In the past childhood, for many, was a time of work, not play. Children worked on family farms at harvest time and regularly milked the cows. In the city young boys ran messages, or swept the roads. Others worked on the streets, selling newspapers, flowers and matches.

Most young girls worked at home, helping their mothers. They cleaned the house, washed-up and minded their young brothers and sisters. Girls also worked as domestic servants in other people’s homes, sometimes starting work as early as 6am and working until 10pm. As children grew up they were expected to contribute to the family income. Until the 1870s education was a luxury for the well-off.

On the Factory floor

Children once worked, often with their parents, in Melbourne’s factories. They were ideal factory workers; likely to respond to punishment and unlikely to organise and strike against poor pay and working conditions. They were also smaller and could do the fiddlier tasks.

Children worked in a range of industries — soap and candle works, flour mills, sawmills, canneries, boot factories and brickyards — performing a variety of tasks. In clothing factories, boys worked as ‘floor boys’, whilst girls carried out the low skill job of ‘tacking’. In the textile mills, children worked as ‘piecers’, repairing threads broken during weaving. Large numbers of boys and girls worked in the tobacco, snuff and cigar factories in Melbourne, ‘with about sixty or seventy children to every twenty men’. The print industry used child labour, with 30 boy compositors on the staff of The Herald and World newspapers in 1883:

… boys of the most tender years are employed at excessive and unreasonable hours… and they are compelled to work every night in the week… from three or four in the afternoon till about three the following morning…

Children as young as eight worked on the factory floor, even after this was illegal. One mother confessed in 1884 that she had three children working in a factory — ‘seven years and three month… eight years, ten months, and one twelve years’. Some employers, it was reported, ‘took them… at any age’.

The children worked long hours, typically a ten-to-fourteen-hour day, for very little pay. On average, children were paid about one third of the adult male rate. A child in a rope works in Melbourne, for example, earned 7s for a fifty-hour week in 1884. An adult male earned between £2 and £2 and 10s. Some employers did not indenture their juniors and if they were ‘naughty’, their wages were docked.

Young children endured harsh conditions, with reports of children ‘crowded into small rooms which are suffocating in summer and intolerably cold in winter.’ In one factory it was noted that there were ‘seven men and four boys’ in a small room with no ventilation. Children were put in charge of steam boilers and other powered machinery, sometimes with disastrous consequences. The Advertiser reported in 1899 that ‘children under 10 years of age were employed in suburban factories, and it is a common occurrence for them to have their fingers taken off in the machinery.’

Many doctors expressed grave concern about the effects of factory work on children’s health. One recalled:

a little girl was brought to me three days ago by her mother, a little worn-out looking thing. She had been twelve or eighteen months in a factory already, and she is only thirteen now. She is like a little old woman, pale and shrivelled, and suffering from palpitation of the heart.

Diseases such as typhoid, diphtheria and whooping cough spread in unsanitary factory conditions. Children were ‘forced to squat in cramped spaces’, or made to stand all day, causing physical deformities such as curvature of the spine.

Children’s education suffered, many of them ‘skipping’ school to attend work. More concern was shown for their moral health. Much was written about the ‘evils’ of night work, especially in the printing trade, and the ‘mixing of the sexes’:

… in some of the clothing factories there was not the slightest attempt at separation of the sexes, and the gross familiarity which existed between them led in some cases to seduction or open immorality.

Tobacco factories were particularly castigated:

The description given… of the character of boys and girls in the tobacco factories was most repulsive, their ordinary conversation being of a very filthy nature. Most of the lads engaged in these places both smoke and chew, and these practices are winked at by employers in order to induce them to stay at their work.

From the 1870s there were efforts to regulate and outlaw child labour. In 1872 the Education Act was passed, making school attendance compulsory for children between the age of six and 15. After the Act it was difficult for children to work, but not impossible. Parents appear to have colluded with employers to falsify the ages of their children.

In 1873 Australia’s first Factory Act was passed. Under the Act, women and girls were not allowed to work for more than eight hours per day in a factory. The Factories and Shops Act in 1885 brought about further changes. No person under the age of thirteen could be employed; no person under the age of fifteen [13–14 years] could be employed unless they had been educated to the standard required by the Education Act of 1872; and no person under the age of sixteen could be employed without a certificate of fitness for employment from a medical practitioner. All factory workers under the age of sixteen were restricted to a forty-eight-hour week.

Evasion of the law, however, was commonplace, while smaller factories were excluded from their provisions. The Argus reported that many factories failed to comply with regulations, citing overcrowded workrooms, poor ventilation, insanitary facilities, and long hours worked by young children. Poverty drove the use of child labour. In 1910 a number of parents were fined in a Port Melbourne court for not sending their children to school. The parents pleaded hardship and the need for family income.

Living as we do in a relatively affluent society, it’s hard to visualise the conditions some children endured, and the toll it took on their health and intellectual development.

Sheet Iron Department, Sunshine Harvester Works, by unknown photographer, c. early 20th century

Reproduced courtesy Museum Victoria

The Sunshine Harvester works, owned by H. V. McKay, produced farm machinery, including the famous Sunshine Combine-Harvester. By the 1920s it had a workforce of over 2,000.

The sheet metal department employed both skilled tradesmen (sheet metal workers) and assistants, including boys who began as ‘dolly-boys’. The dolly boy’s job was to place rivets in holes, while others hammered them in place. It was loud, dangerous work.

Most of the work done with the dolly was in the grain-box which was over the top of the wheel on the header, and all the grain went into the box… The boy had to get in the box, surrounded by iron, finished with an iron roof, he had a little hole to get out of… and he’d get a handful of rivets, he’d put a rivet in a hole, put the dolly on it, then the bloke outside – Bang! Bang! Bang! – with the hammer. Then while he was finishing off, the boy’d have to get the next one ready and of course, sometimes he might be a bit slow or just learning and the bloke out outside’d go bang! And the boy’d have his finger on it… Most of us started as dolly-boys and we’d have to put in about 600 rivets in an eight-hour day, all day, over our heads, laying on our backs… And this is the basis for a lot of industrial deafness… In those early days when we’d come out and our ears were ringing at the end of the day being in a box all day.

