Family photographs preserve our memories of formal or everyday events. They decorate our walls, fill the cupboards of our homes, and are stored in their thousands on smart phones and desktop computers. But this is a relatively recent development. Until well into the twentieth century, photographs were reserved for the wealthy.

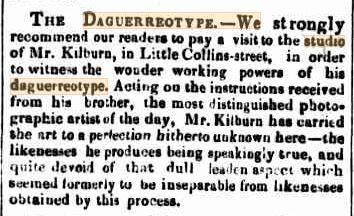

The Daguerreotype

The first commercially-successful photographic process was the daguerreotype, brought to Melbourne in about 1845. For the first time families could obtain a ‘truthful likeness’, but it was only available to the upper classes. While much cheaper than a painted portrait, a photograph still cost about 21 shillings, the equivalent of a full week’s wage for a labourer at the time.

Invented by Louis Daguerre in 1837, the daguerreotype image was formed on a silver-coated sheet of copper. It was a complex process. First the copper plate had to be cleaned and polished. It was then sensitised in a closed box with iodine vapours and transferred to a large box camera. After being exposed to light the plate was developed over hot mercury. To fix the image the plate was immersed in salt water or ‘hypo’ (sodium thiosulfate), then treated or ‘toned’ with gold chloride. Being a ‘direct-positive process’, no negative was made: each daguerreotype was unique and could not be duplicated.

It took considerable patience to pose for a daguerreotype. Lengthy exposure times meant that the sitter had to hold still for up to a minute, trying not to blink or breathe:

The sitters in historic photographs often appear sombre or stern. This effect comes less from a universal displeasure with being photographed and more from the concentration required not to move during the photograph and blur the image.

DeCourcy, E., ‘How recreating early daguerreotype photographs gave us a window to the past’, The Conversation, 17 February 2022

The surface of the daguerreotype was highly sensitive and required a case and glass cover to protect it. The cases are often beautiful objects, made of embossed leather (usually a paper-thin sheepskin), paper or cloth. We have one such example on display in our exhibition, Belongings: Objects and Family Life.

From the 1860s, as photography evolved, it became more accessible. The daguerreotype was superseded by new formats, ranging from the ambrotype (glass-plated) to the popular carte-de-visite (card-mounted print). But photographs were still a novelty. Most were taken in a photographer’s studio, presenting the sitter in his or her Sunday-best.

