During the 1960s youth rose to wield enormous cultural and economic power and youthfulness itself became a fashionable ideal and commodity. In this article I argue that the demise of Australia’s clothing manufacturing industry is directly linked to the ‘younging’ of both society and culture. The societal refocus towards youthfulness, combined with the whimsy of youth consumers from the 1960s, contributed to the segmentation of the fashion market and the subsequent fragmentation of local textile, clothing and footwear (TCF) manufacture. This, in concert with ongoing structural problems within the industry, destabilised Australia’s industry foundations, making it difficult for it to withstand the pressures of globalisation that manifested from the 1970s.

The Youthquake

In its 1 January 1965 New York edition Vogue announced the arrival of what it called the ‘youthquake,’ putting a name to a phenomenon that had already swept England and France. Vogue’s editor Diana Vreeland coined the term to describe the power and influence of youth in bringing about social and cultural change. By 1965, this power was evident in the United States (US) in numbers alone. The US population of approximately 190 million comprised about 90 million from the baby boom generation under the age of 24. Vreeland’s editorial spoke to the teenagers in that demographic, describing 13 as “the new jump-off age” and exhorting these youngsters to realise their daydreams immediately rather than waiting to grow up. She wrote, “Gone is the once-upon-a-daydream world … you can already be what you want to be.” In the US in 1965, the youthquake had already transformed teenage daydreams into reality for the young models and television personalities featured in the pages that followed Vreeland’s editorial in that edition of Vogue.

However, on Australian shores, ‘teenager’ was a term that people were still coming to terms with. The separate life stage between childhood and becoming an adult had gained little recognition here and the baby boom generation was only beginning to telegraph its social and economic might. The first major display of mainstream teenage power to be witnessed here were scenes of ecstatic teenagers welcoming the Australian tour of pop idols The Beatles in June 1964. Up to this point, the ripple effect of the youthquake sweeping the northern hemisphere had been given little attention. And ready-to-wear fashion markets were a visible reflection of this inattention.

Fashion in Australian stores aimed at teenage girls was still modelled on similar styles to those worn by their mothers and older women. Even the Australian Women’s Weekly teen-focussed lift-out, Teenagers Weekly, showed styles that were just smaller versions of the adult fashion appearing on the main pages of the magazine. Mainstream Australian fashion clung steadfastly to its traditional influences — the wealthy elite, royalty, and the dictates of Parisian couture, largely ignoring what was happening on the fashion fringe. As a result, the similarity of fashion offerings across the age groups made it difficult to differentiate the young from the more mature women. Home sewing was one way for creative youngsters to get the latest looks seen in overseas fashion magazines and thereby individualise their appearance. But for those who lacked the skills to design and/or sew their own clothes, the ready-to-wear market of the early 1960s held great disappointment.

On 18 May 1964 the Sydney Morning Herald’s feature lift-out Textiles: A Survey of the Australian Cotton and Man-made Fibre Industries published the industry views of many of the doyens of Australian textiles. One industry pillar and founding director of hosiery, lingerie and textile manufacturer Prestige Limited, George Foletta said “the world is younging – youth is taking over and new developing economies will call the tune.” Foletta’s prediction of the world’s younging preceded Vogue’s declaration of the youthquake, as well as the hype around the arrival of The Beatles, and in conservative Australia of the day, it might have seemed fanciful. But on 30 October 1965 it came to pass in spectacular fashion when Swinging London and the youthquake were dramatically drawn into the Australian spotlight as 22-year-old English photographic model Jean Shrimpton, sponsored by American chemical giant Du Pont de Nemours Inc, strode onto the lawns of Flemington Racecourse on Derby Day. Australian reactions to Jean and her comportment ranged from outrage to ambivalence depending upon one’s societal position, age or gender. The staid and traditional social mores of 1960s Australia, and the perception of the country as a fashion backwater, suddenly became newsworthy on the international stage. At home, Jean’s double fashion faux pas polarised Australia’s older generation: the simple shift dress that revealed four inches of bared flesh above her knees scandalised some; with others mortified by potentially the greater of the sins — appearing in the sacrosanct Members Enclosure at Flemington minus the obligatory hat, gloves and stockings. “If Miss Shrimpton wants to wear skirts four inches above the knees in London, that’s her business. But it’s not done here,” said Lady Nathan, the indignant former Lady Mayoress of Melbourne, quoted in Melbourne’s Sun on 3 November 1965. Commenting further, Lady Nathan referenced Jean’s flouting of the dress codes by calling her a “bad-mannered child.” Notwithstanding the ire of those in the Flemington Members Enclosure, Jean’s freshness, simplicity of style and apparent disregard for the strictures of convention inspired many young women, while young men simply appreciated the spectacle.