-Recollections of Clem Buckingham, Roy Roberts and George Higgins in R. Faulkner, ed., Duty Noble Done: Sunshine Harvester Diary, 1897, Melbourne’s Living Museum of the West, Footscray.

Premises, staff and family of W. Davies, Boot and Shoemaker, Castlemaine c. 1860

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

The bootmaking trade was said to be ‘overrun with boys of tender years’. Some factories, it was reported, employed ‘14 boys to one or two men’. The industry was renowned for flouting labour laws. In 1887 George White, a bootmaker in Richmond was charged for employing children under 15 years of age who had not been educated to the standard required by the 1872 Education Act. Apprentices to the trade were particularly vulnerable. The Argus reported:

Sir, let any gentleman visit the factories, and he can see the number of small boys squatted down boot closing, who should be at school according to the compulsory clause of the Education Act; and let him also inquire if all these boys are properly apprenticed to the trade, and how many of them are receiving wages. He will find that none are bound, and only one-third on wages, and the other two-thirds will get wages in a month or so.

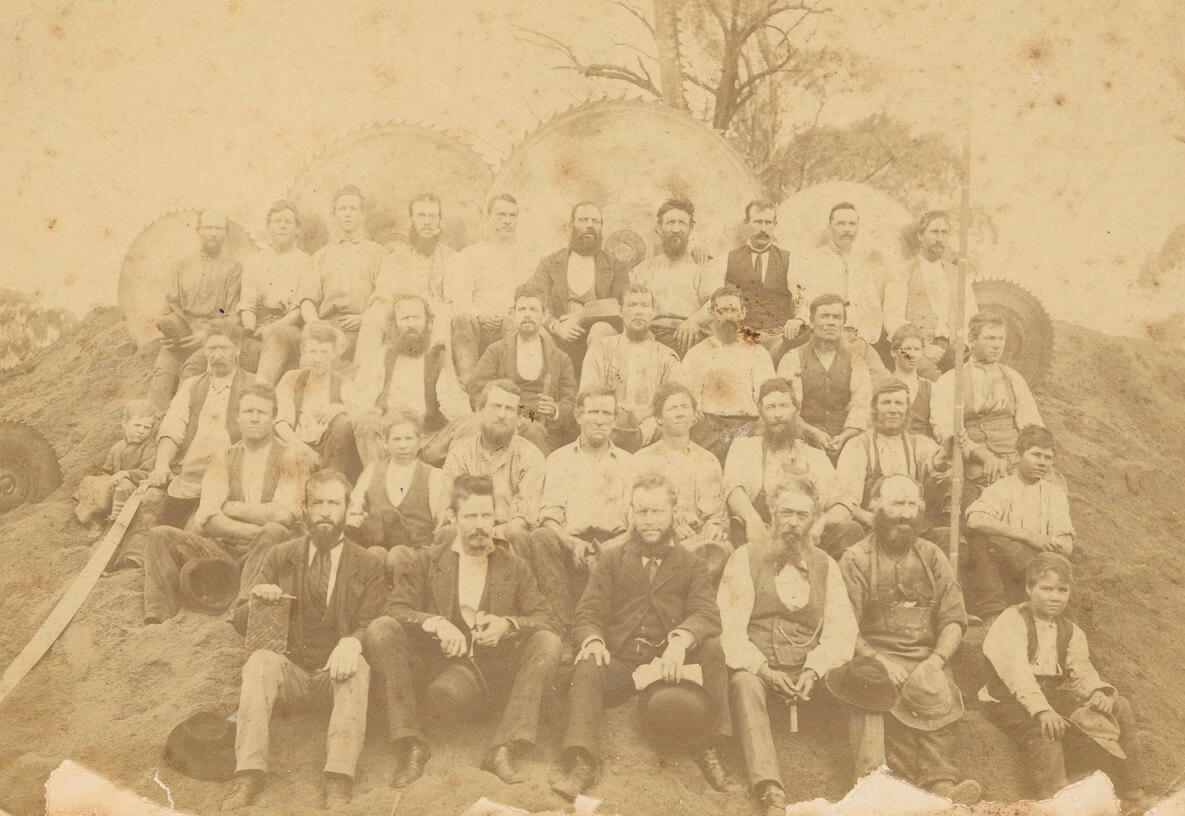

Men and boys working at sawmill, Victoria, by A. Gye, photographer, c,1900

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

Young boys were in the workforce of this sawmill in Victoria in the early twentieth century. It was a dangerous, noisy environment for children.

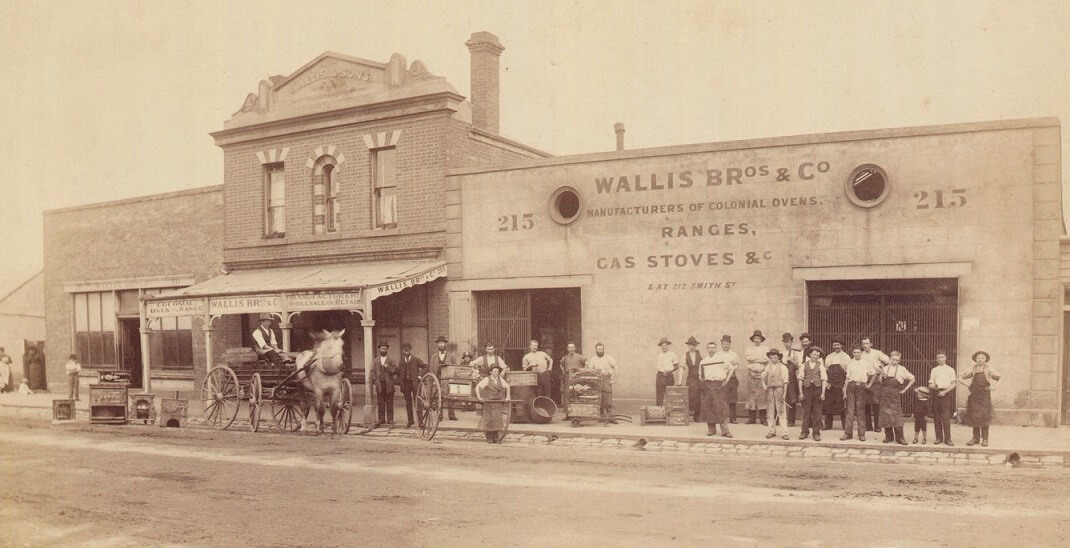

‘Wallis Bros & Co. Manufacturers of colonial ovens, ranges, gas stoves’, by Charles Rudd, photographer, c. 1884

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

A line of workers, including a number of young boys, stand outside the factory of Wallis Bros & Co., in Smith Street, Collingwood. One of the young boys holds a hand-cart at the curb.

