modified for modern appliances.

Recipe for ‘Brown sponge’ exhibited in the Belongings exhibition 2024

Reproduced courtesy Dulcie Elaine Maxwell

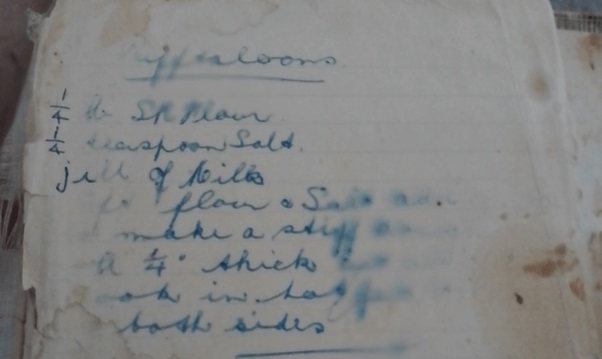

Other favourite recipes came to light once the Belongings exhibition opened. We explore the history of the Salau teapot elsewhere in this online exhibition. This story also introduced us to ‘puftaloons’, little cakes made from a mixture that resembled damper, but eaten with jam and cream. They were baked on a griddle iron, rather like Welsh cakes, and were also known as ‘johnnycakes’. These were a firm favourite of the Salau family and their descendants after the Second World War, though they are now almost unknown. We reproduce the recipe here:

Lena Salau’s puftaloons

¼ lb (pound) SR (self-raising) Flour

¼ teaspoon Salt

Jill (one gill) of Milk

Sift flour & salt, add milk and make a stiff dough.

Pat or roll out to about ¼ inch (6mm) thick, [cut out rounds] and bake on a hot pan on both sides. Serve buttered or with jam & cream.