This moment in time has since been celebrated as a defining moment in Australia’s cultural history — the spark that ignited mainstream youth fashion culture here. By 1965 Australia, like its northern hemisphere neighbours, also had a substantial population in the 15-24 age bracket. And as it was a time of full employment, most Australian youth were in the workforce with their own disposable incomes. Forward-thinking entrepreneurs such as George Foletta had predicted the economic advantage of catering to the young, and retailers such as David Bardas, the managing director of Sportsgirl, astutely recognised the spending power of this group. Copies of Shrimpton’s miniskirt appeared in Sportsgirl’s windows within days of Melbourne Cup that year.

Consumers of fashion

After the Shrimpton episode, the styles of Swinging London and other fashion hothouses of the northern hemisphere quickly migrated onto mainstream youth’s radar. Fashion became a visible way for young people to distinguish themselves from the older generation and from each other. As the decade unfolded, the tsunami of social change that followed the youthquake gathered momentum and the young with cash to splash clamoured for more fashion choice in the ready-to-wear market. They sought affordable fashion that was easy-care and up-to-the-minute in styling to match their lifestyles. Their weekly pay packets enabled greater freedoms than those experienced by their parents’ generation during the war years and for most, leisure, having fun and individualising their appearance became the pastimes of youth and consumed the greater proportions of those pay packets.

To be “new, exciting and different” was Sportsgirl’s slogan, but it also neatly captured the spirit of the era and what separated young Australians from their elders. Evanescence influenced lifestyle and the outlook of this generation as well as the speed of consumption of clothing. Quality was not the primary concern and retailers sought to oblige with cheap garments designed for fast turnover. Shopping itself became a pastime and the insatiable quest for novelty pressured local clothing production of ready-to-wear fashion. The youth-led segmentation of the fashion market forced changes to garment production.

Segmentation of Fashion Production

The two-season or six-monthly cycle of range delivery was the Australian model whereby summer ranges appeared at the end of winter and winter ranges were in the shops in February. It had been the traditional way of operating and it meant that manufacturers could forward plan, allowing time to devise or copy last season’s northern hemisphere ranges, order textiles, plan production schedules and thereby, achieve some advantages from economies of scale. But this cycle became insufficient to satisfy the transitory nature of youth fashion whimsy. Speedy fashion turnover in stores enticed customers to return with frequency. Greater frequency was needed to sustain impetus in a changing marketplace and to separate the young from their money. Before eventually implementing a vertical business structure model that eliminated the middlemen in the supply chain and saw garments made in-house exclusively for retailers, Sportsgirl experimented with rapid response ranges on a weekly cycle. Styles were? introduced on Mondays with more of the better sellers reproduced by small maker-uppers in and around the CBD for restocking later in the week.

Working at a lightning pace in nearby Flinders Lane, young designers such as Prue Acton supplemented this fast turnaround of department store stock. This rapid response method of retailing conditioned the consumer to want smaller (and seemingly more exclusive) quantities of multiple new coordinating styles delivered at turbo-charged speed. Not only was the market segmenting between mature and young styles, the speed of fashion obsolescence and the uptake of coordinates meant that the market was subdividing even further, intensifying the pressure on the large manufacturers. To satisfy an increasingly-segmenting market, small runs of garments and other ‘cool gear’ produced without economies of scale, often superseded what had been profitably manufactured in fewer but larger runs. According to trailblazing British designer Mary Quant in her 2012 autobiography, you needed to be “right for the times – a little ahead of the times but not too much.” However, for volume manufacturers with their large workforces, putting such advice into practice was fraught with risk. As a result, many manufacturers continued with what they knew best and many chose to ignore the youth fashion scene.

Other volume manufacturers, such as Maurice C Dowd Pty Ltd whose records have been made personally available to me, navigated the changing times by maintaining core production of a staple product while diversifying into fashion production under contracts to cut, make and trim for other designers and manufacturers. Dowds was a medium to large-sized operation and throughout the 1950s and 1960s relied on contracts to produce Hickory foundation garments under licence. The company’s experience in the precision manufacture of bras well-positioned them to branch out into swimwear manufacture for Australian designers such as Kenneth Pirie and Paula Stafford. Additionally, they tested the waters in fashion outerwear for the Australian domestic market under licence from American teenage label Bobbie Brooks. After discontinuing production of Hickory from the early 1970s, Dowds continued to embrace the ‘younging’ of the market with the launch of its own fashion outerwear label, The Clothing Company. Staples such as Jag Jeans for Adele and Rob Palmer and volume fashion for labels such as Country Road and Esprit, became core products in the wake of Hickory over the next few decades. While market forces changed the type of garment offerings produced by local manufacturers, state and local government decentralisation programs throughout the period, also lured manufacturers to consider a geographic change of location for their operations.

