We now take the indoor flushing toilet entirely for granted. Few of us remember the smelly ‘long drops’ that were once ubiquitous in Melbourne’s backyards. But for most of the nineteenth century, and well into the twentieth in some suburbs, the indoor flushing toilet was a marvel available only to the rich, while the unsewered city was a very unhealthy place to live.

Melbourne’s unsavoury beginnings

The arrival of Europeans at Port Phillip followed closely on the first of a series of health crises in London, then the largest city in the world. Cholera was first identified there in 1831, but its causes were then unknown and medical theory at the time continued to associate disease with ‘miasma’, or bad air, for several decades. It was not until the 1850s and sixties that scientists understood the dangers of drinking water contaminated by sewage. By then the Thames was little better than an open sewer, so much so indeed, that Parliament was forced to close in the summer of 1858 during what became known as the ‘Great Stink’. (For more information on this and other incidents see: https://www.sciencemuseum.org.uk/objects-and-stories/medicine/cholera-victorian-london ).

Unfortunately, Melbourne’s early residents followed a similar pattern. Householders usually dug a hole in their yards to store their toilet waste. It was known as a cesspit or cesspool, and usually had a wooden seat positioned over the top. When the pit was full, they simply dug another. Most households used chamber pots overnight, then emptied them into the cesspits in the morning. If the family was wealthy, this was usually one of the first jobs for the lucky servant each morning. If not, the task generally fell to the wife and mother. In poorer districts many houses might share one communal cesspit.

At first many of Melbourne’s cesspits were unlined, with the inevitable result that sewage seeped through into the ground water and overflowed into the surrounding soil. Since much of Melbourne was built on clay soil, absorption was always a problem. When it rained heavily, or flooded, raw sewage flowed down the drains into the Yarra, or gathered in stinking pools on low-lying ground. For the first few decades Melbourne was little better than many Mediaeval cities in this respect. Poor, working class suburbs like Fitzroy, that were often located on poorly-drained, low-lying land, fared especially badly, as seepage from the wealthier suburbs flowed down into their yards and basements.

Noxious industries also clustered along the river in the inner-city and nearby suburbs, discharging their waste directly into the river. Within a very short time the Yarra was heavily polluted, its once-wholesome water smelly and unpalatable. Since it was the only real source of drinking water for the expanding city, this was a serious health issue. Although some households managed to dig wells, many others were forced to buy their water from water carriers, who drew their supplies direct from the Yarra. This water was expensive, but also increasingly polluted. Enteric diseases like diarrhoea and typhoid claimed many lives, especially in the summer months. The rapid expansion of Melbourne during the early years of the gold rush made the problem infinitely worse, but also attracted adverse commentary from the many lettered visitors attracted by the lure of gold. In 1853 Mrs. Campbell, recently arrived from Quebec, described the Yarra as a ‘filthy little muddy stream’ and she was only one of many. (Mrs. A. Campbell, Rough and Smooth,1865:47) Meanwhile the different authorities debated back and forth about what to do. Everyone wanted a solution, but as often happens, no one wanted to pay for it! Eventually a private company offered to build a reservoir to supply clean water to Melbourne from the Plenty River, with assistance from the Victorian Government. Water from the Yan Yean Reservoir began to supply Melbourne in 1857.

Xmas 1841. How we got our water in the Pree Yan-Yeanite Era, by Robert Russell, 1881

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

At the same time the Government set aside funds to begin constructing a sewerage system for Melbourne, aware of similar plans in other global cities. However, the costs of building the Yan Yean Reservoir, then the largest artificial reservoir in the world, far exceeded estimates, and ultimately consumed the additional funds set aside for a sewerage system. As the windfall from alluvial gold dried up, different public authorities bickered amongst themselves about who should bear the cost of such expensive infrastructure, with the result that nothing was done. This continued for decades.