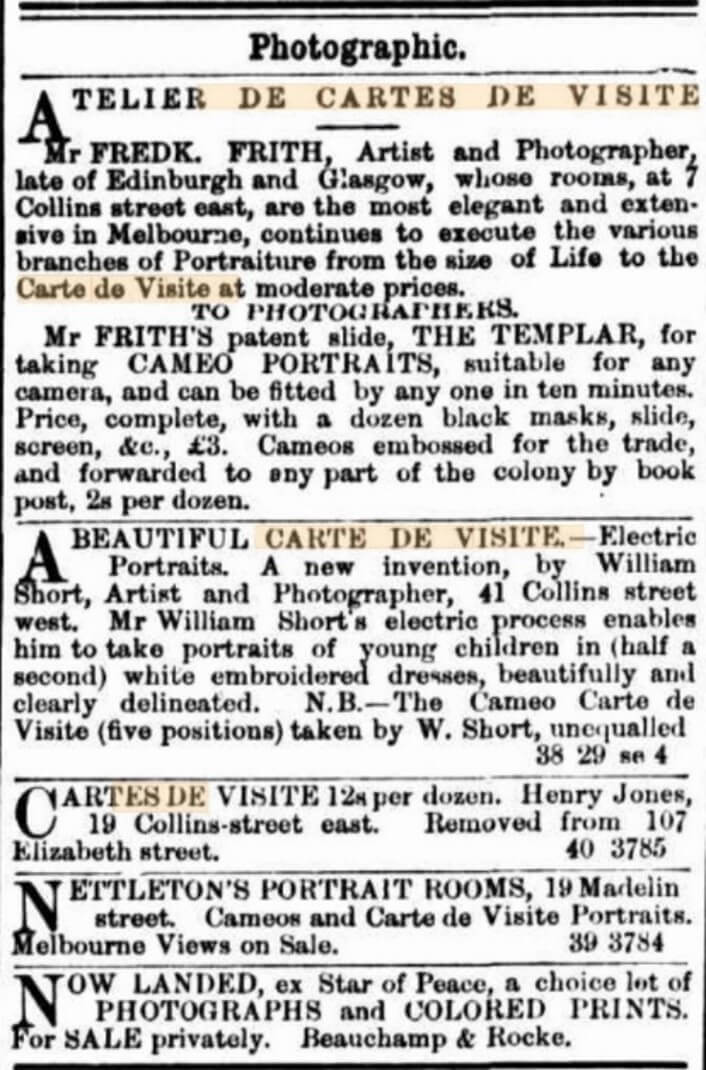

The Carte de Visite

Patented by photographer André Adolphe Eugène Disdéri in Paris in 1854, cartes de visites were small cards, with a black-and-white photograph attached.

Disdéri’s invention used a camera with four lenses, which resulted in four identical images on the negative. This allowed photographers to create several copies of the same image, reducing processing costs and wastage.

Designed to be held in the hand, or housed in custom-made albums, cartes-de-visite are small, humble objects. The upper and lower classes, famous and anonymous people were all now able to have their studio portrait taken – many for the first time.

Maggie Finch and Laura Jocic, ‘Rethinking an unknown carte-de-visite’

Cartes were incredibly popular. In England, about 300 million were sold in just six years, between 1861 and 1867. Commercially-made, ready-to-use ‘albums’ were available to purchase: Queen Victoria apparently compiled more than one hundred albums, featuring royalty and others of social standing.

Cartes were equally popular in Australia. By the 1860s ‘cartomania’ had reached its peak and photographers in Melbourne touted for trade. One studio boasted that it had produced over 30,000 portraits during the 1863-64 summer months.

People began to collect portraits of their children and parents, assembling them in albums with pages perforated with slots or windows. Cartes were exchanged between family members and friends: unlike the daguerreotype, cartes could be sent through the mail without the need for a bulky case and fragile cover-glass. Cartes of royalty, celebrities and war heroes were sold at stationer’s shops in the same way that postcards are today. Well-off families would keep albums full of images of family and friends, displayed with those of celebrated persons.

According to historian, Susan Long, the carte album was the precursor of the family photograph album and ‘provided a repository for the documentation of Victorian family life’:

The carte album held social currency: who and what were collected were often perceived to reflect the owner’s social status. The album was akin to a 19th-century social inventory.

Susan Long, ‘Self-representation in the nineteenth century’, The La Trobe Journal, No. 106, September 2021

Indeed, the photographs conveyed more than physical features and clothing: ‘They announced that the sitter could afford to have a picture taken and was sufficiently confident to exhibit it.’

The format remained popular until the early-twentieth century, and cartes can still be found in large numbers in museum and library collections, loose or in family albums.

This album of carte-de-visite photographs was compiled by Jane Ingram, née Pullen, between 1875-1905. Jane’s husband, John Ingram, was a gold miner and the family appears to have been relatively well-off. The family lived at 68 Barnes Street in Stawell, about 240 kilometres west of Melbourne.

Each carte is mounted in windows in the cardboard leaves. Some photographs are mounted singularly: others up to four per leaf. Many of the leaves have hand-painted floral decoration.

Album of carte-de-visite photographs compiled by Jane Ingram ,née Pullen, Stawell, Victoria 1875-1905. Cartes-de-visite, introduced in the 1860s, were a small card-mounted portrait photograph — cheap, easily available, and potentially mass-produced.