Clothing manufacturing and decentralisation

Since the 1940s, the geographic spread of the industry itself had been changing as decentralisation became the buzz word of the postwar recovery. Chronic labour supply issues had prevailed industry-wide throughout and since the postwar period, despite Australia’s robust immigration program. With the promise of an untapped labour supply in country towns, manufacturers had been financially incentivised through state and local government programs to set up new factories, or to relocate existing facilities, into regional areas. The rationale was to provide jobs to boost country towns and to stop the drift of the young to the cities. Cash assistance, cheap loans and leases on council-owned buildings, subsidised transport and telecommunications, and payroll tax rebates were some of the advantages of relocation to the regions. And these financial benefits had a similar effect to autumn rains on dry paddocks — clothing factories sprang up like mushrooms across the state from Warragul to Warrnambool, Wonthaggi to Wangaratta, and Morwell to Mildura.

Decentralisation programs normalised this proliferation of factories outside the 50-mile or 80-kilometre radius of Melbourne, but its negative effect was to fragment the industry itself into smaller units. Financial handouts and the promise of an untapped labour supply, together with the bumper rate of consumer spending in a generally booming economy, quite understandably dominated the thinking of manufacturers in the 1960s, allowing them to sleepwalk into the problems that would eventually jeopardise their long-term sustainability. But in the short-term, fragmenting the industry into smaller production units seemed to work in concert with the forces of the segmenting fashion market that called for smaller but plentiful runs of garments.

Many manufacturers decentralised in the early postwar period, with companies such as Latoof and Callil Pty Ltd (a large manufacturer of budget priced garments) and Prestige Limited maintaining a manufacturing presence in the metropolitan area, as well as setting up additional factories in Benalla in 1946 and Horsham in 1947 respectively. Both these ventures into regional Victoria were beset with staff shortages and much of the otherwise optimistic local newspaper coverage spoke of the difficulty in attracting and training suitable staff. Reporting also noted that both factories operated below capacity. However, these early reports did little to dampen the general enthusiasm for decentralising and most medium to large manufacturers boasted at least one regional factory throughout the decades from 1945. A relative latecomer to decentralisation, Maurice C Dowd Pty Ltd took advantage of government incentives in 1965 when it set up its small Hickory production unit in Warragul in West Gippsland.

By 1965, Dowd already had factories throughout Melbourne and beyond — in Collingwood, St Kilda, Balaclava, Brighton and Healesville. But committed to the idea of decentralisation, Dowd commenced in temporary council-owned premises in Warragul with 36 machinists, while a purpose-built factory was constructed nearby. When women’s fashion outerwear had become the company’s focus by the early 1970s, most operations were relocated to the new Warragul plant, with staff numbers growing to 200 at one stage in the company’s forty-year presence in Warragul. In an oral history interview with me, former Dowd director Michael Talbot spoke of the loyalty and diligence of his Warragul staff, who initially were mostly the daughters and wives of dairy farmers. In Michael’s opinion, “country people were the best in the world to employ.” But despite their quality, quantity was still a problem and decentralisation did not deliver the expected panacea. Michael admitted that they were always short on labour even though companies like Dowd ran extensive wellbeing and social programs in an effort to recruit and then retain staff.