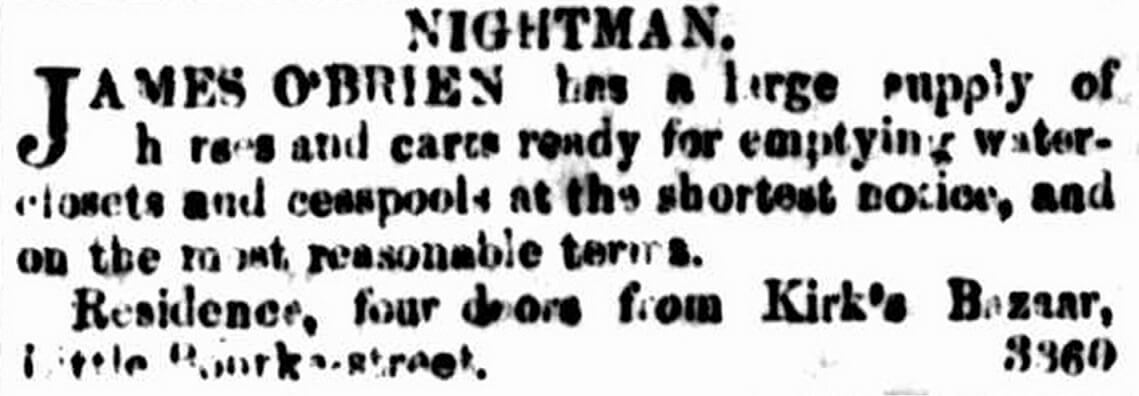

The nightman

As Melbourne’s population exploded during the goldrush years, dealing with human waste became a serious problem. Manure depots were established on the outskirts of the city and nightmen advertised their services to empty cesspits and transport the waste. They were so named because they earned a living removing ‘nightsoil ‘as human waste was euphemistically known. Since it was such a smelly task many nightmen carried out their task at night, though this must have been something of a challenge in Melbourne’s dark streets. Later nightmen routinely emptied pan toilets at night, travelling down the laneways behind rows of houses and accessing the pans placed along back fence lines. Many of these laneways can still be seen in older suburbs. You can read more about Victoria’s nightmen here: https://www.oldtreasurybuilding.org.au/lost-jobs/on-the-road/the-nightman/ .

However, the services of the nightmen were at the expense of householders and not all were willing to pay. Overflowing and leaky cesspits continued to be a hazard and the manure depots themselves soon filled up. It was assumed at first that market gardeners would pay to remove the manure for use on their vegetables, but the demand never approached the supply. It is best not to think about the consequences of using untreated human waste on food gardens, but this practice continued well into the 1870s, long after germ theory was widely known and accepted. Ironically, the availability of (cheap) water in the city only made the problem worse, as householders often ran water into their cesspits to dilute the waste, causing them to overflow even more.