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

The Kodak camera

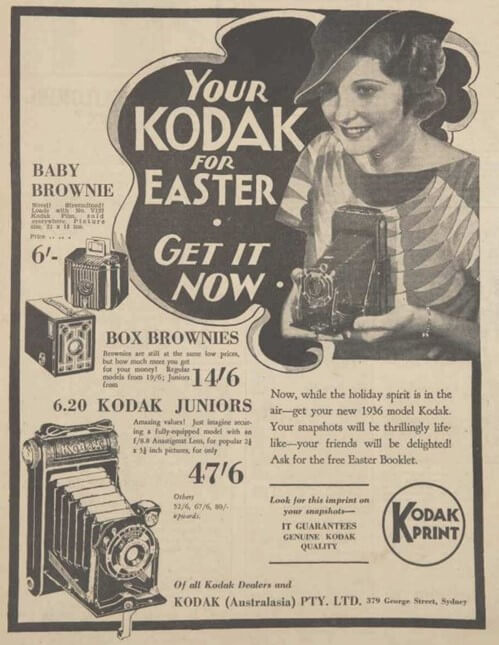

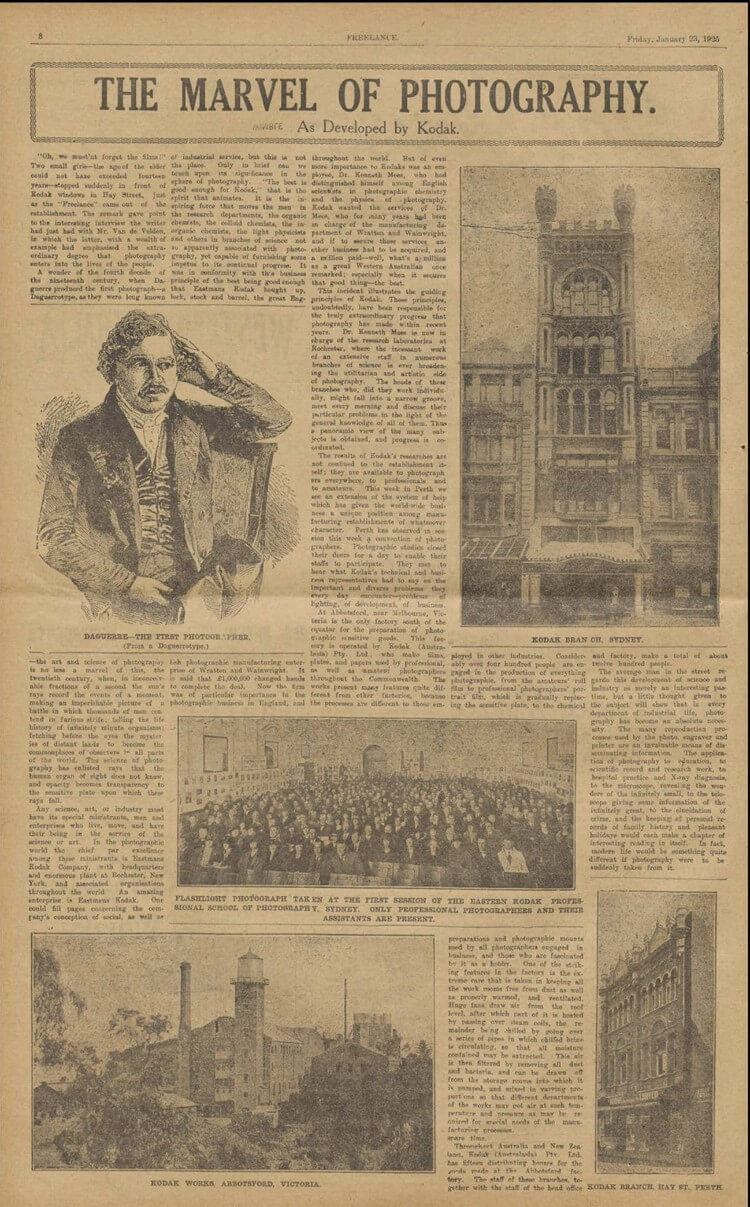

Photography, or rather, the concept of a ‘family photograph’, changed in 1888, when George Eastman patented his first Kodak camera. By simplifying the equipment and even processing the film for the customer, Kodak ‘democratised’ photography, making it available to millions of people with no training or technical expertise. Kodak’s claim, ‘You press the button, we do the rest’, meant that photography was no longer restricted to professionals, or limited to staged portraits posed for in a photographer’s studio.

The first Kodak – Kodak #1 - was a simple box camera: it sold in America for $25 in 1888. Unlike earlier cameras that used a glass-plate negative for each exposure, the Kodak came pre-loaded with a 100-exposure roll of film. After finishing the roll, the customer mailed the camera back to one of Eastman’s factories, in Rochester, New York, or Harrow, Middlesex, England, where the roll was processed and printed. Developing and printing cost $10. The camera, loaded with a fresh roll of film was then returned with the negatives and mounted prints.

