Have you ever really thought about the objects in your life ― your telephone, TV, recipe books, a childhood toy perhaps? How important are these objects to you or your family? Are there things you absolutely cannot live without?

What about the car? If there was any single object that defined the twentieth century, and the twentieth-century family, it might just be the motor car.

The early-twentieth century

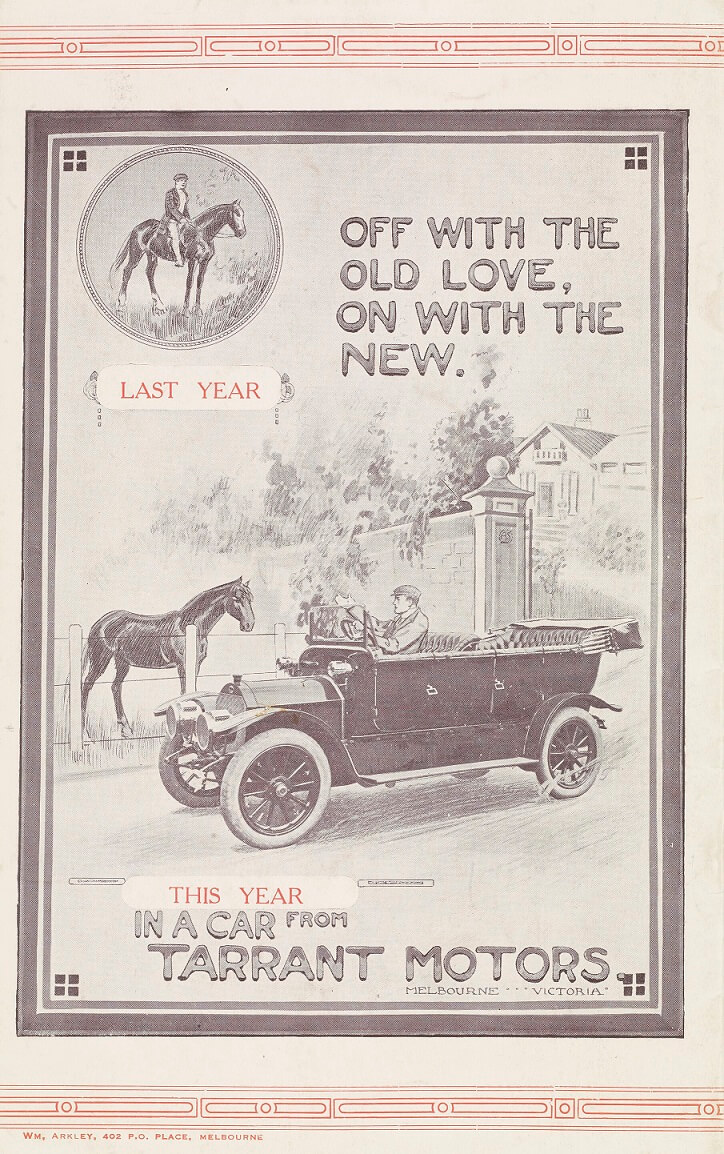

The first vehicle with an internal combustion engine to be made in Australia was made in 1901 by local company, Tarrant Motor and Engineering Company. Tarrant’s first car was a two-cylinder, two-seater petrol motor car with an imported Benz engine: later, they refined it with their own, locally made engine. Tarrant occupied several buildings in Melbourne with separate departments for machining, bodybuilding, assembly, painting and repairs.

The number of motor cars on the roads climbed steadily in the years before World War One. This trend continued into the 1920s. The number of vehicles on Victorian roads doubled from 70,000 in 1924 to 154,000 in 1929.

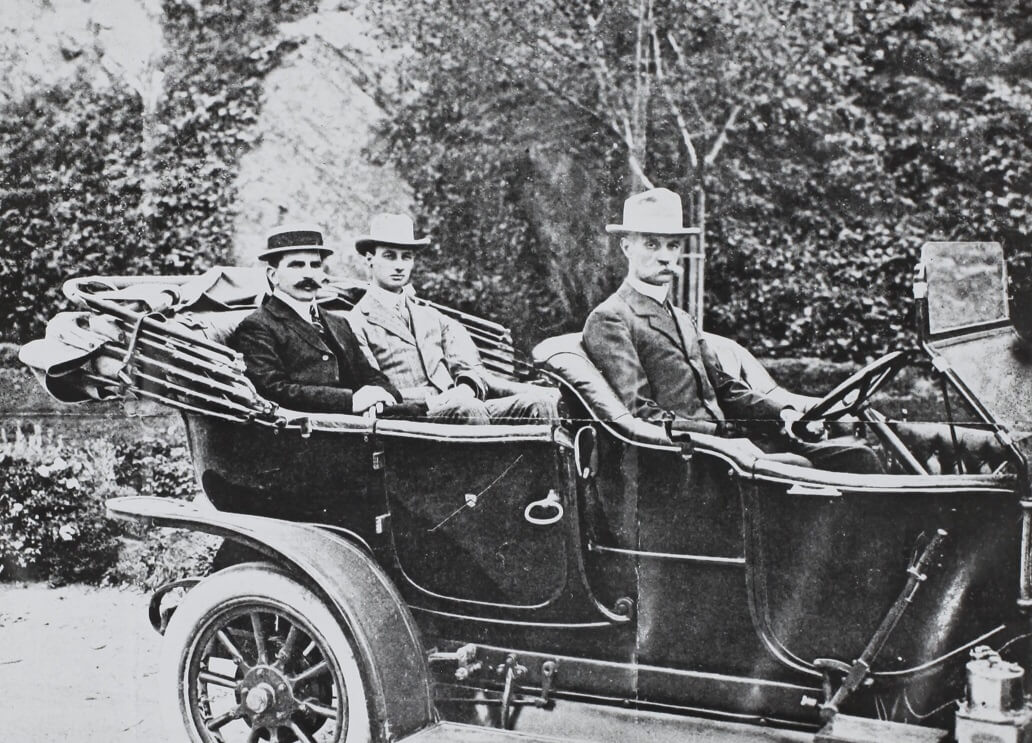

The first Australian-made petrol-driven car was built by Melbourne engineer, Harley Tarrant, in 1901. This photograph shows the ‘Tarrant No 2’ motor car outside the Tarrant Motor factory in South Melbourne. At the wheel is W.H. Chandler, an early motoring enthusiast, with his brother as passenger, c.1901.

