‘I think it was the most marvellous thing that has ever been invented’, unnamed Melbourne woman, interviewed late 1990s

The oral contraceptive pill, usually called simply ‘the Pill’, was released in Australia in early 1961, after its launch in the United States in the previous year. It offered reliable contraception, without mechanical intervention or messy chemicals, and allowed women to engage in sexual activity without fear of pregnancy. For the first time sexual fulfilment became a realistic goal for women as well as men, and in time the Pill would help to transform sexual relations both within marriage and in society more generally.

The Pill contained synthetic hormones which suppressed ovulation and was available only on prescription from a medical practitioner. At first it was also expensive. In early 1961 the retail price of one month’s supply was £2/3/9, which amounted to about ten per cent of the minimum monthly wage. This placed it beyond the reach of many working-class women. But the cost fell rapidly. By 1964 the cost of a month’s supply had fallen to about £1, and usage quickly increased. By the 1970s Australian women were the largest per capita users of the Pill in the world.

The ‘Swinging Sixties’

Sexual attitudes were changing rapidly at this time. The decade of the 1960s has been described as the ‘Swinging Sixties’, with increased sexual experimentation outside marriage, and the advent of the Pill is sometimes linked to these significant social changes. In time that might well have been the case, but initially most doctors were only prepared to prescribe the Pill to married women. Medical clinics on university campuses sometimes took a more lenient view, but generally it was not until the advent of Family Planning Clinics in the 1970s that the Pill was made more widely available to single women. There is also a good deal of evidence to suggest that single women were often reluctant to approach a doctor to ask for the Pill, since this meant declaring that they were sexually active. Disapproval of sex outside marriage lingered, especially amongst the parents of the Sixties generation.