The water closet

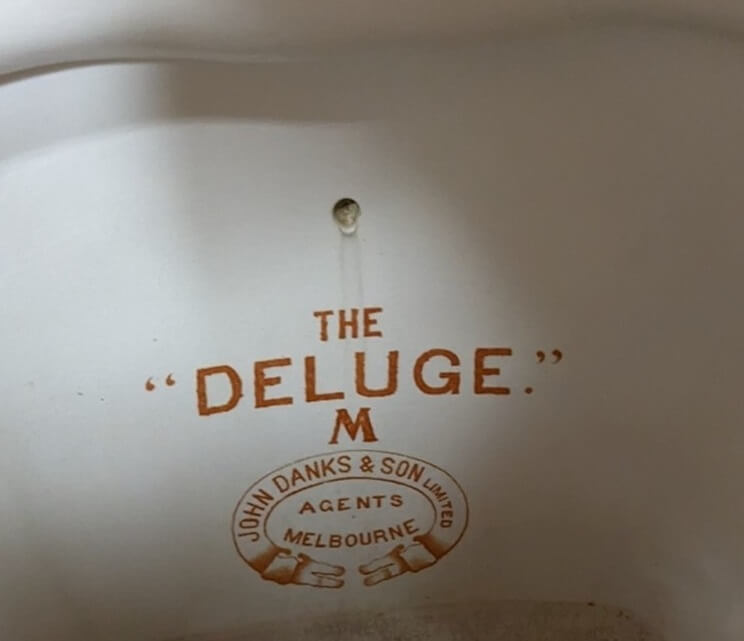

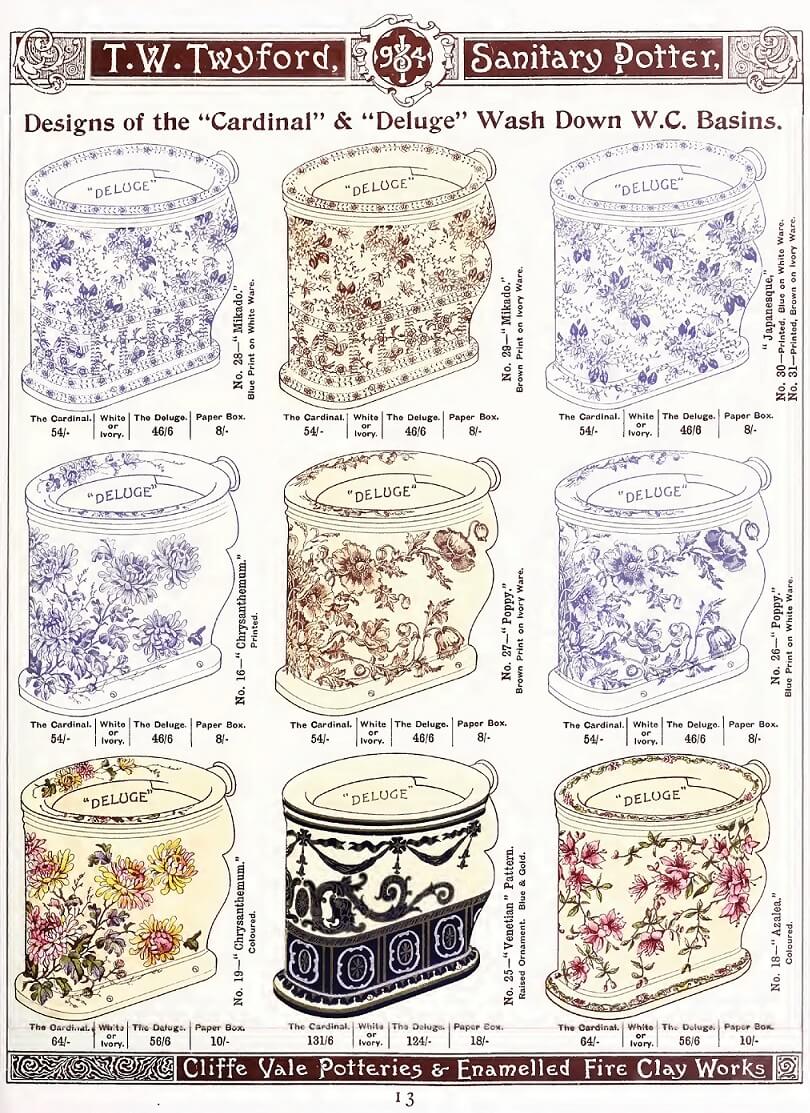

Wealthy people also began to invest in water closets, the precursor of the modern flushing toilet. Water closets consisted of a toilet bowl with a water tank above. A chain operated a lever to release the contents of the tank into the bowl below, flushing waste into a household drain. At first these drains ran into individual cesspits, where they exacerbated the problem of overflowing pits. Early WCs were nowhere near as efficient as later models, since the water was initially released too slowly to be really effective, but families wealthy enough to install them were at least spared the necessity to traipse outdoors in all weathers. The bowls of these early water closets were often richly decorated. Perhaps the designs were designed to distract from the purpose of the bowl, but porcelain bowls, decorated in coloured, underglaze transferware, were common into the early-twentieth century. Some were decorated both inside the bowl and outside, while others, like the example included in the exhibition, were plain on the outside, probably intended to be enclosed in a wooden case to resemble a piece of furniture.

