We expect our refrigerators to keep food fresh and cold, but rarely spare them a second thought. It wasn’t always this way. Before refrigeration, people had to invent clever ways to preserve their food.

This is not a history of the technology behind, or the science of ‘creating cold’. Nor is it a study of the impact of refrigeration on farming and food supply chains, both enormous and enduring. This is a brief (and hopefully somewhat entertaining) look at refrigeration ― or rather, keeping food cool ― in Australian homes from the mid-nineteenth century. How did households keep their milk from going sour, and their butter from melting?

The ‘Coolgardie Safe’

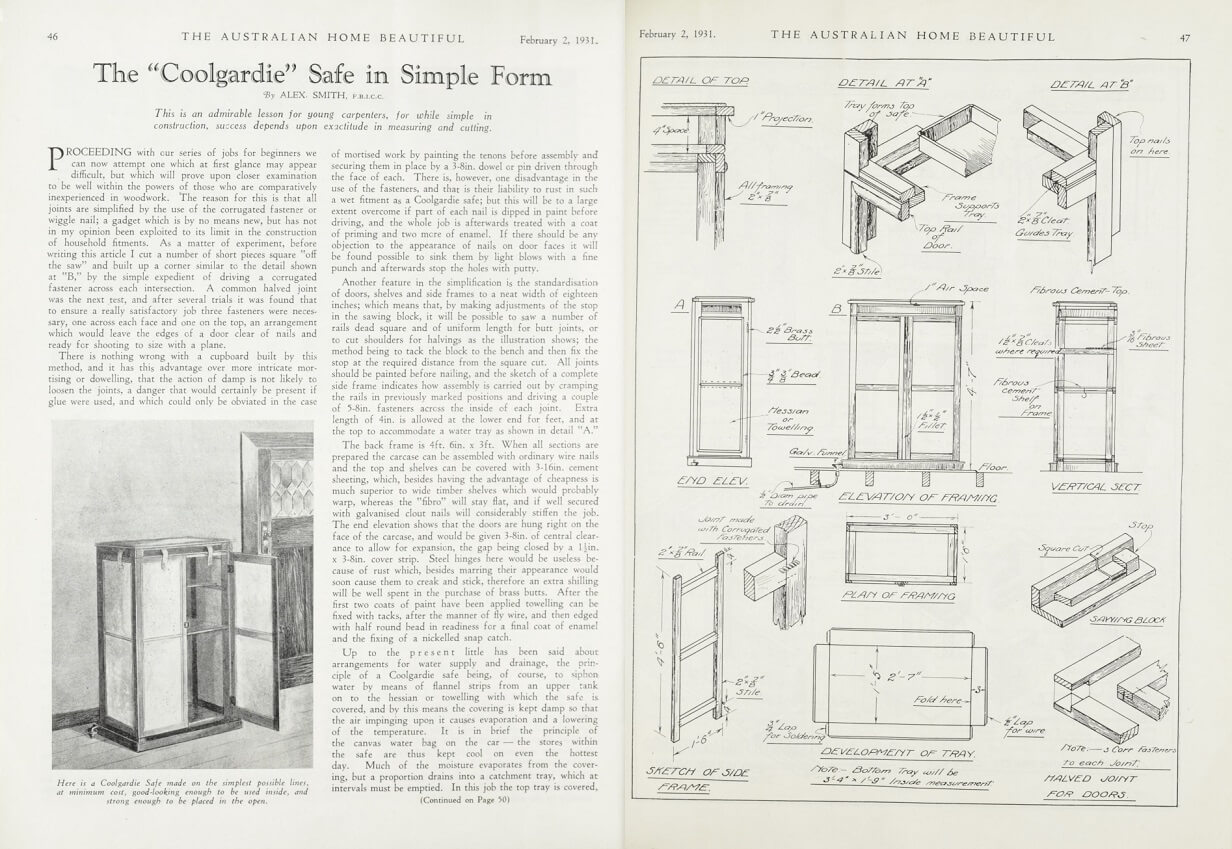

From the late-nineteenth century some Australian households used a ‘Coolgardie safe’ to keep their food fresh. The safe consisted of a timber or metal-framed cabinet with open sides covered in hessian fabric. On top of the cabinet, a tank was filled with water and strips of flannel or felt hung from the tank to the hessian. Through a process of capillary siphoning (wicking), water seeped through the hessian, keeping it damp. The safe was kept on the verandah, or covered way, usually in a direct breeze: as the breeze passed through the wet hessian the fabric absorbed the heat from the surrounding air and kept the safe cool. The safe protected food from flies and scavengers, with the feet placed in a tray of water to deter ants.

It is just a variation of the bushman’s hessian bag hanging in a tree, but whereas that has to be wetted constantly, with this idea of having a tin full of water, it only needs to be filled once or twice in the twenty-four hours. Try it, and you will be surprised at its success.

Table Talk, 11 January 1912

The Weekly Times claimed that the Coolgardie Safe was a ‘boon to womenfolk’, but fresh food was still needed daily, even twice daily in the summer months. A constant supply of water was also required: about eight gallons (over 30 litres) of water was used every 24 hours.

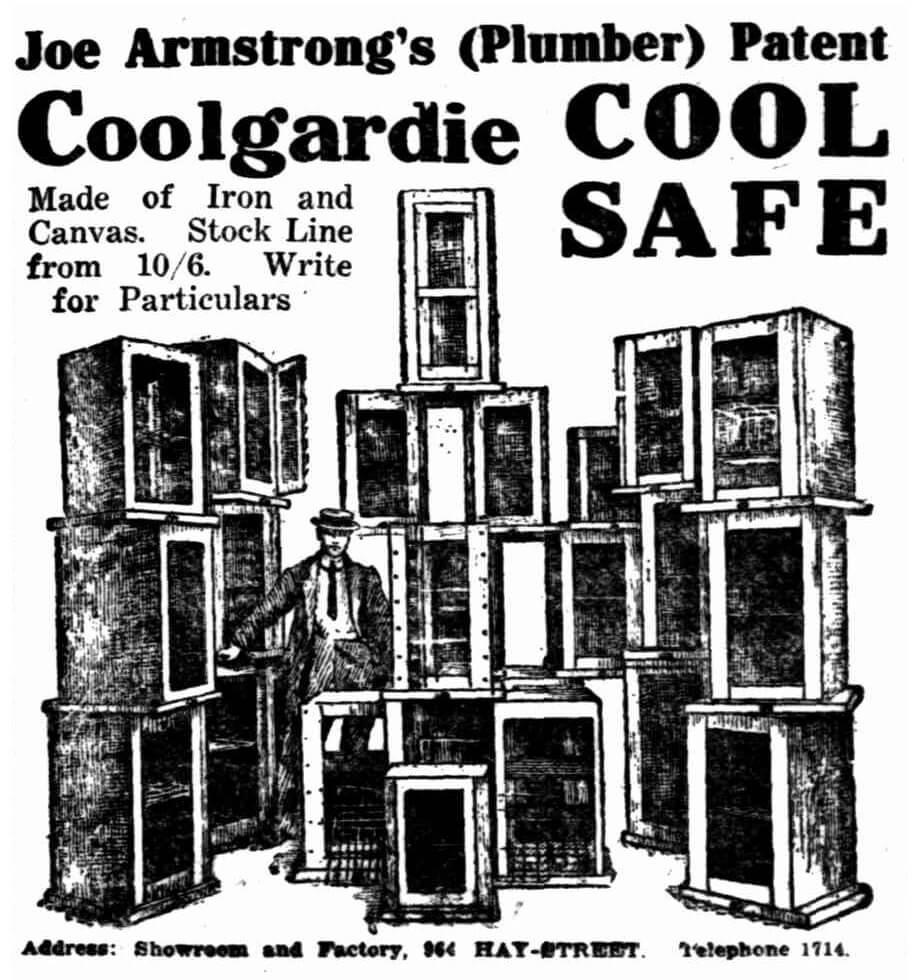

Simple Coolgardie Safes could be bought for as little as 10 shilling and sixpence. The ‘fancier’ models sold for about 39 shillings (£3/3-, or three guineas).