Reproduced courtesy Museums Victoria

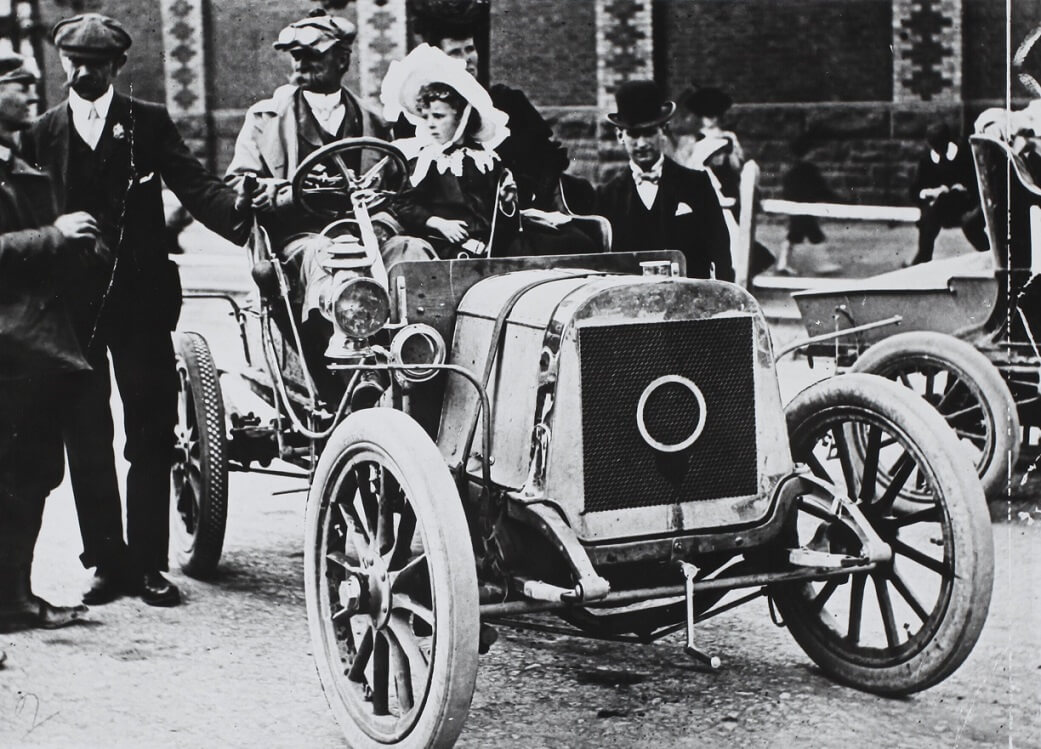

This photograph shows Tarrant at the wheel of his ‘Tarrant Number 6’, with his wife and daughter. The car was priced at £375, more than twice the average yearly wage for a factory worker at the time.

Reproduced courtesy Museums Victoria

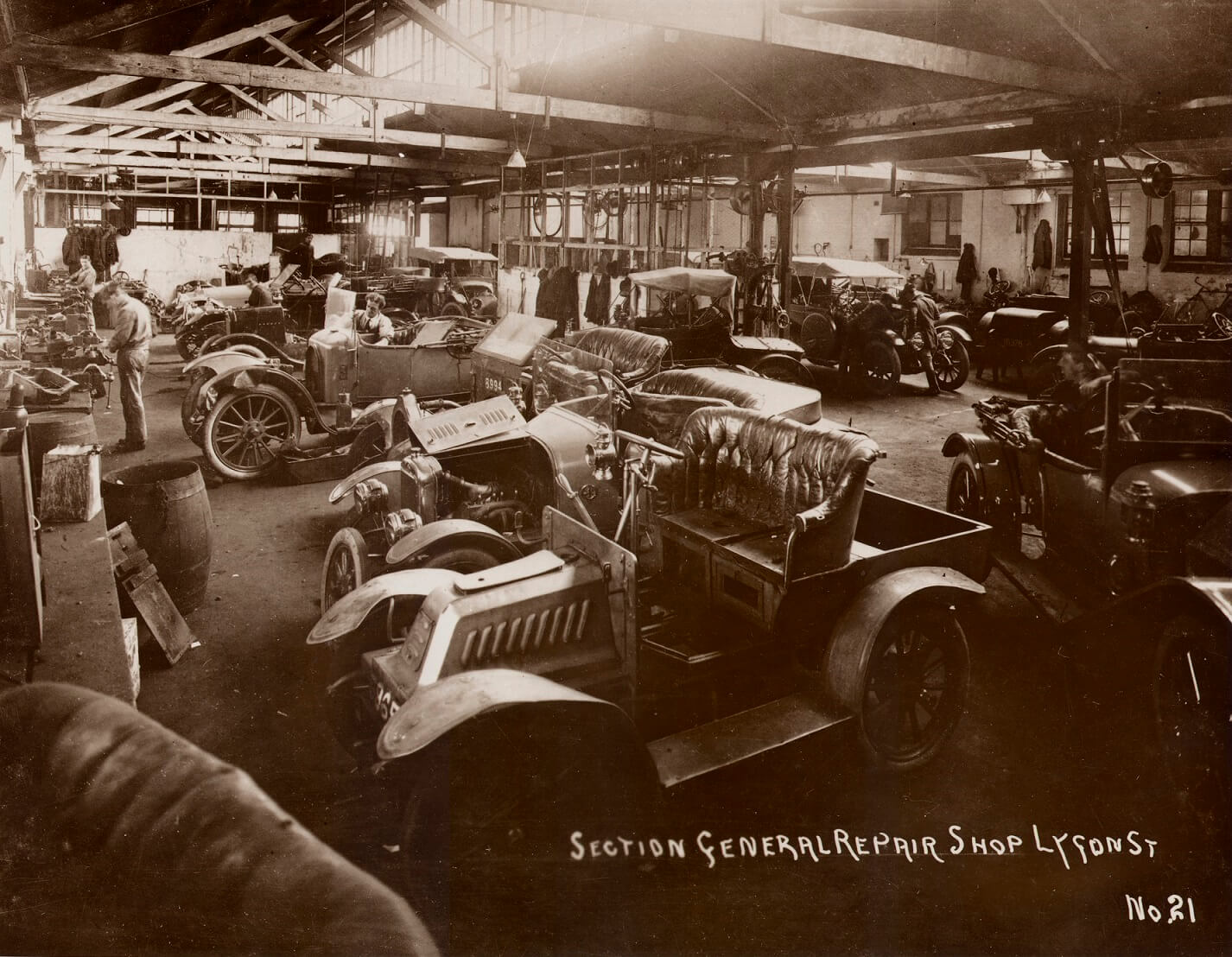

Repair shop at the Tarrant Motor and Engineering Co., Lygon Street, c.1920

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

As motoring grew in popularity, so did the factories. By 1926-7 over 90,000 car bodies were manufactured in Victoria, with a few large companies dominating the market. Ford built a major assembly plant in Geelong in 1925, while Holden (merging with General Motors from 1931) established a plant at Fishermans Bend.

In 1925 there was one motor vehicle to every 24 Victorians: by 1930 approximately one family in three owned a car, but the onset of the Depression slowed production. Discover more about Victoria’s car manufacturing history here.

During World War Two the GMH factory produced more than 30,000 vehicle bodies for the Australian and United States forces and manufactured a wide range of equipment, including field guns, aircraft, aero and marine engines.

After the war they built their first fully-Australian product, the 48-215, also known as the ‘FX’. GMH was the first of several automotive works in the Fishermans Bend area, close to rail and sea transport, and nearby workforce.

A menace on the roads

The real truth is that when the motor comes into universal use life will not be worth living.

To live in a city when motors have superseded horses will be like living in a cotton mill, with a boiler factory on one side and a merry-go-round with a steam organ on the other. ... A horse does not like to run a man down if he can help it, but a machine of steel and brass will delight in killing people.

The Argus, 12 December 1900

Motor cars were a new and dangerous force in the city. Historian, Graeme Davison, explained:

They travelled faster, generated more noise and dust and claimed more road space than any other form of transport. They endangered the lives of anything, human or beast, that was unfortunate enough to stand in their path.

Few regulations were imposed on early motorists and pedestrians and cyclists complained of ‘road hogs’ speeding through city streets:

MELBOURNE LETTER.

(From Our Correspondent.)

MOTOR CAR TRAFFIC

The motor evil in Melbourne is attracting more and more public attention; but the police seem unable to grapple with the question and the authorities are not very active in helping them. There is an old saying in England that it is necessary to kill a bishop before an evil will be removed. In Melbourne motor cars have killed a clergyman and several other people, but still they go the noisy tenor of their ways, heedless and careless of common pedestrians. At one time in Melbourne there was considerable outcry at the pace cyclists rode, and special constables who were expert riders were mounted on racing machines to catch the offenders. In a very little time, the evil was supressed. But no such action is taken with motor cars. A policeman is expected to guard the road on an ordinary bicycle, and the consequence is that when he sails after a motor he is left hopelessly in a cloud of dust. Generally the motorist does not know he is being followed; and when he does know he pretends he doesn’t.