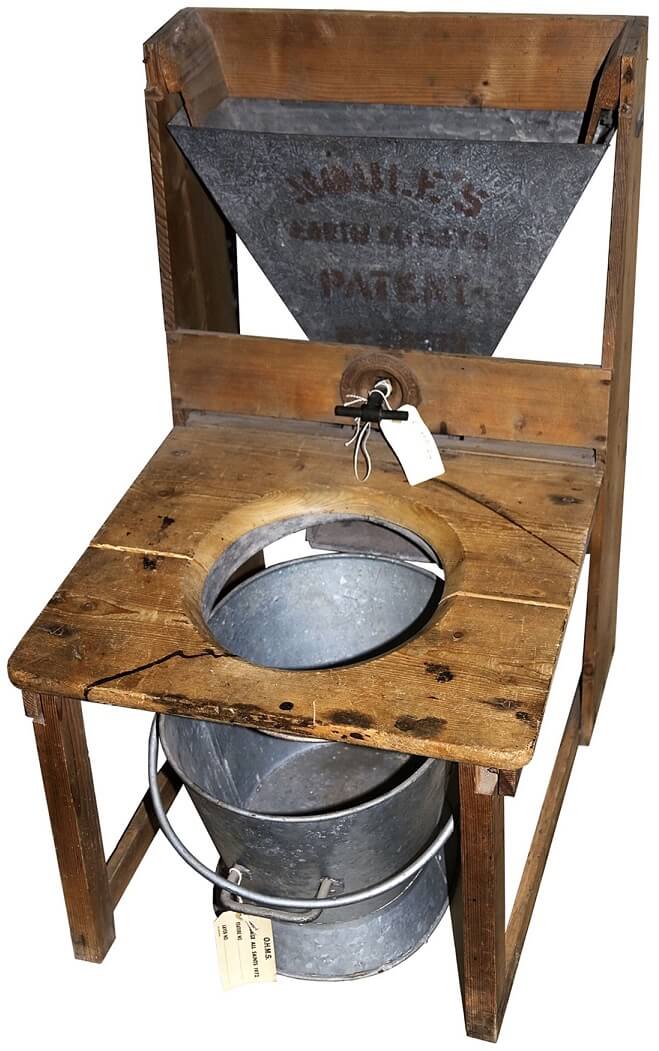

In 1861 the Melbourne City Council at last took action to try to regulate leaky cesspits, requiring all householders to construct either clay-lined, bluestone pits or to insert new ‘barrel’ pits inside existing pits to make them waterproof. Householders could also be fined for allowing their pits to overflow. An Inspector of Nuisances was appointed to investigate reports of leaking pits. The invention in 1860 of a new ‘earth closet’ also promised to assist in reducing the pervasive smell of urban household waste. The earth closet was an ingenious invention, consisting of a wooden seat over a bucket, with a box alongside containing earth or ashes. Users sprinkled a scoop of earth into the pan after use.

Earth closet above and water closet below

An improved version featured a hopper above filled with earth or ash. When a handle was pulled, a layer of earth was released into the bucket, which was emptied periodically by a nightman. The earth or ash was intended to help contain odours, which were still thought to cause disease. Large numbers were installed in Melbourne from the mid-1860s, although in a characteristic failure of leadership, the Higginbotham Government rejected the Chief Medical Officer’s advice to make them compulsory in its 1867 revisions to the Health Act. (Age, 11 February 1867, p.5) Cesspits continued to overflow as a result, with waste from the government’s own premises some of the worst offenders. For an account of the makeshift toileting facilities at the Old Treasury Building see: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GPApHdhKa94

From the 1860s it was increasingly common for families to have a dry pan toilet or earth closet located on the back fence line of the property, where a nightman would empty it weekly. This went by various names. One of my forebears, describing ‘Our Home In Australia’ in a letter written to his mother in 1860, included a little sketch of the back yard, showing their facility, marked ‘C’ on the sketch and with two exclamation points over what is presumably the seat. ‘C’ probably stood for convenience, though in his letter he also calls it the ‘house of ease etc. etc. etc!’ in a rather coy attempt at humour. (Elliott, Our Home in Australia, p.76) Most people simply referred to the privy, a much older term. Later the slang term ‘dunny’ seems to have evolved in Australia and New Zealand, but its origins are obscure.

By the 1880s the design of water closets had improved markedly, making them much more efficient at clearing waste from the bowl. This was achieved by releasing a large volume of water in a rush, and indeed early WCs used a great deal of water. We know a fair bit about one such WC that was installed for the Governor’s use in the Old Treasury Building. This was highly decorated inside and out and was apparently the top of the range at the time. It was manufactured by T.W. Twyford of Hanley in England, sometime between 1889 and 1896, and was known as the ‘Deluge’, from the three gallon ‘rush’ of water it released. Twyford’s catalogue promised that the ‘Deluge’ was ‘one of the cleanest flushers you can buy’. Three gallons (11.3 litres) is a lot of water. By way of comparison, modern ‘smart’ toilets now use between 3 and 4.5 litres per flush, so we begin to see why Melbourne’s cesspits continually threatened to overflow.

One of Twyford’s catalogues still exists from 1896, showing the wide range of patterns available for purchase at the time.

Source: Internet Archive

Marvellous Smellbourne

By the late-1880s Melbourne was booming. Grand new buildings sprouted throughout the city and even working people aspired to home ownership in the expanding inner suburbs. When a visiting English journalist coined the phrase ‘Marvellous Melbourne’, the locals adopted it proudly. But beneath the façade of growth and plenty, dirt and disease abounded. Typhoid was rife, along with other enteric diseases, and the city literally stank. Melbourne’s detractors dubbed it ‘Marvellous Smellbourne’ to the anger of prominent Melburnians. Finally, the government was shamed into doing something about it after a damning Select Committee Report into the Sanitary Condition of Melbourne. The Melbourne and Metropolitan Board of Works was created in 1891 and began the slow process of constructing a water-borne sewerage system. The first houses were connected in 1897.