Most Coolgardie Safes were home-made. According to one reporter in Table Talk, ‘the handy woman (or her husband) would find no difficulty in making one at home’, at the cost of about 4 shillings. Plans were published in newspapers and magazines. The Australian Home Beautiful provided this sketch in 1931. The instructions, it was claimed, could be easily followed by amateur carpenters:

It is estimated that by the 1930s three out of every four households in Australia had a Coolgardie safe. It remained a common household item until the mid-twentieth century, particularly in rural areas.

The Ice Chest, or ‘Icebox’

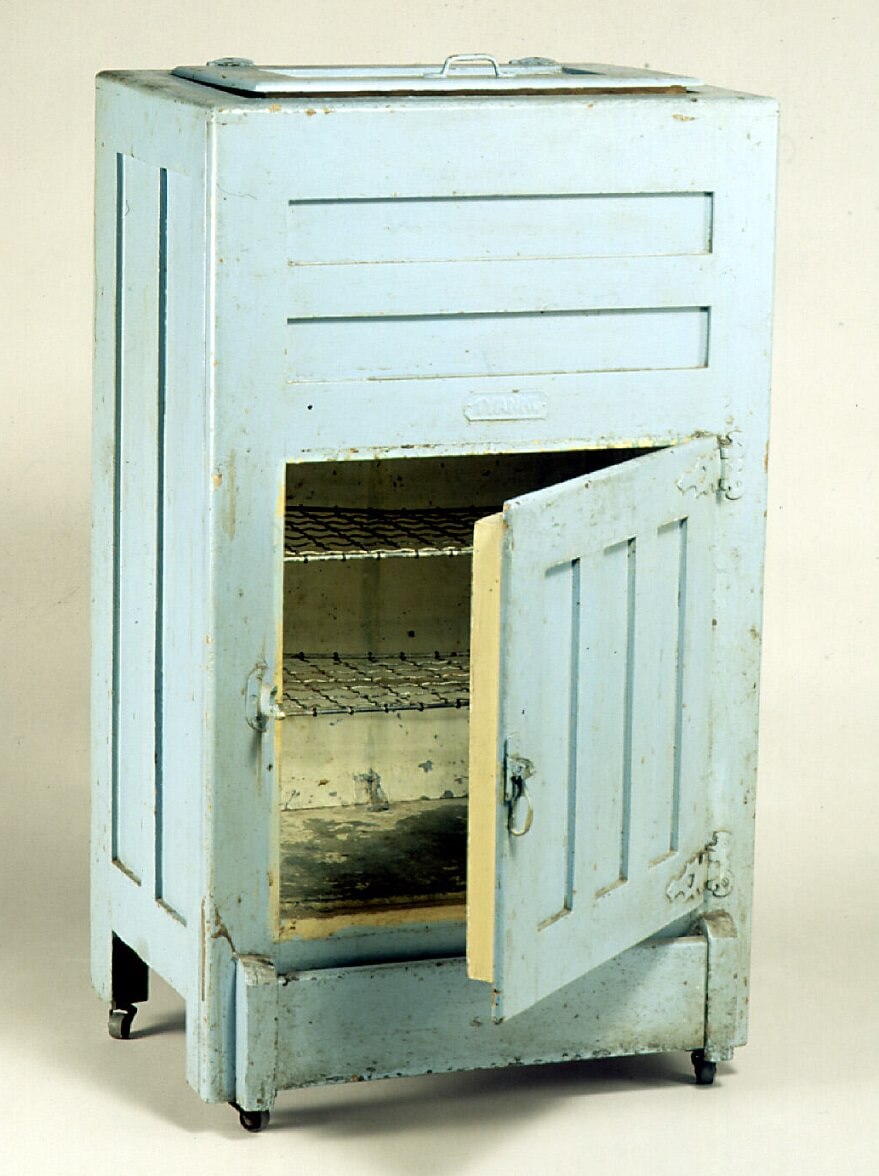

Australian ice-chest, c. 1939, with a cabinet of Australian oak, insulated with charcoal.

Reproduced courtesy Powerhouse Museum

The ever-present problem of the housewife, especially during warm weather, is food preservation. Daily foods, such as milk and meat, spoil very rapidly, and need constant protection to ensure their purity.

The Daily Telegraph, 25 October 1933

An ice chest ― also known as an ‘icebox’ ― comprised a free-standing cabinet made of wood and lined with galvanised-iron or the more expensive porcelain enamel. The cabinets were commonly insulated with charcoal or cork, but a range of materials was used ― fur pelt, hair, wool, felt, ash, even asbestos. A large block of ice was placed in a tray at the top of the cabinet. The melted water was piped from the ice tray to a drip tray underneath the chest. Several shelves inside the chest stored the food.

Ice chests were used in restaurants and hotels in Victoria from the mid-nineteenth century. Domestic ice chests were sold from the late-nineteenth century and used until the 1950s.

The ice chest was touted a ‘necessity’ for the time-poor (and thrifty) housewife:

For a small-size chest costing £3 four blocks of ice at 5d each is a week’s supply in normal summer weather, with perhaps an extra one sometimes in February – 1/8 to 2/ per week at most for about five months. Now, think of all the odd half-pints of milk which would go sour, the meat which has to be got at the last possible minute, and all cooked at once; the butter (or oil) running about in its dish before the meal begins; no jelly, lemon snow, blanc mange, etc. (for certain), nothing, in fact, raw or cooked, off the housekeeper’s mind for more than an hour or two.

From experience and careful watching I firmly believe that milk, meat, puddings saved by being kept in an ice chest really represent well over 1/ per week, and the balance is money well spent, for, it means that light, nourishing, and, above all, appetising food can be provided on the hottest day… [the housewife] is saved endless worry as to whether such a thing will be eatable when next wanted, and much time spent in searching for a cool spot and moving things to suit the sun – also putting butter in patent coolers and keeping them moist.

The Sydney Morning Herald, 3 January 1917

But they were not within the means of all households, with prices ranging from £3 to £5 for a shop-bought model. In the 1920s only one fifth of city houses in Australia owned an ice chest: and on farms and small towns the ice chest was unheard of.

As useful as they were, ice chests were far from foolproof. They kept the food cool, but not chilled, and required a large block of ice to be delivered twice weekly, or daily in the summer months. Food spoilage was common, and the boxes became rank and mouldy.

Countless handy hints and tips were published in newspapers and women’s magazines:

As the warm weather approaches it is more than ever important to give special attention to the ice chest. No matter how dainty-looking your ice chest is – with its seamless snow white porcelain lining and glass shelves – it needs cleaning just as much as an old-fashioned zinc-lined refrigerator needs it.

Once a week everything should be taken out of the food compartment and the walls and shelves washed with tepid water in which a few drops of ammonia have been dropped. In the rinsing water put a pinch of baking soda. It will be easy, with a small funnel, to pour boiling water and soda down the drain-pipe, and at any hardware store you can buy one of those long-handled wire brushes to push up and down the pipe and make it thoroughly clean of the slime that collects in it.

Sunday Times, 3 September 1922

Fill a small net bag with pieces of charcoal; keep this in your ice chest. You will find this keeps the air sweet and free from all smells.

Cairns Post, 1 June 1940

The following article, published in The Age in 1924, has a particularly urgent tone: it ‘behoves the housewife to pay attention to her ice chest’:

Shop keepers could be fined for storing food in filthy ice chests. George Marcellos was fined £3 in 1926, with 8s costs, for ‘having an unclean ice-chest’. An officer of the Board of Health stated that

… he found an ice-chest stored with butter, lettuce and cucumber. The interior of the chest was littered with cobwebs, while a quantity of decomposed vegetable matter gave off an offensive smell.

In the same year, store owner, John Colquhoun of Burwood, was fined £5, in default of 21 days’ imprisonment, for not keeping his ice chest ‘free from foul odours’.

Ice Chest

When summer comes, so hot and dusty,

Butter melts, and food gets musty,

There’s one reason,

At this season,

The ice chest is our friend so trusty.

Modern times bring their inventions,

To buy a fridge is our intention,

But funds are low,

As our purses show,

And the price brings forth contention.

So if by now, you have not guessed,

The answer to your quest,

The cost too high,

The frig. to buy.

We just fall back on the old ice chest.

Poem by Mrs. N. Hammersmith, published in Port Adelaide District Pictorial, 19 June 1952

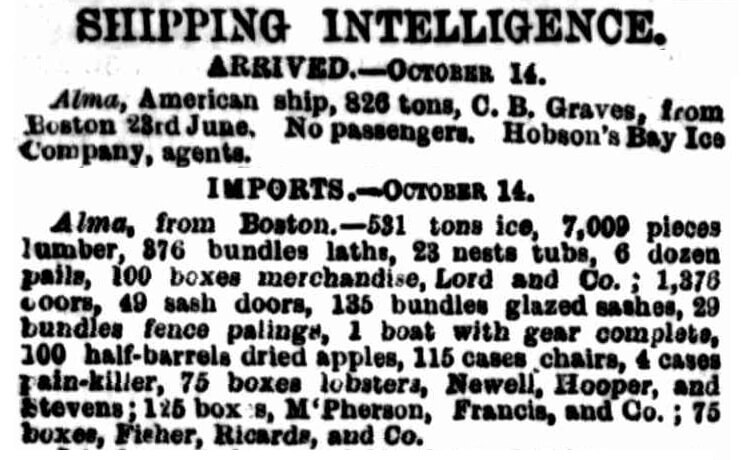

The Ice Trade

Of course, having an icebox relied on regular deliveries of ice.

Ice became available in Melbourne from the mid-nineteenth century, when it was cut from winter ponds near Boston in the United States of America and shipped to Australia.

The thick ice covering the ponds was cut neatly with the aid of an ice plough, and in the more severe winters two harvests of ice could be taken off. The heavy horses that pulled the ice plough also hauled the ice to the storage house on the shores of the lake. There the ice was conserved until warmer weather spurred local demand or an order arrived from a distant city. The blocks of ice – many of them weighing more than 45 kilograms – were carried by railway to Boston and other ports where deep-sea sailing ships were at anchor. In the hold of a wooden ship the blocks were stacked side by side, and one on top of the other, so that in the end the ship’s holds was one huge block of ice.

Geoffrey Blainey, Black Kettle & Full Moon, Daily Life in a Vanished Australia, Melbourne, Penguin Books Ltd, 2003

More than one third of the ice melted on its journey. Even more was lost after it arrived, particularly if it travelled up-country to the gold fields in Ballarat and Bendigo. Blainey writes:

A block of ice that reached a goldfield 150 kilometres from Melbourne was by then perhaps only half of its original size. In the eyes of rich and thirsty gold-diggers, that made it all the more precious.

Ice was a desirable commodity in Gold Rush Melbourne. At the popular (and expensive) Criterion Hotel, punters paid two shillings for a pound of ice in 1853, an exorbitant price even for the lucky gold digger. Ships carrying thousands of tons of ice arrived in Melbourne’s ports throughout the 1850s and 1860s.

Artificial ice was first made in Australia in 1851 by James Harrison, a Scottish-born newspaperman. At Rocky Point in Geelong, Harrison designed and built the world’s first refrigeration system, using sulphuric ether as the refrigerant. In November 1858 he founded the Victoria Ice Works in Melbourne and began to produce ice in commercial quantities.

Fun Fact! In his early years Harrison was unable to compete with the imported ‘Boston Ice’. Buyers claimed that his artificial ice wasn’t as cold!

Read about ‘Mr Harrison’s Ice Making Machine’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 8 March 1859.

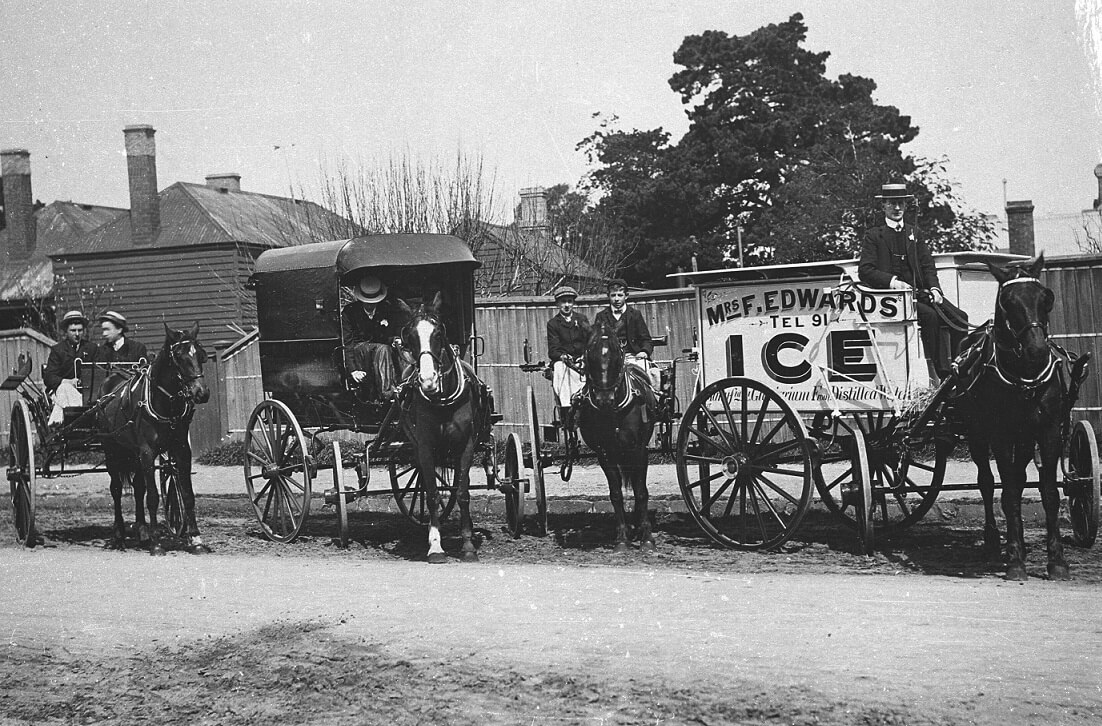

By the early-twentieth century several ice works operated in Melbourne and the ‘iceman’ became a fixture on city roads during summer months, delivering ice to households once or twice per week. The deliveries were made by horse and cart, with icemen using hessian bags to pad out their shoulders and lug the huge lumps of ice into homes.

Mrs Edwards was a successful businesswoman, operating a store in Church Street, Brighton, after her husband died. The store delivered all manner of fresh food ― milk, butter, eggs and ‘fresh rabbits daily’. Ice was ‘always on hand’.

The Refrigerator

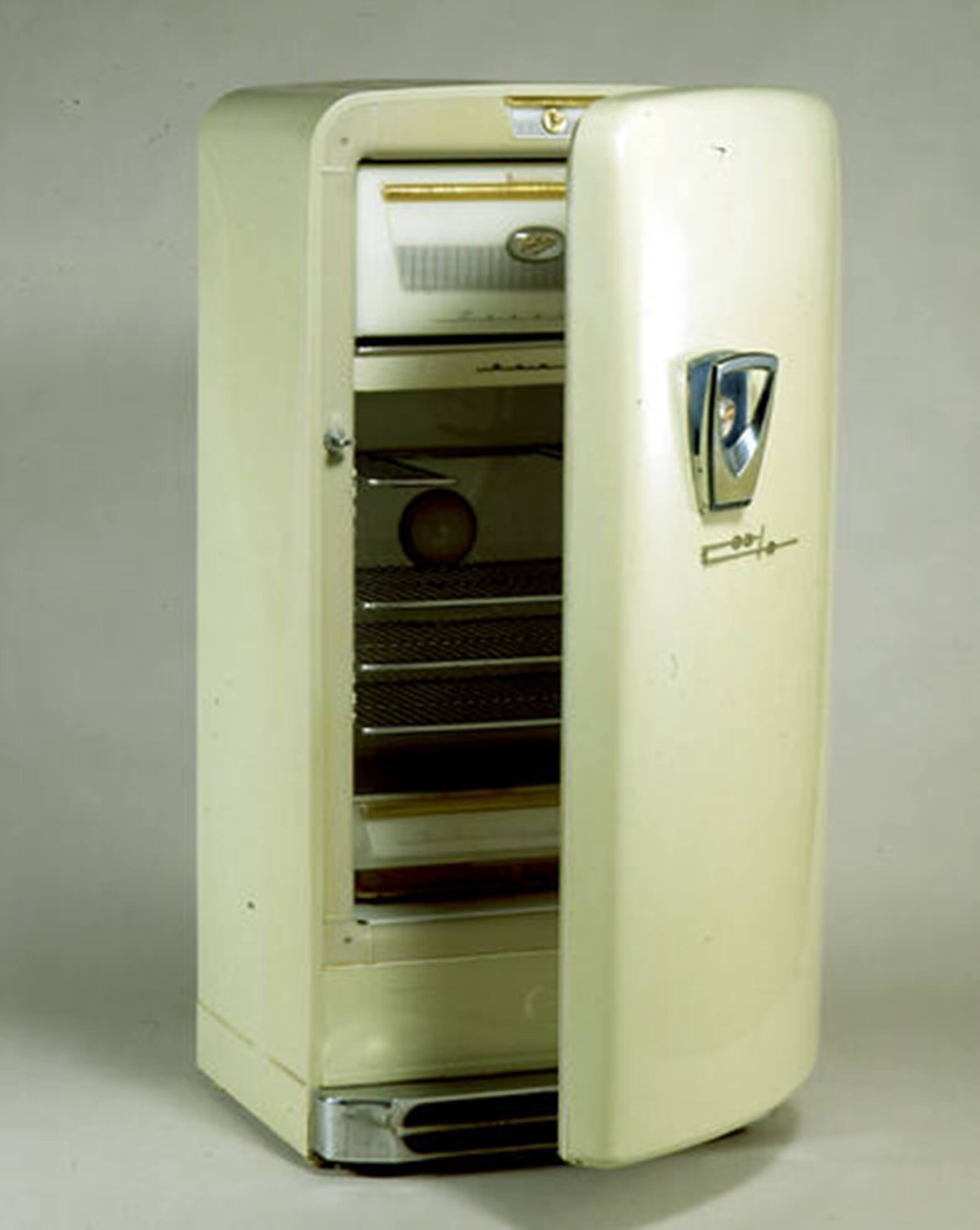

Colda Refrigerator, 1958

Reproduced courtesy Museums Victoria

This Colda refrigerator was purchased by a young couple in Chadstone, Victoria, in 1958. It is on display in our exhibition, Belongings: Objects and the Family, on loan from Museums Victoria. The couple borrowed money from their family to buy the fridge and paid them back at 10 shillings per week. The fridge was eventually replaced with one that had more freezer space, but it was never thrown out, rather stored with other obsolete whitegoods in the garage.

In the 1950s Colda refrigerators sold for about £170 — a significant outlay for most families. The average yearly wage for a (male) factory worker was only £296.

Refrigerators first appeared in (a few) Australian homes in the early-twentieth century. Imported models included the Kelvinator from 1918, and the ‘Monitor Top’, made by General Electric between 1927 and 1936. (The fridge was nicknamed the ‘Monitor Top’ because the exposed round condenser unit on top of the cabinet resembled the cylindrical gun turret of the Civil War gunship, the USS Monitor.)

The ‘Monitor Top’, made of steel and lined with white porcelain, was much smaller than modern fridges, with only three shelves and a tiny freezer compartment. The exterior compressor was the first domestic compressor to be hermetically sealed (airtight). Advertising claimed ‘the ‘entire mechanism . . . [is] fortified against air, dirt and moisture with impregnable walls of steel’. The Monitor Top was a best-seller in America. In Australia it retailed for £69 in 1935, a considerable sum given the average weekly wage was just over £5 for adult males.

In the early-twentieth century refrigerators were a luxury: well beyond the reach of ordinary working families, who considered them a novelty and extravagance. And they were temperamental. Machines would short cycle (suddenly stop for short periods of time), fail to cool, and sometimes even interfere with the radio. To make matters worse, early refrigerators used ammonia, methyl chloride or sulphur dioxide as refrigerants. A series of poisonings and deaths from leaking refrigerant led to the development of the gas Chlorofluorocarbon (CFC’s) in the late 1920s. (In the 1980s CFC’s were found to have a devastating impact on the ‘Ozone Layer’, which blocks damaging solar ultraviolet radiation. Alternative ‘ozone-friendly’ refrigerants have since been developed.)

