Both the number and the scale of factories increased in the later decades of the nineteenth century, assisted after 1866 by protective tariffs on imports. The tariffs were introduced to help local industry compete against imported goods and were applied initially to imports from both overseas and other colonies, notably New South Wales. In the aftermath of gold, Victoria needed both employment options for former diggers and another source of revenue. Tariffs promised both. Tariff protection was a controversial issue, but the protection cause was championed by some influential advocates, including David Syme of The Age. When the Legislative Council rejected a tariff protection bill in March 1866, his editorial was scathing.

The Legislative Council has done well to accept the responsibility of the situation. In rejecting the tariff, hon. members have at least escaped the charge of cowardice. They have shown, however, that there is no limit to the recklessness of their obstruction; that they are utterly regardless of the public welfare, and are prepared to welcome confusion and strife rather than abandon their stupidity and obstinacy. They have dared the country to the conflict; and, if the country shrinks now, it must henceforth be content to be the Council's very humble and obedient servant. There are difficulties of no ordinary magnitude to be encountered; but there is no occasion for fear. The people know the value of their rights too well to hesitate to defend them, even at the risk of temporary trials and embarrassments. If they and their representatives in the Assembly be but true to themselves at this juncture, there can be no apprehension of the result. The rejection of the tariff by the Council is the first step to the attainment of victory by the people, for it will effectually settle the arrogant pretensions of that House, whose members would inflict upon the colony the domination of an aristocracy of the very worst character — for it is based on wealth alone, and that, in many instances, acquired — an aristocracy without intelligence, without education, without birth, without refinement, without social influence ; destitute of everything that could win for it the slightest mark of respect. (Age, 14 March 1866, p.4)

Later in the century, the free trade vs protection debate was a source of significant intercolonial friction, that continued into the period leading up to Federation.

