Of all household tasks, the weekly wash was the most arduous and the most unpopular. Washing machines did not arrive in most households until the 1950s and even then only performed part of the job.

The first laundry facilities were simple – a wooden or metal tub, a washing board and elbow grease. Linen was often soaped and soaked overnight in preparation for washday, ready for scrubbing the next day.

Wooden washboard, 19th century

Courtesy Mont de Lancey

Washboards were used to wash clothes by hand in a washtub. The clothes were first soaked in soapy water, then rubbed against the ridges on the washboard to dislodge dirt, before being rinsed and dried. The first washboards were made of wood, but later they could be made with ridges made of zinc or glass. They were first used in the early 19th century but continued in use well into the twentieth century. Their advantage was that they were easily portable and they soon became essential equipment in many households.

Of course, water for washing had first to be heated, either on a stove or in a copper. Sturdy linen and cotton clothing was commonly boiled in a copper, which undoubtedly was an excellent form of germ control. It also kept linens white. Grated soap or washing soda was used as the cleanser. The first coppers used wood fires to heat the water, but later both gas and electric coppers were produced. Finer fabrics like wool, silk or the new nylon had to be washed by hand and not all fabrics washed well. The colours in early cotton prints often ran in the wash, prompting women to write urgently to family in Britain seeking ‘washing cotton’ for their clothing.

After the requisite time in the copper, the items were lifted out using a sturdy laundry stick into two or three tubs of cold water for rinsing. In many laundries the last tub contained a bluing agent, to make the wash look whiter. Some households owned a mangle to wring the water out of laundry prior to rinsing and drying. Mangles consisted of wooden rollers set in a frame and were generally hand-cranked. Later smaller versions were devised to sit on the edge of laundry troughs. But regardless, doing the laundry involved a lot of lifting of heavy, wet clothes, in a steamy environment. It was hot, heavy work that could easily take all day to complete a full household wash. Hand washing was also very hard on the hands, which quickly became chapped, especially after contact with washing soda. Rough, reddened hands were often the result and were a mark of the professional washerwoman, or the woman who had to do her own washing.

A good washerwoman

In households with live-in servants, the domestic staff were expected to manage the laundry. Sometimes the mistress might help, depending on the scale of the establishment. Those without servants might still employ a casual washerwoman to come in for the day, or they might send their washing ‘out’. ‘Taking in washing’ was a common recourse for poor women, especially those with children, who could not work outside the home. In 1850s Melbourne recent immigrant Lucy Hart supported herself in this way while her husband was away at the gold fields. She could not take in large amounts of washing, as she had a young child at the time, but still managed to earn up to 30 shillings per week to keep herself and her three-year-old daughter. Lucy Hart was one of the lucky ones. Her husband John found some gold and set himself up as a carter, taking supplies to the goldfields. Before long they had earned enough to buy a small cottage near the present Carlton Gardens and Lucy wrote to her mother that she had no need to take in washing anymore. ‘I do nothing but my own work now’, she wrote proudly. For Lucy Hart this modest success fulfilled a dream. But other colonial women found the need to do their own housework demeaning. Those used to the plentiful servants of England, found aspects of colonial life very undesirable.

Taking in washing

For poor women, widows and deserted wives, taking in washing and ironing continued to be an option well into the twentieth century. Their customers included not only overburdened housewives, but the many men who lacked a wife, mother or sister to launder for them. Few men contemplated doing their own laundry, although in the topsy-turvy world of the gold diggings this was sometimes necessary. The children of these washerwomen were often roped in to help, sometimes by collecting dirty washing, or returning the clean and ironed parcel. We know about some of them because being out and about in the city exposed them to the risk of harm. One little girl, Sarah Lawton, was just 11 years old in 1904 when she was arrested by the police in Bourke Street for ‘acting suspiciously’, which translated into the constable’s belief that she was about to ‘go with a man’. She was with a friend Gertie Bigwood, who had been begging near Parliament House (or ‘cadging’ as she described it). Both girls admitted that they were following a man, who had offered them a shilling to go with him. This was a princely sum to the girls, who gave evidence that the going rate was more usually a penny. As a result of their evidence a repeated pedophile was later convicted, but the stories the naïve girls told the court meant that they too were charged, as ‘neglected children’. Both were sent to industrial schools. The accounts of the girls made it clear that girls like them were subject to repeated attempts at molestation, even when the men were known to their mothers. In her evidence Sarah Lawton, one of six children, described once delivering a package of laundry to ‘an old man in Clifton Hill’, who ‘felt me on the legs and privates and gave me a half-penny to get a lolly’. Running messages in the city could be dangerous, as these girls knew only too well.

