Although both moralists and the press continued their campaign against Chinese gambling houses, the most popular form of gambling actually took place elsewhere — on the race tracks and later in illegal off-course betting shops. These pastimes were also condemned by the wowsers, who kept up a lively campaign to curtail such activities. At first on-course bookmakers used an informal system to take and record bets on thoroughbred racing, but in 1882 the Victoria Racing Club introduced a licensing system for bookies. In the same year the arrival on the scene of the English bookmaker Robert Sievier established a system for taking and recording bets, issuing tickets to punters. His system quickly became standard and would remain in place for more than a century.

Some bookmakers lived flamboyant lives, flaunting their wealth. Sol Green, another Englishman, was famous for driving to the track in the 1930s and forties in a gold-plated Rolls Royce, although he also gave significant sums to charity. But others preferred to operate in the shadows, making a living in the illegal trade of off-course betting. Of these, one of the most successful and undoubtedly the best known, was John Wren.

The betting ring at Flemington. By Carl Kahler artist, 1890

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

In contrast to the gambling houses of Little Bourke Street, the crowd at Flemington included Victoria’s privileged classes.

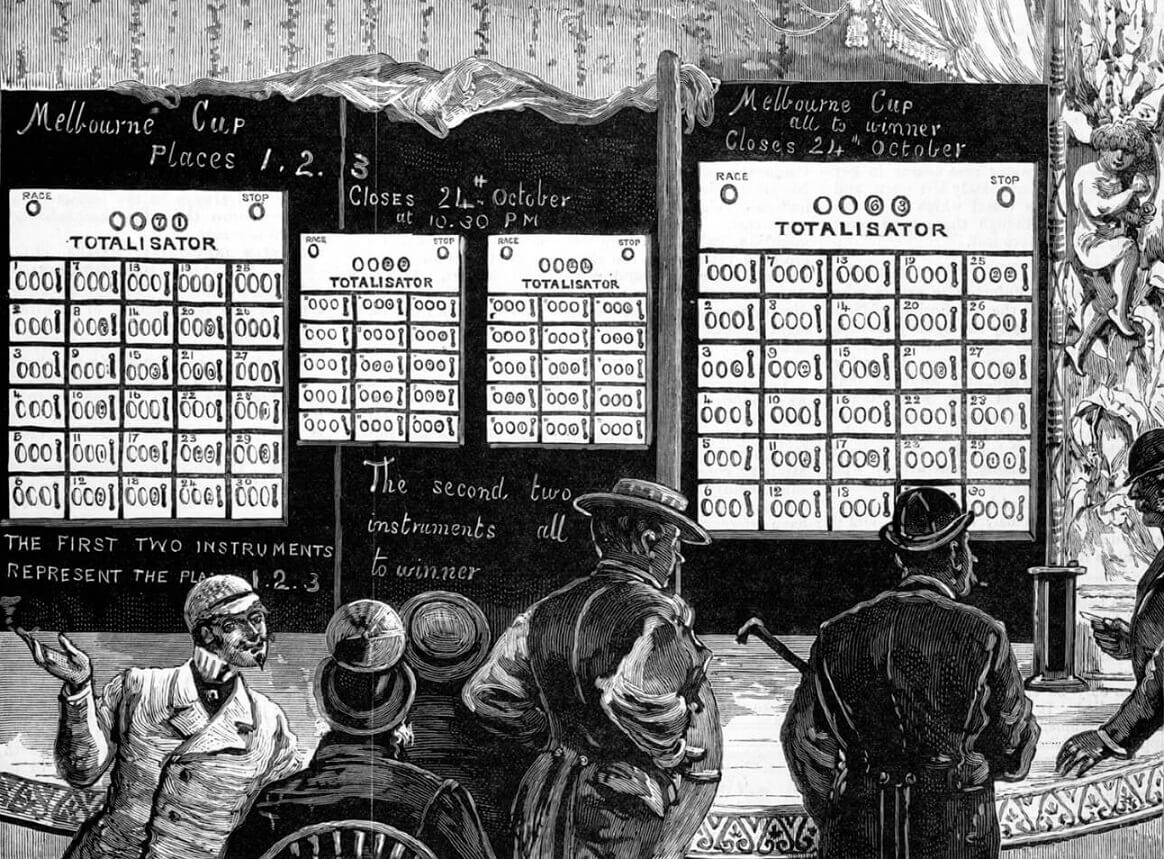

‘The Totalisator, Sportsman’s Club, Bourke-Street’

Wood engraving, The Australasian Sketcher, 18 November 1882

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

Gentlemen also gambled on the races in various private clubs, although they were rarely subjected to police raids. This engraving shows a system of gambling known as the ‘totalisator’, a parimutuel system that determined the dividend paid by the total value of bets placed on each horse. More bets placed meant a lower dividend paid, while the house took a commission. Bets placed with bookmakers on the course were issued with set ‘odds’.