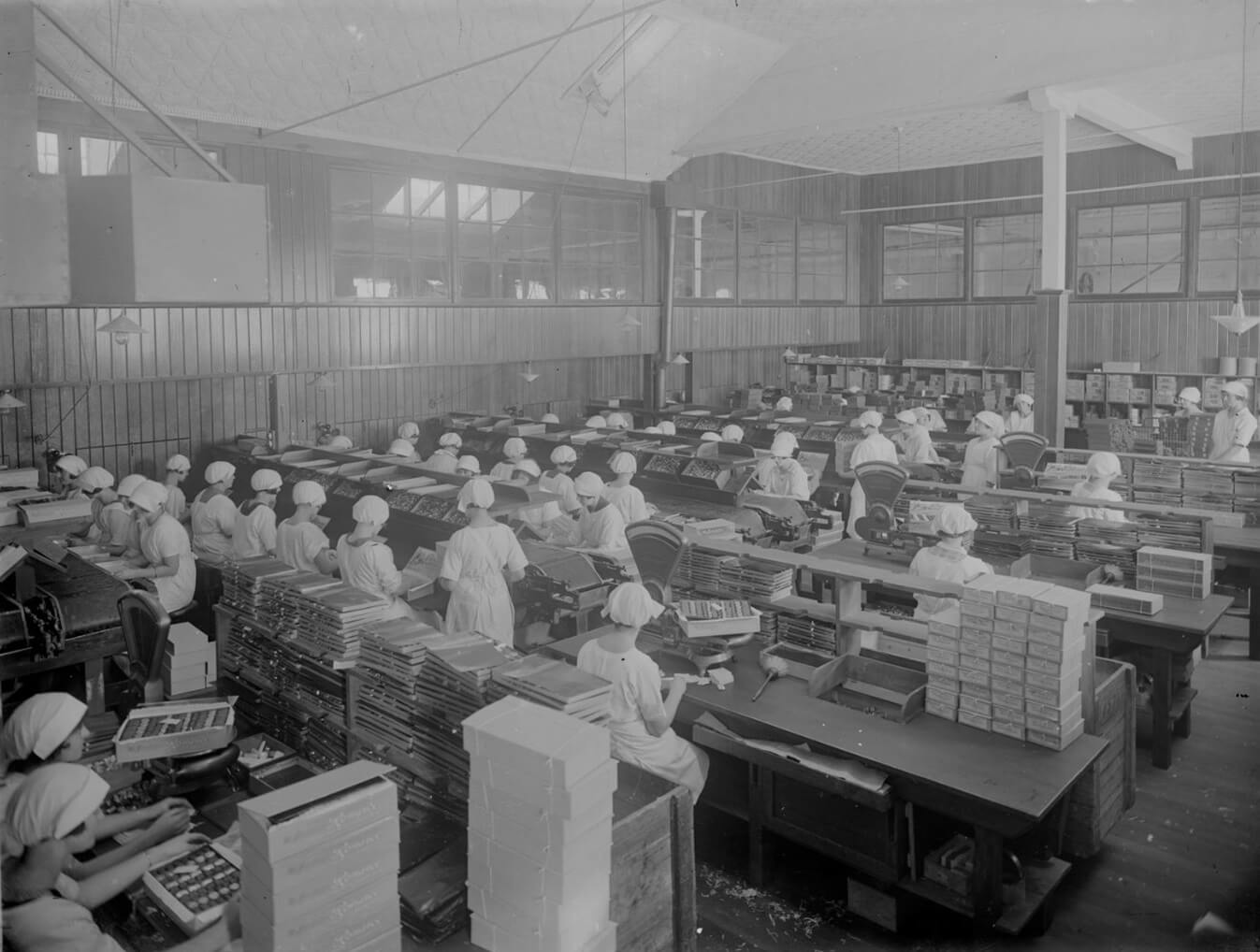

However the protection provided by tariffs allowed Victorian industries to expand in both number and scale. By 1891 there were over 3,000 factories employing some 52,000 workers: by 1902 this had grown to 4,000 workshops, employing 73,000 people. While most of these were still small concerns, the number of factories with more than 200 employees grew steadily. By 1891 there were 31 factories of this scale in the colony, including some huge companies that sprawled over large sites in Fitzroy, Collingwood and regional Victoria. They included famous works like the MacRobertson Chocolate factory that spread ultimately over more than 30 acres in North Fitzroy. It was known as the Great White City, since its buildings were all painted white, and the workers also wore white uniforms. At its peak the factory employed several thousand workers, many of them women and girls.