North Eastern Despatch, 26 November 1907

REPORT ALL ACCIDENTS

“Lead” writes: ―

Mr E. T. Holmes is imperiously impertinent in commanding that young children and elderly unfortunates should fly for shelter at the sound of his squawking horn.

If there were necessity for speed, there would be some excuse for it, but in some cases, especially at night, these over-driven cars contain half-drunken Toorak bloods, merely out for a “show off”. In fact, it is now recognised as “the correct thing” to sojourn to certain “pubs” in the outer suburbs and break the Chapel street record on returning.

Years ago, when Melbourne streets became dangerous through traction engines and flying butcher boys’ carts, the law stepped in and stopped these nuisances. Now-a-days, motor-cars, without hindrance ―and a thousand times worse ― make a hell of our fair city, apparently because the greater portion of the community is so soddened with religion, sport and other intoxicants that it is too weak to rise against the indignities of Toorak.

Motor-cars should not be permitted to travel faster than the trams in the metropolitan area. In the county, let the “hog” break his neck if he so choose and has enough “gold-top” on board to give him the Dutch pluck to do so.

As a pedestrian and a cyclist, I have had such narrow escapes that I have almost made up my mind to carry a “shooter” and if ever I be stricken down by one of these men ― should I have strength enough left to pull a trigger before being carried to the hospital or the morgue ― to treat the occupants to a shower of lead.

The Herald, 31 August 1909

Note. The average running speed of Melbourne’s cable trams around this time was 8.9 miles (about 14kms) per hour.

The first pedestrian to be struck and killed by a car in Melbourne was 47-year-old Thomas Hall, an iron worker at Messrs J and T Muir’s iron foundry. On 24 August 1905, while crossing the intersection of Nicholson and Gertrude Streets in Fitzroy, Hall was struck by an automobile driven by Macpherson Robertson. (Owner of the MacRobertson’s confectionery empire later to produce the Cherry Ripe and Freddo Frog.). Robertson drove Hall to the hospital, but Hall was declared dead on arrival. Robertson was later exonerated of any blame, with evidence at the coronial inquest suggesting the dead man was intoxicated when he crossed the road into the vehicle’s path:

At the adjourned inquiry held by Mr Candler to-day, a number of witnesses were examined, and they generally concurred in the view that Mr Robertson was driving slowly when the unfortunate affair occurred. One witness, Mr George Tapnell, estimated the speed at about 14 miles an hour, but others put it down at eight or nine. Three of four policemen spoke well of Mr. Robertson as a careful driver. There was evidence that Hall was under the influence of drink at the time, and that drink trouble had interfered with the regularity of his employment as an ironworker. Mr Robertson said that he crossed the intersection slowly – about six or seven miles an hour, and that after he got across a man suddenly made his appearance alongside the car… The Coroner found that no blame attached to the driver.

Macpherson Robertson driving his Oldsmobile, 1925

Reproduced courtesy Royal Historical Society of Victoria

A wealthy businessman, Robertson purchased his first car, a French Rochet in 1902, and later bought an Oldsmobile, pictured above.

MacRobertson delivery vans, c. 1924

Reproduced courtesy Royal Historical Society of Victoria

By the 1920s Robertson had a fleet of branded lorries and cars to distribute his chocolate products

With more cars on the roads, accidents were frequent, and there were calls to control the ‘horseless carriage’:

We have not a great many motor cars here, but we have, I think, developed one or two gentlemen who are what are called in the old country “road hogs” — who drive their cars furiously and ought to be stopped.

Donald MacKinnon ― Victoria, Parliamentary Debates, Legislative Assembly, 1905

The first proposed Motor Car Bill was introduced in the Victorian parliament in 1905. The bill called for speed limits, penalties for various offences, registration of all cars and licensing of drivers, but the regulation of motorists was resisted. Motoring lobby groups like the (recently-formed) Automobile Club of Victoria (ACV) proved resourceful and powerful, and the bill failed.

A new Motor Car Act was proposed in 1908 and passed in 1909. Under the Act motorists were required to stop when there was an accident, all vehicles needed lights and a bell or a horn, vehicles had to display a registration number, and all drivers had to be over 18.

The speed of motor vehicles was regulated through a new offence of ‘driving recklessly, negligently or at speed’, determined with ‘regard to all the circumstances of the case, including the nature, condition and use of the highway and to the amount of traffic’. Legislation allowed local councils and shires to set speed limits, and some of them did. Brighton Council set speed limits of 10 mph, with 5 mph over crossings. St Kilda passed a by-law limiting speed to 12 miles per hour.

From 1914 further restrictions were introduced by the Melbourne City Council. Motorists were required to drive on the left of the road, indicate stops and turns, and carry a red light. Other regulations governed speed, parking and loads.

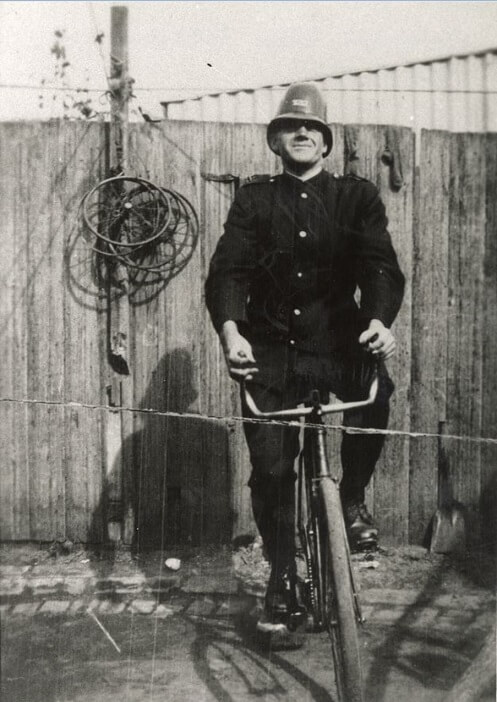

Policemen ― on foot, horse or bicycle ― found it almost impossible to catch speeding drivers. ‘They simply smile at us as they rattle by and we cannot catch them’, one policeman observed. Even if the culprit was brought to court, ‘magistrates were often more sympathetic to well-spoken fellow members of the motoring middle class than to bumbling police officers.’

A policeman directs traffic at the intersection of Elizabeth and Collins streets in the city, 1916

Photograph by Greenham Studios

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

Prior to the 1930s hand signalling by traffic police was the only form of traffic management.

Collins Street, Melbourne, c.1935

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

In 1926 automobiles comprised only half of all traffic in the city. By 1947 they made up more than 90 per cent. Parking problems in the 1930s saw the first multi-level car park (in Australia) built in Russell Street (1938). Kerbside parking was free in Melbourne until the introduction of parking meters in the 1950s.

Mid-century Melbourne

In 1943 Australians were asked to rank their goals and aspirations for the postwar period. Jobs came in first, followed by better housing. Then came a new car. (Morgan Gallup Poll, 30 January 1943, cited in Graeme Davison, Car Wars: How the Car won our hearts and conquered our cities, Allen & Unwin, Melbourne, 2004.)

In 1945 there was one car for every 14 Victorians. By 1953 there was one for every five. By 1969, it was down to one in three. Within a generation, the motor car moved from being a preserve of the wealthy, to being within the reach of ordinary working families.

Australia’s Own Car

THE HOLDEN is assuredly Australia’s own car, embodying the finest in engineering skill, artistic design and compact luxury. It has undoubtedly captivated Australia.

Examiner, 7 October 1950

Most of the cars on Melbourne's roads in the 1940s were run-down, small English-made saloons. Motorcycles (much cheaper than cars) were popular with workingmen, sometimes with a sidecar for the family. This all changed when General Motors-Holden began production of its new Holden sedan.