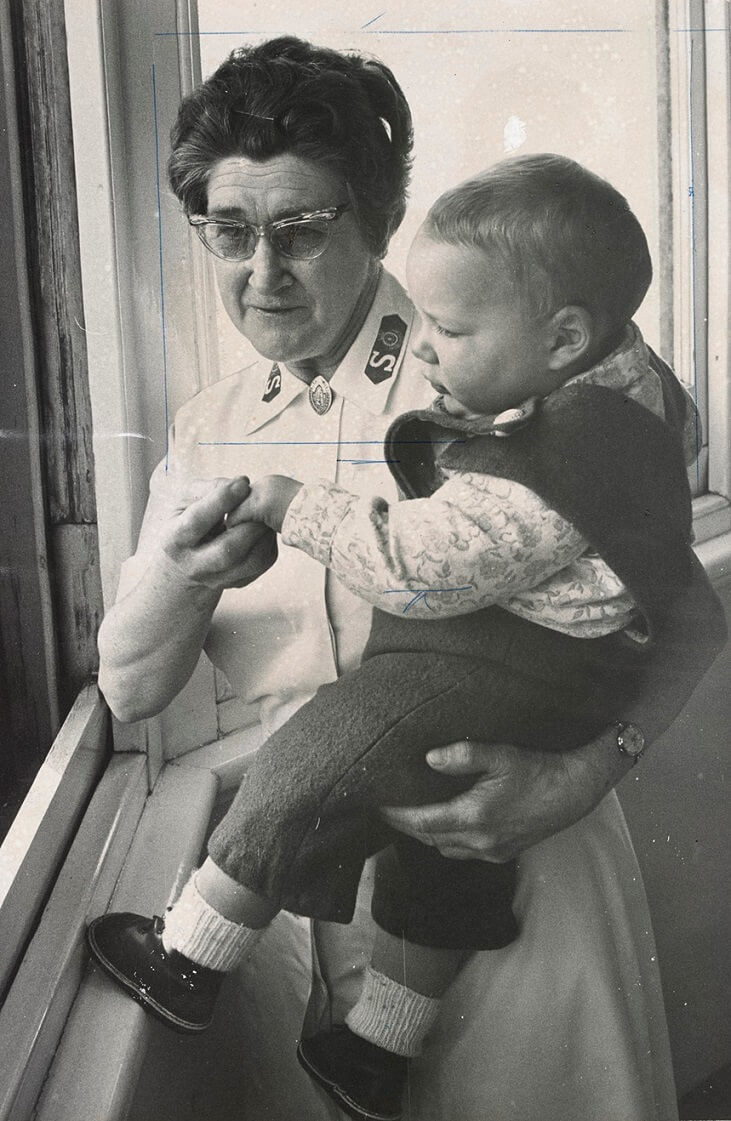

The unfortunate result was many unplanned pregnancies. Demographers have charted a steep rise in the non-marital conception rate in the period from the end of the Second World War until the early 1970s, and an accompanying rise in the number of teenage brides/mothers. The options facing these women were little different in the 1960s from those in earlier decades, despite the changing times. Unless they had the knowledge and the funds to pay for a discreet termination, they faced the prospect of either a swift marriage, a ‘backyard’ abortion, or giving birth, probably in one of the institutions for ‘unmarried mothers’ provided by one of the religious orders. Abortion was a serious criminal offence and doctors faced both a criminal charge and being barred from practice, if they were caught.

If they chose to give birth, these young women almost certainly faced great pressure, from both family and the institution, to surrender the baby for adoption, since there was no financial support available to unwed mothers. There were literally thousands of these so-called ‘forced adoptions’ in the immediate post-war decades, often with tragic consequences for the mother, and sometimes also for her baby. Many relinquishing mothers suffered decades of grief and guilt. It was also a lottery for the babies. Not all found adoptive parents, and the outcome for those who did, varied. Many formed loving relationships with their adoptive parents, but other families struggled to bond with their adopted children. Some of those children then embarked on the difficult journey to locate their birth mothers, with many official obstacles in the way. The pressure on young women to relinquish their babies reduced significantly when the Federal Government made a pension available to non-widowed single mothers in 1973. Despite an initial waiting period of six months from the date of the birth, this benefit made it possible for far more young women to keep their babies. However, the number of such births was already falling in 1973, reflecting the greater availability of reliable contraception and access to legal abortion.

Abortion law reform

Reform of the abortion laws was a growing political issue in the 1960s. Although termination early in a pregnancy in a medical clinic was a relatively quick and safe procedure, backyard and self-induced abortion continued to exact a dreadful toll of young women’s lives. Janet McCalman has described in stark terms the ‘suffering’ that was seen in the surgical wards of the Royal Women’s Hospital in the period before 1970, as doctors did their best to repair the damage caused by both ‘back-yard’ and self-induced abortions. Desperate women syringed their wombs with laundry detergent, disinfectant, copper sulphate or high-pressure hoses. They inserted sticks, knitting needles or umbrella ribs through the cervix, in attempts to force expulsion of the foetus, often causing septicaemia. By the time they presented at the hospital these women were usually desperately ill. The Women’s Hospital could see as many as 20 or 30 such cases each day. Sickened doctors worked alongside feminist organisations to campaign for legalized abortion.

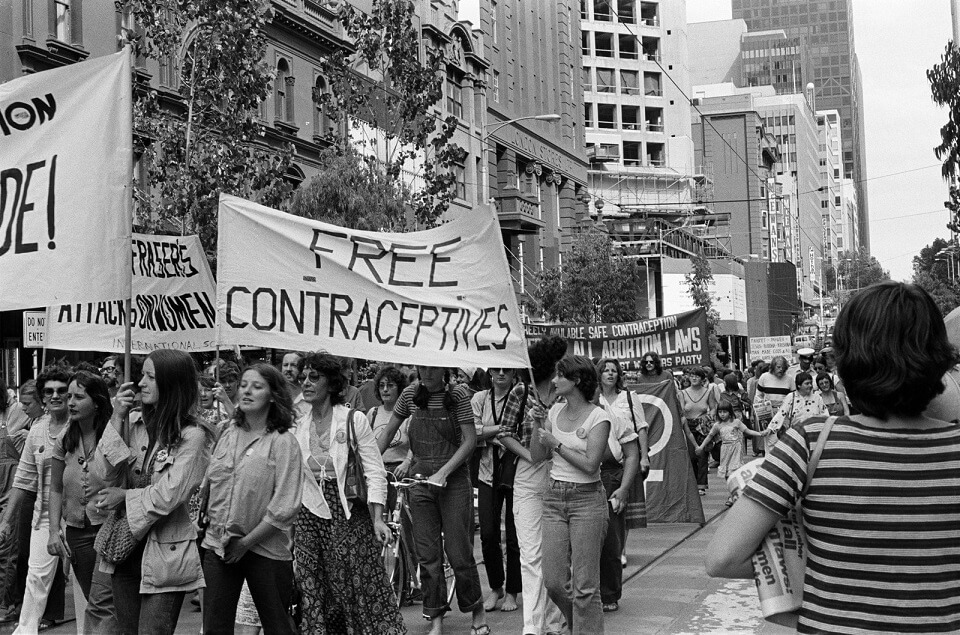

Women’s Liberation march in Melbourne, May 1979

Courtesy State Library Victoria

The placards demanded access to free and safe contraception and abortion.