Packaging chocolates MacRobertson Chocolate Factory, c. 1920s

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

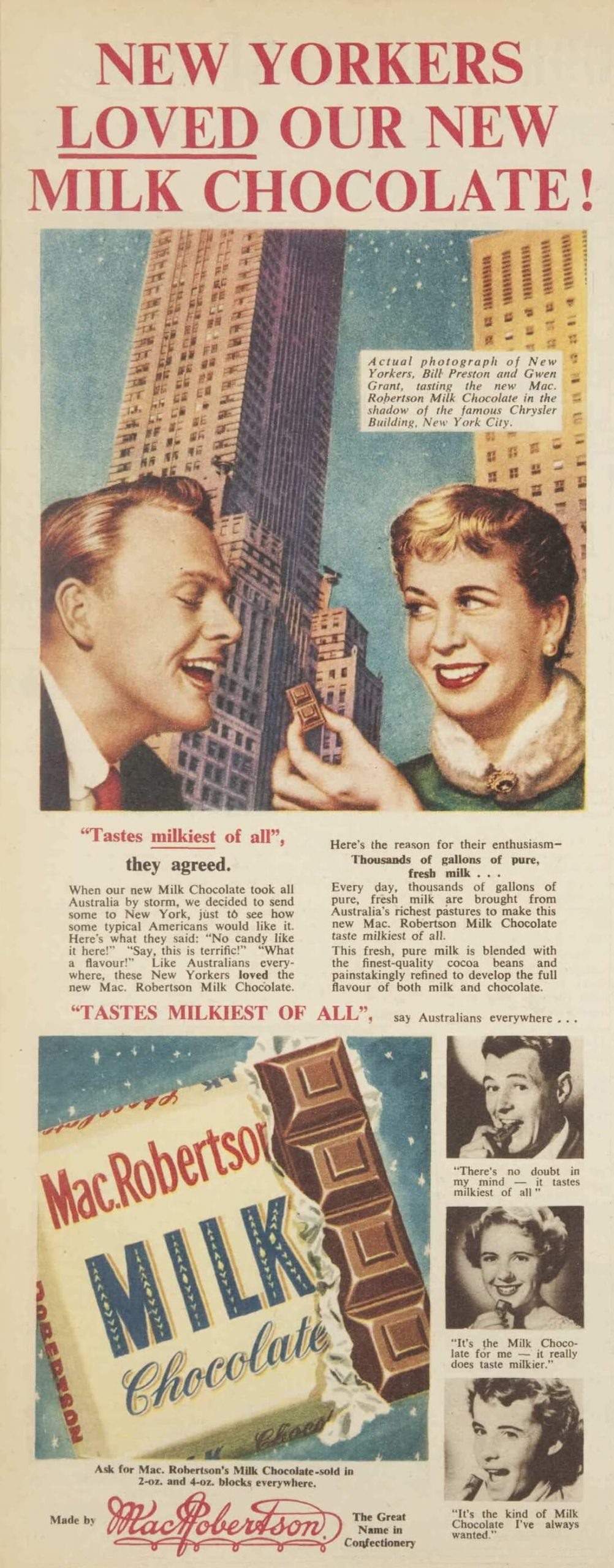

By the early twentieth century MacRobertson was the largest chocolate manufacturer in Australasia. Amongst its huge range were favourites like Old Gold chocolates, Freddo Frogs and Cherry Ripe bars, still popular today. MacRobertson was a veritable rags to riches story. Founder of the firm, MacPherson Robertson, famously began his business in 1880, making confectionery in a makeshift boiler in the family home in Fitzroy and selling from a tray he carried through surrounding suburbs. Success encouraged him to form the MacRobertson Steam Confectionery Works, which by 1896 had grown to occupy more than three acres of land in Fitzroy, in a complex employing 260 workers. From the beginning, the buildings were painted white. MacRobertson understood both the manufacturing process and the importance of marketing his products. He advertised extensively and eventually his business grew to export chocolate to an international market. MacRobertson worked in relative harmony with his employees, supporting the creation of the Female Confectioners’ Union and maintaining a ‘closed shop’ employment policy (employing only union members). He refused to join other confectionery manufacturers in blacklisting union ‘troublemakers’. From 1900-1922 he sat on the confectioners’ wages board.

Advertisement for MacRobertson Milk Chocolate, Australian Women’s Weekly, 1 September 1954

Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia

Advertisement for MacRobertson Old Gold Chocolates, Australian Women’s Weekly, 8 May 1948.

Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia

Industry in the regions

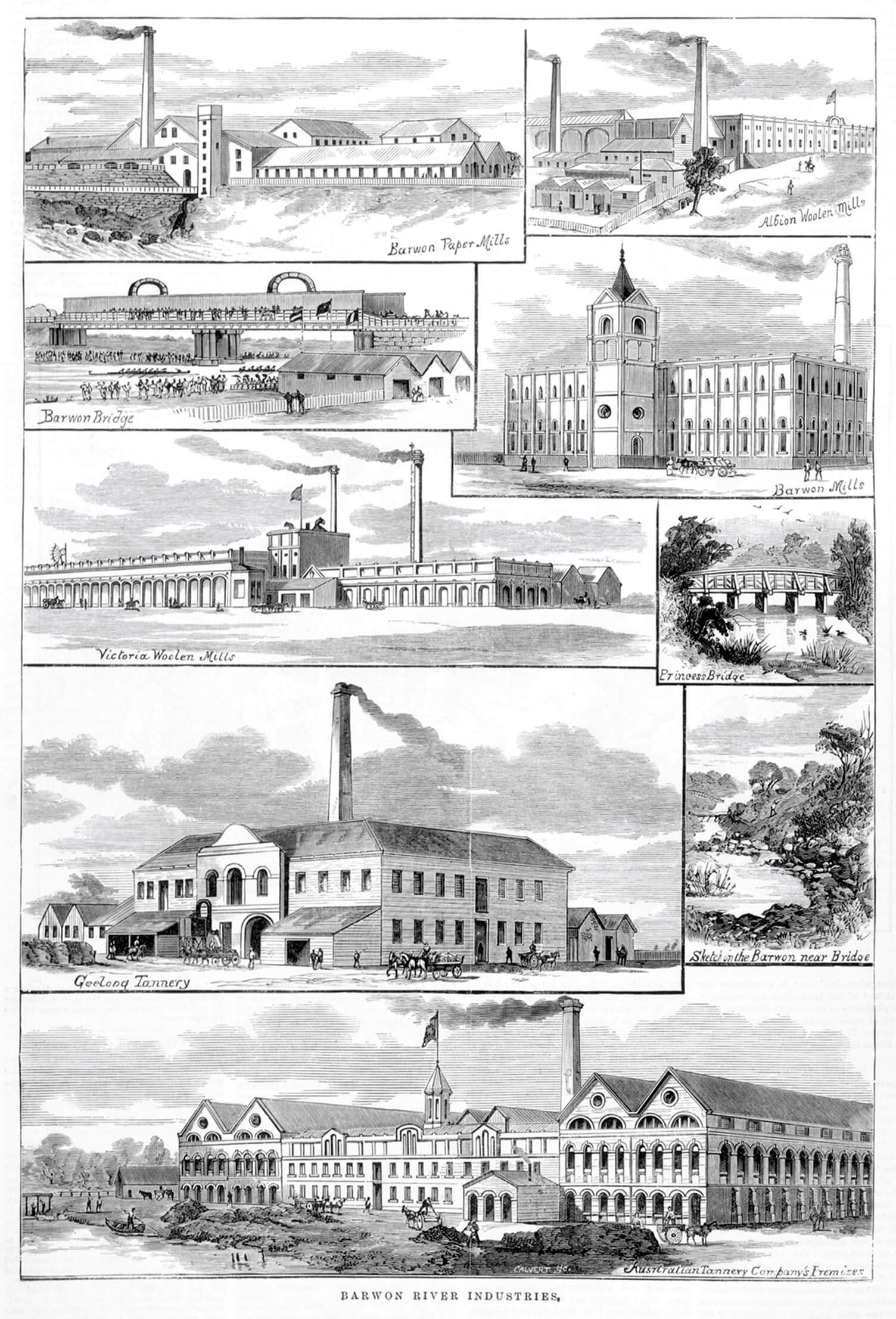

The scale of industry also expanded in regional Victoria. By the end of the nineteenth century Geelong was an important industrial centre, with many factories located along the Barwon River. They included tanneries, several woollen mills and a paper mill, all providing work for locals.