Boys of 14 to 16 years of age were employed, who had to stand on boxes to reach up to their cases. These boys worked from 7 in the evening to 2 or 3 in the morning, and came down again in the afternoon. In one of the offices were a number of little boys – mere children. The boys could not stand it, and were always ill.

-The Ballarat Star, 30 October 1885

We think that the young, at least, should not be allowed to become victims to the cupidity of unfeeling employers; that they should be spared the evils which are inseparable from the calling of a compositor engaged at night-work; and that they should not be called upon to suffer the fiery ordeal until their manhood is developed.

-The Argus, 17 February 1882

From 1450 to the late-nineteenth century, the printed word was set one letter at a time. A compositor stood at a tilted shelf, or ‘case’, selecting individual letters to make up a line of type — the process repeated to form a page. The job was relentless, with long hours and few breaks. Most compositors began as apprentices, and several can be seen in this photograph.

Composing Department at Sands & McDougall Limited, Melbourne, by unknown photographer, 1896

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

Much was written about the ‘great evil’ of the printing trade, and its ‘continuous employment of boys of tender years’. In fact, some of the regional daily papers were entirely worked by boys. The Argus reported in 1880 that ‘lads’ employed by the Sandhurst and Geelong morning papers ranged from 12 to 20. They were forced to work six nights per week, ‘from about 4 p.m. till about the same hour next morning’.

The Factories and Shops Act in 1885 contained provisions regulating the employment of young people in night work and in the printing industry. It was, however, difficult to police and the practice continued. Children were, after all, cheap labour.

On the Street

Children also worked on the street, selling flowers, fruit or cheap goods from handcarts. Others shined shoes at the gutter’s edge. Pennies could be earned holding the reins of a horse for a gentleman or catching rats for the council — it was tuppence per rat in 1902. (Not a task likely to appeal to children today!)

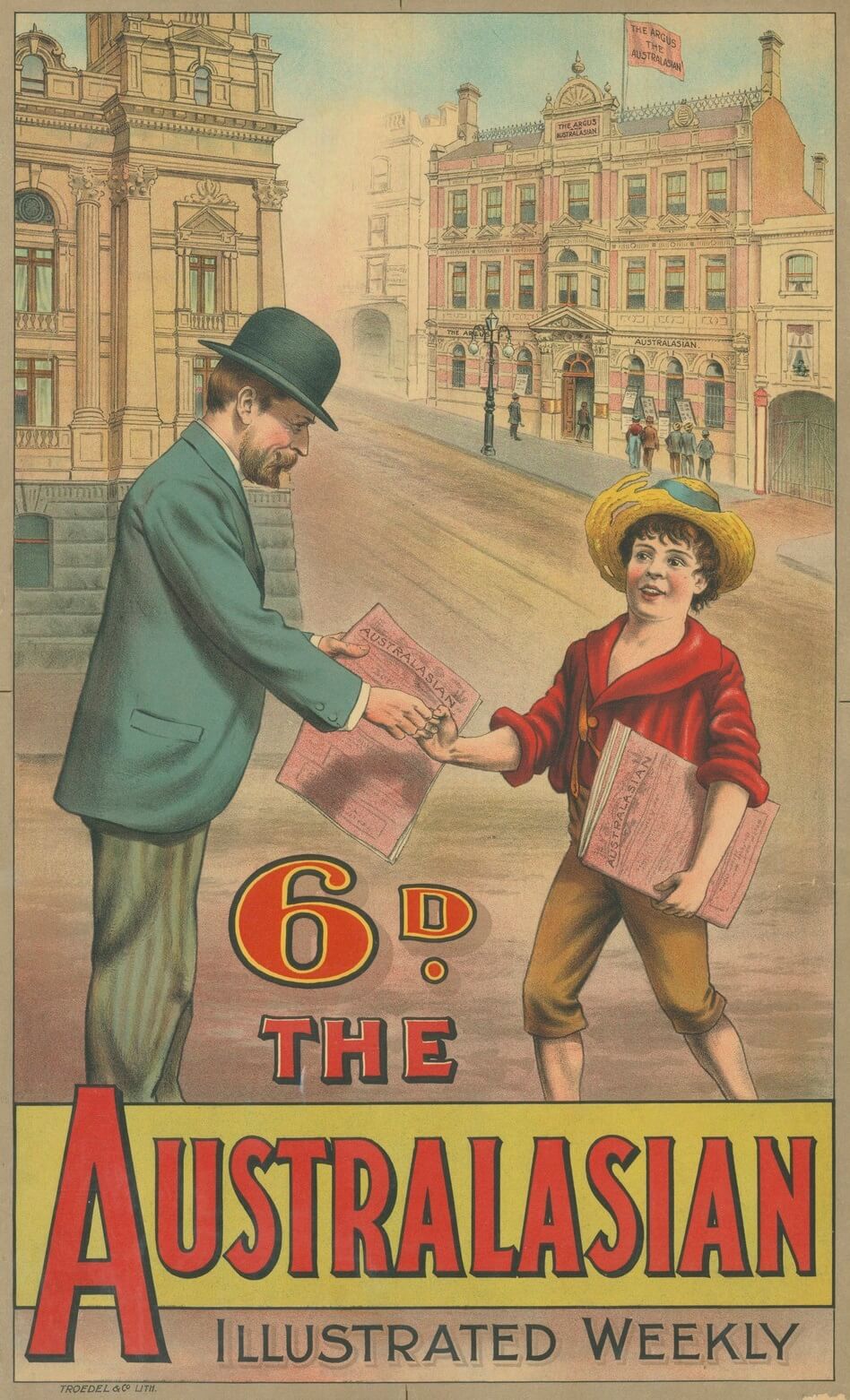

Newsboys (rarely newsgirls) were a common sight on city streets from the mid-nineteenth century. The boys stood at street corners, tram stops, or ‘Under the Clocks’ at Flinders Street Station, calling the headlines. Many were wretchedly poor and homeless; some supported single mothers and their siblings. Boys as young as seven went to work!