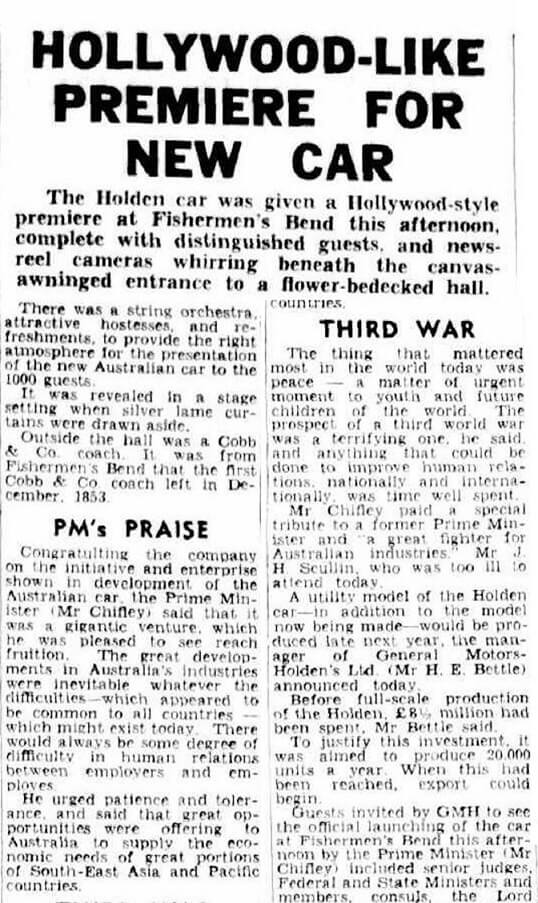

The Holden 48-215, also known as the ‘Holden FX’, was the first car to be manufactured wholly in Australia. Unveiled by Prime Minister Ben Chifley at a launch at General Motors-Holden in Melbourne on 29 November 1948, it was dubbed ‘Australia’s Own Car’. And it was an instant hit. Production began at the rate of 10 cars per day, with a planned annual target of 20,000 units. By 1950 Holden was making 80 cars per day, with a ‘waiting list that ran to 40,000 cars or two years’ production’.

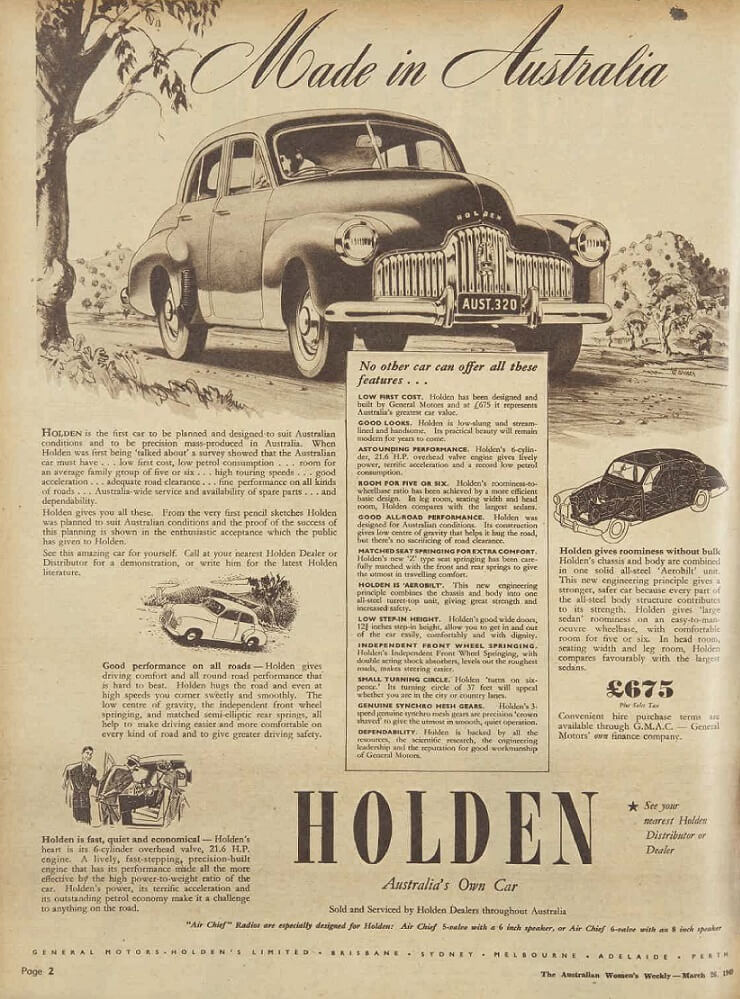

A simple, six-cylinder sedan, the FX was sturdy, reliable and perfect for rough Australian roads, many of them still not sealed. It was roomy and could comfortably fit five, perfect for the 1950s Australian family. (The average number of children in the Australian family unit had expanded from 2.36 children in 1945 to 2.71 a decade later.) And it was more affordable than most cars. The FX sold for £675. With insurance and registration, the on-road cost was about £760: a new model English car cost £1,000.

Middle-class, middle-aged males were overrepresented among new car owners. In the 1950s professional, managerial and small businessmen comprised about 33 per cent of new Holden owners (though only 16 per cent of the polled population), while white-collar workers (22 per cent of new Holden owners) were represented approximately in proportion to the poll sample (23 per cent). Semi-skilled and unskilled workers half as likely (10 per cent of new owners and 22 per cent of the workforce) to buy a new model of ‘Australia’s Own Car’. Only 10 per cent of the new owners were under 30 and 22 per cent over 50. Only one in twenty was a female. (Statistics courtesy Graeme Davison, Car Wars: How the car won our heart and conquered our cities, Allen & Unwin, Melbourne, 2004.)

Prime Minister Ben Chifley at the launch of the first Holden car at the Fishermans Bend factory in Melbourne, 1948

Reproduced courtesy National Archives of Australia

The launch of the new Holden was a fancy affair, complete with distinguished guests and news-reel cameras. According to reports there were flowers, a string orchestra, even ‘attractive hostesses’ with refreshments. Prime Minister Chifley praised GMH for their ‘initiative and enterprise’ in what had been ‘a gigantic venture’.

‘These independent petrol consumption tests prove that … HOLDEN IS WORTH WAITING FOR’.

Advertisement for the Holden FX, The Australian Women’s Weekly, 11 June 1949

Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia

Holden designed the FX to suit local needs and tastes ― tough and reliable, and fuel efficient. Early advertising like this emphasised the economy of the FX.

‘Convenient hire purchase terms are available…’ ― Advertisement for Holden, The Australian Women’s Weekly, 26 March 1949. Hire-purchase allowed the purchaser to take possession of goods immediately, with a deposit of no more than 10 or 20 per cent, and payments spread over several years

Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia

In the 1950s our modern-day consumer credit landscape emerged. Instalment credit was used for car purchases and large household goods, such as refrigerators and radios. By the late-1950s almost 40 per cent of new cars were purchased on terms.

This 48-215 was built in October 1950 at Fishermans Bend and purchased new in November 1950 by Mr Arthur Henry Shelton of Ripponlea in Victoria. Mr Shelton took great pride in his car ― ‘If it rained while he was out, he would dry the car when he came home and it was always covered even in the garage’. Family holidays to Sydney, Adelaide and Queensland were taken in the car.