The decline of the washerwoman and the rise of the commercial laundry

The ‘poor washerwoman’ was a common stereotype in nineteenth and early-twentieth century Melbourne. She appeared in fiction, in newspaper articles and on the stage, generally depicted as a large, brawny matron. Since washing every day probably developed strong muscles in the arms and shoulders, this may well have been an accurate depiction. But as the twentieth century progressed, washerwomen were harder to find. Newspaper articles in the 1920s and 1930s bemoaned the shortage of washerwomen, implying that finding a ‘good, old-fashioned washerwoman’ was almost impossible.

Commercial laundries stepped into the breach. The demand for laundry services saw an increasing number of commercial laundries established in the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries. In the 1890s many were run by Chinese men, as discriminatory legislation closed other employment options to them. Others just saw a business opportunity. Prince’s laundry was one example. It began in 1905 as a small concern, operating from John Prince’s home in Mentone. In 1920 he expanded into larger premises in Warrigal Road, employing many local women. His son continued the business, building a new factory on the site in the 1930s. Laundries also operated in convents, industrial schools and women’s prisons, using the free labour of inmates. Commercial laundries serviced hotels and boarding houses, but some middle-class households also began to send their larger items, like sheets and tablecloths, to the laundry, lightening the load on the housewife.

Keeping clean in ‘the slums’

Hard as wash day could be in comfortable households, it was an even greater struggle for the poor. In many inner-Melbourne suburbs laundries were often makeshift, lean-to structures tacked onto the back of houses, if they existed at all. This continued to be the case into the 1930s and forties, despite attempts to improve so-called ‘slum’ housing. One poor mother was photographed by F. Oswald Barnett washing in her ‘open-air wash house’ in Collingwood in 1935. Her galvanized iron tub was propped on a plank in an arrangement Oswald described as ‘typical of thousands’, and she was scrubbing clothes by hand. There is no sign in the photograph of either copper or wringer and the clothesline is an improvised wire attached to a verandah post. Her two children stand nearby, dressed in clothing that looks as if it might have been made from hessian bags, and the older child was probably charged with keeping the toddler out of the way. It is a wretched scene.

C’Wood [Collingwood] Open Air Wash-house, Typical of Thousands, Oswald Barnett photographer