Life for a newsboy was hard. Sometimes he worked 15 hours per day — rain, hail or shine — and the newspapers were heavy. A stack of 50 papers weighed around 10 kgs, a substantial weight for a young boy.

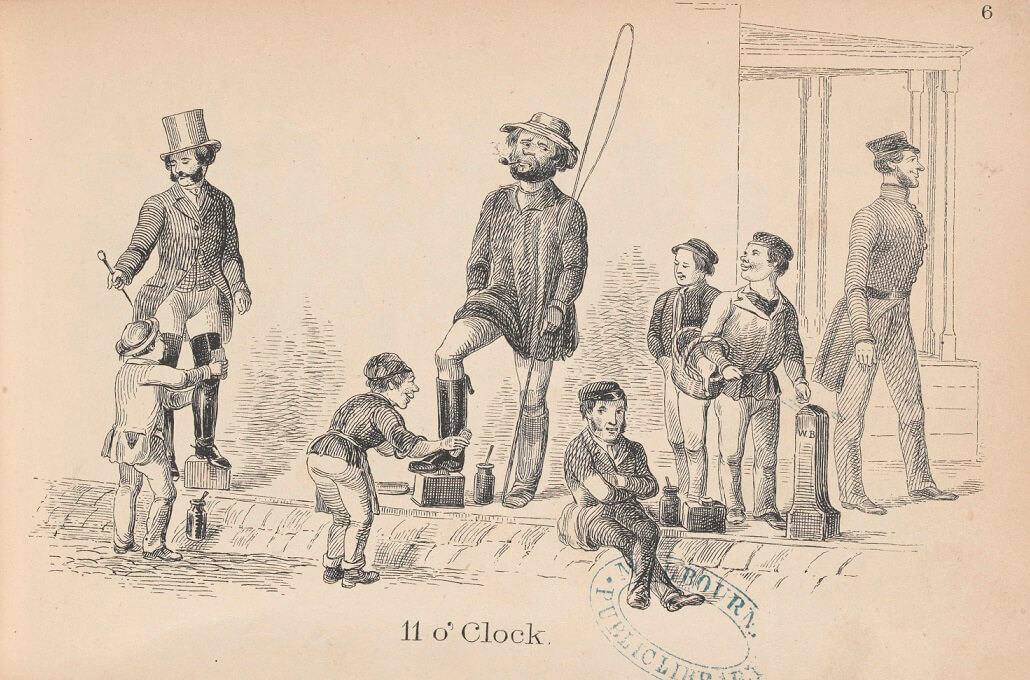

Children bootblacks, in ‘11 o'Clock’, by Henry Heath Glover, artist, 1857

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

Bootblacks were a common sight on Melbourne’s streets, appearing from the early 1850s. Originally a trade practised by children, by the late-nineteenth century, older men had taken their place.

Horses provided a more lucrative, if smelly employment. Prior to motor vehicles thousands of working horses in Melbourne pulled carts, cabs and carriages. These horses produced a lot of manure and young boys were employed by the City Council to pick it up before it dried and scattered. Officially called ‘orderlies’, they were known as ‘Scoop-boys’, ‘Broomies’, ‘Sweepers’ or ‘Block-boys’. Many working-class families eagerly sought the work for their sons, as a good ‘Broomie’ could earn about £1 per week.

The job carried some risk. The boys darted between the busy city traffic with their ‘scoops’ and accidents were common. On 4 May 1888 an orderly fractured his leg when run over by the Hotham Horse Bus. In 1904 David Wilson was ‘jammed between two wagons’ and George Hendy was run down by a delivery cart when working the corner of Collins and Elizabeth streets. Despite the danger, scoop boys performed a valuable service, working well into the 1920s. Their function disappeared as cars replaced horses.

With the street as their workplace, children were particularly vulnerable to hazards, including predatory adults, vehicular traffic and theft. They were exposed to the vices inherent in cities, such as prostitution, gambling, drunkenness and crime. Their longer workdays prevented their schooling.

By 1925 street trading had been regulated. Boys under the age of 14, and girls under the age of 21, were prohibited from trading; no longer allowed to sell newspapers, matches or flowers, clean shoes or sing and perform for profit.

Young flower sellers on Princes Bridge, by unknown photographer, 1903

Reproduced courtesy Italian Historical Society & Museo Italiano

A young flower girl, printed in the Illustrated Australian News, 31 March 1888

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

Flower-selling was one of the few options for young girls to help support their families.

Street work was dominated by boys. Some girls took part, usually selling flowers or newspapers, but it was generally frowned upon. Girls were considered more vulnerable, especially to ‘moral corruption’.

Earnings varied. According to The Argus flower boys in the 1890s pocketed from 5 to 15 shillings per week. Children of course earned much less than adults. Even an unskilled male labourer earned 25s per week in the 1880s.

A Melbourne newsboy, in The Australasian Illustrated Weekly, by Troedel & Co., lithographers, c.1881

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

‘Broomies’ on Swanston Street, by unknown photographer, c.1880

Reproduced courtesy Museum Victoria

On almost every farm the children were made to rise early in the morning and go out to help in the milking sheds or feed the animals before going off to school.