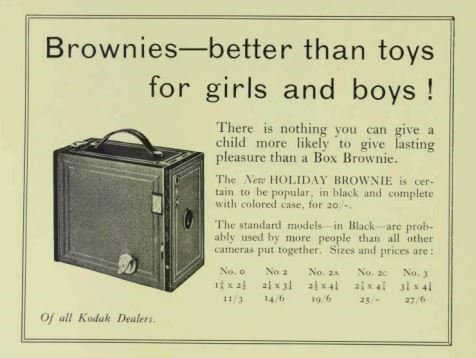

In 1900 Kodak introduced the ‘Brownie’ camera, another simple and even cheaper box camera. The Brownie sold for just one dollar (about $50 today): the required film was likewise affordable, as was processing the shots by sending them to Kodak or a local lab.

Before the Brownie, taking a photograph was a complex procedure:

A glass plate was installed in the back of the camera by the photographer; he (in almost all cases it was a ‘he’) then allowed light to pass through the lens of a camera, which focused it on the pre-sensitized glass plate; the photographer then carefully removed the plate from the camera and stored it away from all sources of light; this plate was later treated by the photographer, using a number of chemicals in a darkroom. Moreover, the photographer needed to carry a stack of glass plates whenever he ventured out of the studio, whether to cover a war or some other event.

Munir & Phillips: The Birth of the ‘Kodak Moment

Cheap, simple, and sturdy, the Brownie targeted buyers with no previous experience of photography ― a novelty at the time. The hard work of film-developing and photo-printing was reserved for the Kodak laboratories: shooting pictures was presented as simple enough for even women and children to master.

The Brownie Camera was the first camera to be marketed explicitly to children (and women).

The Kodak was a camera for everyone, supported by an industry dedicated to processing and printing the photographs.

The ‘Brownie’ was enormously popular and countless millions were sold. In fact, by 1905 an estimated ten million Americans had bought one! Such was their popularity that the word ‘Kodak’ became part of everyday vernacular: the phrase ‘Kodak moment’ (meaning a photo opportunity) was introduced in the early-twentieth century and is still used today.