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

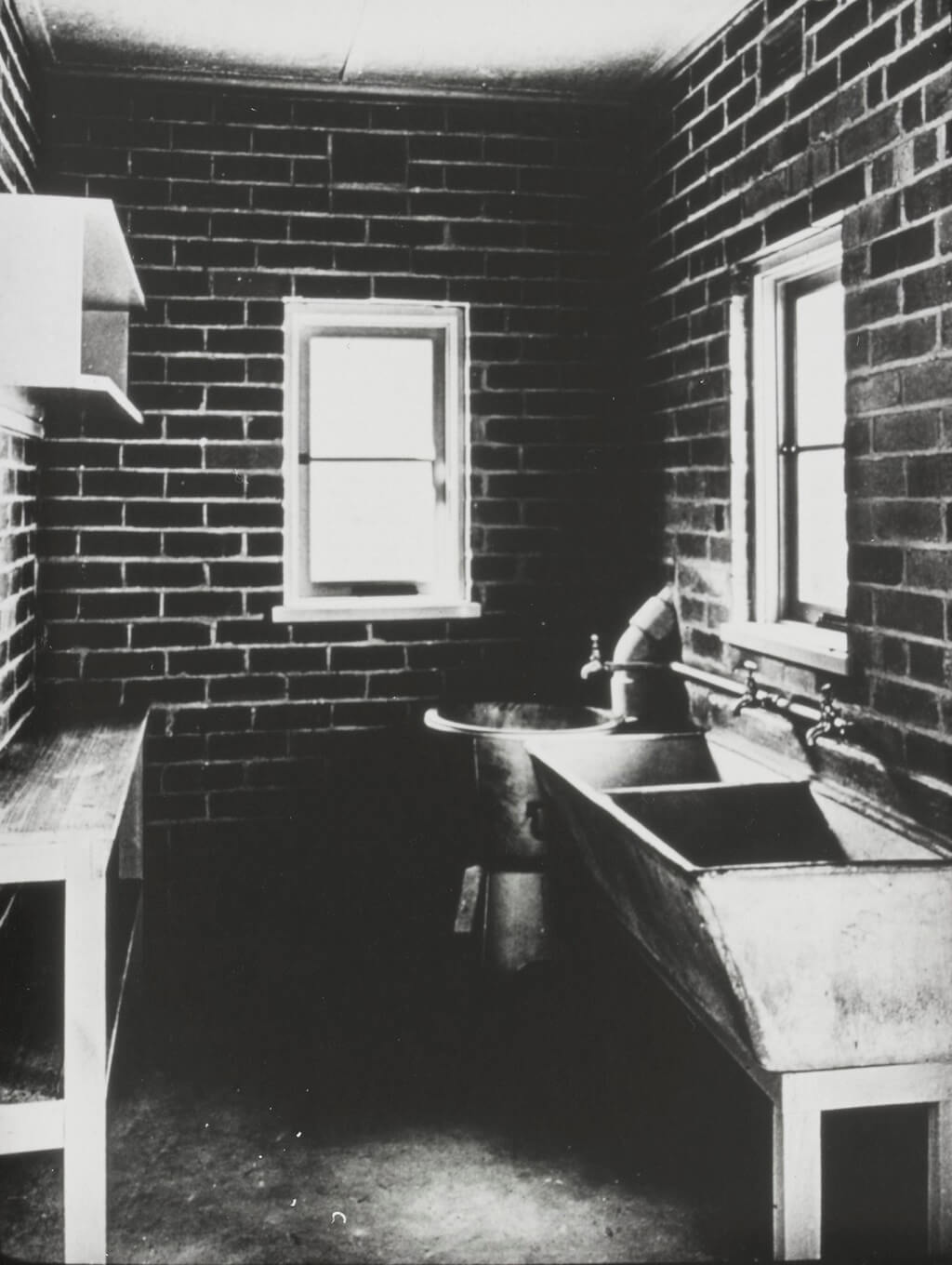

Other laundries were rather better equipped, as this photograph, also by Barnett, indicates. It shows a copper in the corner, with two laundry tubs alongside. It is not clear from the photograph whether the copper was heated by a wood fire or by gas.

The washing machine

Although rudimentary washing machines were invented in the nineteenth century and were used in some households in Australia, the laundry copper with rinsing tubs was the most common laundry equipment until after the Second World War. Even middle-class households did not always buy a washing machine until the 1950s, but then they spread rapidly. The first models were designed to work alongside existing laundry troughs and were generally used only for washing. The clothes were then passed through the attached ringer into successive troughs of cold water for rinsing. Positioning the machine alongside each trough allowed the clothes to be passed through the ringer after each rinse. This arrangement also assured that wash water was re-used for successive loads, beginning with the whites and ending with the dirtiest clothing, or cleaning cloths. Water was often still heated for the machine in an adjacent copper. It was an arrangement that used far less water than today’s washing practices, but it did mean that the washing was done in an extended, single session. ‘Washday Monday’ was a long-established tradition that continued well into the 1950s.

Advertisement for Hotpoint ‘electric servants’ Australian Women’s Weekly, 11 February 1950.

Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia

Starching

The use of starch for some linens and parts of clothing was common practice well into the 1950s. Starching produced a smooth, glossy finish to things like tablecloths or men’s shirt collars. It also made them easier to clean, because the stains and dirt generally washed off with the starch. But starching was an added process, with its own pitfalls: learning to mix and apply starch to create an even finish with no sticky lumps was part of a girl’s training as a housewife or a general servant. The PWMU Cookbook contained two recipes for starch, although both referred to the use of starch powder. It also included instructions for starching.

Starching was done as a separate process after the final rinse. It involved ‘dipping’ items in a prepared starch mix, before further wringing out and drying. Starched items were then dried and damped down again before ironing. There were grades of starching, from ‘heavy’ to ‘light’, depending on the degree of stiffness desired. This was achieved partly by the amount of starch in the mix and partly by the number of times an item was passed through the starch. Tablecloths for example were often given a stiff layer of starch, as were men’s collars and cuffs, while ladies’ frilled collars or children’s pinafores might be more lightly starched. At different times, ladies’ petticoats were starched to help support a desired shape in dress skirts: it meant that ladies sometimes rustled or ‘swished’ as they walked.