The girls seemed to be chained to the kitchen and were even expected to give a hand with the outside work, during busy seasons.

After the boys leave school, they are expected to work full-time on their father’s property, and for this they receive a paltry few shillings pocket money.

The farmer does not ask his son what he would like to do after he finishes school; he just takes it for granted that the boy will leave school at 14 and come on to the farm.

He seems to regard the children as cheap labor, and once his son can work full time on the property, one of the hands is put off.

The farmer should remember that he chose to be the man on the land, but his son may have other ambitions.

Often a boy, thin of build, and studious, is most unsuited to farm work, and cannot stand up to the strenuous tasks he is allotted.

-Weekly Times, 18 February 1953

In many cases farm children are to be pitied. They have no real childhood. The boys are sent to the cowyards barefooted and the girls are made to work in the house.

-Weekly Times, 30 January 1952

… the laborious work imposed on children of school age by many parents engaged in dairying have arrested public attention… the testimony of many teachers is most emphatic on this point. They state that in certain schools many of the children, on arriving in the morning, are more fit to be put to bed than to be given instruction. They are physically fatigued from the arduous work they have performed, and are obviously suffering from insufficient mental rest.

-The Australasian, 25 May 1907

The ‘family farm’, the keystone of rural settlement in Australia, exacted a toll from the children of farming families. Farming in the nineteenth and early twentieth century, with little mechanisation, was labour-intensive. All family members were expected to contribute, even children as young as eight.

Children undertook a range of farm tasks, including taking care of the animals, planting and harvesting crops. Young boys usually worked in the fields and tended the larger animals, while young girls performed lighter tasks such as milking cows and feeding the chickens. Girls were also expected to do domestic work.

The nature of work went with the season. In the winter children would sort potatoes or clear stones. In the spring they would pull grass, hoe, or plant potatoes. Summer work involved clearing fields and helping with the harvest. Other jobs included cleaning the stables and milk yards, collecting water from wells, and getting in wood for the house. Younger children were given simpler tasks, such as scaring birds away from newly-planted crops.

A young boy cleans the yard at the dairy, near Colac, Victoria, 1935

Reproduced courtesy Museums Victoria

Children were taught when only young to follow the plough, drive the wagon, or to tend sheep. The sons (probably not the daughters) of early pastoralists often minded sheep, spending nights in the bush alone or with siblings when young by modern standards. Poet, Banjo Patterson, recalled his shepherding experiences as a young boy. He wrote:

Away up in front of the house, the (unfenced) country stretched for miles and miles. Flat country, with big belts of timber and patches of scrub. Here it was that we had to do our shepherding – old Jerry’s son Jim, aged about twelve… and my juvenile self. Young Jim left nothing to be desired in my eyes, for he could ride, could boil a billy and could track sheep if ever we let them stray out of sight in the timber. But even at the age of twelve he had his troubles. The dingoes were bad and might rush the sheep at any moment; and his father, old Jerry, had promised him a hiding if he let the two mobs get boxed. It was my first experience of responsibility, and I spent the first few days with one eye out for dingoes and the other out for Jerry’s sheep.

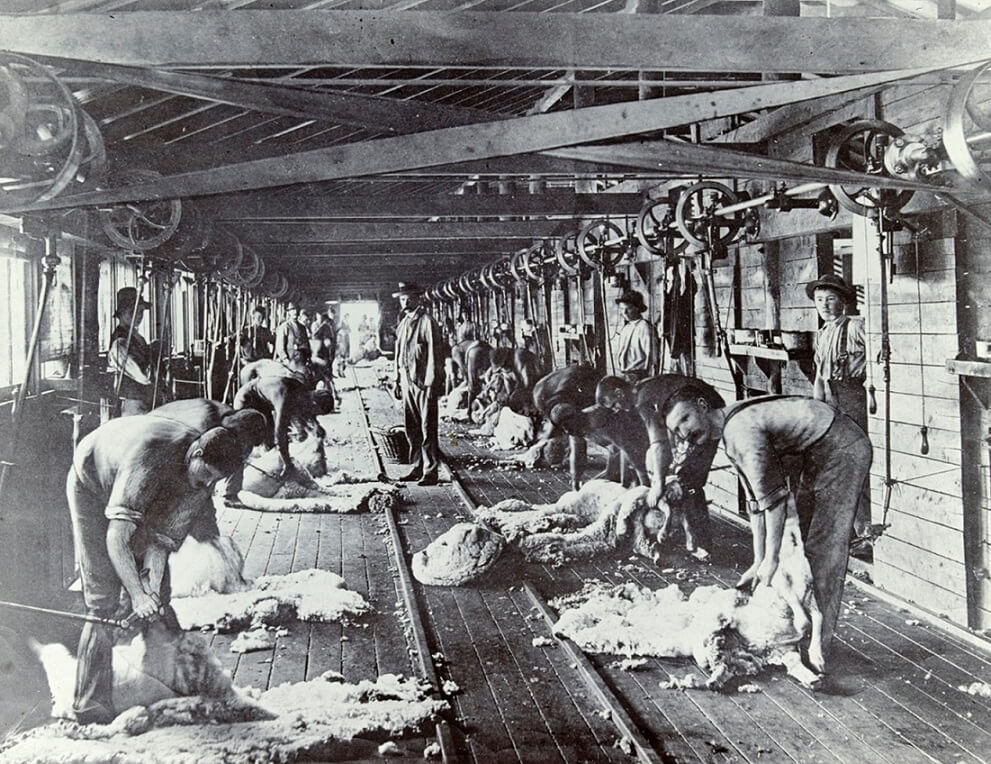

Children were expected to help out during lambing season and were often given the job of ‘lamb tending’. They also worked in the shearing sheds, picking up the shorn fleeces and taking them to the sorting table, sweeping the shed and tarring sheep to stop them bleeding.

Shearers in front of a shearing shed, Australia, c.1900. The workforce includes a number of boys. Two young boys holding browns are ‘sweepers’, keeping the floor clear of fleece.