The impact of labour shortages

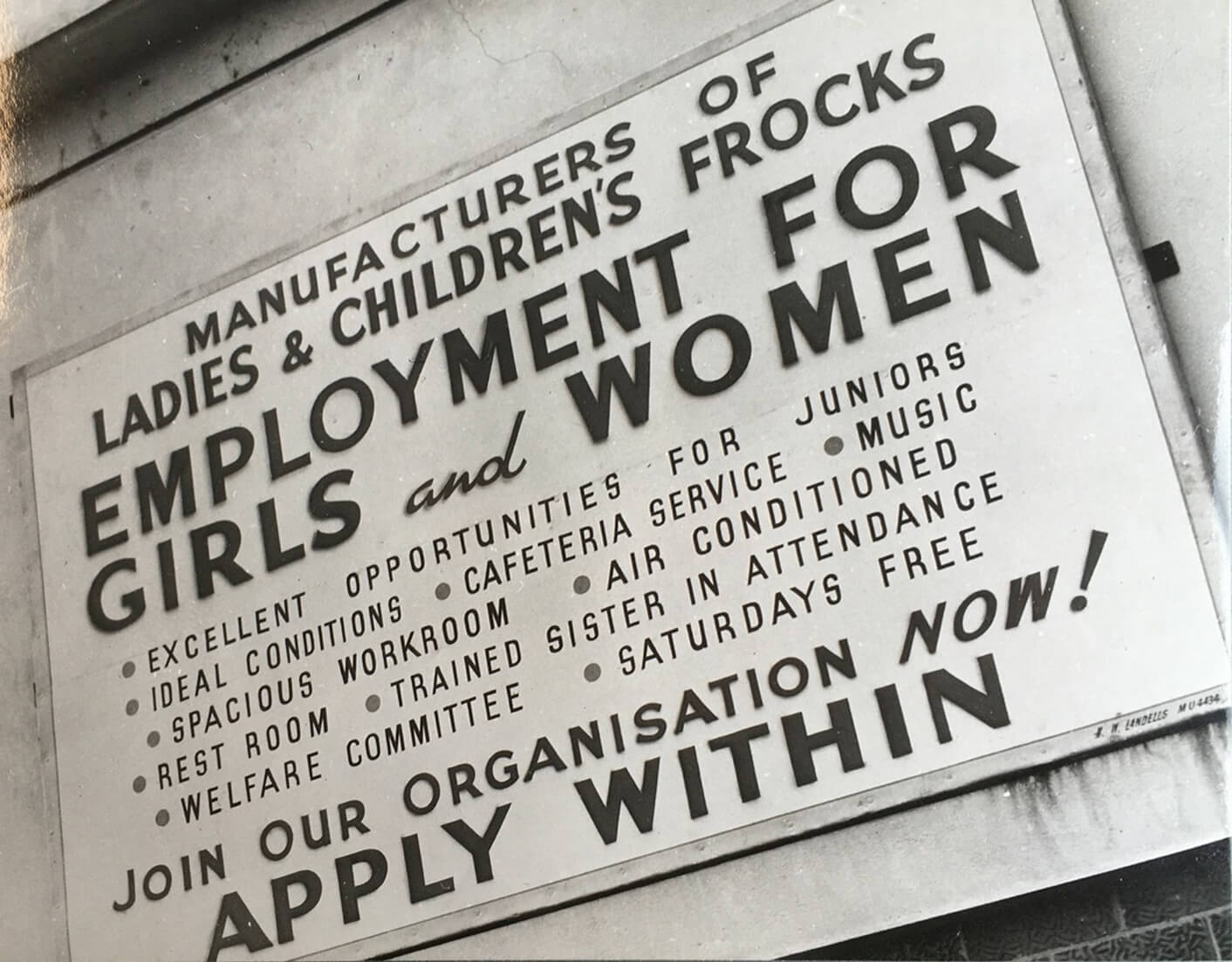

Industry-wide it was commonplace to see permanent signage affixed to factory walls and fences to attract staff — a tell-tale indicator of the short supply of labour. Signage such as that in the image below possibly dates from the 1950s and clearly attempts to counter negative perceptions that existed around the working conditions in clothing factories.

But despite the benefits offered to potential employees, the reality was that clothing factory jobs were not glamorous or well-paid. Many former workers interviewed by me for this research spoke of the monotony, the physically-taxing nature of the work, the pressures of adhering to a timeclock system and the speed of the factory conveyors. Others enjoyed the competition on the factory floor to keep ahead of management’s time and motion expectations and then relished the bonuses and kudos that a fast machinist could earn by performing more than the expected number of operations on a garment. Without exception, all former workers interviewed took pride in their work, their machine skills and the fact that their labour was a commodity always in high demand.

From the workers’ perspective, the industry labour shortage was a bonus, as it meant that they could pick and choose and come and go from paid employment at whim. Throughout most of the 1960s and 1970s, an experienced machinist was highly prized by businesses notwithstanding that the industry faced an economic downturn and the winding back of industry protection in the form of tariffs throughout the 1970s. Former Dowd machinist Helen lost count of the number of times she resigned for a ‘better’ job, before later returning to Dowd throughout her years of navigating early married life in the 1970s. Each time she chose to return, she was immediately rehired as were other former colleagues who had left to give birth and later returned throughout their years of child-rearing. As a former machinist with tailoring expertise, Marion recounted her story of resigning from a large clothing manufacturer, Toronto Fashions in West Footscray, in the mid-to-late 1970s before travelling into the Melbourne CBD for an interview with another company located in the Manchester Unity Building. Marion became lost in the corridors of this large building which, at the time, was home to many small rag trade businesses and workrooms, before knocking on the door of Captive Clothing to ask for directions to her appointment. A simple request for directions became a job interview and one firm’s loss turned into another’s gain. Captive Clothing made Marion a more attractive job offer on the spot, promising to utilise her machine skills as well as her design abilities. Marion never made it to the original interview.