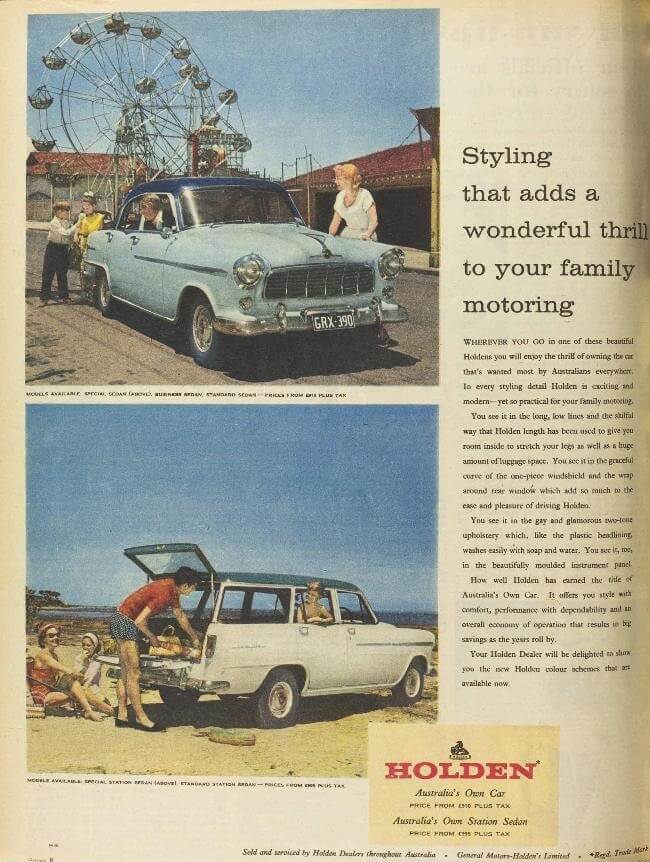

The FJ Holden came on the market in 1953. Referred to as the ‘New Look’ Holden, the FJ was essentially a newer, shinier version of the FX.

The FJ was reasonably priced (from £870) and sold well, becoming ― like the 48-215 ― the first car many families ever owned. There was a range of models available: the Standard, Special, business sedan, utility or panel van.

The FJ was the first Holden to be exported, to more than 15 countries, including Greece, South Africa, Lebanon, Bahrain, Iraq, Nigeria, Saudi Arabia, Pakistan, Jamaica, Tahiti and Hong Kong.

For a comprehensive history of the 48-215 (FX) and FJ, see Peter Robinson, ‘Holden in Australia', The Bulletin, 22 March 1975.

‘Having wheels’

By 1958 Holden accounted for 40 per cent of all car sales in Australia. Ford expanded in Geelong, while Volkswagon manufactured its popular ‘Beetle’ model at Clayton. Toyota also established a plant in Victoria in 1963, initially in Port Melbourne, but later at Altona.

Melbourne became the car manufacturing capital of Australia. And car prices, relative to other consumer goods, began to fall. By 1962 the proportion of Australians who owned a car was one in three and rising. Read more about the motor car industry in Victoria.

The car promised families a new mobility. For the first time it was easy to visit relatives or friends, go to sporting events, or take a trip to the beach.

Guesthouses, with their regimented dinner times and organised games, also began to disappear in favour of caravan parks and camping grounds as people chose to go on holiday whenever and wherever they liked.

Australian Women’s Weekly, 19 February 1958

Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia

Advertisements like this one emphasised the new mobility of the Australian family, courtesy of the motor car. Family holidays, trips to the beach, picnics, or even just a Sunday drive, were all new and exciting possibilities offered by car ownership.

Of course, not all families could afford a car. In the 1960s:

… owning a car was largely an economic matter: while two-thirds of low-income households were still carless, scarcely one-tenth of high-income earners ―the 18 per cent of households earning over $5,000 ―had no car and 43 per cent had two or more. In working-class Collingwood, Fitzroy and Richmond half the households earned less than $2,500 per annum and less than 30 per cent owned cars, while in middle-class Camberwell, Box Hill and Doncaster scarcely a quarter of households earned less than $2,500 per annum and more than 75 per cent owned cars.

Dad usually drove, but mum might have a licence and ‘borrow’ the car for shopping or important social occasions.

From the 1950s annual caravanning holidays became part of the country’s cultural norm. This photograph shows the Bunting family on holiday in Sorento, circa 1958 — their one and only caravanning holiday. According to one of the children, Jane, ‘the kids had a great time, but my mother Shirley didn't enjoy it much.’

Reproduced courtesy Ron Bunting, Museums Victoria

Richard and Jean Hayes bought this ‘Skyline’ caravan in 1957 for 183 pounds. Inside it has one double, and one single bed; an annex provided a second room. Initial holidays were to the Rosebud foreshore, although later the family ― consisting of two adults and four children (Barbara, Graeme, Ian and Linda) ― travelled to Lakes Entrance, Wilson's Promontory, Bright, Shepparton, Mildura, Swan Hill, Mount Gambier, Adelaide, and parts of New South Wales and Queensland. The caravan was towed over the years by three cars: a Vanguard, an HR Holden, and finally a Holden Torana. Read more about the Hayes family caravan at Museums Victoria.

Papadimitropoulos family picnic, Greenvale Reservoir, 1978

Reproduced courtesy Dimitra Birthisel, Museums Victoria

With the car, family picnics could take place further from home. For the Papadimitropoulos family, picnics were an all-day affair, and they would leave the house at 6am to get the perfect tree to sit under. The extended family would cram into three or four vehicles towing a trailer to carry the spit roast. The spit was hooked up to a blue car battery, visible in this photograph. The battery had been modified by one of the uncles to make the rotisserie work. The children were embarrassed by the spit, but it got a mixed response from other picnickers. Read more about the Papadimitropoulos family at Museums Victoria.

In the 1950s about one in ten women held a licence. By 1961 one licence-holder in three was a woman.

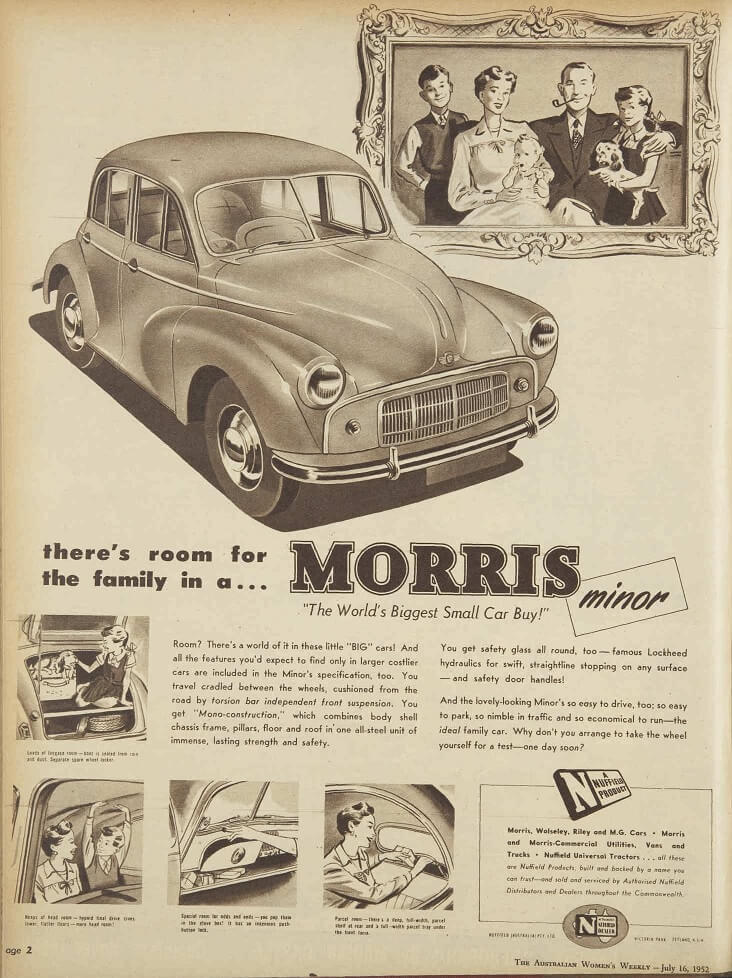

The ’woman driver’ appears here in an advertisement for the Morris Minor in the Australian Women’s Weekly in 1952, albeit subtly. A woman’s hand reaches from the driver’s seat to the glove box.