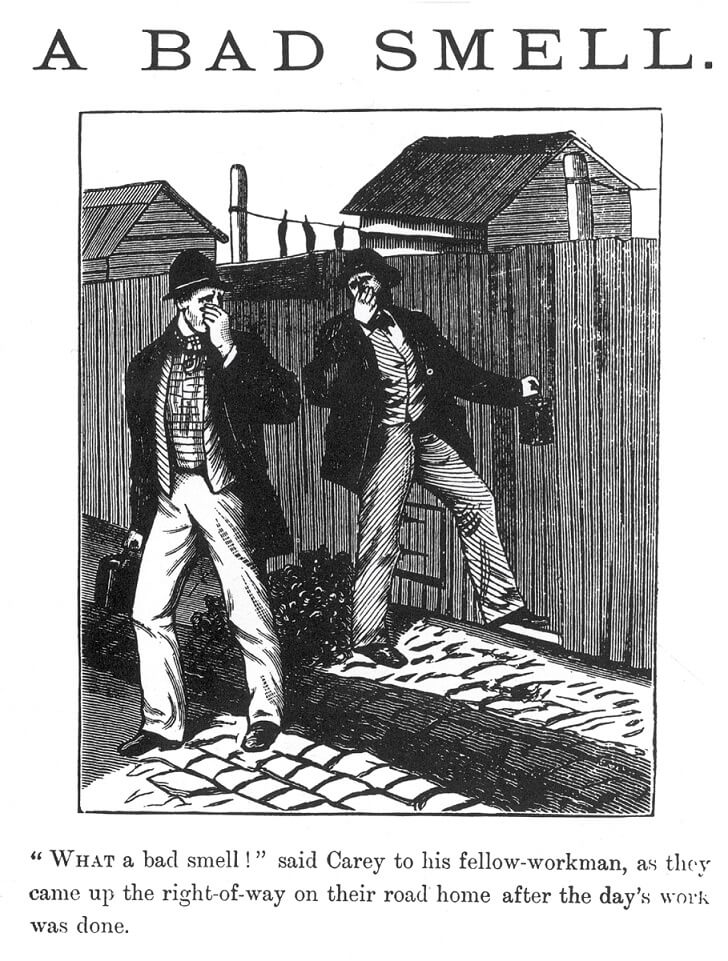

Illustration from an Australian Health Society pamphlet, August 1880

Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia

Indoor water closets

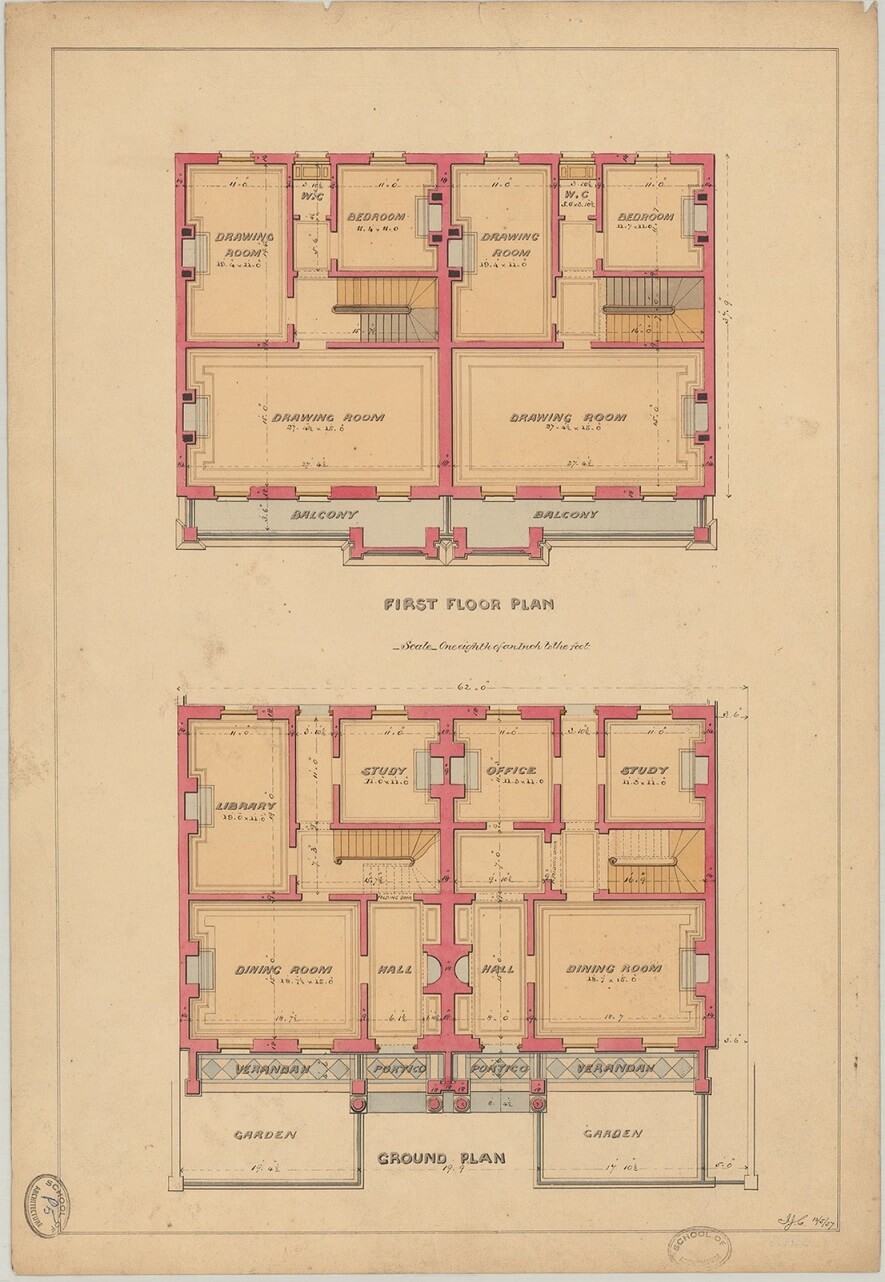

Although most ordinary folk accepted the need to scurry outside to use the toilet, wealthy people installed water closets inside their houses from as early as the 1850s. Architect JJ Clark, who designed the Old Treasury Building, created plans for several dwellings in 1857 showing WCs located upstairs near bedrooms. But even in the 1880s it was quite common to design villas with no obvious WC, or with the WC located in the backyard, often near the laundry. We included some of these plans in the discussion of ‘A Home of Our Own’.

JJ Clark, Plan of residences, 1857.

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

What these house plans do indicate however is that by the late-nineteenth century it was common to include a bathroom under the main roof.