The breakthrough came in 1969 when in the Victorian Supreme Court hearing into R v Davidson Menhennitt (J) ruled that abortion was justified legally if ‘necessary to preserve the physical or mental health of the woman concerned, provided that the danger involved in the abortion did not outweigh the danger which the abortion was designed to prevent’. It took some years, but by the late-1970s the rate of non-medical abortion was negligible, and the teenage pregnancy rate also fell precipitously.

The Pill and information about contraception

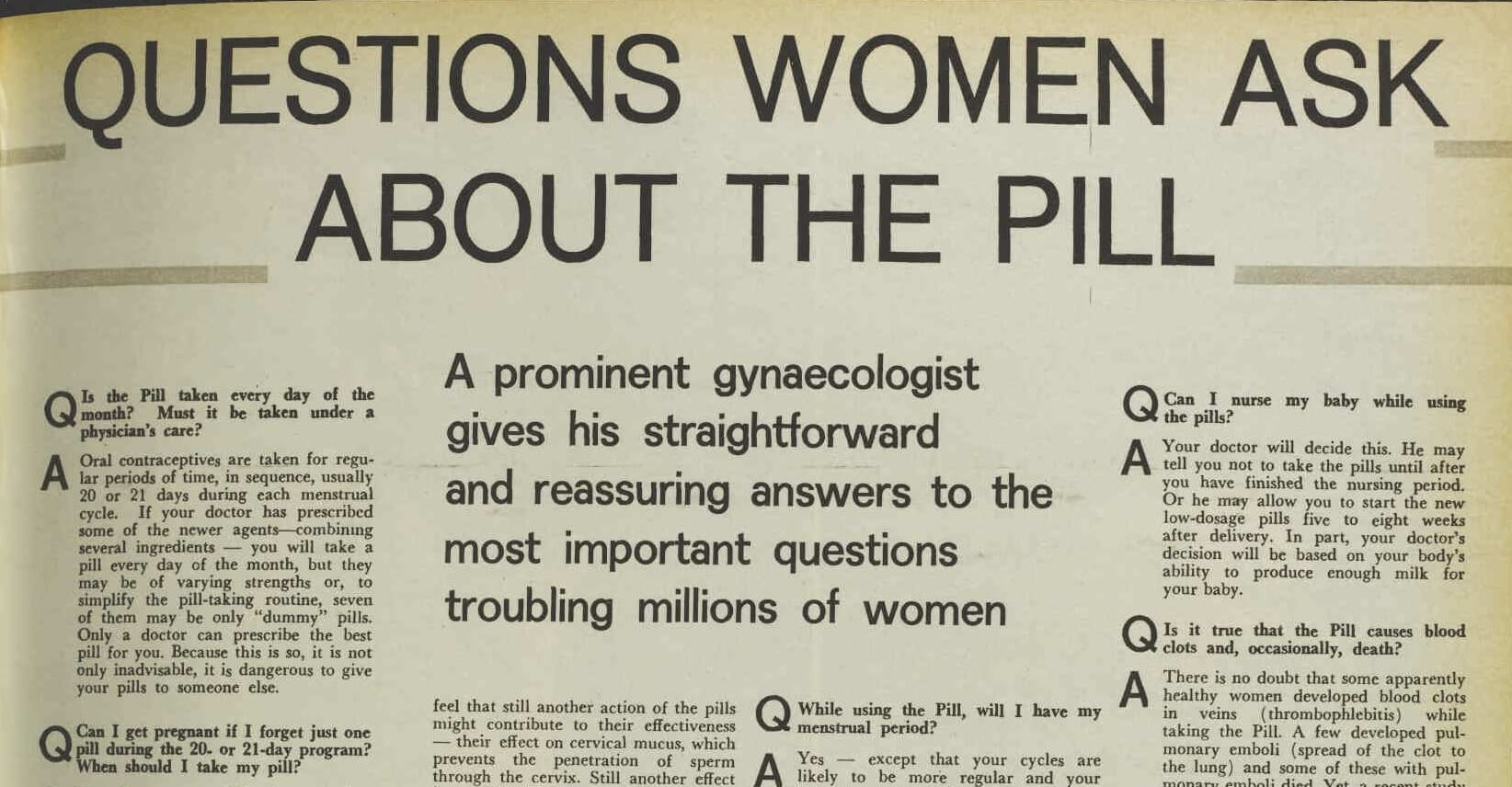

When the Pill was released in Australia in 1961 it was still illegal to advertise any form of contraceptive device outside medical journals— a hangover from earlier attempts to encourage Australian women to have more babies. But the possibilities of the Pill attracted the interest of the general press, which printed many news articles about this new contraceptive, both positive and negative. Women’s magazines were especially important in providing information on the Pill through general articles and interviews with doctors, many of them favourable. Such articles often attempted to address reports of side effects and answer any questions troubling their readers. They were an important source of general information for women.

