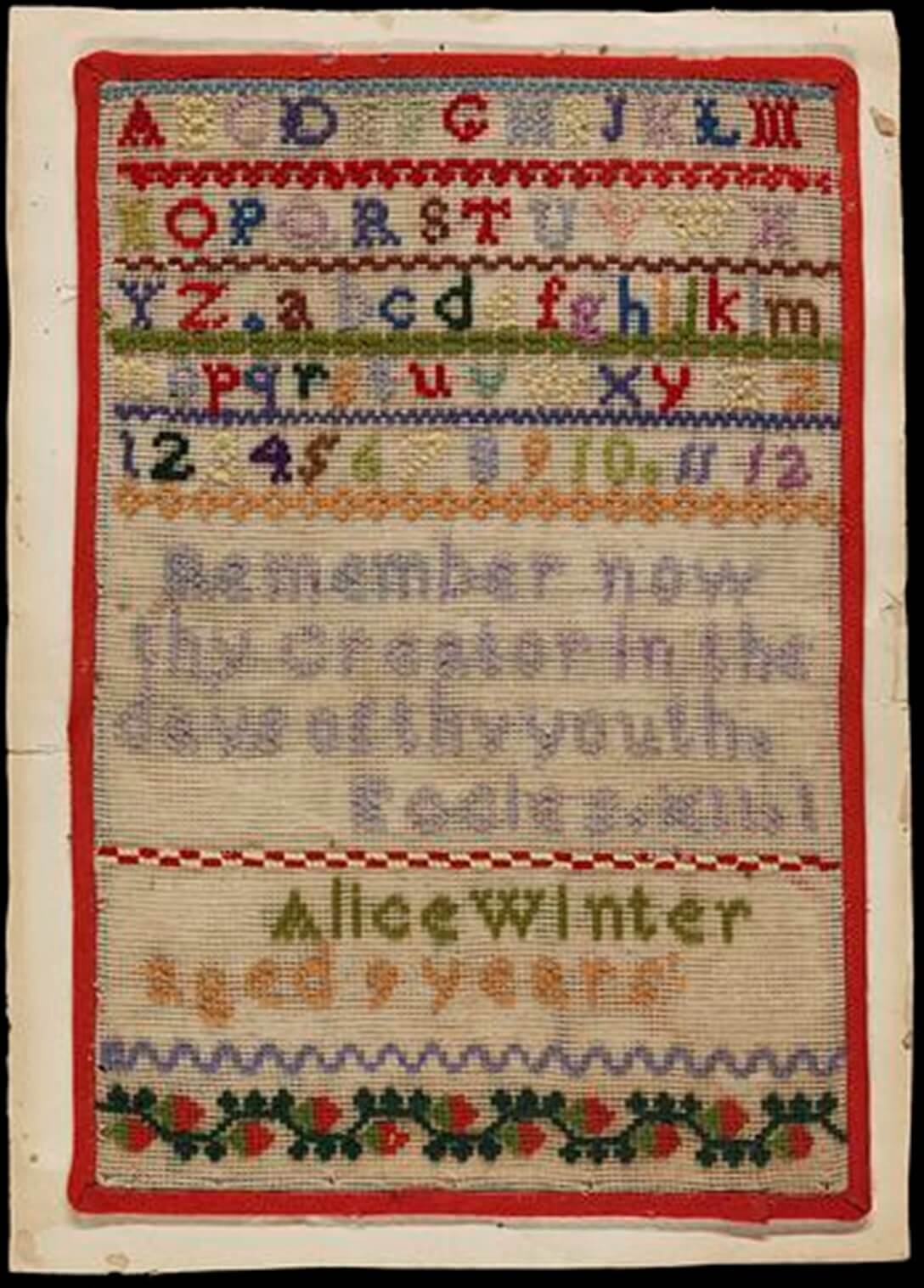

Sewing was a crucial skill for most women until well into the twentieth century. Although some clothing could be bought, (men’s clothing and women’s coats in particular,) almost all children’s clothing and much women’s clothing was made at home, stitch by stitch. Household linen was also made at home, with fabric for sheets and towels sold by the length, ready to be hemmed. Little girls were taught to sew from a very early age and some wonderful samplers in museum collections attest to the range of stitches they were expected to learn.

At first everything was sewn by hand and could involve hours and hours of careful stitching. Just as an indication of the time involved, we once estimated the number of stitches in the skirt of a crinoline dress (c. mid-1850s) in the Old Treasury Building’s collection We counted over 5,000 tiny stitches and that was only in the skirt! Keeping a family clothed, from underclothing to outerwear, could easily be a full-time occupation for a busy mother. And then there was the mending – an endless succession of worn socks and stockings, men’s collars and cuffs to be ‘turned’, and children’s torn or outgrown clothing to be repaired and recycled, from what must have seemed like a bottomless mending basket.

Even wealthy women sewed. It was fashionable for young women to embroider and to make useful items for household members. Companionable evenings could be spent in this way in middle-class households. But such women were often also capable of making clothes, or refashioning dresses and hats to update them, should the need arise. Sometimes professional dressmakers were hired by the day to come to the home to help. Wealthy families might even employ a full-time needlewoman. Eliza Chomley (née à Beckett) remembered how her early life, in the wealthy à Beckett household, involved little in the way of work. As she wrote: ‘I think we ought to have had more duties at home, but, with plenty of servants, including a resident needlewoman, and plenty of money, I had no cares.’ (Eliza Chomley, ‘My Memoirs’, Mss State Library Victoria) Later, she lived a comfortable life on the Victorian goldfields, where her ‘work’ often involved hours spent completing projects in cross stitch, worked in brightly-coloured wool on a canvas ground. But for many less-privileged women, needlework could mean many hours of plain sewing and mending, mostly completed after other housework was done.

An evening at Yarra Cottage, Port Stephens 1857 by Maria Brownrigg

Watercolour and collage

Reproduced courtesy National Portrait Gallery

The sewing machine

Not surprisingly, the invention of mechanical sewing machines in the mid-nineteenth century had a huge impact. The first machines were intended for commercial use and did not succeed, largely because of the determined opposition of tailors who feared (rightly) for their jobs. The sewing machine claimed to reduce the time required to make a man’s shirt from 14 hours to less than two, threatening to make many tailors and dressmakers redundant. But opposition was soon overcome and by the mid-nineteenth century a domestic version of the sewing machine was in mass production. The best-known was the Singer sewing machine, which was soon exported all over the world. It was often the first item of domestic machinery to be purchased in any home. Singer also initiated the practice of time payment, purchase by instalments, allowing those who could not afford the purchase price all at once to pay it off gradually.

The sewing machine was a huge boon to the busy housewife. The first models were powered by the user pressing a treadle, requiring no additional power source. Later electric models were patented, but the treadle machines were still common in many households long after electricity was connected to the home.

Woman using a Singer sewing machine, c. 1910

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria