Until very recently, almost every woman owned a sewing basket, or sewing box. It stored her pins, needles and thread, but also other essential tools like scissors, thimbles, darning ‘mushrooms’, or embroidery equipment. Large boxes might also store pieces of fabric or patterns. While some men were also skilled at sewing, it was generally considered women’s work and most sewing baskets were owned by women.

Sewing baskets came in many forms, from the decorative to the strictly utilitarian. Many were simple caneware baskets, lined with fabric and often padded.

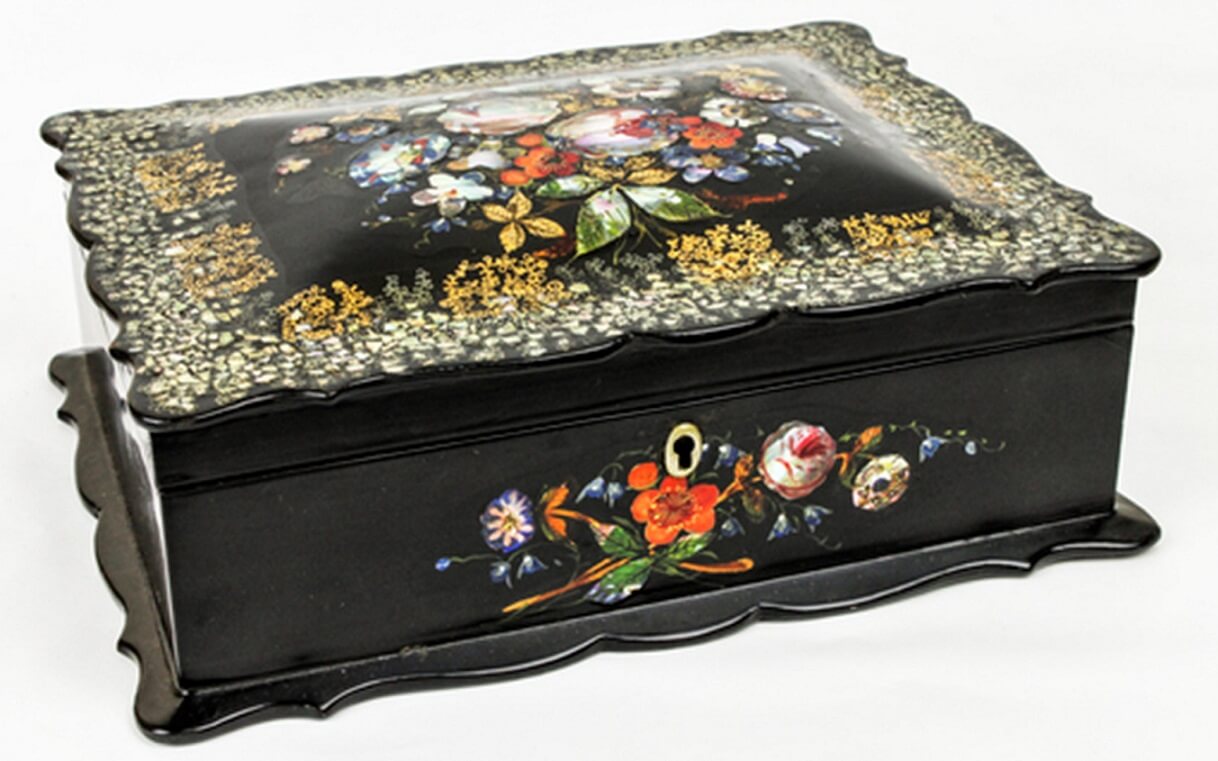

Others were more elaborate, like this papier maché sewing box with abalone shell inlay, owned by Jean Young (1811-89) and brought with her from Scotland in the 1850s. It was almost certainly owned by another woman in her family before her. This sewing box was included in the Belongings exhibition.

Jean Young married William Hill in Scotland and arrived in Victoria in the early 1850s. They had seven children. Clothing a family of this size was a constant challenge and many women sewed well into the night. Their letters often mention overflowing mending baskets. The work box is lined with lilac satin and contains needles, thread, thimbles, buttons, and a pin cushion.

Sewing boxes were also made of polished wood and might contain many small compartments to store different articles. The wooden box shown here was used by an early resident of Port Fairy throughout her life.

Work box polished wood with pearl inlay, and original internal compartments, c. 1850.

Used by Miss Mary Southcombe in Port Fairy from 1854.

Courtesy Port Fairy Historical Society and Archives

These days many sewing boxes are strictly utilitarian objects made of plastic and could serve many functions.

First Nations peoples in Victoria also sewed, using pierced bone and kangaroo sinew to join skins together to make cloaks and other clothing. Possum-skin cloaks were especially prized and were sold on the Goldfields to miners who were glad of their warmth in the bitter winters. Artist Eugene von Guérard was one who purchased a possum cloak and sketched the transaction for a later painting.

Eugene von Guérard, Aborigines Met on the Road to the Diggings, 1854

Oil on canvas

Reproduced courtesy Geelong Art Gallery

Here miners examine possum-skin cloaks to purchase, probably from a Dja Dja Wurrung family. Von Guérard himself owned a cloak. Possum-skin cloaks were made by First Nations People for generations and became valuable trade goods post-invasion. Later as more First Nations women and girls were confined to reserves, they were taught to sew with needles and thread.

Sewing in everyday life

For many decades the sewing basket was an essential item in a household, reflecting the huge range of sewing tasks that were part of everyday life. Until the 1860s almost all clothing was made by hand, whether in the home, or in a dressmaking establishment, and it involved hours and hours of sewing. We once counted the stitches in the flounced skirt of an 1850s dress and estimated that there were more than 5,500 individual stitches in the skirt alone. That included yards and yards of seams, (a dress at this time commonly required some 25 yards of material to make). Then there were the intricate gathering stitches that created the fullness of the wide skirt, and the many tiny hemming stitches that created the finished edges, not to mention all the fiddly sewing involved in making decorative piped seams on the flounces. The bodice of the dress involved extensive gathering and ruching, and more piping, so all in all, the dress would have taken someone hours and hours (probably many long days) of careful stitching to make. The dress in question is illustrated here. You can also read about it in more detail here.

Household linen was also made at home, with fabric sold in lengths for sheets or towels, ready to be hemmed. Luckily most sheeting or toweling was sold in appropriate widths with selvedge (self-finished) edges, to reduce the amount of tedious (and time-consuming) seaming or hemming that would otherwise have been required. But a good deal of time was still involved in hemming the other edges. Catherine Anne Currie, who lived on a busy farm in Gippsland in the 1870s, was constantly busy providing for her family. Finding the time to sit and sew or mend was a challenge. But occasionally she would manage to get together with neighbours in the evening, often to sew together. On one evening she noted in her diary that she had hemmed one dozen pillowcases — no mean feat!

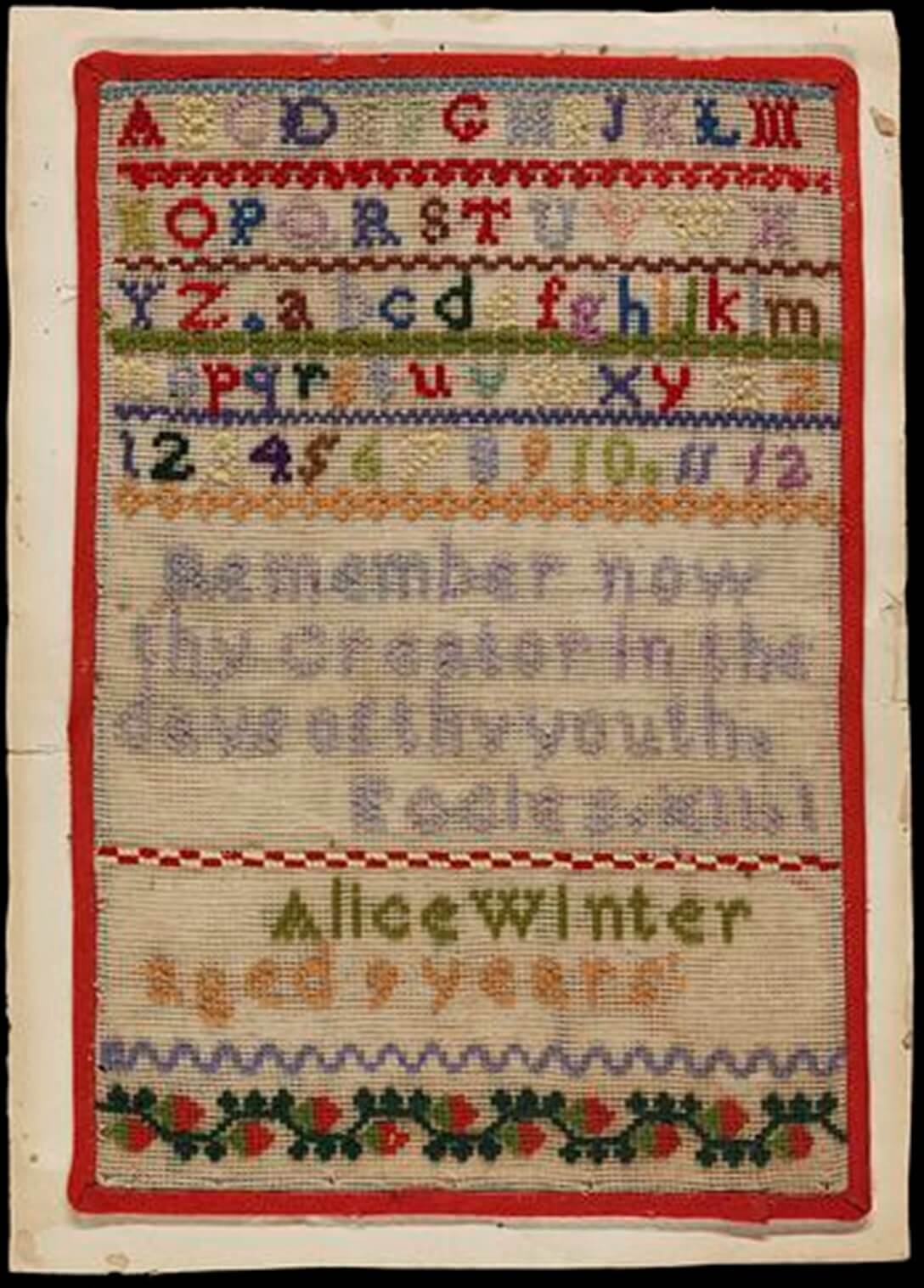

Sewing a neat seam and hemming with tiny stitches, were skills taught to girls from an early age. In fact, in the nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries little girls were usually taught to sew as soon as they were able to hold a needle. By the time they were eight or nine many could sew quite competently, as the many samplers in museum collections show clearly.

The sampler shows the alphabet in both upper and lower case, the numbers from 1-12 and a Biblical verse: ‘Remember now thy creator in the days of thy youth’ (from Ecclesiastes 12.1) along with the maker’s name and age. They are worked in coloured wool on a canvas ground. There are several samplers in the collection made by Alice Winter and her older sister Eliza, who died of fever in 1853 aged 11 years. One of Alice’s samplers, made when she was 10, included her address: ‘172 La Trobe Street Melbourne’. Samplers were a means of teaching young girls basic sewing and embroidery stitches and were sometimes kept by families framed for display.

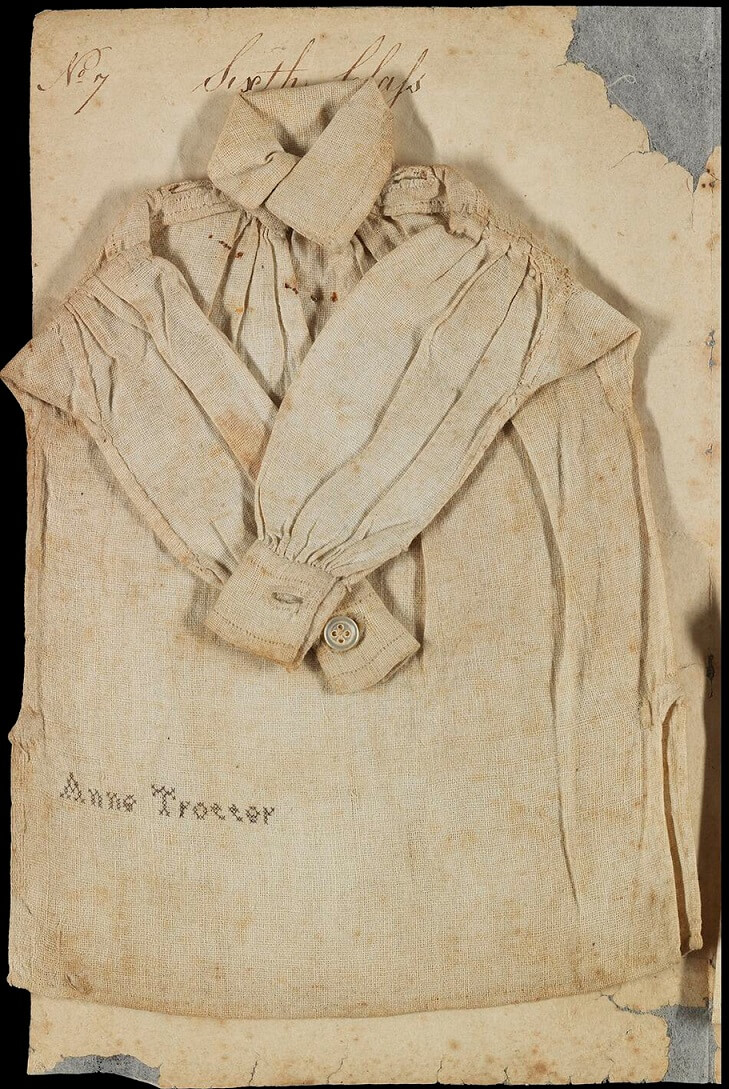

Some young women also made sample booklets, perhaps to show their competence in both sewing and embroidery stitches to a prospective employer. One extraordinary book is held in the collection of Museums Victoria and was made by Anne Trotter, who migrated to Port Phillip from Ireland in 1844 along with other members of her family. The book was made while she was a student at the Female Free School in Collon, County Louth in 1840, when she was aged 20. It was treasured by her family through the generations before being placed in the museum’s collection.

Page from a sample book made by Anne Trotter, in Ireland c. 1840, prior to her immigration to Port Phillip. Shows a miniature of a man’s shirt.

Museums Victoria

Needlework and class

Women of all classes sewed, although what they sewed depended on their social status and their resources. ‘Fancy work’, which could include embroidery, lace making and items of needlework craft, was popular amongst genteel women, who used it to occupy their time productively and to beautify their homes. They embroidered handkerchiefs, collars and cuffs, doilies, napkins and tray cloths, made handkerchief sachets and nightgown cases, and embroidered slippers or ‘smoking caps’ for their menfolk. Embroidered fire screens were popular throughout the nineteenth century and might be made in various sizes, from those used literally to shield the face, to more robust items of furniture. Often the women of a genteel household would work at their sewing together, either in the mornings or in the evenings gathered around candles placed on a ‘worktable’ in the drawing room. One such family evening was painted by Maria Brownrigg at Port Stephen in 1857.

Embroidered fire screen (and closeup), silk embroidery, 1900-1910

Courtesy Kew Historical Society

Worked by Winifred, Elsie and Louisa Hindson, descendants of the Hentys.

While much of this needlework found a use in the home, genteel women also busied themselves making articles for sale at fêtes and bazaars organized for charity. These were often described at some length in the colonial newspapers and give some indication of the range of articles offered for sale. They also named the various prominent women who organized the events and contributed their work. The tone and content of these articles is remarkably consistent over time, although as the overall size of the newspapers expanded, the detailed descriptions of these events followed suit. By 1900 the Australasian’s correspondent ‘Queen Bee’ could describe not only the goods on sale at various stalls, but also the outfits worn by the most prominent women in attendance. She also assured her readers that the stalls were all arranged ‘with the best possible taste’, should this be in any doubt!

Making over

But such women were often quite capable of turning their hand to more practical sewing if the need arose (or means were straightened). A clever makeover of a dress into a later style might allow a woman to keep up appearances, even if money was scarce. Lorinda Cramer cites many examples of middle-class women mending and making over their dresses to serve another season. She cites Isabella Ramsay noting in May 1858 that her sister’s family ‘were busy making winter dresses. I was busy mending mine.’ (p. 130) Clothing was also handed on within families, entirely without shame. If a young woman died, her clothing was sometimes sent to her sisters, even across the oceans to England, where it would be altered to fit.

For ordinary women altering clothing and mending were ever-present and essential tasks. In the nineteenth century repeated childbearing meant that women’s clothing required alteration on a regular basis. Wealthy women might hire a dressmaker by the day or longer, but other women performed these tasks themselves. Many dresses survive in museum collections showing alterations to bodice seams, additions to front fastenings, or altered waistlines to reflect both changing shape and changing fashions. Fabric, especially in the large quantities required to make gowns in the nineteenth century, was simply too valuable to waste. A skilled needleworker could refurbish clothing from one season to the next and alter clothing to accommodate pregnancy and nursing. At a time when maintaining a respectable appearance was paramount, a skilled needlewoman could make a substantial contribution to a family’s social standing.

Children’s clothing was routinely made at home, at least until the boys required suits and the girls were in their mid-teens. Baby clothing was made to accommodate the growing child, with waists made with tapes to draw them in or let them out, and long skirts that were worn until the child began to crawl. A competent needlewoman could easily extend the life of children’s clothing as they grew. Hems were let down, bodices made with tucks that could be unpicked, tears mended, collars ‘turned’, and stockings darned. Children in large families expected to wear hand-me-downs, from brothers or sisters and from cousins. Mending, of socks, stockings, frayed cuffs, or minor tears, was ever-present and many women despaired at their overflowing mending baskets. Such work was often done in the evenings, or in company with other family members. Women rarely sat down without their sewing.

Paid work

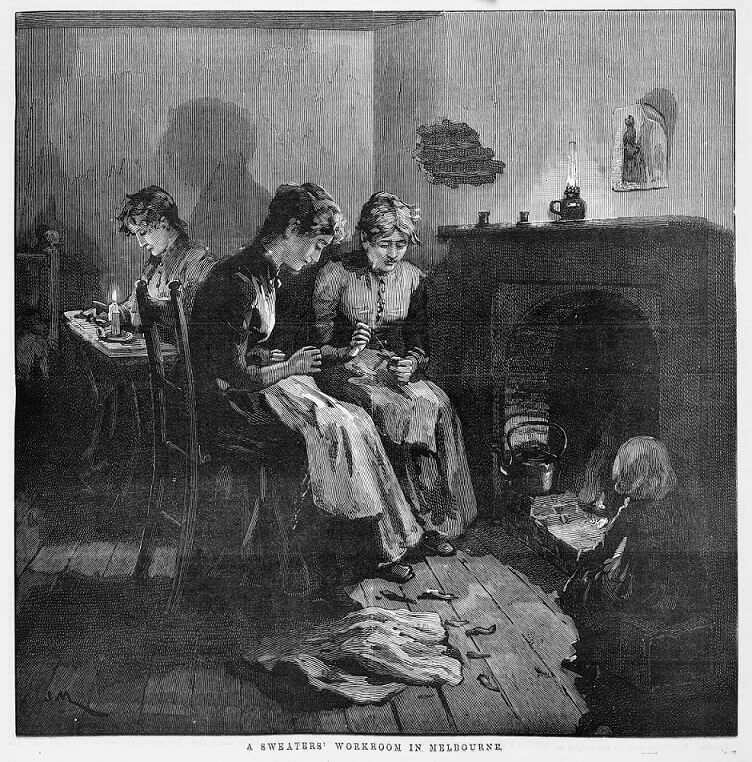

For poor women, sewing was a necessity but also sometimes an occupation. Seamstresses were required in all dressmaking establishments and often worked very long hours. Even after the advent of sewing machines to the larger factories, there were still many tasks that required hand-sewing, from the ‘finishing’ of men’s shirts to the sewing on of buttons. Sometimes this work was undertaken by outworkers, a practice known as ‘sweating’. These were women who for various reasons had to work from home. They collected unfinished pieces from the factory and returned the finished articles. Unfortunately, since almost all women could sew, seamstresses were very poorly paid and sweated workers were paid worst of all. There were repeated campaigns at the end of the nineteenth century to stamp out sweating, but little thought was given to finding such women replacement work. You can read more about sweating in Melbourne factories here.

Mending

In this time of cheap clothing the task of mending has almost disappeared, but for women in the past it was a constant chore. In the early-nineteenth century even small essentials like socks and stockings were often hand-knitted, and holes were routinely mended to make them last longer. Darning was an essential skill for life, and little girls were taught to darn neatly while very young. It was not only socks and stockings that required darning: often small tears in clothing were repaired in this way, or cuffs carefully darned to conceal fraying. Most sewing boxes contained a darning ‘mushroom’, a wooden tool designed to support the fabric while a hole was darned.

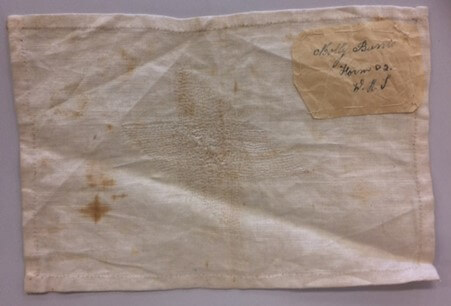

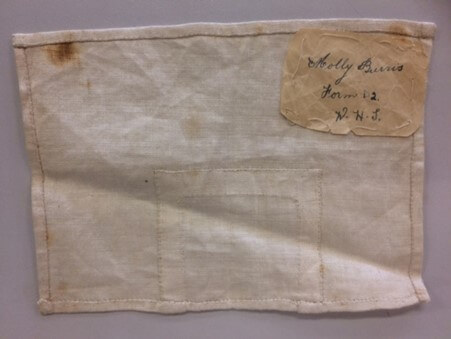

There are some examples of darning preserved in museum collections, although fewer than we might expect, given how much of women’s time the task consumed. However, these examples demonstrate the level of skill achieved in this mundane task. The aim of course, was to make the darn as inconspicuous as possible. Mending was evidently still taught in high schools in the 1940s, as this collection from Williamstown High School attests. The work was completed by Molly Burns, who was then in form 2D. Her work also included a neatly-executed patch.

Samples of darning (above) and patching (below) by Molly Burns, Williamstown High School, c. 1940s

Reproduced courtesy Williamstown High School Collection

The sewing machine

Given the amount of time involved in ‘plain’ sewing, it is not surprising that the invention of the domestic sewing machine was welcomed immediately. It was often the first labour-saving item to be purchased in a household, materially assisted by the clever adoption by the Singer company of a time-payment system. Singer quickly came to dominate the market. At first the needle was moved along by turning a handle, but this made it difficult to guide the fabric through the needle. The later invention of a foot treadle was a vast improvement, leaving both hands free and enabling seams to be sewn at speed. The first machines of the 1860s produced a chain stitch, but later models produced a straight seam with a lock stitch. The differing stitches are easily distinguished in garments. For many years garments were created using both machine and hand stitching, but by the twentieth century, most garments could be made entirely by machine, with the exception of decorative stitching or fine hemming.

Embroidering the home

The advent of the sewing machine did not mean the end of hand sewing — far from it! And by the early-twentieth century more women may well have found the time for the embroidery that once kept their genteel sisters occupied. Some women were extremely skilled at coloured embroidery and at the various forms of whitework embroidery (often known as broderie anglaise, or cutwork) that were popular in the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries. Some made elaborate and very beautiful tablecloths, that were truly heirlooms and could take many years to complete. Museums Victoria has a photograph of one woman at work on a cloth that had taken six years to that point.

The intricate border of this tablecloth featured drawn thread work and had taken six years to make. The patterns were created by pulling threads from the cloth and filling the spaces with different embroidery or lace-making stitches. The body of the cloth was also embroidered in whitework. Cloths like these could be kept for generations. A small tablecloth (or tray cloth) made by Minnie Rayner (née Roberts) between about 1900 and 1920 is still preserved by her descendants, although such linens rarely find a use today.

Women sometimes made these embroidered cloths as gifts for their children and grandchildren, specifically to serve as keepsakes, or as heirlooms. When Violet Marsden was diagnosed with cancer in the 1950s, she resolved to make each of her granddaughters a doily or a cloth to remember her by. The doily shown here was one of those she made. It is made of linen, embroidered with coloured silks and edged with crochet. Sadly, although Violet managed to work the embroidery on this doily, she was too ill to make the edging and asked a neighbour to do it for her.

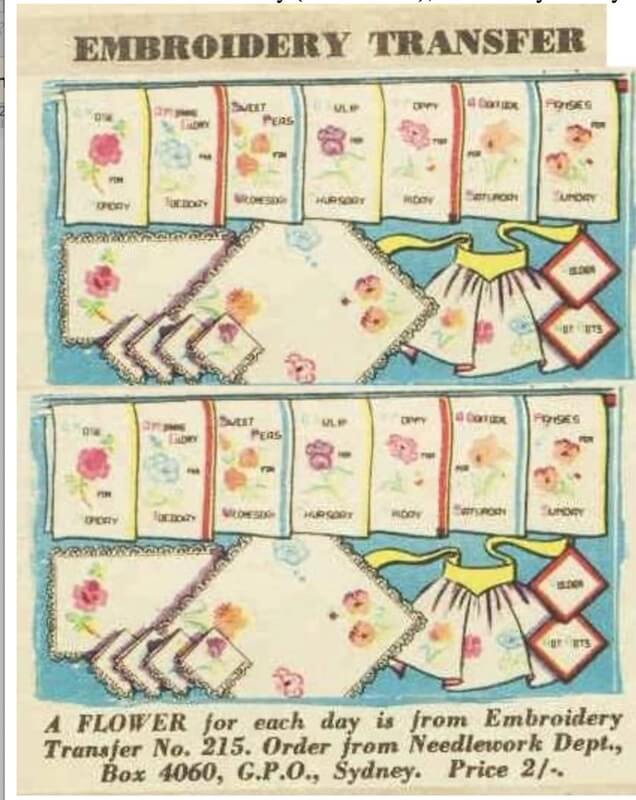

Needlework patterns and the Semco company

From the second decade of the twentieth century Victorian women could purchase embroidery materials from a local company — Semco. Semco began as a small business in Flinders Lane in 1909, but moved in 1911 to the then outer suburb of Black Rock, where the company believed it could provide better facilities for its workers. Semco produced all manner of materials for the needleworker, from patterns, to stencils, embroidery silks and instruction manuals. Its designs for household linen were widely adopted and many households had at least one example on show. A large collection of Semco materials is held by the Sandringham and District Historical Society. Semco and its suppliers also advertised regularly in magazines like the Australian Women’s Weekly.

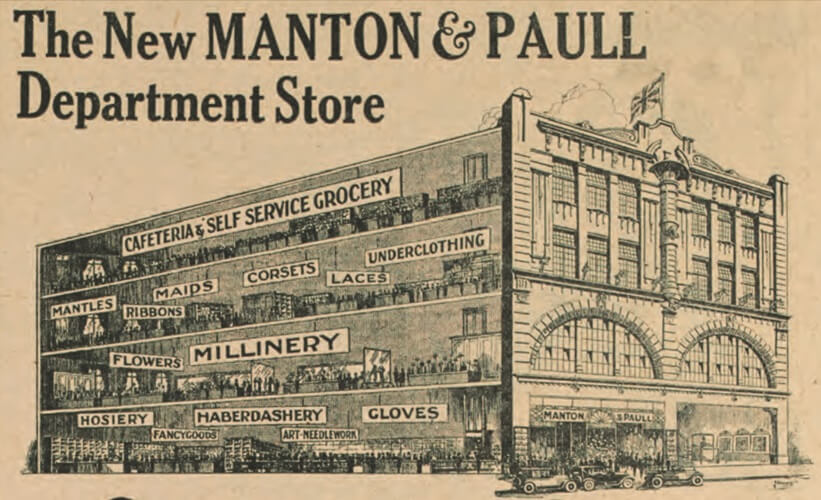

Haberdashery

Women could purchase their fabrics and sewing materials in a wide range of drapery shops, and later in the haberdashery departments of the major department stores. These were large sales sections, often extending over a full floor or more. They offered bolts of cloth in varying materials and quality, and by the twentieth century also offered a large selection of paper dressmaking patterns. Annual sales could often attract large crowds of shoppers, searching eagerly for bargains.

Learning to sew

Most girls were taught to sew by their mothers, or another female relative. But as more girls went off to school and remained there longer, sewing was also taught at school. It was a strictly gendered curriculum. While girls were taught to sew, boys did either canework, or later woodwork/metalwork. This continued into the late 1950s-early 1960s. Many a primary schoolgirl was sent home each year with a (frequently grubby) checked gingham teacloth, decorated in white cross stitch, ‘for mother’!

Pupils of Drummartin School doing craft work 1926

The girls are sewing and the boys doing rafia (basket) work.

Courtesy Museums Victoria

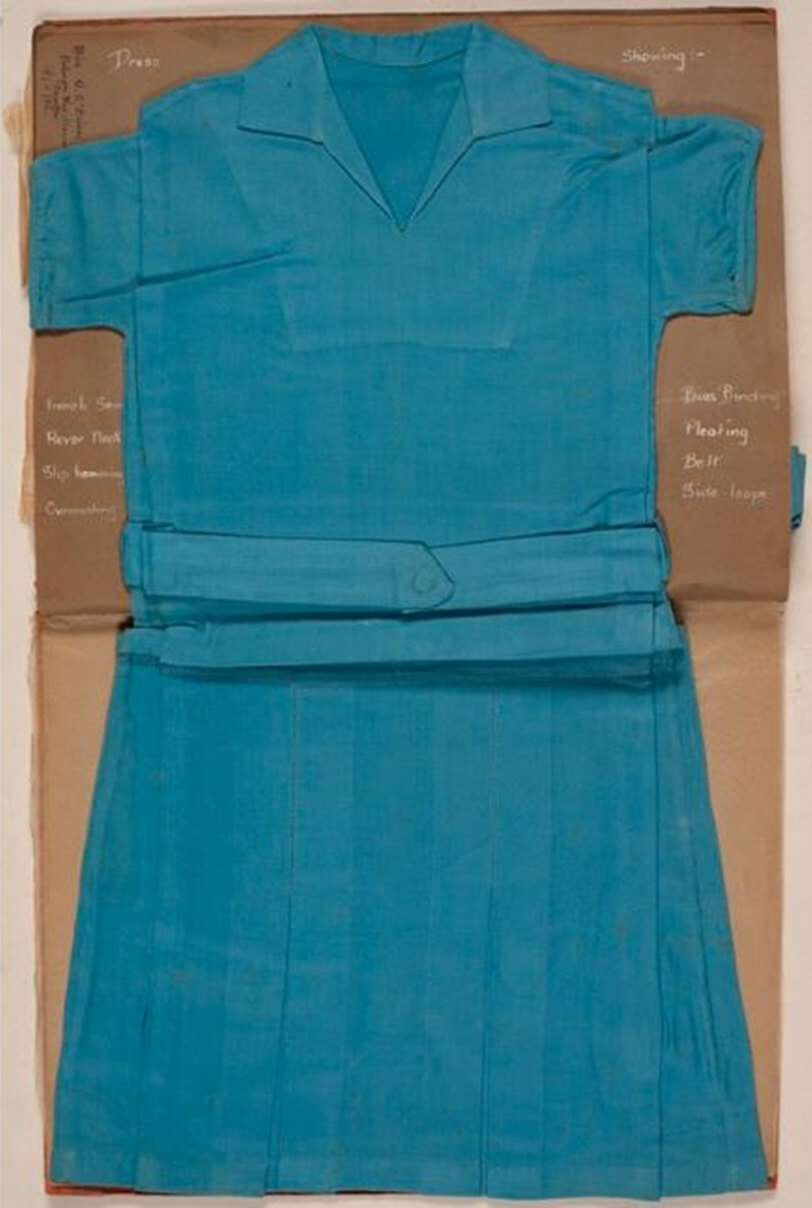

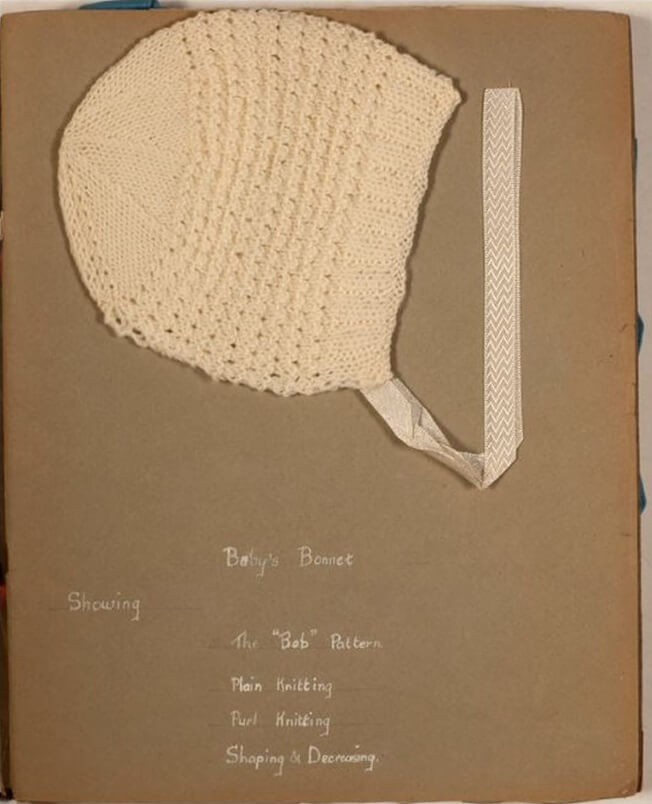

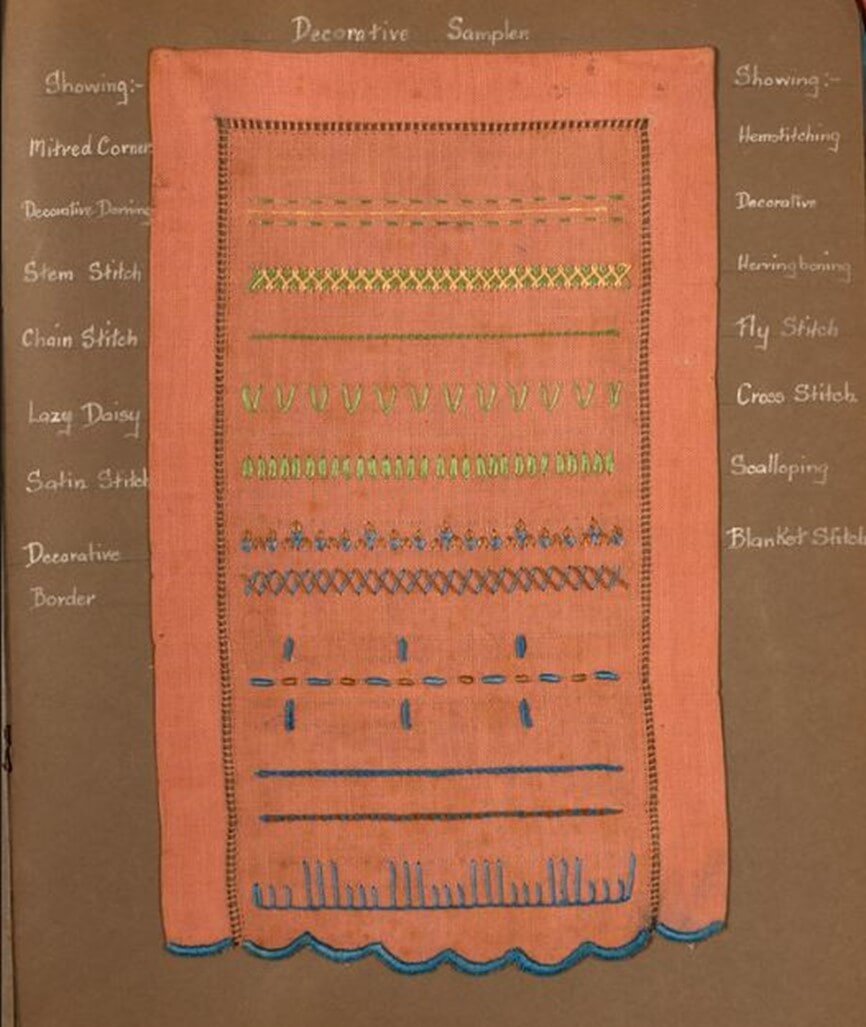

Some primary school girls achieved an extraordinary standard of proficiency in their needlecraft. This sample book was made by Marie George, while a pupil at Kew Primary School in about 1900. It includes this child’s tunic, a pair of closed ‘bloomers’, a knitted baby’s bonnet and a sampler showing a wide range of decorative stitches. Each piece is annotated to indicate the stitching technique demonstrated.

Needlework sample book, made by Marie George at Kew Primary School, c. 1900

Public Record Office Victoria

This gendered division of the craft curriculum continued into secondary school, where girls were taught cooking and often dressmaking, while the boys learned basic wood or metal work. Secondary schools were usually equipped with sewing machines, many of them Singer. By their teens many girls were quite competent dressmakers.

Sewing was seen as an essential female skill until the 1970s. Thereafter it declined in importance in the face of cheap imported clothing and changing ideas about woman’s place. There is now something of a resurgence in both sewing and other handcraft skills like knitting and crochet, but modern needlecraft workers must find most of their supplies in online stores. The huge haberdashery departments of major department stores all disappeared in the late-twentieth century, to be replaced with smaller specialist shops, often in the suburbs.

Further reading

Lorinda Cramer Needlework and Women’s Identity in Colonial Australia. Bloomsbury Academic, 2020.

Lorinda Cramer, ‘Keeping up Appearances: Genteel Women, Dress and Refurbishing in Gold-Rush Victoria Australia, 1851-1870’, Textile Cloth and Culture, Vol. 15, Issue 1, 2017, pp.48-67.

Margaret Maynard Fashioned from Penury: Dress as Cultural Practice in Colonial Australia. Cambridge University Press, 1994.

Rosika Parker The subversive stitch: embroidery and the making of the feminine. Women’s Press, London, 1984.

Kimberly Webber, ‘Romancing the machine: the enchantment of domestic technology in the Australian home’. University of Sydney, 1996.