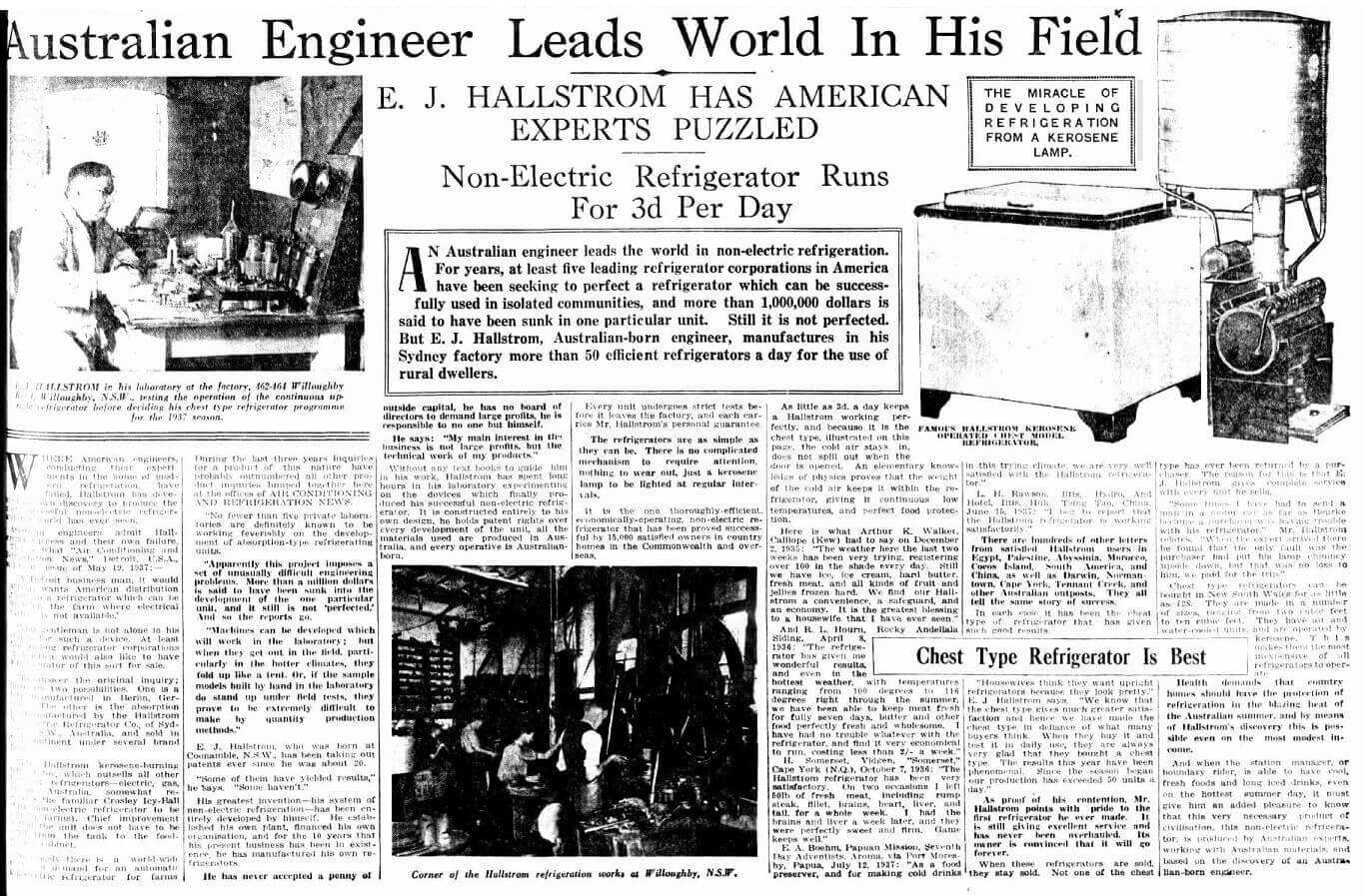

‘Australian Engineer Leads World In His Field’, Smith’s Weekly, 23 October 1937

Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia

The first Australian-made refrigerator ― the ‘Icy Ball’ ― was built by Sir Edward Hallstrom in 1928. The Icy Ball was a chest model run by kerosene and mostly sold to country properties which had no electricity or nearby ice works, relying on the primitive 'Coolgardie safe' to keep food cool. Hallstrom’s next refrigerator, the Silent Knight, was introduced in 1935 and ran on gas or electricity. The ‘Silent Night ’was quieter than other models on the market (hence the name), efficient and reasonably priced. Operating costs were its only downside:

Hailed as an ‘All-Australian Triumph’, the Silent Knight was sold as the ‘people’s refrigerator at the people’s price’. By the mid-1940s Hallstrom’s Pty Ltd was selling 1,200 refrigerators per week and employed over 700 people in their factory. In 1949 the Gilgandra Weekly informed their readers that demand was so high that there would be a delay of seven months for new stock.

The ‘Silent Knight’ electric refrigerator, made by Hallstrom’s Pty Ltd.

Reproduced courtesy Powerhouse Museum

In the late 1930s other Australian manufacturers entered the market ― Charles Hope, Colda, and Kirby ― and American manufacturers General Motors, Kelvinator and Westinghouse established manufacturing plants in Australia. Mass production and increased competition after the Second World War reduced costs, but refrigerators were not common in Australia until the 1950s.

Still considered a luxury in country areas until the 1950s, having a new fridge was a newsworthy event. The Mudgee Guardian announced the ‘new refrigerator owners in the district’ in January 1941, all proud owners of the Hallstrom Silent Knight.

Mudgee Guardian and North-Western Representative, 16 January 1941

Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia

‘This Christmas give mother the one refrigerator she’s always wanted… ‘, Australian Women’s Weekly, 12 December 1956

Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia

A virtual necessity

The great Australian dream of home ownership saw our cities spread during the second half of the twentieth century. Urban fringes expanded with affordable land releases and large residential blocks. New (and much larger) suburban dwellings were designed to accommodate all manner of modern domestic amenities and the refrigerator was at the top of the wish list. In 1955 it was estimated that 67 per cent of Melbourne homes had a refrigerator; by 1964 this figure had increased to 94 per cent. (The desire for refrigeration was not replicated in places where space was a constraint and the climate less demanding. British kitchen size, for example, had an impact on sales. Only 5.3 per cent of households in the United Kingdom had a refrigerator in 1953.)

Promoted as the ‘housewife’s’ friend’ or ‘tireless servant’, the refrigerator was redefined as an economical and labour-saving solution, essential to a well-planned modern kitchen. Advertisements emphasised their ‘time-saving’ potential. Shopping was no longer a daily chore: women could ‘buy when convenient’ and in bulk.

You will find your Prestcold is of infinite value. After a little time, you will wonder how you managed without it. Day in, day out, summer or winter, it keeps food fresh . . . wastage of food is eliminated. You can buy in larger and more economical quantities without fear of the food deteriorating.

Pressed Steel Company Limited, Prestcold Catering (Ocford 1959), p.1, in Helen Peavitt, Refrigerator: The Story of Cool in the Kitchen, London, Reaktion Books, 2017

Although life with her children was busy, with a lot of time spent shopping, washing and cleaning, [Mrs Morrison] was spared some of what would have previously been daily tasks: ‘On some mornings . . . I would go down to the butchers or fish shop . . . And then in the afternoon I would take them [the children] out to the park.’

Reminiscence of Mrs Morrison, from Lancashire, in Elizabeth Roberts, Women and Families: An Oral History, 1940–1970 (Oxford, 1995), p. 30, in Helen Peavitt, Refrigerator: The Story of Cool in the Kitchen, London, Reaktion Books, 2017

The Australian Women’s Weekly, 14 November 1951

Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia

Advertisements like this suggested that the housewife’s work would be replaced by new labour-saving appliances: ‘Happy the husband who enjoys the restful atmosphere of an easily run home. Happy is the wife who can run such a home – whose day is not a weary round of chores, who can find time to relax, see her friends and think of herself’.

The Australian Women’s Weekly, 1 May 1943

Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia

An expanding range of electric appliances promised the housewife some escape from domestic drudgery.