Reproduced courtesy Museums Victoria

Young boys wait behind the shearers to take the shorn fleece to the sorting table, c,1900

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

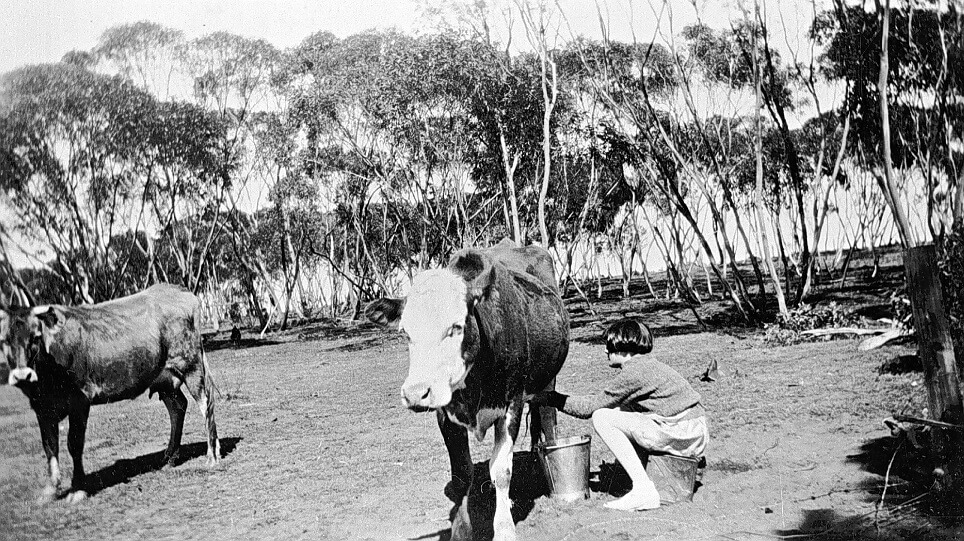

Dairying was an important industry in the colony and milking was an everyday necessity. On almost every dairy farm children were made to rise early in the morning and help in the milking sheds. In 1915 a report by a school inspector in the western district of Victoria was submitted to the Minister of Education. The report found that girls as young as seven were expected to milk cows before school. One girl, aged only 13, woke up at 4:30 and milked 14 cows. She then walked more than 4 kms to school. After school she milked another 10 cows, getting to bed at 10:30pm. The inspector was appalled, reporting:

Children who milk before and after school have been definitely affected wither physically or mentally. The work of examination had not proceeded far when it became apparent that there was an almost universal listlessness running through the school. It was difficult to rouse the pupils: their actions were lifeless. Questioning brought to light the fact that the children, living as they do in a dairying community, are suffering from overwork, chiefly from milking cows in excessive numbers. A statement was obtained from every child engaged in milking as to the hours of rising and of going to bed, the number of cows milked night and morning, and the distance walked to school. The results of the inquiry were astonishing, and showed that the place is a veritable plague spot of child slavery. Some of the children are put to milk cows as soon as they can handle a cow’s teat. The result is that, during school hours, it is difficult to keep children awake, and almost impossible to infuse life into their work.

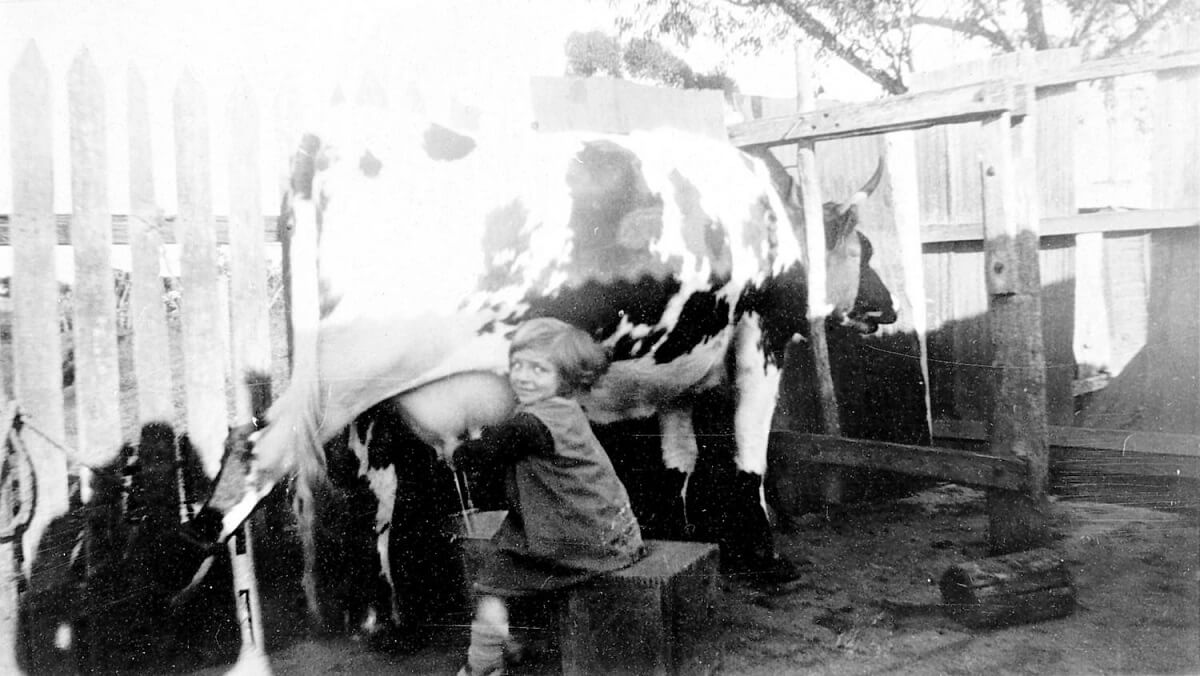

Gladys Schultze milking, c. 1935

Reproduced courtesy Museums Victoria

Gladys can barely reach the ground from the milking stool, but she’s obviously got the milk flowing!

Elma Wright ‘milking’, Victoria, 1937

Reproduced courtesy Museums Victoria

Barely bigger than the tin, Elma knows her way around a cow!