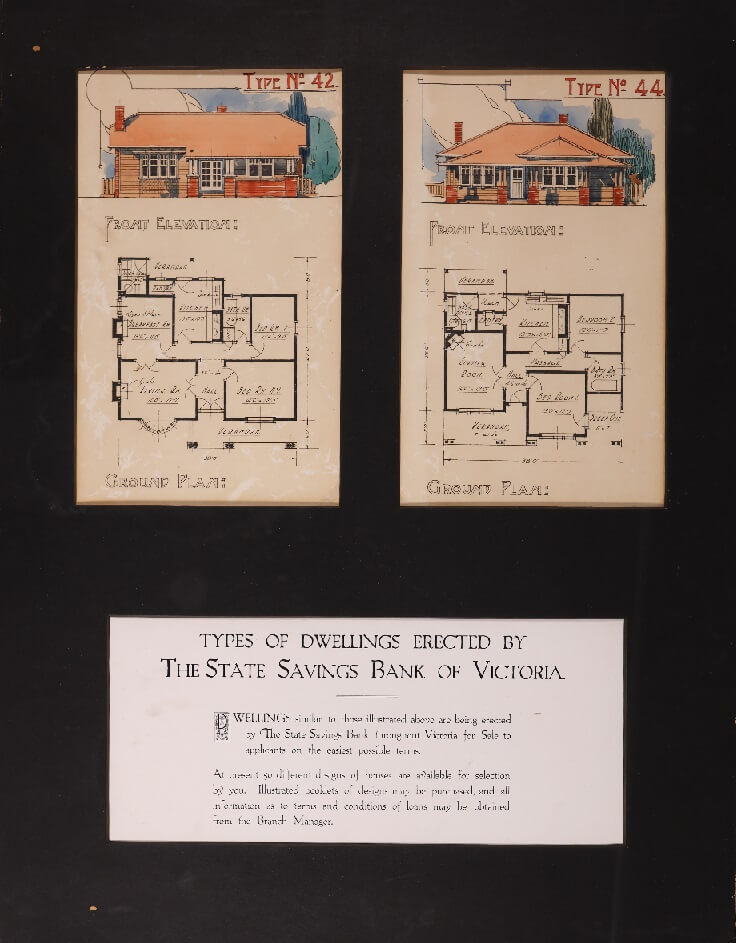

A toilet that flushed

By 1910 most homes in inner metropolitan Melbourne were connected to the sewerage system and could install a toilet that flushed. But that did not mean that the WC migrated indoors. As the many designs created by the housing department of the State Bank of Victoria show, it was still very common to locate the WC off the back porch or verandah of a home, usually paired with a ‘wash house’ or laundry. What is especially interesting about these plans, is that they usually indicate that access to the WC was not directly through the porch or wash house, but via an external entrance, so that users were still forced to go outside. A visit to the toilet often continued to involve an encounter with Melbourne’s weather! Even quite grand house designs might show this feature, suggesting lingering unease about locating the toilet inside the house.