Family celebrations

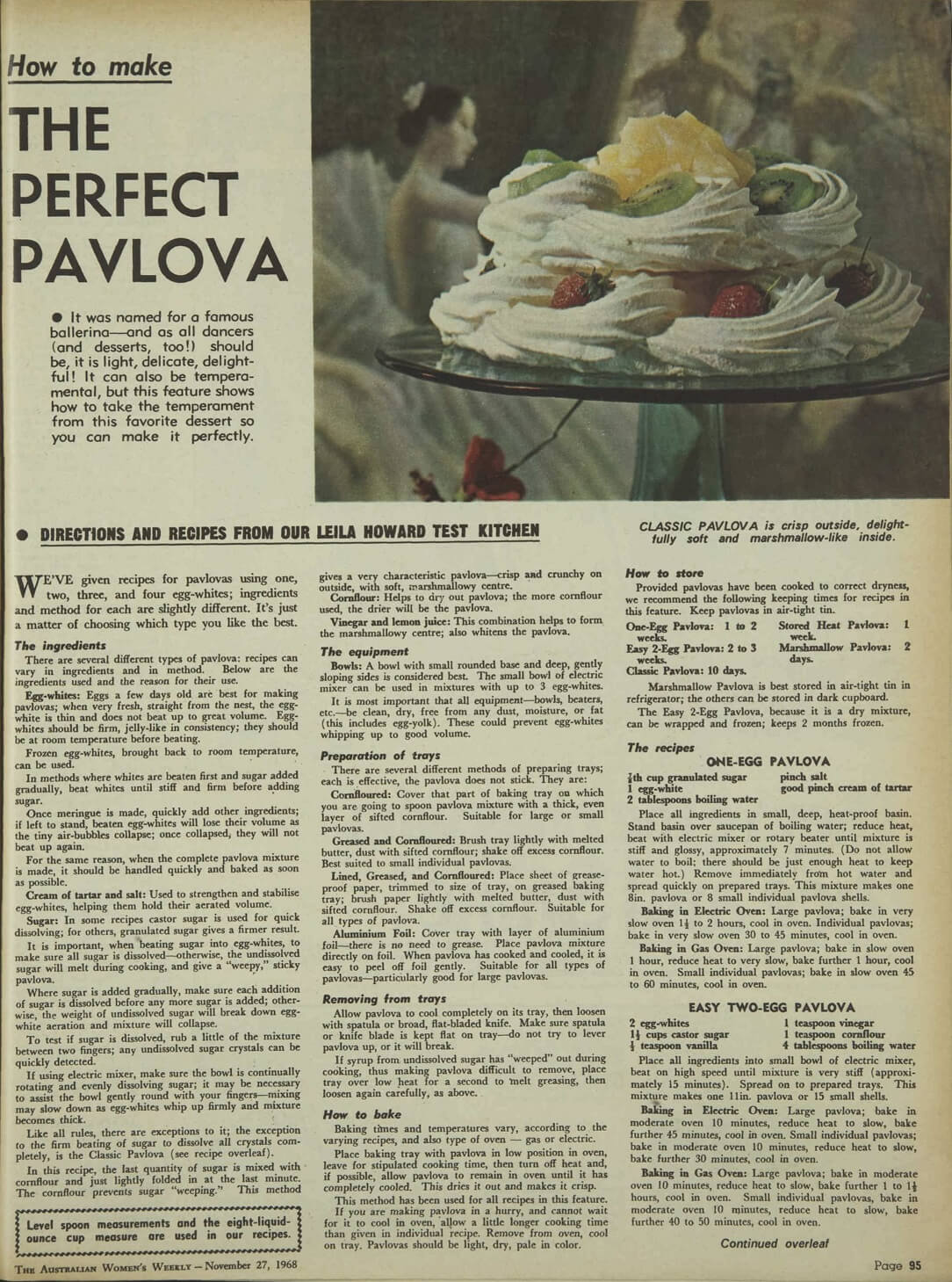

The celebrations observed in families often develop a sense of tradition. Many observe popular religious festivals — Christmas, Easter and Passover, or more recently Ramadan and Diwali — with special food served to suit the occasion. In colonial times many families tried to observe Christmas with ‘traditional’ Christmas dinners — roast beef or other roasted meat, baked vegetables and ‘plum’ pudding. Vestiges of this practice continue in the present, though chicken or turkey now often replaces roast beef. But the dense Christmas pudding retains a loyal band of followers, despite the hot conditions of a typical Australian Christmas, and recipes were printed in many of the newspapers in the lead up to the Festive Season in the early-twentieth century. In some families it was customary to insert coins into the batter when baking puddings. Threepences and sixpences were common. Those who found them (and managed not to swallow them) were said to have good luck for the coming year. I can still remember this as a child, along with the intense anticipation of searching for the coins. The advent of decimal currency put paid to this quaint custom, since the new coins were not suitable for baking. Some families, my own included, kept a store of old coins for the express purpose of baking them into the Christmas pudding for a while, but the point was rather lost once the coins were no longer legal tender and the ‘tradition’ gradually disappeared. In our household the pudding was replaced by the Christmas pavlova, which has since become ubiquitous in many Australian celebrations. Although invented much earlier, the popularity of the pavlova in the post-war period and beyond may well have reflected the spread of electric mix-masters and other kitchen gadgetry, that made beating egg whites to the requisite degree of volume and stiffness much easier. That said, when the Australian Women’s Weekly published The Christmas Book as one of its popular themed cooking book series, (reprinted ‘by popular demand’ in 1998), it featured a Christmas pudding on the cover.

‘How to make the perfect pavlova’, Australian Women’s Weekly, 27 November 1968, p.95

National Library of Australia

In the post-Second War period families often joined together at Christmas time for a large celebratory meal. This might be a semi-formal, sit-down affair, or a more relaxed ‘buffet’ style spread to which everyone contributed. As families became more diverse, so the food served evolved, but the tradition of a family celebration remained strong.

