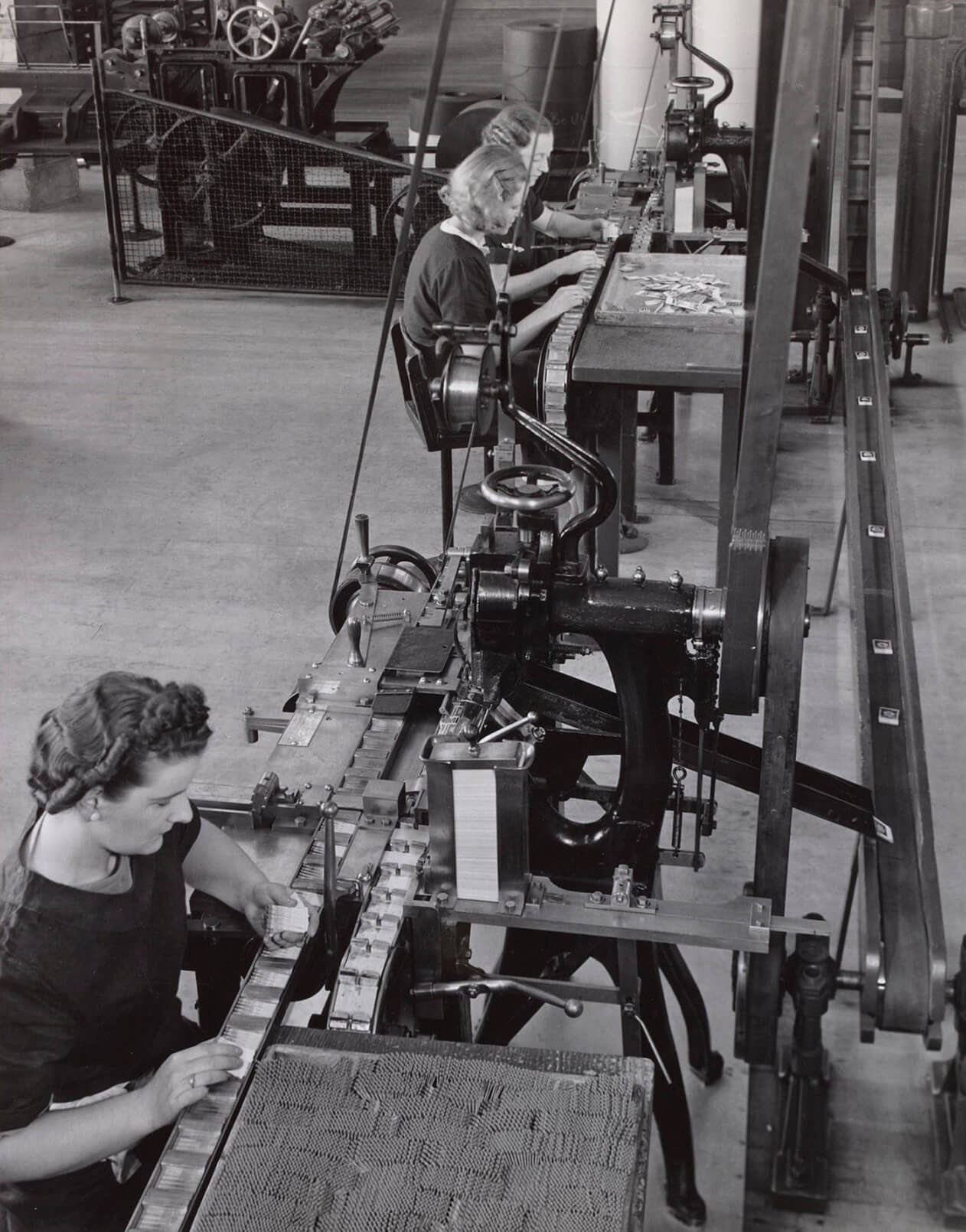

Although factories continued to be important employers in regional Victoria, Melbourne became increasingly dominant in the twentieth century. By 1913 two thirds of all factories were located in the city. The largest concentration was in clothing and textiles, followed by food and drink processing. About one third of these shops were small concerns, employing between five and ten workers. The 1920s and thirties saw further expansion, and the development of new industries in distilling, mineral oil production, the manufacture of domestic stoves, hosiery and knitting mills. Increasing numbers of women were recruited to work in these factories.

Umbrella making, Melbourne, 1934

Reproduced courtesy Public Record Office Victoria

Manufacturing nylon stockings, Melbourne, no date but possibly c.1950s

Reproduced courtesy Public Record Office Victoria

Industry shapes the city

Clusters of industry already shaped the city in the nineteenth century, and this continued after 1900. Many areas became known for the industries in their locations. Flinders Lane was associated for many decades with the clothing industry, known colloquially as the ‘rag trade’. The street was once lined with workshops, from high-end fashion houses to those producing cheap, ready-to-wear clothing. Amongst the fashion houses were several owned by Jewish immigrant families. Most employees in the rag trade were women, although usually supervised by men. The rag trade dominated the street until the 1960s, when problems with space and car parking proved insuperable.

Secondary industry also dominated most of the inner suburbs of Melbourne. North Melbourne, Carlton, Fitzroy, Collingwood, Richmond, South Melbourne, Port Melbourne and Footscray were all dominated by factories until the 1960s, and the suburbs became known as working class areas. Some factories were huge concerns, like ‘Gibsonia’, a complex of textile mills in Collingwood, owned by the department store Foy and Gibson. The boot, shoe and clothing trade dominated nineteenth-century Richmond, joined by match factories, processed foods and heavy engineering in the early twentieth century. The giant Bryant & May match works employed hundreds of workers in their Richmond factories, including many women. Their factories claimed to be model workshops, with sporting facilities and a cafeteria for workers.