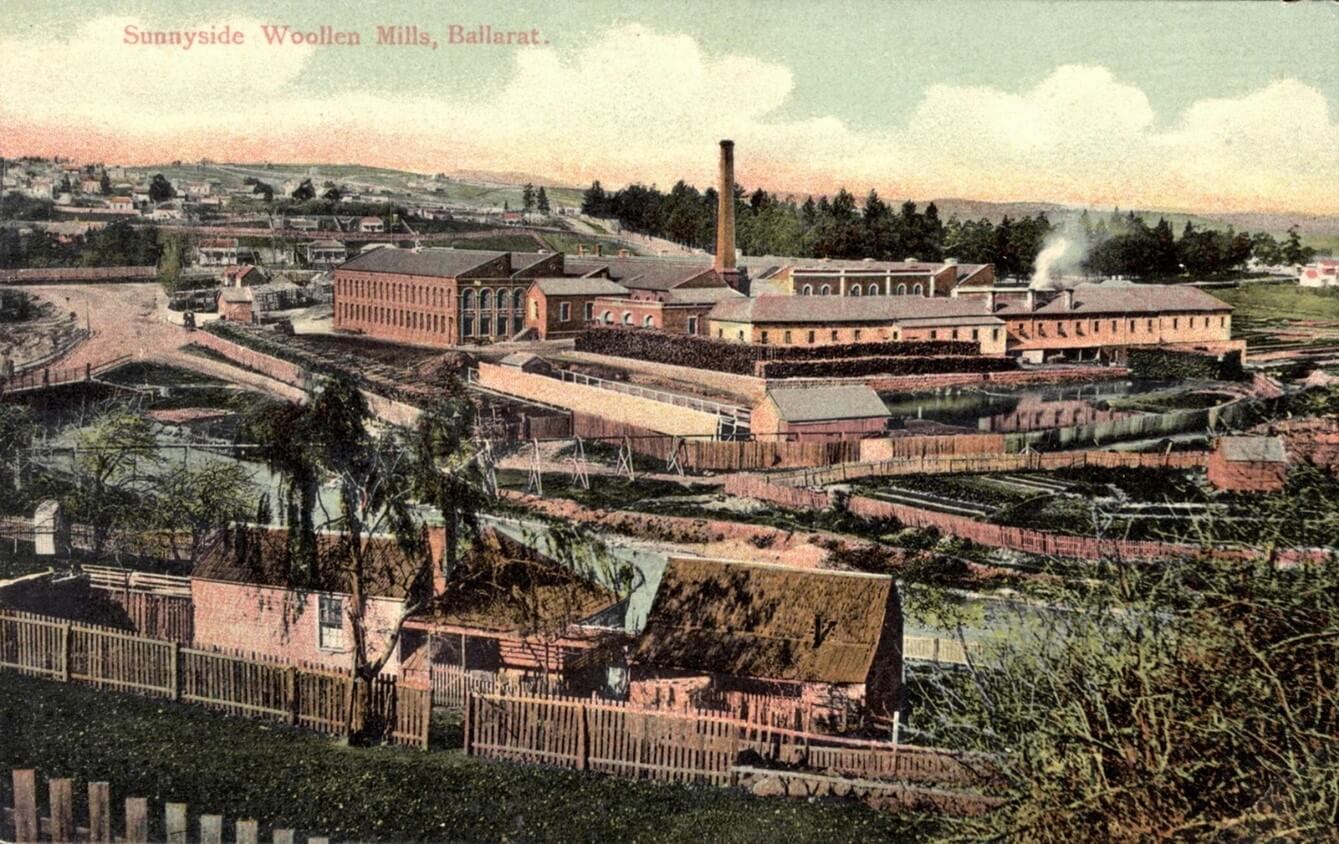

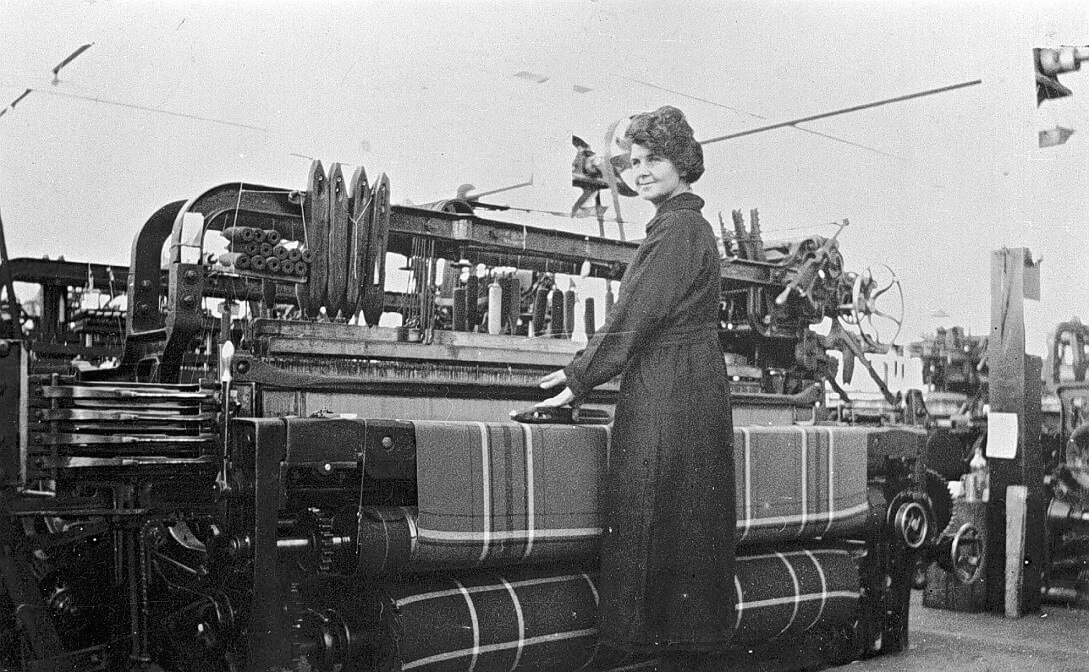

Woollen mills were an important feature of the industrial landscape in many other regional towns. Ballarat, Bendigo, Castlemaine, Wangaratta, Warrnambool and Corio all had woollen mills, some of them very substantial factories employing many local workers. Mills were sometimes built in smaller towns, like Clunes, too although they did not always last. A shortage of available labour was often a challenge and increasingly the mills were concentrated in larger towns and in the city. These textile mills employed large numbers of women and girls. The expansion of the railway network in Victoria was an important factor in the successful development of industry in regional Victoria.