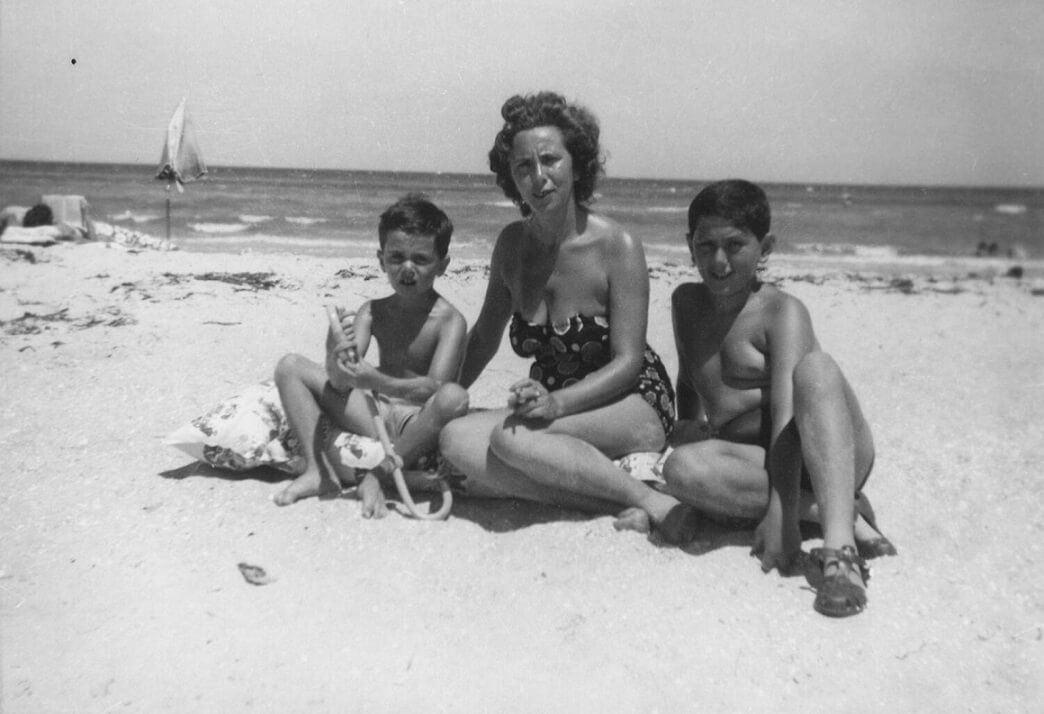

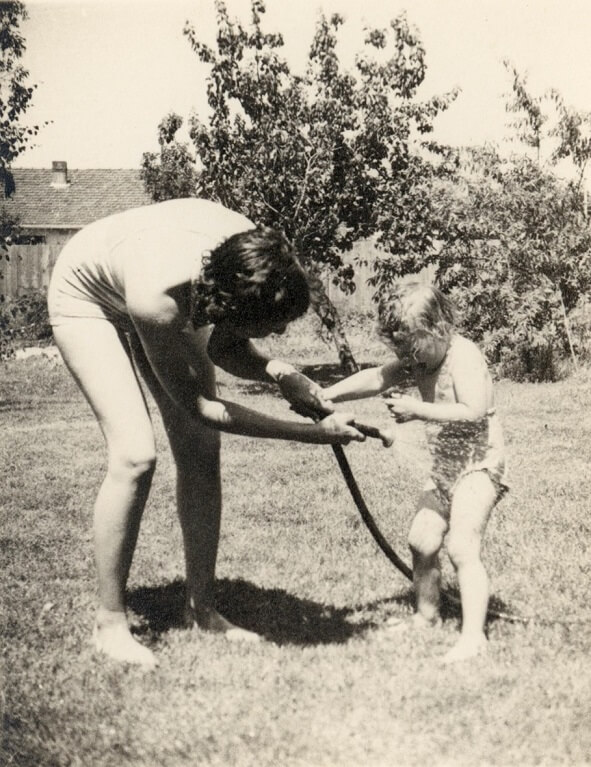

For the first time, people began to record their everyday lives. By the 1960s most Australian families owned a camera. People took pictures of their families at the beach, their children riding their first bicycle, at birthdays or simply at home: the snapshot was born. Kodak advertisements featured the slogans, ‘All out-doors invites your Kodak’, ‘Kodak as you go’ and ‘Don’t let another weekend slip by without a Kodak’. With 100 possible ‘snaps’ in the film roll, each picture became less precious.