Foy & Gibson factory, Smith Street Collingwood, c. 1906

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

Bryant & May employees in front of the Richmond factory, 1926

Algernon Dargy photographer

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

The British firm bought premises in Richmond in 1909 and continued manufacturing until 1987. Their famous ‘Red head’ matches were made there from 1946.

Women workers assembling match boxes, Bryant & May factory, c. 1939

Wolfgang Sievers photographer

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

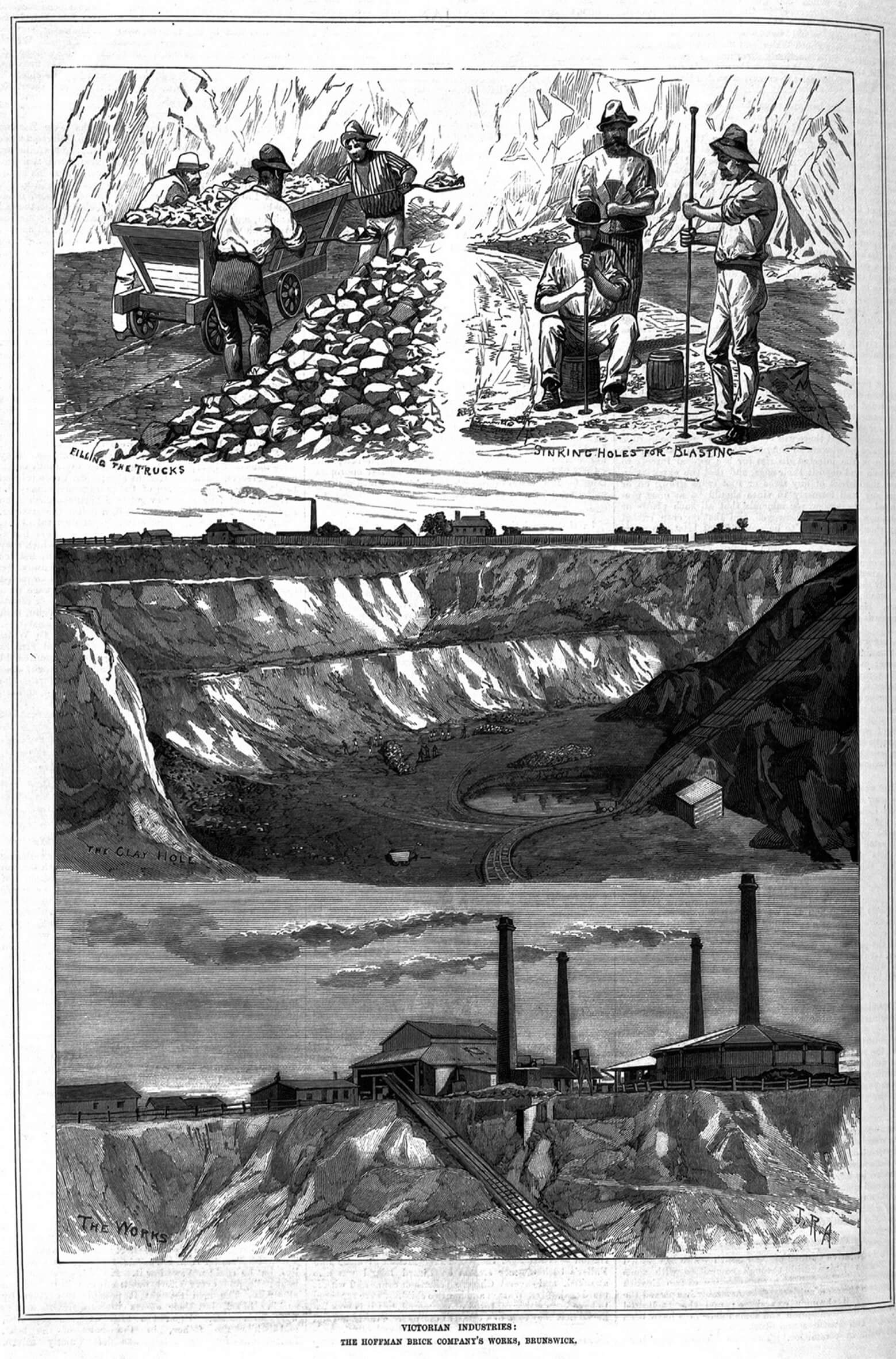

To the north of Melbourne the suburb of Brunswick was dominated by stone quarries, brick works and potteries, the latter working large deposits of local clay. Works and houses spread around the main north road to Sydney from the 1840s, and the high street is still called Sydney Road to this day. Clusters of small workers’ cottages grew up around the brick works, which expanded as the demand for housing increased after the gold rush. Although the brick industry suffered particularly badly during the depression of the 1890s, it recovered to continue operating in Brunswick until the 1990s. Elements of the original kilns can still be seen, now incorporated into inner-city housing developments. One of the early clay pits is now a park, after a long period of less salubrious use as a rubbish tip.

The Hoffman Brick Company’s Works, Brunswick, 1881

Wood engraving. Julian Rossi Ashton artist

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

Published in the Australasian Sketcher, 19 November 1881.

Along with South Melbourne, Brunswick was also known for its rope works. Some limited rope making remains in the area, but former manufacturing methods are also reflected in the laneways and street names of the suburb. Rope Walk reflects the period when rope makers spread their hemp along the laneways, then literally walked the length of the rope, twisting the strands to make the rope as they went.