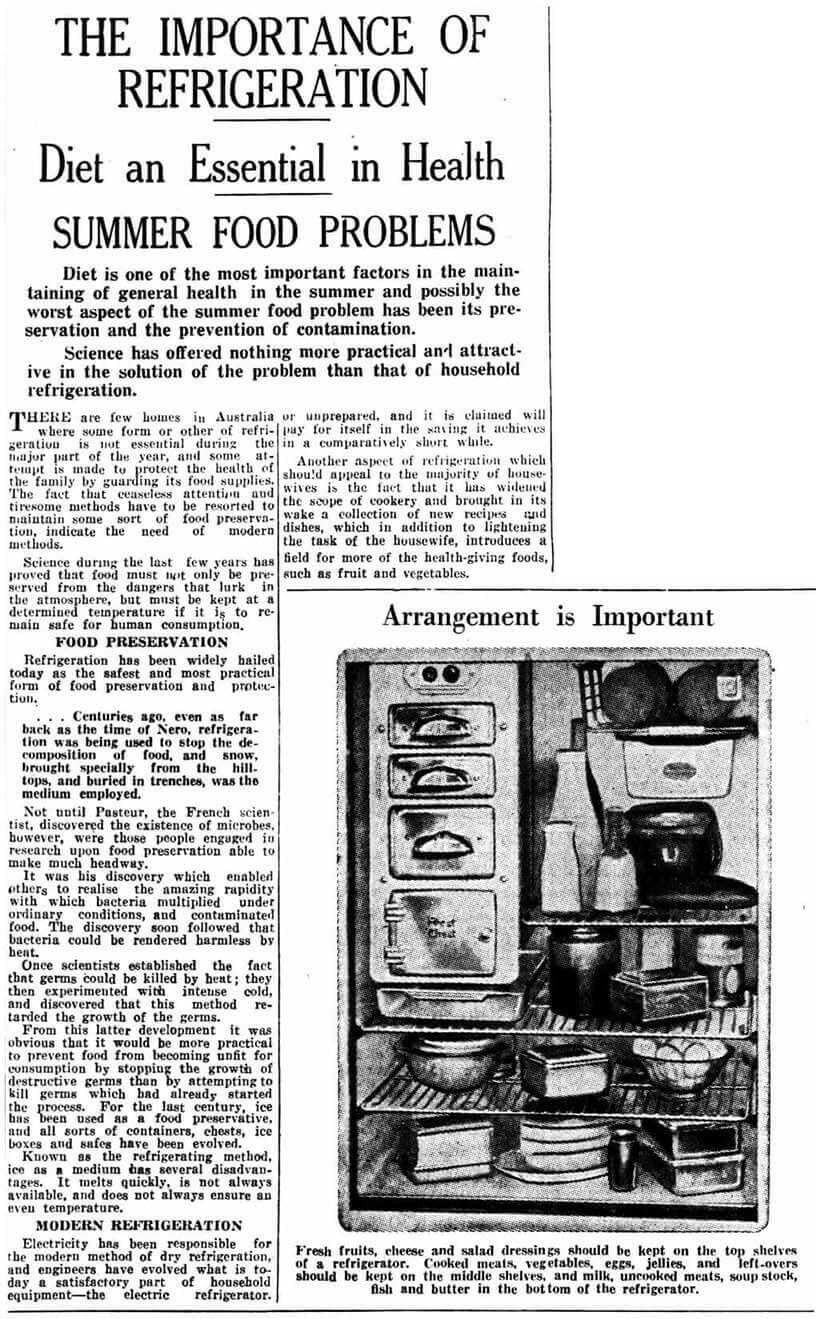

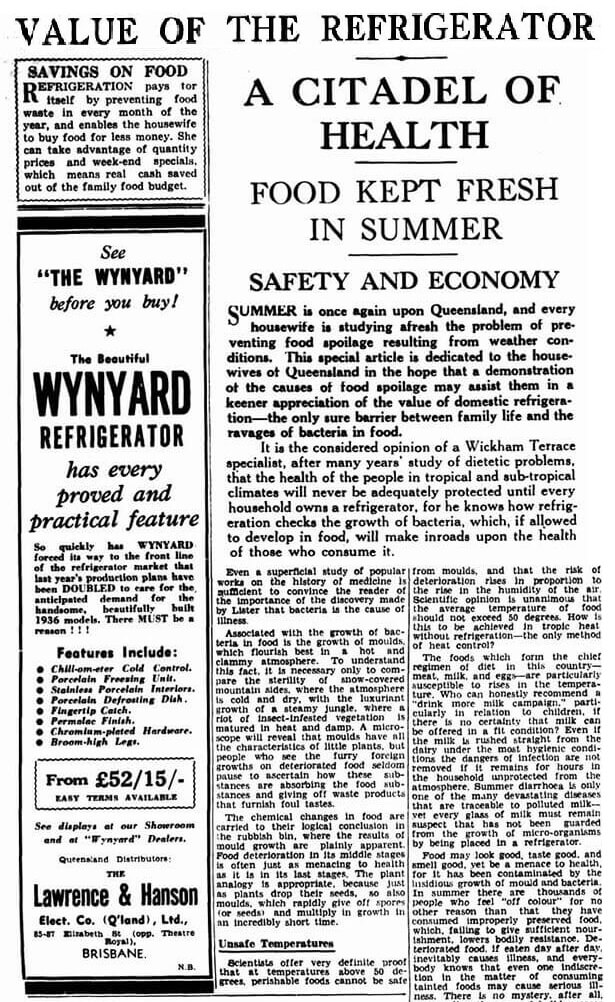

The refrigerator’s chief function ― preserving food ― became quickly linked to the responsibilities of the housewife to provide a clean, safe environment for her family. Articles appeared in newspapers supporting the value of refrigeration and its ‘health-giving’ benefits. Weekly magazines provided advice on appropriate food handling and hygiene routines.

Sometimes the warnings were gently given, with ‘cosy’ adverts portraying mothers dishing out treats from the refrigerator. But often advertisers played the guilt card more strongly with dire warnings about the potential health risks and dangers posed, especially to children, by contaminated or improperly kept food.

Helen Peavitt, Refrigerator: The Story of Cool in the Kitchen, London, Reaktion Books, 2017

The Courier Mail went so far as to call the refrigerator ‘A Citadel of Health’!

12 October 1936. Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia

Advertisement for the ‘World Famous Westinghouse’, Australian Women’s Weekly, 14 October 1953

Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia

Advertising targeted the busy housewife who valued thrift and convenience, and cared about the health of her family. This Westinghouse fridge boasts ‘every feature a woman wants and needs.’

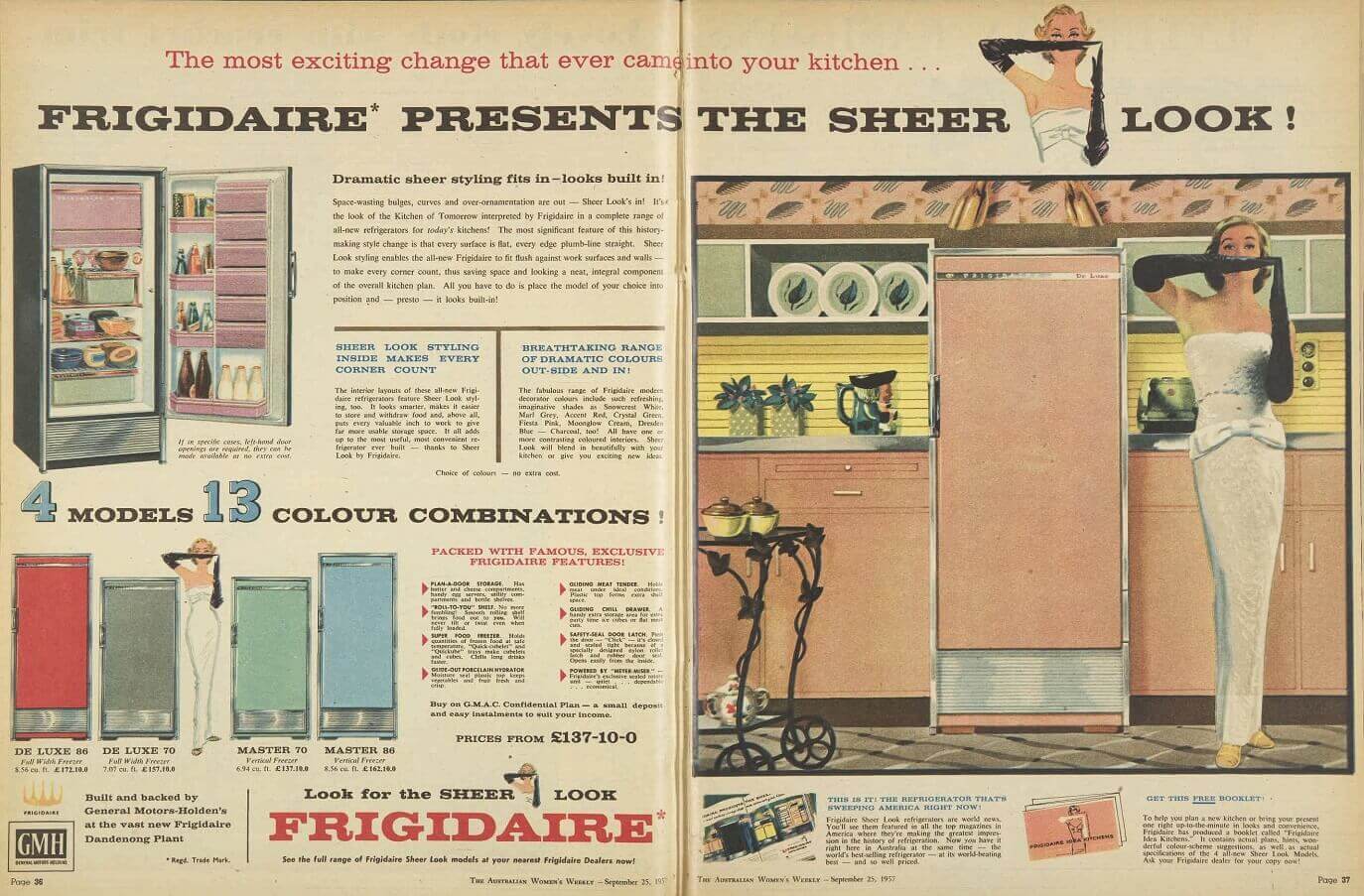

From the late 1950s design was increasingly used to market refrigerators. Refrigerators were sold in a range of fashionable colours and even colour-coordinated with other appliances in the kitchens.