A young girl milking a cow, Manangatang, Victoria, 1936

Reproduced courtesy Museums Victoria

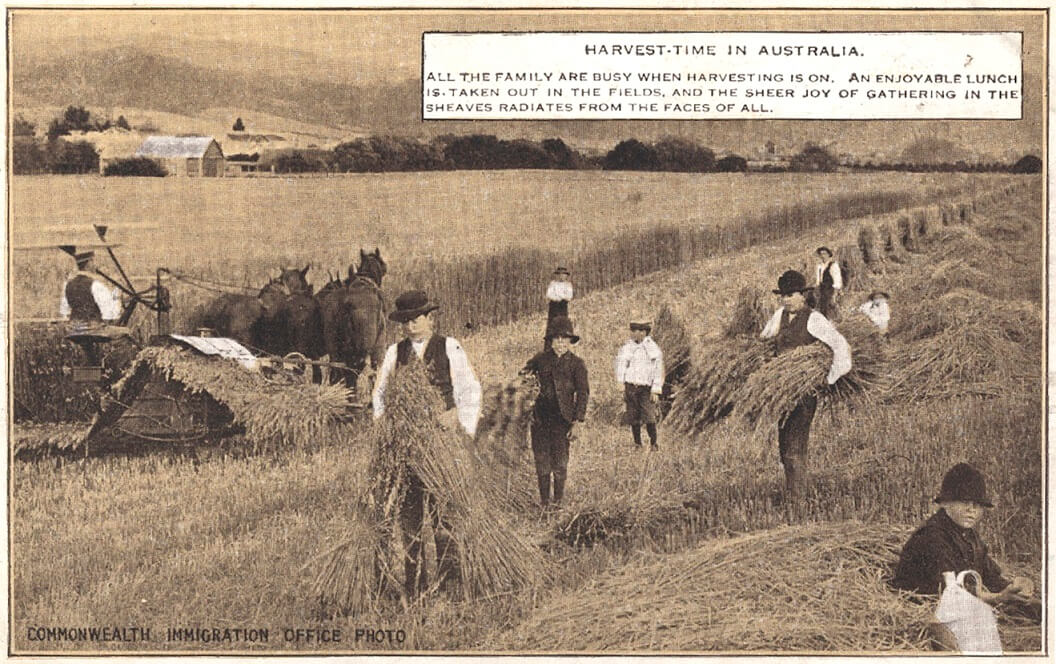

The demands of farm work competed with children’s availability for school. Children were kept home from school to help with a harvest, when it was ‘all hands on deck’! Young family members were particularly good workers — they were both handy and unpaid.

There was no legal way of limiting the hours children worked, or regulating their safety. Along with the long hours of hard labour, many jobs on the farm were dangerous. Children used heavy machinery and sharp tools, were exposed to pesticides, snakes and harmful insects, and worked for long hours in sometimes extreme weather conditions. At times the work proved hazardous, even fatal.

Rules have changed and children on farms can only perform ‘light work’ today. This is work that is not likely to be harmful to a child's health, safety and welfare, and does not affect a child's ability to attend school. That said, while agriculture remains based on the family farm structure, children will continue to do farm work.

Mabel Pendlebury milking, Boosey Victoria, 1935

Reproduced courtesy Museums Victoria

Women on dairy farms with small children often had no option but to take them to the milking shed. Here Mabel Pendlebury is accompanied by her two small sons, who are, literally, underfoot, regardless of the muck and mud of the cow shed.

Milking, Connewirricoo (Wimmera), c. early 1900s

Reproduced courtesy Museums Victoria

One woman and perhaps an older girl are milking while another (younger) girl carries a full milk pail. Older girls often helped with the milking, sometimes taking full charge. This might involve more than an hour in the shed before and after school on a daily basis. A kerosene tin has been used as a milking stool.

Rabbits were introduced to Victoria in about 1860 and soon multiplied, spreading into neighbouring properties and then through Australia at a spectacular rate. By the early 1870s there were major outbreaks in the Mallee and districts around Colac, spreading to Geelong and the Otway Ranges. In dry years they descended on crops with devastating ferocity: one farmer lost all 70 acres of his wheat crop in five days and feared being forced to give up his land! Farmers spent valuable time and energy digging out warrens, trapping and poisoning the rabbits, but they could not clear them from adjacent scrub or grazing land. Soon there were literally millions of the pests.

Men were hired to keep them in check. Some worked full-time as rabbiters, while others added trapping rabbits to a daily or weekly work schedule. Farm children became expert at digging out burrows and setting traps.

A boy with a catch of rabbits, Manangatang, Victoria, c.1935

Reproduced courtesy Museums Victoria

A boy collects his rabbit from the trap. His sled was used to drag wood and kindling back home.

Reproduced courtesy Museums Victoria

A boy rides on a wagon-load of hay, with a second child manning the rake. Photograph taken in the Bairnsdale District, Victoria, c.1915

Reproduced courtesy Museums Victoria

As is still common today farm boys (less often girls) acquired driving skills early in life. The cart would be loaded in the field, and driven to the barn by the children. Accidents occurred frequently, and still do, where children participate in farming activities.

Looking after the chickens was a task often allocated to the youngest children. Photograph by Alice Manfield, photographer, Mt Buffalo, c.1890

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

One of a series of postcards issued by the Commonwealth Immigration Office during the early 1920s, promoting immigration to Australia for rural settlement. The postcard suggests a somewhat idyllic scene with a family engaged in the task of gathering in the harvest.. Children and other family members collect the sheaves of bound hay dropped by the binder and stack them in stooks to dry in the sun before threshing.

Reproduced courtesy Museums Victoria

In the home

With large families and few labour-saving devices in the home, girls were expected to help. They cleaned the house, sewed, washed, ironed and mended the clothes and helped to cook the meals. Young girls usually learned to cook from their mothers, beginning with simple dishes when quite young. For poor women, widows and deserted wives, taking in washing and ironing was an option well into the twentieth century. The children of washerwomen often helped, collecting dirty washing or returning the clean, ironed parcel.