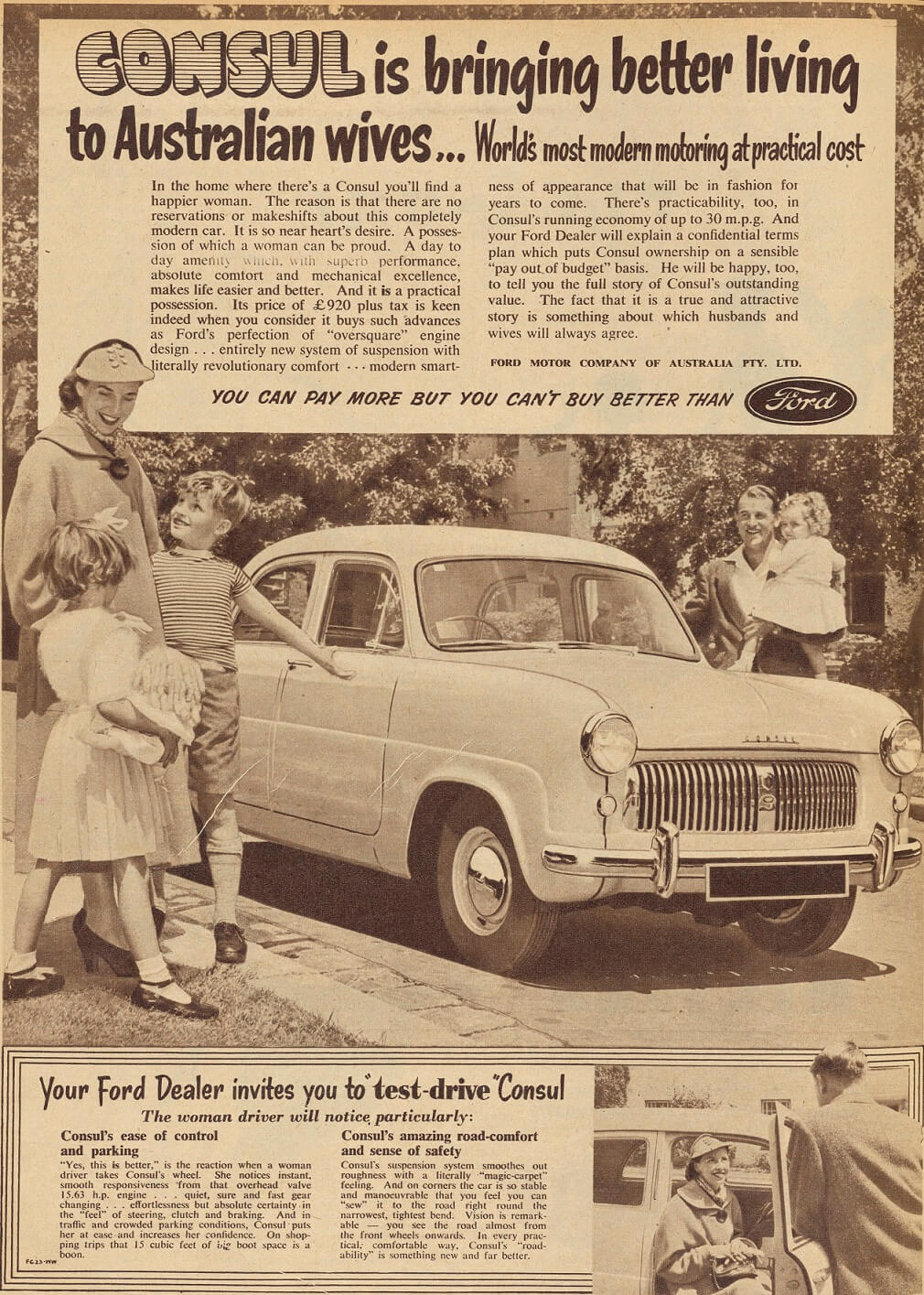

Manufacturers soon recognised the growing influence of the woman driver. ‘Once the man chose the car and the woman the colour… [but now] many women drive the family car more often than their husbands’, Royalauto magazine wrote in 1964. Women began to feature more in car advertisements, especially those for small, compact cars.

Woman with three girls in front of their Ford 'Prefect', Glen Iris, 1961

Reproduced courtesy Ms Margaret Swan, Museums Victoria

For women the incentive to buy a car was particularly strong. Daily shopping was hard work with children in tow. Between 1968 and 1972 new female licence-holders almost equalled males.

Suburban sprawl

The car brought a new sense of time and space to the city. It reinforced the suburban sprawl that had been a feature of Australian cities since colonial times. It reshaped the suburbs, pushing their perimeter out beyond the rim of mountains and far along the coastline, filling in the gaps between the rail and tram lines, transforming the regular oscillation of commuters from city to suburb into a more complex web of movements across the metropolis. It created a new engineering, a new architecture, a new aesthetic.

Graeme Davison, Car Wars: How the car won our heart and conquered our cities, Allen & Unwin, Melbourne, 2004

As post-war Melbourne’s population grew — from 2.3 million in 1951, to 2.9 million in 1961 and then 3.5 million in 1971 — the inner suburbs became increasingly crowded. Factories looking to invest in new, larger, production machinery had no room to expand, while congested inner-suburban streets made transport difficult. Industry began to look to ‘greenfield’ sites on the margins of the city. General Motors-Holden moved to Dandenong in 1952 and was followed by several of its major component manufacturers and competitors like Volkswagon. Ford also chose to relocate, but moved north to Broadmeadows.

For decades factory workers had lived close to their workshops. But once the factories relocated to Melbourne’s margins, the distances were simply too great. Industrial workers followed the factories, and new suburban development mushroomed in Melbourne’s outer ring. Most of these new estates were poorly served by public transport, making families entirely dependent on the car.

General Motors-Holden, Dandenong plant, c. 1964

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria. Photograph by Wolfgang Sievers.

In 1951 only 15 per cent of Melbourne workers travelled to work by car. By the early 1970s almost two-thirds of Melbourne workers travelled to work by car.

Huge road systems were built to move the workers (quickly) from home to work. Large workers’ car parks were provided beside factory buildings.

A ‘drive-in’ city

In the modern world the miracles of one day are mundane the next — think of the Internet or the mobile phone. Today cars are so ubiquitous they are almost invisible. But there was a moment, only yesterday in historical time, when these thrilling new machines transformed Melbourne and Australia; when, without anyone particularly noticing, they tore up the old world and created a new one.

‘The Cars that ate Melbourne’, The Age

As Graeme Davison has explained the motor car ushered in new urban forms ― the freeway, multi-level car park, roadside diner and service station. Cars changed the look of the family home. Front gardens were stripped of foliage to make way for concrete driveways and carports. On new suburban estates, streets curved into crescents and cul-de-sacs to slow the speed of cars. The car changed the way Melburnians shopped. Small businesses in inner city neighbourhoods were increasingly replaced by sprawling shopping malls in the new outer suburbs.

Australia’s first ‘drive-in’ shopping centre was built at Chadstone in 1960. The centre, which comprised more than 85 shops and a large Myer department store, represented a new scale, and new style, of retailing. The Herald reported: ‘Mrs Suburbia can drive into the centre after the morning peak hour with her under-school-age children and family dog.’ Parking spaces were angled at 45 degrees, so ‘that women will be able to park easily. There will be no embarrassing manoeuvres into small spaces.’ A children’s playground and child-are facilities were some of the facilities offered to mothers.