Extended Bunting Family sitting down to Christmas dinner, Dandenong North, 1983

Photographer: Ron Bunting

Reproduced courtesy Museums Victoria

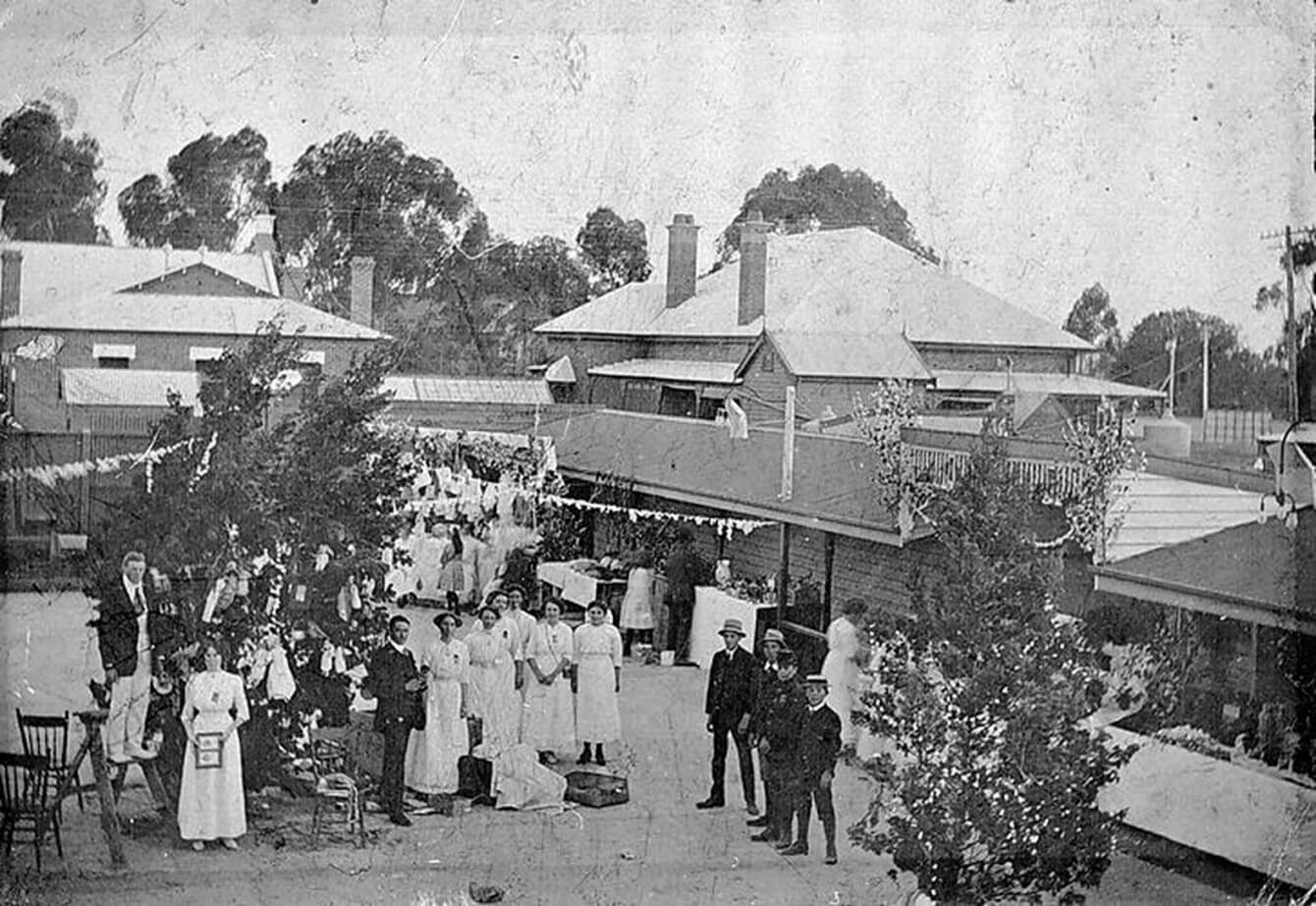

Sometimes communities celebrated en masse, as this photograph of the Mildura Town Christmas party in 1910 suggests.