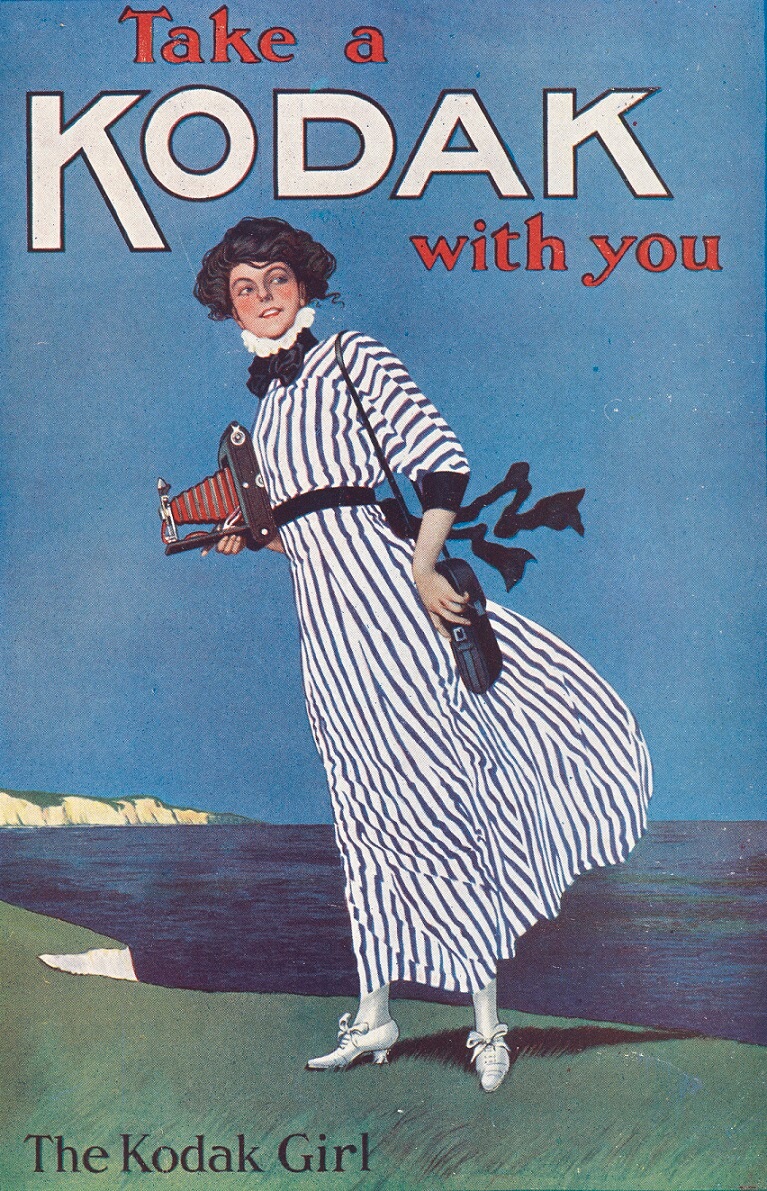

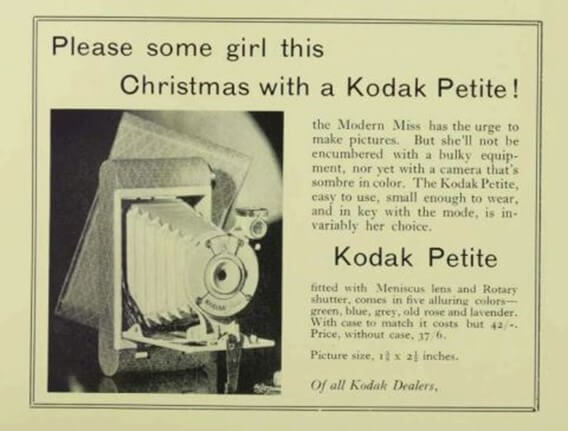

Kodak encouraged women, previously excluded, to embrace photography as a hobby. They designed ‘Petite’ cameras and an art deco line of ‘Vanity Cameras’, and clever marketing featured the ‘Kodak Girl’: a young, glamorous, fashionable woman. And it worked. Women soon became the largest consumers of Kodak's snapshot cameras, film, and products.

Kodak Girl symbolized the modern, adventurous, independent female and was soon to become the company’s central image. Featured first on posters and then on 2-m high cardboard cut-outs, Kodak Girl models also made live appearances at stores.

The ’Kodak Girl’ personified both photographer and model and remained a key figure in Kodak advertising copy until the 1960s.

Eastman invented a camera simple enough for anyone to operate, then proceeded to market it to women.

Kodak commercials also took advantage of the strengthening discourse surrounding a ‘mother’s love’. Women were encouraged to be archivists, meticulous chroniclers of family life:

Women were seen as the memory keepers of the family. It was their duty to make sure that the precious moments of their children’s lives were captured. Birthdays, first steps, holidays, graduations ― all needed to be recorded and saved for posterity, and it was up to women to make sure that happened.

The snapshot evolved, with mothers urged to curate ‘an intimate snapshot diary covering the entire period from cradle days to full manhood or womanhood.’ Kodak guides advised women on what would make the perfect picture:

Baby taking a bath, Junior riding his first two-wheel bicycle, Sis trying on Mom’s [sic[ clothes, Dad creating something in his shop, Mom [sic] tending to her prize flowers, the gang cavorting at the beach or painting posters for a school dance – all these things make good picture subjects’.