Children began work as domestic servants at an early age. Girls as young as ten or eleven might find work as ‘mothers’ helps’, nursery or skullery maids, progressing to general servants or more specialised work. Boys often began as stable boys or gardeners’ assistants. With the advent of compulsory schooling children started work later, but many expected to be in the workforce from the time they turned 14 or 15.

Domestic service was poorly paid and frequently required women to live in, on call at all hours. A servant’s day could begin before six in the morning (or five am on wash days) and not end until after six or seven at night. There were many reports of servants being required to sleep on kitchen floors or on verandahs with little privacy or comfort.

Life as a domestic servant held additional risks. Sexual molestation by the master, older sons of the household, or other servants, occurred. It was a particular problem where female servants were not allotted bedrooms with lockable doors. Unwanted pregnancies were common amongst domestic servants, and the fate of such women was unjust: many were promptly dismissed, often without a ‘character’ (reference), leaving them facing immediate destitution. Their sexual partners, or seducers, were rarely named or held accountable. Faced with certain disgrace, some women sought an abortionist, working in the shadows of Melbourne’s society. Others gave birth to their babies and surrendered them for adoption. In some tragic cases the babies were either abandoned, sent to the ‘care’ of a ‘baby farmer,’ or even killed by their mothers in desperation. It was almost impossible for a woman to support herself while caring for an infant or small child, as most jobs in service required the woman to live in.

Madam Strachan and her three maids, Creswick, Victoria, c. 1890

Reproduced courtesy Museum Victoria

Each of the (rather young looking) maids holds an item, probably representing different tools of trade. The servant at top left holds a scrubbing brush.

The Biesh family and their two maids, Quambatook, Victoria, c.1909.

Reproduced courtesy Museums Victoria

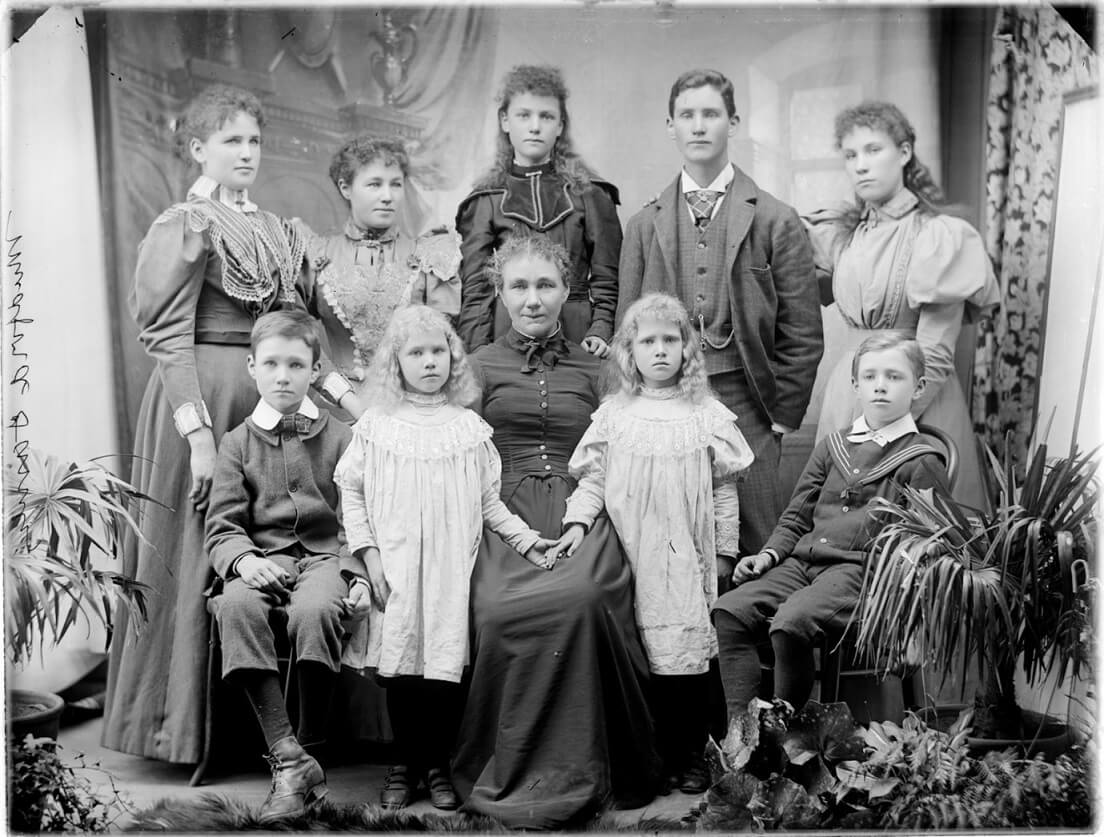

The Mudford family, Kyneton, 1890s

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

Families of this size were quite common in the 1890s. Mrs Mudford was pictured with nine children, including twin girls. Caring for a family of this size was hard work and girls were expected to help in the house. Boys were given outside jobs.

Authors: Ann Wilcox and Margaret Anderson

Sources / Additional Reading

Online sources / institutions

State Library Victoria

Museums Victoria

Trove, National Library of Australia

Public Record Office Victoria

Victorian Parliamentary Library

Secondary Sources

Andrew J. May, Melbourne Street Life, North Melbourne, Australian Scholarly Publishing Pty Ltd, 1998

Exhibition catalogue, ‘Melbourne's Newsboys’, City Gallery, Melbourne, 3 May to 24 July 2005

Johnston, ‘The Role and Regulation of Child Factory Labour During the Industrial Revolution in Australia, 1873-1885’, International Review of Social History, 65(3), pp. 433-463

Maree Murray, ‘Children’s work in rural New South Wales in the 1870s’, Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society, 79(3-4), pp. 226-244

Simon Sleight, Young People and the Shaping of Public Space in Melbourne 1870-1914, Surry England, Ashgate Publishing Limited, 2013