Increasing car ownership saw the emergence of new tourism buildings, most notably the motel. By 1960 Australia had more than 80 motels, with a further 80 under construction.

Motels had all the ‘mod cons’, such as air-conditioning and a bathroom, and were affordable for families. Guests could park outside their room, making transport of food and luggage easy.

Australia’s first drive-in theatre opened in Burwood in July 1954. Two years later, Australia’s first twin drive-in, the Metro, opened in Clayton. With room to accommodate 1,500 cars, a ‘superior meals service’ and a baby’s changing room, it was the biggest in the Southern Hemisphere.

Visiting the drive-in became a popular family outing. Kids could come in their pyjamas and lie on the back seat with some blankets and pillows. Dad could purchase hamburgers and hot-dogs at the café for barbequing.

The ‘drive-in’, it was reported, ‘appeals to a different audience from that of the indoor theatres.’ It was more relaxed: ‘You can talk, smoke, chew peanuts, eat sandwiches, and nobody cares a hoot’!

‘My first car’

Most people will remember their first car — the colour, the make, any idiosyncrasies it might have had. I certainly do. My first car was a 1983 Ford Laser, crimson red with leather interior. And boy did it have some quirks. Only the passenger side window opened, and the doors stuck in summer. It had a choke — yes, millennials, a choke — and was slow to start on a cold winter morning. It would overheat easily, and I would plan my lectures at Monash University outside peak-hour traffic. Anything between 10 and 3pm was generally O.K.

But oh, how I loved this car. I was the first of my friendship group to have a car and ‘Larry the Laser’ served us all faithfully. Nights out, interstate holidays, trips home to stock up on food and clean clothes — Larry did it all, albeit temperamentally at times.

A (small) note on ‘gender’.

Do you name your car? Does it have a gender? According to one study in 2014 women under the age of 25 are most likely to ‘name’ their cars. The car is usually female and one in four names begin with a ‘B’. Baby, Betsy, Bessie, Black Beauty and Betty are the top five. Outside this age group about one in five drivers name their cars. Women (23 per cent) are more likely to do so than men (18 per cent).

According to the study about 50 per cent of drivers assign a gender to their vehicle. More women consider their car ‘female’ (88 per cent), than men (55 per cent).

I apparently bucked the norm by calling my car ‘Larry’. I don’t remember thinking particularly about gender, more that I liked the alliteration and the way it rolled off my tongue. I can report, however, that I have returned to trend. In our family we have two cars and we have named them both. The newer black one has the rather racy moniker, ‘Trixie’, while the sturdy, dependable (and yes, much older) family Holden is called ‘Pearl’.

We asked staff and volunteers at the Old Treasury Building to contribute memories of their first car. Here are just some of them.

Richard:

My first car was a Honda Z, basically a Honda motorcycle, but with four wheels. It red-lined in second gear and was smaller than a mini. It was deep purple and brand new was $1500 on the road. I had it right through my university years and often went up and down the highway between Ballarat and Canberra. My greatest memory of the car was transporting four rowers in it from the ANU boatshed to the regatta course near the Governor's house. They just squeezed in and then put their arms out the window so that they could transport four oars as well.

Deb:

Our first car was a Ford Anglia circa 1950. It was bright red with a grey canvas roof. It was a two-door, with bucket seats at the front. It wasn't particularly waterproof as the windows had canvass flaps that used to flap around in the breeze and let water in! It was stinking hot in summer and freezing cold in winter. The car was bought second hand around the late 1950s or early 60s. I was only about 5 or younger when we got it. My sister was a baby and used to be carried in mum's arms in the front seat until she was a toddler and graduated to the back seat.

I remember going shopping on a Saturday morning to Bentleigh shopping centre for provisions with mum, dad and my sister. Known as the "big shop" in my family, it paled a bit for us kids and we were often left in the car while mum and dad went to the grocery store, our last and most boring stop. Once my sister and I had a fight over an umbrella and one of us stuck it in the roof creating a hole. Boy, did we get into huge trouble. For what seemed forever my mother used to point to the patch, give us the side eye and shake her head.

We used to go to Tootgarook taking a cousin with us. We three girls were piled into the back, often with luggage and groceries at our feet. There were no seat belts and every time we went round a curve or a corner we used to slide across the back seat squashing one of us against the window We used to beg dad to go to Arthur's Seat. There was a lot of giggling and squealing and my little sister, who was in the middle, was thoroughly squished. She was the first to yell “Go faster daddy" when there was a curve, however.

We also drove to Avenel, near Seymour where our relatives had a farm. We had to go over Pretty Sally: the car used to strain to make it in 2nd gear. Dad used to yell "push" and my sister and I would stand up and push against the front seat as hard as we could.

I also remember dad used to pick me up from Sunday school on hot days. He used to take our dog Scamp in the front seat. The dog used to sit with his nose or half of his body sticking out of the flap. I used to watch for him and was often treated to the sight of Scamp falling out of the window flap as the car made a right-hand turn from Centre Rd to Mackie Rd. Dad used to stop the car, open the left-hand side door, yell "come here, you silly mutt" and they'd continue on their way.

Strangely I cannot remember them ever having the roof down. I can remember that the windows could come out.

Frances:

Our first car was a 1930 Dodge. No-one else in our street had anything like this. It was big, clunky and classified as a veteran car even back in the 60s.

Coming from a family of five children (eventually five became seven) under the age of five, it was no armchair ride for my parents and for many years we did not have a family car, as it was difficult to buy a car that would seat seven people let alone nine.

The Dodge was purchased from a family friend and came complete with running board, leather seats and flickers. (We call them indicators now.)

All five of us would be seated in the back seat, mum would often hold one of the little ones on her lap. Of course, in the 1960s there were no such things as seatbelts.

When my youngest sister and brother came into the world, we would take two kitchen stools from the house and place them in the back seat of the Dodge to accommodate all seven children and two adults.

We later upgraded to a 1935 Pontiac, a slightly bigger and roomier car. In 1972, we finally bought a more modern car — a1965 Valiant station wagon. What a luxury that was.

Family outings were quite stressful for my parents, one of us, sometimes two or three, would invariably get car sick, the old cars would overheat, and dad would get lost somewhere on a country drive.

As a child I was quite shocked when on a day outing to Darraweit Guim, my father used the swear word “Bugger” (due to burning his hand when he tried to open the overheated radiator) Much to my mother’s shock and horror, she castigated him for swearing in front of the children. Poor dad.

Of course, family holidays to Rosebud or Tootgarook were taken annually during the Christmas holiday. Imagine how much fun we had all crammed in the car with suitcases often placed on the roof rack of the car. This would have also been a comedic sight for onlooking traffic.

During long trips, my father invented a game called “lands” where we would all freeze in the positions we land in when he turned a corner or rounded a sharp bend in the road. This kept us all amused during long drives, and probably accounted for the frequent attacks of car sickness.

It comes as no surprise that family outings/holidays were kept to a minimum. Looking back now it seems ludicrous that we were able to get away with these practices, but back then, they were very different times, and have provided many great memories for a child growing up in the 60s.

Gabrielle- ‘Arthur’:

It was 1956. I was five or six years old, and my father came home with our first car. It was a cream FJ Holden, Registration GNH881. There were four children in the family ― myself, my sister Pauline, my brothers John (later Jack) and Bernard (later Bernie) ― and we all hopped into the car to go for our first drive.