Types of dwellings erected by the State Savings Bank of Victoria, undated but probably late 1920s-1930s.

Reproduced courtesy Public Record Office Victoria

In the post-war period this gradually changed, though not entirely. Even in the 1960s, as houses began to increase in size and many plans incorporated a WC under the main roof, some access continued to be external. But by the 1970s that was obsolete, as houses began to include not one but two bathrooms and associated WCs. The changes in design offered by AV Jennings are especially instructive in this regard. You can read about them here: https://www.oldtreasurybuilding.org.au/belongings/av-jennings/.

While most inner suburbs were connected to the sewerage system by the early-twentieth century, it was a very different story further out. Despite good intentions, the sewer network spread outwards slowly, and nightmen continued to ply their trade as late as the 1980s in some areas. Others made use of septic tanks, which are still in use in many regional areas, although with flushing toilets attached.

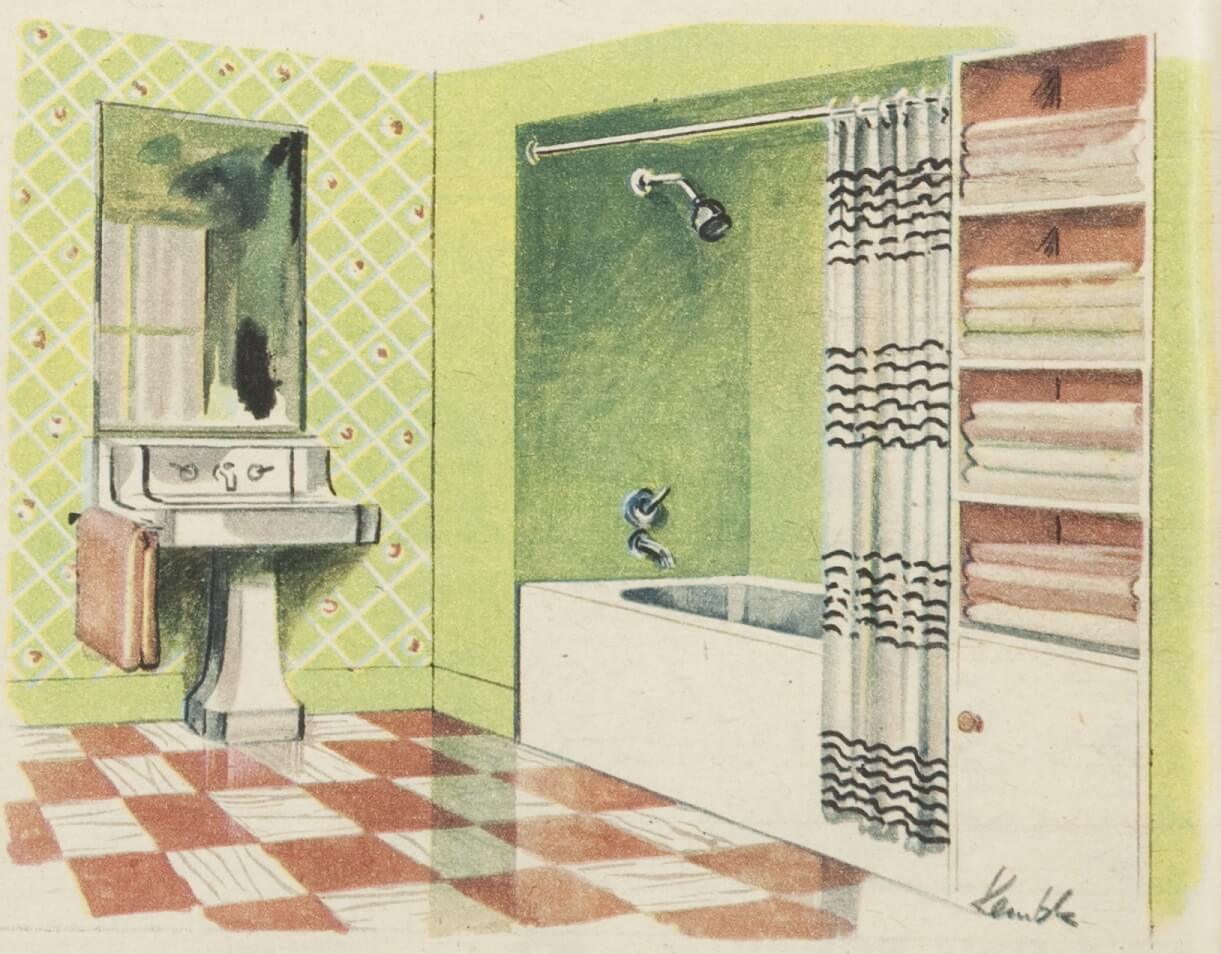

Toilet fashion

The fashion for decorative toilet bowls retreated in the twentieth century in favour of a preference for pure white, or various pastel shades. Pale pink and green were quite popular colour schemes for bathrooms during the 1920s and thirties, continuing into the post-war period, sometimes with matching bath and toilet sets. They were often paired with terrazzo floors, only to become hopelessly out-of-date in their turn. Tiled floors were increasingly common from the 1960s along with extensive wall tiling, as shower recesses replaced shower heads over baths. These now come in a bewildering range of shapes, sizes and patterns.

A bold design for a bathroom, Australian Women’s Weekly, 4 August 1954

Image courtesy National Library of Australia

Toilet paper

Toilet paper is another essential of modern life, so much so in fact that rumours of shortages during the recent COVID lockdowns led to panic buying in many Australian cities. In some supermarkets the shelves were stripped of all stock, although there was never a real problem with supply. In vain, authorities urged customers to show restraint, but being without toilet paper was evidently just too terrible to contemplate!

Bare supermarket shelves, Woolworths Melbourne 9 March 2020

Photographer: Christopher Corneschi

Wiki Media

Such panic buying would have bemused our forebears, whose own solutions were generally home-made. All sorts of materials were used over the centuries, including scraps of rag, wool, leaves, or bark, but from the nineteenth century the most common material was newspaper, cut into squares, threaded onto string, and hung from a hook or nail. This was often a job for children. Shop catalogues were also used in this way, once any ordering was complete. But some things were apparently sacrosanct. Melbourne resident, Janet Hicks, remembers cutting up newspapers and the redundant phone book to use as toilet paper in the 1950s, but the Australian Women's Weekly was off-limits: it was considered ‘too precious to be used as toilet paper’.