Advertising poster for Lewis & Whitty’s Diamond starch

Troedel & Co lithographers, c. 1881-90

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

Starched articles had to be ironed when damp to avoid wrinkles, so after drying such items had to be sprinkled with water, then rolled up to await the iron. It was yet another step in a laborious process. Advertisements like that shown tried to make starching appear easy, but like much housework, it required knowledge, skill and elbow grease.

There were various recipes for making starch at home, but many simply purchased commercial starch mixes like that shown, sold packaged in powdered form, ready to be mixed with water.

Automatic washing machines

Automatic washing machines, so called because they washed, rinsed and wrung out excess water in a single cycle, were popular in the United States long before they made it into most Australian homes. The Australian Women’s Weekly advertised these wondrous new machines in the 1950s, but they remained out of the reach of most households until the 1960s or later. In the meantime, a small in-between machine found popularity, largely because it was affordable and compact. It was the UK-invented ‘twin tub’ washing machine, named for its two drums- one for washing and rinsing, and a smaller, cylindrical spin dryer. The twin tub had the advantage of being able to store washing water for re-use, saving on power for heating the water, although its water-saving capacity was not yet seen as a selling point, except in areas of water shortage. The twin tub also had an extremely efficient spin dryer and some households kept their twin tubs for this facility alone, even after they upgraded to a fully automatic machine.

But it was the automatic washing machine that finally promised to free the housewife from the drudgery of washing day. At last she could load her clothes, push a button and leave the machine to do the rest – even overnight. Miraculous! And just in time too, as more and more women chose to work outside the home after marriage.

Advertisement for a Simpson fully automatic washing machine, 1957.

Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia

These were the ‘top-of-the-range’ machines in 1957, but most women had to be content with the models shown below – variants of the machines with hand-operated wringers attached and designed to run alongside the older system of rinsing troughs.

Laundry gets easier, but the volume increases

Ironically, as it became quicker and easier to manage the household wash, its volume increased. Betty Friedan pointed this out in her landmark work The Feminine Mystique, first published in 1963. Friedan argued that in making household tasks easier, so-called ‘labour-saving’ devices actually meant that standards of housekeeping rose. Sheets once changed weekly for example, might be changed twice per week if an automatic washing machine was purchased. Bed linen also changed. For hundreds of years sheets came either bleached (white) or unbleached and they were all one shape - a flat rectangle, with hemmed edges. During the nineteenth century cotton gradually replaced linen as the main fabric of bed sheets, making them easier to iron, although linen continued to be favoured by the wealthy. Bed-making practices probably evolved more slowly and were highly dependent on income, but by the early twentieth century middle-class households often washed bed sheets weekly. Common practice was to move the top sheet to the bottom and put the bottom sheet in the wash, meaning that the housewife expected to wash one sheet per bed. But in the late-twentieth century two things changed. The first was the advent of coloured, and then patterned sheets, sometime in the 1960s. These were sold in pairs and were designed to match. All of a sudden washing one bed sheet created a problem, assuming anyone cared about the sheets matching. Then the elasticated bottom sheet appeared and caught on almost immediately. There was an in-between style too in the 1960s, with elasticated corners at one end of the top sheet, but that might have been confined to the English market. Elasticated corners kept the bottom sheet firmly anchored to the mattress but meant that the old practice of moving sheets from top to bottom was no longer possible. Gradually many households moved to the practice of changing both bed sheets weekly, doubling the quantity of bedlinen in the wash. Linda Summers remembers that she and her husband Peter were given a set of ‘wildly-patterned coloured sheets’ when they married in 1972. Unlike her mother, Linda always changed both bed sheets every week.

It is not clear whether the increasingly popularity of doona covers in the late-twentieth century increased or decreased the volume of linen in the wash. If the doona cover was used instead of a top sheet and was changed weekly, its double-sided construction meant an increased load in the wash. On the other hand, tablecloths became increasingly rare, as households moved to laminated kitchen tables that did not require tablecloths to protect them. Perhaps there was some compensation!

Personal cleanliness

Standards of personal cleanliness also rose, especially in the twentieth century. Where so-called ‘white-collar’ workers might have changed their shirts once or twice weekly, changing detachable collars and cuffs more often, donning a clean shirt or blouse daily was common practice by the 1930s. From the 1920s men’s collars and cuffs were more generally attached to their shirts, making it more difficult to appear clean unless the entire shirt was changed. The dust and grime of cities, especially in the age of steam trains, meant that collars and cuffs did not stay pristine for long. All of this meant that the volume of clothing in the weekly wash increased.

Ironing

If wash day was hard work, ironing was little better. Traditionally, women washed on Mondays and ironed on Tuesdays – an arduous start to the week! Early irons were heavy affairs that were heated on the fire or stove top and used until they cooled. Most were described as ‘flat irons’ and comprised a smooth, solid metal base with either a metal or later a wooden, handle. Of course if they were heated on a stove top, it was essential that the surface of the stove was very clean, or else smuts from the stove would mark the clean linen. Sometimes ironing was done with a light cloth on the surface, to guard against either smuts or scorch marks from an iron that was too hot.

Irons were very heavy, between five and nine pounds (2-4 kilos) in weight, as at least part of the hard work of smoothing the fabric was achieved by pressure. The need to reheat irons constantly also meant that the person ironing had to stay close to a heat source, usually a stove. In summer this must have made ironing a hot, exhausting chore. It also meant that a succession of irons was necessary to avoid having to wait while irons reheated. A well-equipped household might have several flat irons, sometimes in a variety of sizes. Specialist irons were also available to iron small items, frills and pleats. In the mid-nineteenth century another form of iron, a box iron, was invented. It comprised a metal ‘box’ that was filled with hot coals or charcoal and was both heavy to use and dangerous to fill. Burns were a constant hazard. Charcoal-filled irons are still in use some parts of the developing world, where electricity supplies are unreliable.

Small flat iron, for items like baby clothing or lace and embroidery

Courtesy Mont De Lancey

Fluting iron, 1880

Courtesy Mont De Lancey

There were many forms of fluting irons, used to pleat material for the trimming popular on women’s dresses of the 1870s and 1880s in particular. Sometimes the decorative trim was removed for washing and then resewn in place afterwards.

The Box iron

In the mid-nineteenth century another form of iron, a ‘box iron’, was invented. It comprised a metal ‘box’ that was filled with hot coals or charcoal and was both heavy to use and dangerous to fill. Burns were a constant hazard. Charcoal-filled irons are still in use some parts of the developing world, where electricity supplies are unreliable.

‘Box’ iron with wooden handle, from 1852.

Courtesy Mont De Lancey

This iron was first patented in 1852. It has a wooden handle, to prevent burns when in use, and is decorated with the head of Hephaestos, the Greek god of metal workers.

Mrs Potts’ irons

Lifting heated flat irons from the stove required care as well as muscle power, and many women suffered burnt hands from the hot metal handles. Not surprisingly, when Mrs Potts of Iowa devised a solution to this problem in the 1870s, her idea caught on quickly. Mrs Potts’ irons had interchangeable wooden handles, that fitted into slots on the top of the flat iron, allowing the irons to be lifted off the stove safely. They soon reached Victoria and became ubiquitous household equipment well into the twentieth century. Irons came in many sizes, including very small irons for baby clothes, and for little girls to practice ironing their dolls’ clothes.

The volume of ironing

Despite the discomfort involved in ironing, far more items were ironed in the past than is common today. In addition to sheets and pillowcases, the weekly laundry in a middle-class household might include bathroom towels, several tablecloths, men’s white shirts, additional sets of collars and cuffs, ladies’ blouses and underclothing, night clothes and children’s clothing. Women’s dresses seem to have been washed less often, not surprisingly, as at different times their skirts were voluminous. Sometimes women’s dresses had white cotton pads in the armpits that could be removed and washed, and for many decades bodices and skirts were separate pieces, so perhaps bodices were washed more frequently, but there is very little evidence either way. Handkerchiefs were white cotton or linen and even in the 1950s and sixties were generally ironed. Until the 1920s most little middle-class girls wore white pinafores to keep their dresses clean. These could be quite elaborate affairs, with embroidered insertions and frills, all of which required careful ironing.

Children of Neerim South State School photographed on Arbor Day 1908.

Reproduced courtesy Public Record Office Victoria 14562, P 12, unit 2.