Australian Women’s Weekly 17 September 1969

National Library of Australia

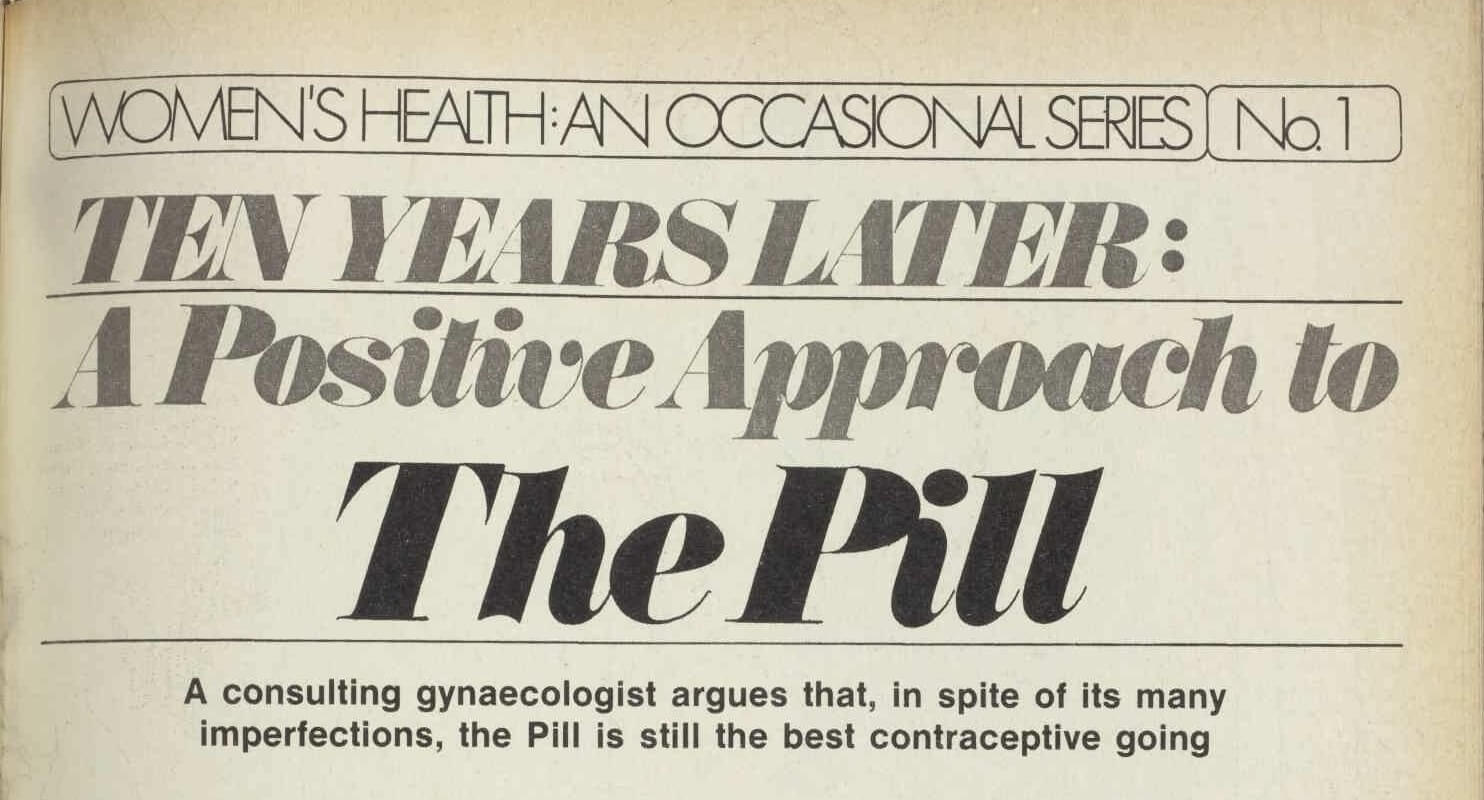

Australian Women’ Weekly 22 October 1975

National Library of Australia

The Pill and family life

The Pill transformed the way in which young people approached marriage and family planning. For the first time reliable contraception made it possible for married women to control their childbearing with confidence, and the reproductive rate fell steadily from the 1960s. From 1976 it was below replacement level (officially estimated to be 2.1 births per woman) and it continued to decline. In 2021 it was 1.7 births per woman. Women could also delay childbearing to choose the time it suited them to start a family, and age at first birth also rose steadily in the late-twentieth century. In 1981 only 15 per cent of first mothers were aged over 30. By 2019 over half had their first child in their thirties, while 17 per cent were aged over 35 (an increase from 5 per cent in 1991). Teenage mothers virtually disappeared, falling from 17 per cent in 1961 to only 4 per cent in 2019.

The Pill was not the only factor in this transformation of family size and shape. Improvements in older forms of contraception, like intra-uterine devices, also made it easier for women and men to plan their families. The early Pill did not suit all women. At first the dose of synthetic oestrogen was quite high, causing unpleasant side-effects in some users. But pharmaceutical companies soon began to produce lower-dose pills, which were equally effective, allowing more women to use them. Debate has also continued over links between use of the Pill and an increased danger of blood clots or stroke. The low-dose pill significantly reduced this risk.

Newer, ‘low dose’ pills like zoely now dominate the market. Contraception continues to improve, with new products, including contraceptive implants, which release small amounts of hormone into the blood stream to inhibit conception, now challenging the Pill in popularity.

Contraception and religion

While most religious groups continued to disapprove of sex before marriage, their attitude to contraception was mixed, with the notable exception of the Roman Catholic Church, which remained adamantly opposed to anything other than the rhythm method. This presented Catholic women with a moral and spiritual dilemma if they wished to use the Pill. Many hoped that the reforms introduced by the Second Vatican