Toilet paper was also made commercially in the nineteenth century, when it was sold in pharmacies as ‘therapeutic paper’. The paper contained aloe or oils to help prevent sores, but it was very expensive and was far beyond the means of most ordinary people, especially when there was a far cheaper alternative to hand. By the 1930s toilet paper was sold in rolls in Australia and we showed several surviving rolls in the exhibition, sourced from the collection of the Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences. But once again, it is difficult to know whether this was bought by ordinary householders or was considered a luxury item. Certainly, by the 1950s the use of toilet paper seems to have been well established in indoor, middle-class facilities, but older methods evidently persisted, especially in backyard toilets.

Toilet rolls made in England and Australia between 1930 and 1942.

Courtesy Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences

Contemporary Australians now consider efficient, flush toilets to be an essential of modern life. Many homes are furnished with not one, but two or more, all plumbed into either the sewerage system, or a septic tank. Modern toilets also come with a range of additional facilities, like automatic ‘soft closing’ lids and ‘smart’ flush mechanisms that use far less water. Some have seats that are heated in winter, although the bidets popular in France and Japan never seem to have caught on in Australia. Toilet paper is also available in a range of patterns and varies in thickness from single ply, to double, triple or even quadruple ply. It is all a far cry from the earth closet on the back fence with its wad of newspaper squares!

Further reading

Bernard Barrett The Inner suburbs: the evolution of an industrial area. Carlton, Melbourne University Press, 1971.

Graeme Davison, ‘Down the gurgler: Historical influences on Australian domestic water consumption’, in P. Troy (ed.) Troubled Waters: Confronting the Water Crisis in Australian Cities. Canberra, ANU Press, 2008, pp.37-65.

Walter T. Hughes, ‘A Tribute to Toilet Paper’, Reviews of Infectious Diseases, Vol. 10, No. 1, January – February 1988, pp.218-222.

T.W Twyford, Twyford’s Catalogue of Sanitary Specialities: in porcelain, earthenware and porcelain-enameled fire-clay: sanitary appliances & fittings. Cliffe Vale Potteries, Hanley, 1894.

Lawrence Wright Clean & Decent: the fascinating history of the bathroom and the water-closet. London, Penguin, 1960.