Family birthdays

Other family celebrations marked significant individual milestones. Wedding anniversaries might prompt family gatherings, as might birthdays, or name days in some communities. Just when it became customary to bake the birthday person a special ‘birthday’ cake is less clear. The earliest advertisement for commercial ‘birthday’ cakes I found in a local newspaper appeared in the Herald in 1870, but home-baked cakes almost certainly preceded those. One earlier article referred to the practice of children decorating birthday cakes with ‘little flags’ (Australasian, 20 July 1867, p.27), but this was in an entirely different context and did not elaborate further. By the 1880s the birthday cake evidently featured as an entry category in local shows, as the results of the Dandenong Show, published in the Age in 1885, make clear (23 January 1885, p.6). Unfortunately, there is no further description.

The practice of decorating children’s birthday cakes with candles was evidently established in Victoria by 1906, when Mr. & Mrs. Manifold held a party at the zoo for their two little boys. After rides on the elephant and the train, guests were served slices of the birthday cake, which was decorated with ‘five small white candles’. Gas-filled balloons were also presented to the children. (Reported in the Australasian, 15 September 1906, p.44). Another article, offering helpful hints on how to secure candles on the birthday cake, also made it clear that the candles were all to be blown out before the cake was cut. (Argus, 31 May 1911, p.15) These are ‘traditions’ that are repeated at children’s birthday parties to this day.

Children’s birthday party, Caulfield 1946

Three of the children shared a birthday and often celebrated it together, although it is interesting that each has a birthday cake!

Reproduced courtesy Museums Victoria

In the post-war period the birthday cake was often a filled sponge cake, as shown in the illustration from Caulfield in 1946. My own mother made a version of this that she called a ‘Napoleon’ cake for our birthdays, although whether it had any actual association with the famous emperor I have no idea. It consisted of a base of puff pastry, and then two layers of sponge, each layer topped with jam and cream. Whipped cream was spread on the top, with candles. Modern ‘Napoleon’ cakes seem to consist of very thin layers of puff pastry filled with confectioners cream, more like a torte, so my mother’s cake may have been a simpler version modified for children.