Council (1962-65) under Pope John XXIII might see a more liberal approach to contraception, but instead his successor, Pope Paul VI, issued an encyclical in 1968 affirming the ban on all contraception, including the Pill. It caused widespread dissension in the church and many women decided simply to ignore it. Frank Bongiorno argues that this shift amongst Catholics away from the teachings of the church represents a ‘crucial moment in Australian history’. (p.162) He cites a survey in the Australian newspaper in 1970 finding that only a minority of Catholics (29 per cent) supported the papal ban.

Although Catholic women lagged behind others in their adoption of the Pill, many did so eventually. Migrant women were also less likely to use the Pill, although the reasons for this are unclear. Religious belief might have been a factor, or the expense. There may also have been other cultural reasons. There was a long tradition of the use of withdrawal amongst some cultural groups and this may have lingered.

Family life and the Pill

There can be little doubt that access to the Pill allowed women to control their fertility with a degree of certainty not possible before. Family size fell almost immediately, while women were also able to space their children with confidence. But it is possible that the greatest impact of the Pill was on sexual relations within marriage itself. Freed from the ever-present fear of pregnancy, women were able to express themselves sexually for the first time, and that may have removed one of the greatest barriers to marital harmony afflicting earlier generations.

Further reading

Michelle Arrow The Seventies: The personal, the political and the making of modern Australia. New South Books, 2019

Frank Bongiorno, ‘January 1961 The Release of the Pill: Contraceptive Technology and the Sexual Revolution’, in Martin Cotty and David Roberts (eds) Turning Points in Australian History. University of NSW Press, 2008, pp.157-170.

Gordon Carmichael, ‘Non-marital pregnancy and the second demographic transition in Australia in historical perspective’, Demographic Research, Vol. 30, Article 21, 5 March 2014, pp. 609-40.

Janet McCalman Sex and Suffering: Women’s Health and a Women’s Hospital. The Royal Women’s Hospital, Melbourne 1856-1996. Melbourne University Press, 1998.

Marian Quartly, Shurlee Swain and Denise Cuthbert The Market in Babies: Stories of Australian Adoption. Monash University Publishing, 2013.