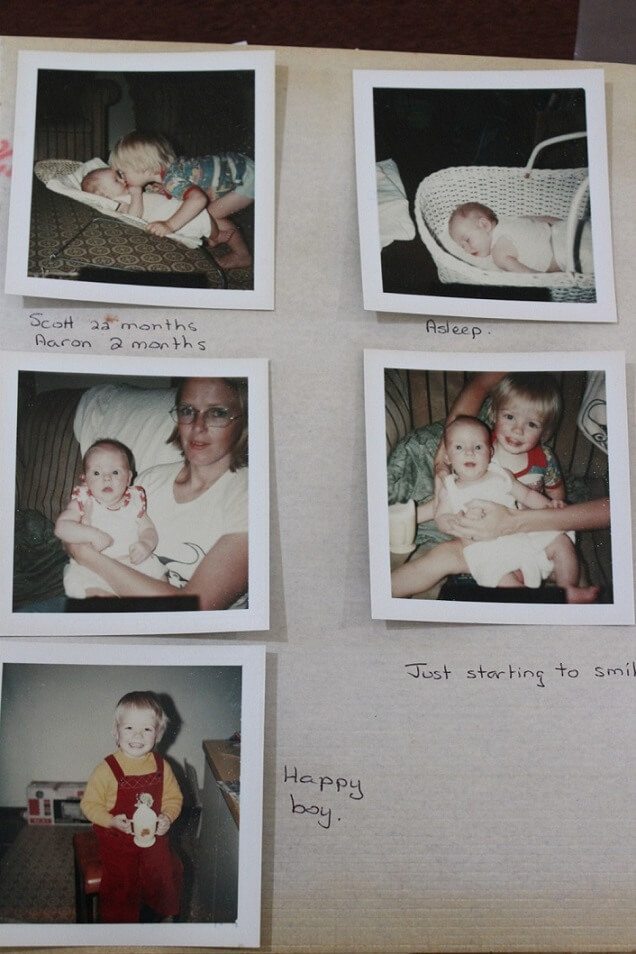

These casual snapshots were intimate and spontaneous; taken more frequently than studio portraits, they showed the subject in a variety of situations or events.

With snapshots came the photo album. Kodak encouraged women to preserve their images in photograph albums.

Albums like this became more common from the mid-twentieth century. Family albums were typically added to over time, with pictures sometimes spanning generations. More often than not the creators were women.

Far from home

For migrants, when computers were unknown and phones expensive, photography communicated their new lives to relatives and friends in their home countries. Snapshots of the casual Australian lifestyle were particularly common, with beach scenes, family picnics and backyard views.

Photograph of Setsutaro Hasegawa with his son, Leo, and grandchildren Leonard and Matsu, in his backyard at Little Ryrie Street, Geelong, c.1933. Setsutaro migrated to Australia from Japan in 1897 at the age of 26, just four years before the introduction of the Immigration Restriction Act (popularly known as the ‘White Australia Policy’) which limited non-white migration to Australia. He established a laundry business in Geelong and, in 1911, married an Australian woman. They had three children.

In 1941 Setsutaro was arrested as an enemy alien and sent to Tatura Internment Camp in northern Victoria. He was released early in 1943 due to his age and poor health but, unlike most Japanest interns, was not deported to Japan after the War. Setsutaro lived in Geelong with his family until his death in 1952.

Photograph reproduced courtesy Museums Victoria

Dimitra Papadimitropoulos recalls:

'Picnics for the whole family, with people from both Athanasia and Konstantinos' sides, including even extended cousins by marriage, and their children. They would have taken an elaborate picnic with spanakopita, tyropitas, boiled eggs and salads, meat loaf, cooked chicken, lots of feta cheese, home grown tomatoes, but no sandwiches. An unbelievable feast.'

'They liked to travel out to Bundoora, to the beach, and to Whittlesea. At the beach, they never would picnic on the sand, always on the grass under the trees. They had to be at the beach at 7.00 in the morning to get the best spot. It would be so cold everyone would be freezing and wrapped in blankets, and then they would warm up as the sun rose. These days the parents go at 7.00 in the morning to pick the spot and the younger generation come at 11.00 am.'

James and Eileen Leech and their toddler daughter, Susan, migrated from Manchester, England, in November 1953 under the ten pound assisted migration scheme. James, who had served with Australian soldiers during World War II was excited by the move. Eileen, with strong family ties in Britain, was reluctant to come. Eileen’s homesickness eventually led to depression and when she fell pregnant in 1956 the family returned to England on medical advice.

Mary Louey Gung with her children at Aspendale beach, Melbourne, c. 1949

Reproduced courtesy Museums Victoria

Discover more about the Gung family and their migration history at Museums Victoria.

Kodak in Australia

Thomas Baker, an English scientist, entrepreneur and philanthropist, started a photographic business selling Baker’s Gelatine Plates in Abbotsford, Victoria in 1884. In 1887 Baker teamed up with John Joseph Rouse to form Baker & Rouse, before amalgamating with Eastman Kodak in 1908 to form Kodak Australasia.