Many of the little girls wear white pinafores. Note that the boys are pictured doing the digging and hoeing!

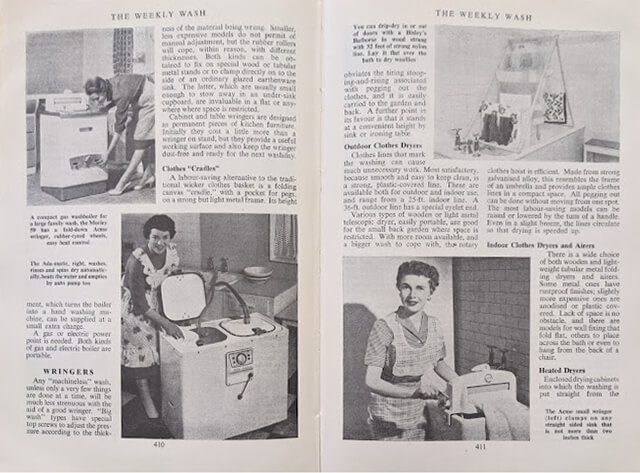

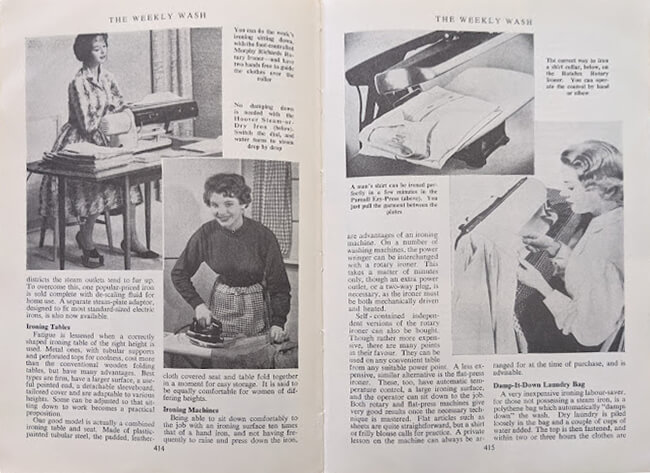

Despite the obvious danger of burns, girls were taught to iron from an early age. Little girls might begin by ironing the handkerchiefs, graduating to more difficult items as they became more competent. Folding ironing boards were available in the United States in the later-nineteenth century, and were certainly available in Australia by the 1920s, but many housewives seem to have ironed on flat tables until the 1950s or even later. There is quite an art to ironing a shirt on a table (rather than an ironing board) and girls were usually taught how to do this by their mothers. Other less fortunate girls were taught laundry and ironing skills in Victoria’s industrial schools, before being sent into service. That was what happened to Sarah Lawton and Gertie Bigwood. Gertie was 14 when she was sent into service and was still a state ward. Books of household management also included detailed instruction in ironing methods, often with illustrations. This book was published sometime in the mid-1950s – 1960s and included reference top both ironing tables and ironing boards.

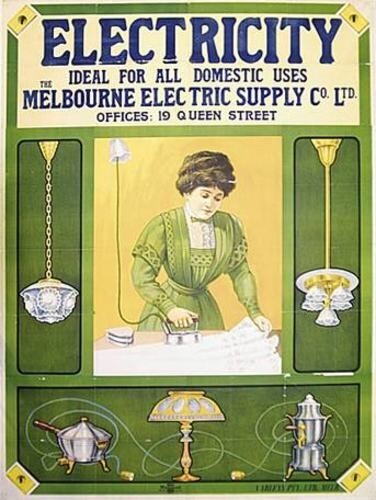

The advent of electric irons and then electric steam irons revolutionized ironing. The first electric irons were patented in the United States in the late-nineteenth century, but they did not really catch on until much later. In Victoria households began to be supplied with electricity from the early years of the twentieth century, but in most homes this was confined to lighting. Few homes had additional power sockets until the 1920s or thirties and early electric irons were actually designed to plug into light sockets! Much later in the twentieth century the manufacture of clothing in synthetic materials and then knit fabrics further reduced the need for ironing, while the Women’s Liberation Movement provided a feminist context for women to leave their irons in the cupboard.

Poster, Melbourne Electric Supply Co. c. 1910

Reproduced courtesy Museum Victoria

Note the iron plugged into the lamp socket.