Sunnyside Woollen Mills, Ballarat, c. 1907. Postcard

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

The Woollen Mills, Castlemaine, no date but possibly c.1920s

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

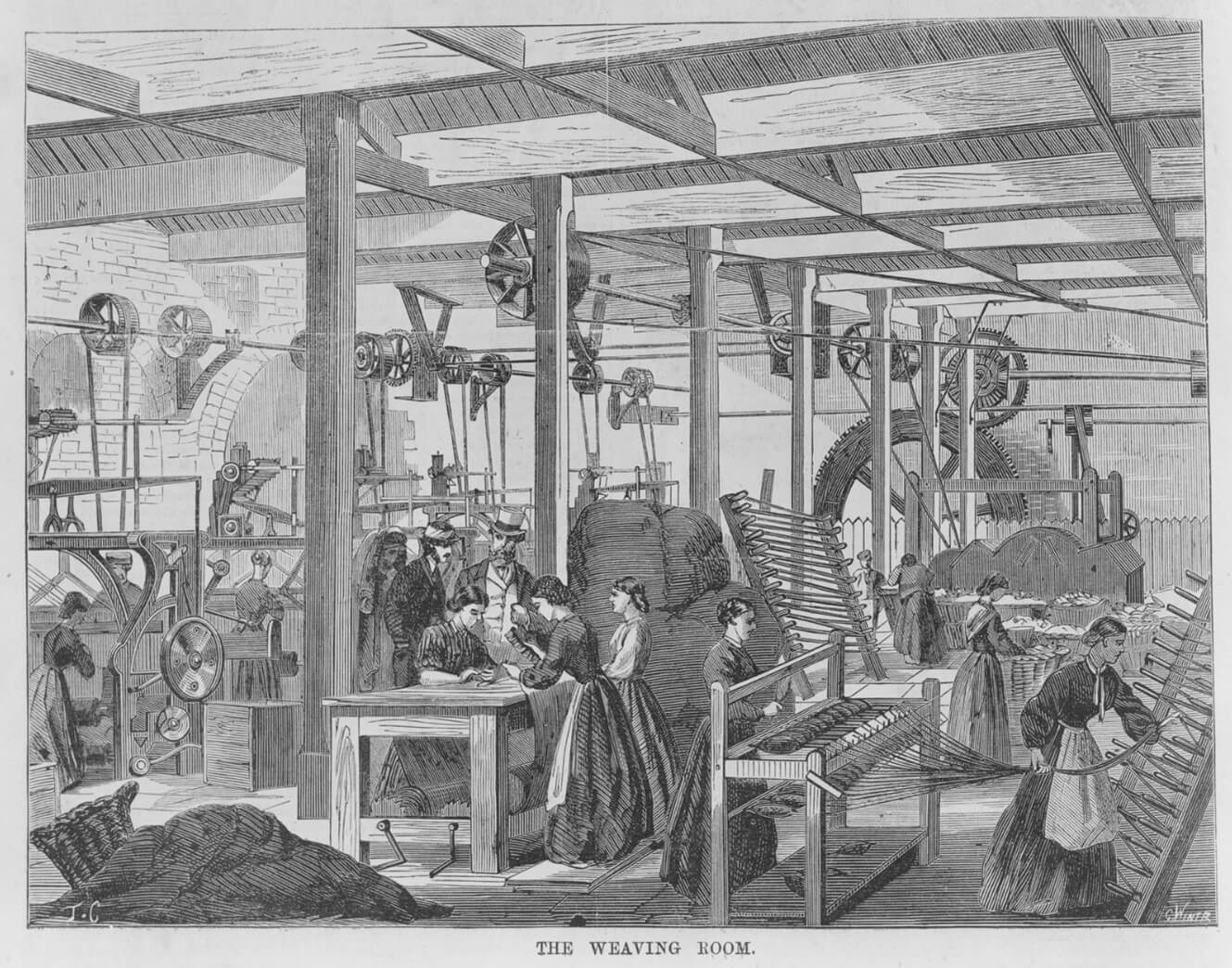

From the beginning, textile mills employed both men and women. As the engraving from the 1860s shown here shows, early factories had little in the way of safety equipment in place and women’s clothing of the time must have been a major hazard. There were many accidents involving workers caught in moving machinery, and that is not surprising, looking at this picture.

The Weaving Room, Melbourne factory, 1868

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

Published in the Illustrated Melbourne Post, 20 June 1868

Woman operating a weaving loom, Myer’s Mill Ballarat, c. 1925

Reproduced courtesy Museums Victoria