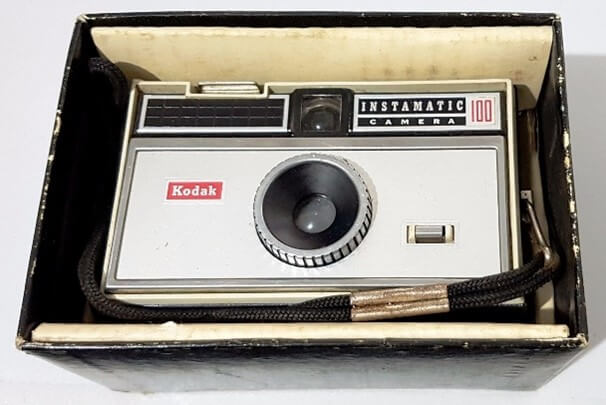

On display in Belongings: Objects and Family Life we have two Australian-made Kodak cameras ― the ‘Brownie Flash II’ and ‘Kodak Instamatic’.

‘Brownie Flash II’, late 1950s

Old Treasury Building Melbourne

The Kodak Brownie Flash II camera was a small box camera with side contacts for a flash attachment enabling indoor and night photography. It had a leatherette cover and a metal front face, with view finders on the top and the side. It was first made in the USA between 1957 and 1960, with the Australian-made model, which also started production in 1957, continuing until around 1963.

The Kodak Brownie Flash II was the first camera to be produced locally in Australia at Kodak Australasia's Abbotsford factory. Parts for local products were imported from England for Australian assembly.

‘Kodak Instamatic’, from 1963, made by Kodak Australasia Pty Ltd.

Old Treasury Building Melbourne

The Kodak ‘Instamatic’ was introduced in 1963. Small, compact, and easy to use, the camera had a huge impact on amateur photography. It featured easily loaded film cartridges: users dropped a film cartridge into the back of the camera. The cameras had a flash for indoor and night photography and took colour and black & white print film as well as colour slide film.

Instamatics were produced in Melbourne by Kodak Australasia. There was a wide range available, ranging in price from just $5.95 to over $100. More than 75 million Instamatics were sold worldwide.

Further reading

Online sources

Museums Victoria

National Gallery of Victoria

National Library of Australia

Powerhouse Museum

State Library Victoria

Publications

Adam Ethan Berner, ‘Making a Family: The history and theory behind family photos’

Angeletta Leggio, ‘A history of Australia’s Kodak manufacturing plant’

Ann Copeland, ‘Who’s that girl? Dating a 19th century photograph’

Barbara Levine and Stephanie Snyder, Snapshot Chronicles: Inventing the American Photo Album, New York, Princeton Architectural Press, 2007

Blake Morrison, ‘The Power of Photography: Time, Mortality and Memory’

Carly Earl and Margot Riley, ‘From daguerreotypes to glass plate negatives: Australia’s oldest images – photo essay’

Christina Kotchemidova, ‘Why we say “Cheese”: Producing the Smile in Snapshot Photography’, Critical Studies in Media Communication, Vol. 22, No. 1, March 2005

Elisa DeCourcy, ‘Remaking history: how recreating early daguerreotype photographs gave us a window to the past’

Elizabeth Siegel, Galleries of Friendship and Fame: A History of Nineteenth-Century American Photograph Albums, New Haven, Yale University Press, 2010

Helen Ennis, ‘Other histories: photography and Australia’, Journal of Art Historiography, No. 4, June 2011

Jaap Boerdam and Warna Oosterbaan Martinius, ‘Family Photographs – A Sociological Approach’, The Netherlands’ Journal of Sociology, Issue 16, 1980

Jason Benjamin, ‘A case for photographs’, University of Melbourne Collections, Issue 5, November 2009

Jeffrey Mifflin, ‘Metaphors for Life Itself’: Historical Photograph Albums, Archives and the Shape of Experience and Memory’, Review Essay, The American Archivist, Vol. 75, Spring/Summer 2012

Kamal A. Munir and Nelson Phillips, ‘The Birth of the ‘Kodak Moment’: Institutional Entrepreneurship and the Adoption of New Technologies’

‘Kodak in Australasia’, Museums Victoria

Mette Sandbye, ‘Looking at the family photo album: a resumed theoretical discussion of why and how’

Mia Fineman, ‘Kodak and the Rise of Amateur Photography’

Nicolá Goc, ‘Snapshot Photography, Women’s Domestic Work, and the “Kodak Moment”, 1910s-1960s’

Stephen Burstow, The Carte de Visite and Domestic Digital Photography

Susan Long, ‘Self-representation in the nineteenth century’, The La Trobe Journal, No. 106, September 2001