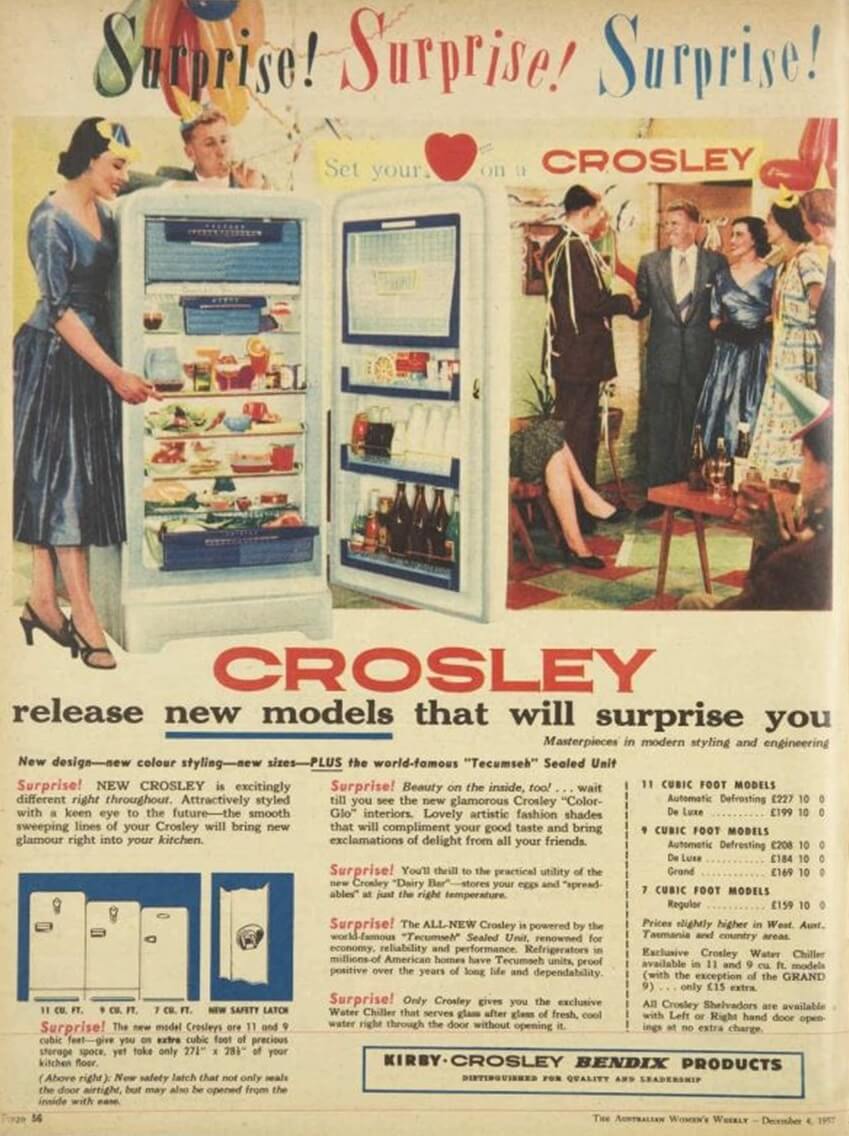

Advertisements raised the refrigerator beyond the functional: it became a symbol of family life reflecting style and taste. The ‘Sheer Look’ by Frigidaire in 1957, for example, offered customers thirteen (rather charming sounding) colours to choose from, amongst them ‘Fiesta Pink’ and ‘Moonglow Cream’. The ‘new season Pope’, released in the same year, came in a wide range of interior and exterior colour schemes: ‘just waiting to tone in with your kitchen colours’. Corsley refrigerators promised ‘beauty on the inside, too’, with new ‘Colour-Glo Interiors’:

Lovely artistic fashion shades that will complement your good taste and bring exclamations of delight from all your friends.

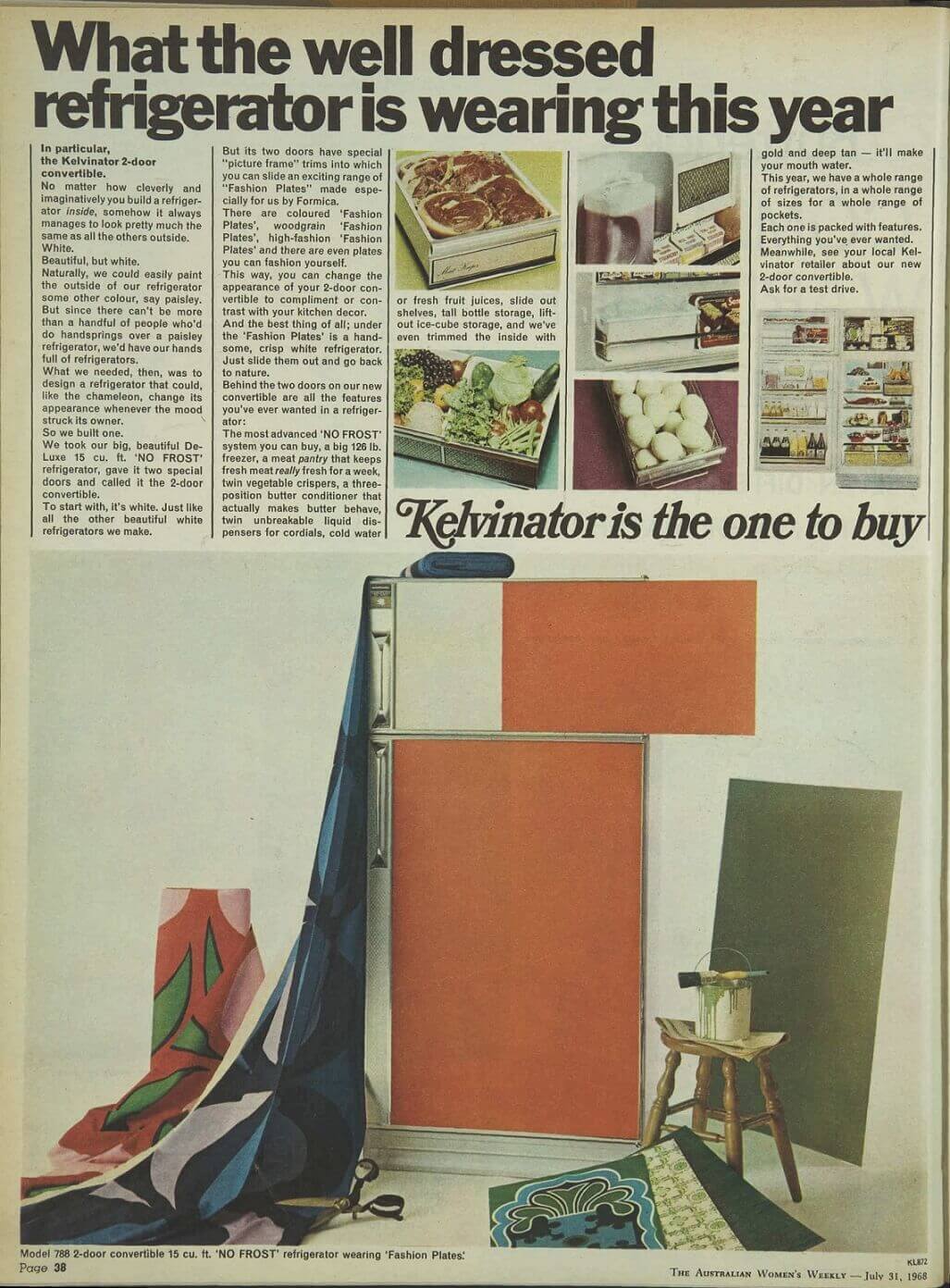

Kelvinator launched their ‘Convertible’ in the late-1960s. Its two doors had special ‘picture frame’ trims into which you could slide an exciting range of ‘Fashion Plates’ made especially by Formica.

There are coloured ‘Fashion Plates’, woodgrain ‘Fashion Plates’, high-fashion ‘Fashion Plates’ and there are even plates you can fashion yourself.

This way you can change the appearance of your 2-door convertible to complement or contrast with your kitchen décor.

Targeting the fashion-forward housewife, advertisements came with the tagline ‘What the well dressed refrigerator is wearing this year’.