Even though businesses highly prized experienced machinists, the dire need for workers precluded businesses from being over-particular in selecting staff. The reality of the labour market meant that many of those hired were unskilled, raw recruits and the training of these workers had to be factored into normal business operations. Former machinist Jill described the training regime at the decentralised Morwell factory of lingerie manufacturer, La Mode Industries in the 1960s. Here a training school was set up in a separate part of the factory catering for around 30 new recruits at any one time. Jill recalled that La Mode’s training school functioned at full capacity most of the time and this provides a window into the rate and ongoing business problem of staff turnover. Other workers described factory practices in which rookies were trained on the job on the factory floor under the eye of vigilant supervisors. These accounts speak collectively to the low tide mark on the labour pool that the industry operated within. They also flag that the constant training of new and returning workers consumed time and human resources for businesses, impacting production efficiency and creating an ongoing expense that would have underscored profitability. While impossible to quantify in monetary terms from the available sources, there is little doubt that high labour turnover and the endemic labour shortages placed a significant impost on the industry over time. From the 1970s, highly organised and competitive overseas manufacturers were beginning to make inroads into the Australian clothing market and the price point of these imported garments highlighted the weaknesses and inefficiencies within the local clothing manufacturing industry.

Conclusion

While the tariff cuts of 1973 are often regarded as the catalyst for the restructure and demise of Australia’s TCF industry, this research seeks to highlight a broader perspective. When the Whitlam labour government reduced tariffs on imports by 25 per cent in 1973 as the first step towards Australia’s entry into the globalising world, local clothing manufacturing was already unravelling. A plethora of small factories scattered throughout Melbourne and regional Victoria was making uneconomical stock in understaffed premises. Any economies of scale that might have been achieved in manufacturing for Australia’s expanding youth fashion scene had already been sabotaged by cultural change that had disrupted the traditional sensibilities of that same market. The quest for individualism and novelty, by now inherent in the youth market, meant that Australian youth and others bewitched by the ‘younging’ phenomenon, shunned the lack of choice that economies of scale necessitated. Long, economical runs of garments were, by now, the forte of offshore competitors that manufactured for the larger global youth fashion market. Thus, the spending power of local youth seeking a point of difference in the fashion market dictated the precepts of domestic fashion manufacture. Rather than strengthening the Australian industry, youth’s spending power ultimately undermined its foundations. The pursuit of individualism through fashion brought about the segmentation of the market, which in concert with structural weaknesses, such as a widespread predilection for decentralisation, coupled with chronic labour shortages, caused production to splinter and the industry to fragment into unsustainable geographic settings. On a macro level, changes occurring to Australia’s national policy on industry protection meant that the economy was redirected onto a course of transition from its inward-facing, protected position to engagement in global free trade. As the wake of the youthquake continued to wreak havoc on its already fragile structural integrity, the industry struggled to hold itself together at the seams. The combination of broader economic issues, cultural change and structural problems within the industry collectively converged to compromise the health of the rag trade and contributed to the implosion of the industry.

Author: Pauline Hastings

This research is supported through an Australian Government Research Training Program (RTP) Scholarship.

Further Reading

Arrow, Michelle. Friday on Our Minds: Popular Culture in Australia since 1945. Sydney: UNSW Press, 2009.

Frank, Thomas. The Conquest of Cool: Business Culture, Counterculture, and the Rise of Hip Consumerism. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1997.

Joel, Alexandra. Parade. 2nd ed. Sydney: HarperCollins Publishers, 1998.

Quant, Mary. Autobiography. London: Headline Publishing Group, 2012.

Rosenthal, Lesley Sharon. Schmattes: Stories of Fabulous Frocks, Funky Fashion and Flinders Lane. South Yarra, Victoria: Self published, 2005.

Steggall, Vicki. Anything Can Happen...: Sportsgirl : The Bardas Years. Richmond, Victoria: Hardie Grant Books Australia, 2015.

Webber, Michael, and Sally Weller. Refashioning the Rag Trade: Internationalising Australia’s Textiles, Clothing and Footwear Industries. Sydney, NSW: UNSW Press, 2001.