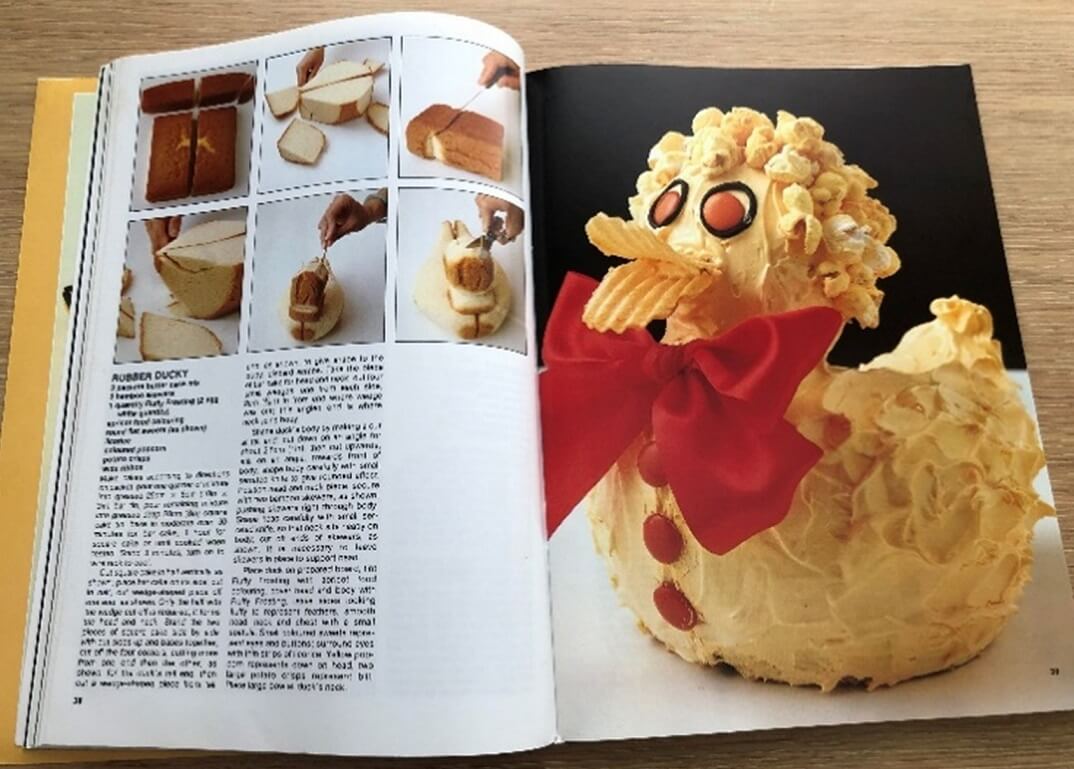

The Australian Women’s Weekly Children’s Birthday Cake Book

The advent of the Australian Women’s Weekly Children’s Birthday Cake Book was a game-changer in the home birthday cake stakes. First published in 1980, it featured colourful iced cakes in imaginative shapes, with step-by-step instructions for decoration and assembly. The emphasis was on decoration rather than proficiency in baking and controversially, the recipes suggested using packet cake mix. After a slower than expected start, the book quickly became a best seller and has remained in print ever since. Children loved its illustrations and often spent weeks poring over the illustrations as their birthdays approached, while their anxious parents (I was one) tried to steer them towards something that looked achievable. Some emerged as enduring favourites — the duck cake for example — immortalised in recent times in an episode of the popular animated feature Bluey (season 2, episode 43). Choosing and making a cake from the Weekly’s Children’s Birthday Cake Book became a tradition in many Australian families in the decades after 1980 — an example of the way in which family ‘traditions’ continue to be invented, enjoyed, and even exported. I know of one young woman, a Danish-English Australian, who loved the Birthday Cake Book in her childhood. Now living in Germany, with an American partner, she recently baked a cake from the Birthday Cake Book for her five-year-old daughter. For an exploration of the impact of the Birthday Cake Book you can hear historian Lauren Samuelsson on the Old Treasury Building YouTube Channel.

Traditional craft practices

Following traditional craft practices is another way in which families preserve knowledge and identity. In the case of First Nations peoples this can involve maintaining, and adapting, craft traditions that are thousands of years old. In the Belongings exhibition we exhibit two exquisite woven baskets, made by Aunty Marilyne Nicholls. First Nations women in the southeast of Australia have practised this style of weaving, coiled basketry, for many thousands of years, learning the techniques through Cultural Storytelling. Initially made from cumbungi (bulrush) and native sedges, wrapped and stitched together, the baskets were used for carrying special materials, collecting and storing food such as murnong (yam daisies) and other bush tucker.

Aunty Marilyne Nicholls is a master weaver and descendent of the Freshwater Murray River Peoples and Saltwater Peoples of the Coorong Coast in South Australia. Born in Swan Hill in 1957, Marilyne is a direct descendant of Sir Douglas Nicholls, renowned sportsman, pastor and campaigner for Indigenous rights. The weaving of plant fibre baskets is inextricably linked to place, and originates from cultural expression via ceremony, kinship, trade and exchange. Aunty Marilyne was taught to harvest and incorporate pine needles into traditional weaving techniques by her mother and grandmother, when farming and development reduced access to the native plant materials. Marilyne has passed on this skill to her daughter, Letty. You can listen to her speaking about the significance of traditional weaving through the Koorie Heritage Trust.

These are just some of the ways in which families in Victoria preserve traditional practices. Some link people in the present with ancestors across many generations, while others are of recent invention, but all help to maintain a sense of identity and of belonging.

Further reading

Eric Hobsbawm & Terence Ranger (eds) The Invention of Tradition. Cambridge University Press, 1992 edition. First published 1983.

Daniel Miller The Comfort of Things. Cambridge, Polity Press, 2008.

Rosalina Pisco Costa, ‘Family Rituals: Mapping the Postmodern Family Through Time, Space and Emotion’, Journal of Comparative Family Studies, Vol. 44, Issue 3, May-June 2013, pp. 269-89.

Elizabeth H. Pleck Celebrating the Family: Ethnicity, consumer culture and family rituals. Harvard University Press, 2000.