Advertisement for Frigidaire’s ‘Sheer Look’ refrigerator, with its ‘breathtaking range of dramatic colours’, Australian Women’s Weekly, 25 September 1957

Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia

Advertisement for ‘the glamorous New Season’s ‘Pope’ Fridges’, 20 November 1957

Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia

Advertisement for the new model Crossley refrigerator – ‘Attractively styled with a keen eye to the future…’, 4 December 1957

Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia

Advertisement for the Kelvinator refrigerator, complete with ‘Fashion Plates’, 31 July 1968

Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia

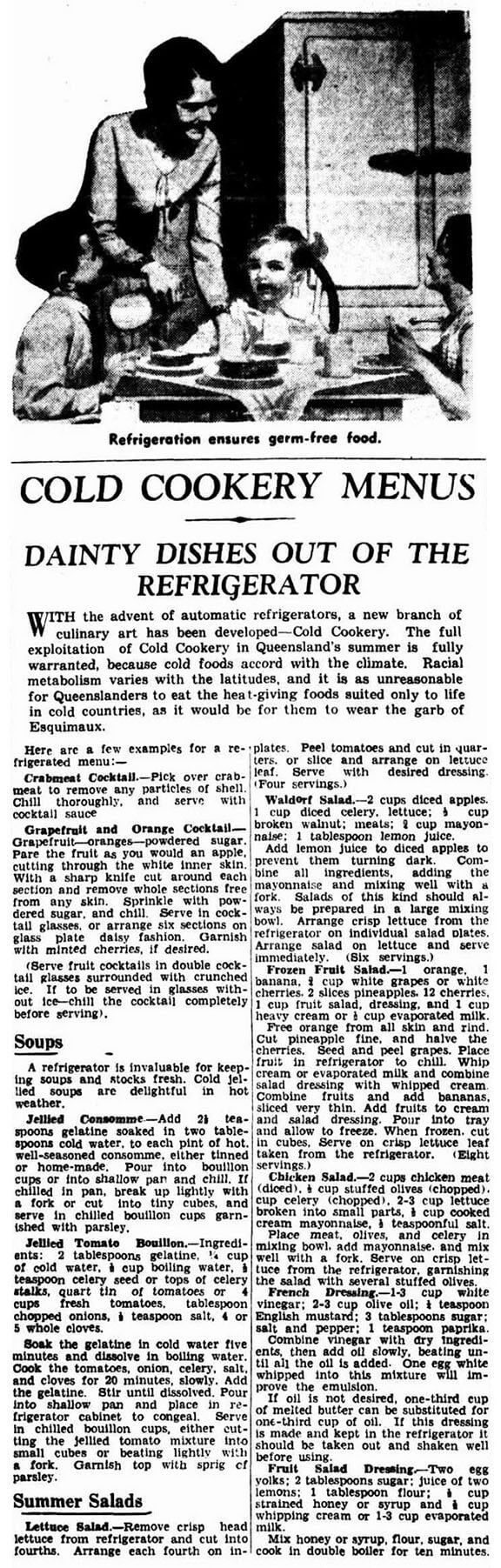

Cold Cookery

Refrigerators undoubtedly reduced the sheer physical drudgery of shopping. They also enabled greater food choice. By the mid-twentieth century it was possible to buy off-season fruit and vegetables, shipped in cold-storage and ready to eat. Refrigerated ‘foodstuffs’, such as individual yoghurt tubs, were invented, and frozen foods followed ― ice cream, fish fingers and ‘TV Dinners’, popular with working mothers trying to juggle home and work responsibilities.

As millions of white women entered the workforce in the early 1950s, Mom [sic] was no longer always at home to cook elaborate meals—but now the question of what to eat for dinner had a prepared answer. Some men wrote angry letters… complaining about the loss of home-cooked meals. For many families, though, TV dinners were just the ticket. Pop them in the oven, and 25 minutes later, you could have a full supper while enjoying the new national pastime: television.

Frozen foods are increasingly popular today. An inventory of my own freezer drawers reveals an array of time-saving meals ― frozen pizza, potato chips and wedges, and the don’t-come-home-from-the-supermarket-without them ‘Dino-Nuggets’ (chicken nuggets in the shape of a Brontosaurus).

Home cooking changed too. Iced desserts replaced older favourites like junket and blancmange. Novel dinnertime dishes included extravagant salads, jellied meats and chilled puddings. Recipes were published in newspapers and women’s magazines. Australian manufacturer, Charles Hope Ltd, produced a cookbook, with parfaits, eggnogs and fruit cups.

‘Cold Cookery’ demonstrations were given in country towns:

Travelling in the display van is Miss J. A. S. Wyles B.Sc., who is giving “cold cooker” demonstrations in country towns. With the aid of the Electrolux refrigerator, Miss Wyles is demonstrating how complete three and four course meals can be produced with a refrigerator.

The lectures, which will be given in halls or picture theatres, are designed to show that a refrigerator is not a glorified meat safe, but is a means of producing a host of appetising summer dishes.

‘Leftovers’ ceased to be a problem: instead, they could save time and money. Cookbooks provided tips and tricks for adapting last night’s dinner into something tasty. The issue of ‘how’ to store the leftovers saw the plastic container brand Tupperware invented in America in 1946. The first Tupperware party in Australia was held by Mary Paton in her mother’s home in Camberwell, Melbourne, in 1961.

Advertisement for the Tupperware ‘Party’ – ‘You’ll agree shopping has never been so fun’, Australian Women’s Weekly, 18 March 1964

Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia

Advertisement for Tupperware’s exclusive ‘airtight’ seal locks – ‘keeps moist foods moist, crisp foods crisp’, Australian Women’s Weekly, 27 October 1965

Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia

Over time refrigerators came to be regarded as a necessity. Almost every household in Australia has (at least) one ― 99.8 per cent in 2008 ― and models come in a range of sizes and finishes. There is a seemingly endless array of special features now available. Ice-makers and filtered water dispensers have become quite common. One fridge, the ‘HomePub’ dispenses chilled beer. The ‘Smart’ fridge is the latest high-end option. It can check your smart doorbell's video feed, order new groceries based on an automated inventory, or suggest recipes based on what you actually have in the fridge.

What would you like your refrigerator to do for you?

Further reading

Websites

Online resources

Australian Food Timeline: 1923 First Australian domestic refrigerator

Jstor Daily: The Complicated Politics of… Refrigerators

Museums Victoria: Domestic Refrigeration & Refrigerators, Refrigerator - Charles Hope, Refrigerator - General Electric

National Museum of American History: Keeping your (food) cool: From ice harvesting to electric refrigeration

Smithsonian Magazine: A Brief History of the TV Dinner

Secondary sources

Australian Academy of Technological Science and Engineering, Technology in Australia 1788-1988, Melbourne, Australian Academy of Technological Science and Engineering, 1988

Geoffrey Blainey, Black Kettle & Full Moon, Daily Life in a Vanished Australia, Melbourne, Penguin Books Ltd, 2003

Helen Peavitt, Refrigerator: The Story of Cool in the Kitchen, London, Reaktion Books, 2017

Helen Watkins, ‘Fridge Space: Journeys of the Domestic Refrigerator’, thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Graduate Studies, The University of British Columbia, June 2008

Judith O’Callaghan, ed., The Australian Dream: Design in the Fifties, Sydney, Powerhouse Publishing, 1993

Peter Cuffley, Australian Houses of the Forties & Fifties, Victoria, Five Mile Press, 1993

Peter Hertzmann, ‘The Refrigerator Revolution’, Dublin Gastronomy Symposium, 2016

Ruth Schwartz Cowan, More Work for Mother: the ironies of household technology from the open hearth to the microwave, New York, Basic Books, 1983

Shelley Nickles, ‘”Preserving Women”: Refrigerator Design as Social Process in the 1930s’, Technology and Culture, vol. 43, No. 4, 2002, pp. 693-727

Tony Dingle, ‘Electrifying the Kitchen in Interwar Victoria’, Journal of Australian Studies, no. 57, 1998, pp. 119-127