My father was never the best driver and on this, our inaugural trip, he drove up to Bluff Road (we lived in Hampton). Driving along Bluff Road he ran into a bus shelter, which completely collapsed. There was not a mark on the car and it was, admittedly, a pretty wonky shelter. But the old FJs were very sturdily built. For years, I wondered if I had imagined this incident, which of course we all found hilarious, but when talking to Jack some years back he stopped and roared laughing. He had forgotten, but my telling the tale jogged his memory.

The car became an integral part of our family life, but never more so than in 1959 when we did a family trip to see my aunt (my father’s sister) and family in Brisbane.

This was the only real family holiday we ever had. We did spend some weeks at Anglesea over the summer, but this was a long trip.

We travelled slowly, stopping to stay at motels on the way and it probably took us about a week or ten days to get to Brisbane. I remember going to Yass, Forbes and Gundagai. We also went to Canberra and Sydney. My father particularly wanted to visit Canberra as he had never been there and had an intuitive love of Australian political history.

Every day had its moments. Because there were four children, one of us had to take turns sitting in the middle of the front seat. It seemed that every day that child, or one of us, was sick. My father, as I said not the best driver, had a habit of making the wrong turns at every possible occasion. We would, of course, all have our say in the matter, which became quite hilarious. In both Sydney and Brisbane, he drove the wrong way down the one-way streets, with us all again offering suggestions and advice. My mother always said she wished she had another adult to enjoy the adventures with.

We eventually arrived in Brisbane, visited my Aunt Madge and her family and then went to Coolangatta for a week or two. The drive home was as epic as the drive up, with similar adventures. I was probably nine at the time, but I have clear fond memories of much of this holiday.

Eventually the car had a facelift and became a two-tone grey. I’m not sure why, but it probably gave it a new lease of life.

Then, in about 1966, my father got a new car, a new blue and silver Ford Falcon. My brother Jack, who was now 18, inherited the car and this is when it became known as Arthur. It was named after Arthur Calwell, the Labor Party Leader. The Ford Falcon was called Gough, of course after Gough Whitlam. My father (Frank) was the Manager of the Catholic Worker and a very strong Labor man, in the times when the DLP reigned in Catholic circles. Our family life involved many political discussions and my father continued to be both a member of his Union and the ALP. He started life as a boilermaker, but then became full time Manager of the Worker, until it was banned by Dr. Mannix, the Archbishop of Melbourne, after the split in 1955. He was able to move into a new business, with the help of friends, but continued to manage the Worker until he died. So naming the cars after Labor Party leaders was inevitable. That’s how we had Arthur, the old battler, and the new flash Gough.

In the early 70’s Jack sold Arthur and he vanished, but after that, every time I saw an FJ Holden, I always checked the registration to see if it was Arthur. I think we all did, but he was never seen again. That is why I can remember the Registration number, GNH 881.

Doug- ‘Primary school and our quirky REO truck’:

In the 1960’s my family lived on a farm seven miles from a small town in western Victoria where I went to primary school with my sister. Normally we caught the school bus from our front gate, each trip approximately 25 miles through rolling hills and tableland country with large redgum trees, sheep and cattle. But occasionally our dad would pick us up from school either in our car or, on special occasions, in his old, dark green REO truck.

The REO was somewhat quirky, often being difficult to start and steer, and having the tendency to overheat in warmer weather. Nevertheless, seeing the REO parked outside our school’s front gate was particularly exciting because, not only did it shorten the trip home considerably, but it gave us kids a bird’s eye view of the countryside. We all sat in the front together on the long, weathered, torn seat, happily chatting above the roar of the engine as the big truck lurched home with dad wrestling with the steering wheel and gear stick.

Sometimes we were allowed to buy an icy cold chocolate milkshake at the local milk bar before dad pointed the REO towards home. If we were particularly hungry we skipped the milkshakes and instead bought two shillings worth of hot, chunky, salty chips or potato cakes, wrapped in white butchers’ paper from the fish and chip shop next door to the milk bar. Absolutely delicious!

Unfortunately ― and much to my embarrassment ― a couple of times right outside the front of the school gates the REO refused to start, instead making a deep, grinding noise. Dad would then pull up the bonnet and tinker with various parts of the engine with a spanner in hand, watched by my curious school friends. Eventually the engine would start, accompanied by a large belch of smoke and nods of approval from the onlookers.

One very hot summer afternoon Dad and I were heading home from school in the REO when he shouted “#!@#, I think we may have a problem” and pointed to the temperature gauge. We turned the corner on to the gravel road leading up to our farm. Halfway up a steep incline steam started pouring from the REO’s radiator. Dad put the REO into reverse and then slowly backed down the hill, stopping opposite a dam in our next door neighbour’s paddock. He then jumped out of the cabin, grabbing an old bucket from the cabin floor, climbed the fence, and waded into the dam fully clothed and filled the bucket with water. I also managed to climb the fence and jump into the dam wearing only my school shorts, eager to cool down from the ferocious heat.

Dad took some time to get the radiator cap off safely and top up the REO with the dam water so that we could get home. Whilst he did, I squelched around in the muddy dam, gasping with surprise about how cold the water was and secretly hoping that there were no tiger snakes around and that Dad wouldn’t get the REO going too quickly.

Much to our disappointment, Dad “retired” the REO soon after, considering it too unreliable for the school run, let alone for carting wood, hay and wool bales.

Further Reading

Some excellent (and more comprehensive) histories on early motoring in Melbourne and the Motor Acts are:

Graeme Davison, Car Wars: How the car won our heart and conquered our cities, Allen & Unwin, Melbourne, 2004

Kieran Tranter, ‘The History of the Haste-Wagons’: The Motor Car Act 1909 (Vic), Emergent Technology and the Call for Law.

Rick Clapton, ‘Keeping Order: Motor-Car Regulation and the Defeat of Victoria’s 1905 Motor-Car Bill’, Provenance: The Journal of Public Record Office Victoria, Issue no. 3, 2004.

John Schauble, ‘Young Men in a Hurry – How a Cyclist’s Death Defined Early Motoring in Victoria, Victorian Historical Journal, Volume 92, Number 1, June 2021

Other sources:

Charles Pickett, editor, Cars and Culture: Our Driving Passions, Powerhouse Publishing and HarperCollins, Sydney, 1998

Don Garden, Victoria: A History, Thomas Nelson Australia, Melbourne, 1984

Glenn Jessop, ‘Victoria’s Unique Approach to Road Safety: A History of Government Regulation’, Australian Journal of Politics & History, Volume 55, Issue 2, June 2009, pp. 157-315

Graeme Davison, Car Wars: How the car won our heart and conquered our cities, Allen & Unwin, Melbourne, 2004

John Schauble, ‘Young Men in a Hurry – How a Cyclist’s Death Defined Early Motoring in Victoria, Victorian Historical Journal, Volume 92, Number 1, June 2021

Kieran Tranter, ‘The History of the Haste-Wagons’: The Motor Car Act 1909 (Vic), Emergent Technology and the Call for Law

Rick Clapton, ‘Keeping Order: Motor-Car Regulation and the Defeat of Victoria’s 1905 Motor-Car Bill’, Provenance: The Journal of Public Record Office Victoria, Issue no. 3, 2004

Tony Dingle, Settling, Fairfax, Syme & Weldon Associates, McMahons Point, NSW, 1984

Online resources

‘A history of Holden in Australia ― Timeline’, The Guardian

‘A Need to Travel: 1901-1917’, Department of Finance

‘Australia’s own car', State Library Victoria Blog

‘Australia’s Six motor car’, National Museum Australia

Motor Cars, entry in Encyclopedia of Melbourne

‘The Cars that ate Melbourne’, The Age

‘Holden launch’, National Museum Australia

‘Holden Prototype No. 1’, National Museum Australia

Josh Alston, ‘The Story of Australia’s first car’, Drive

‘Women more likely to give their car a nickname’, 2014, The Globe and Mail