John Wren (1871-1953)

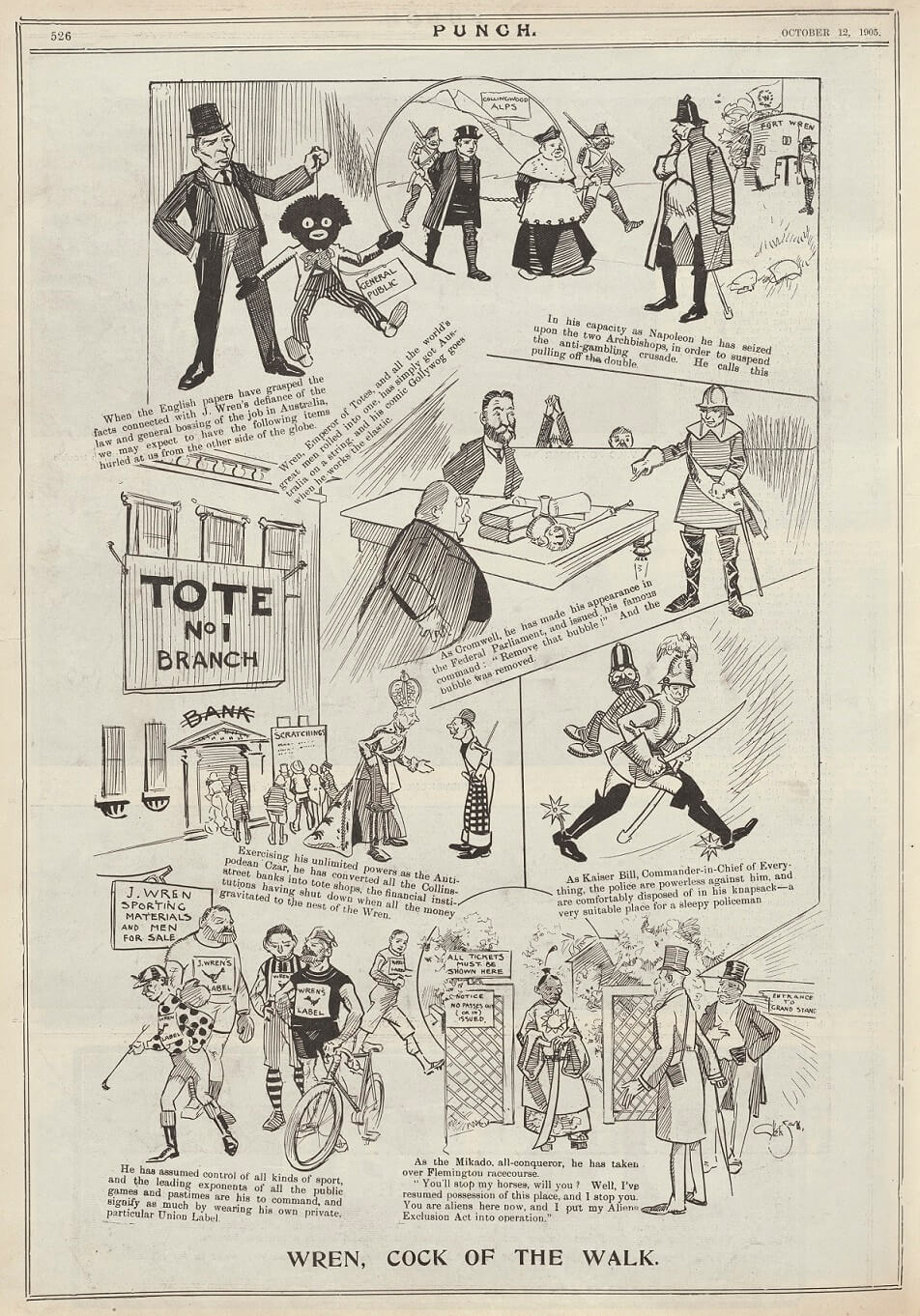

Off-course betting was strictly illegal in Victoria, though it was tolerated in gentlemen’s clubs like the Sportsman’s Club. However it could be extremely lucrative. One man who turned off-course betting into a hugely-successful business enterprise was John Wren, a working class lad from Collingwood, who left school at 12 to work in a wood yard and then as a boot ‘clicker’ (or finisher). Wren seems to have managed an occasional betting ring in his spare time, but when he lost his job in the 1890s depression, decided to turn his interest into a full-time business. It was soon spectacularly successful. Wren’s ‘tote’ in Collingwood operated from 1893-1906 on a parimutuel, or totalisator system (hence the shortened name ‘tote’), with the house taking a cut on every bet. Although illegal, Wren’s tote had a reputation for honesty in dealing. His tote was also something of an impregnable fortress, with buildings within buildings, making it complex and difficult for the police to get search warrants, while a complex network of spies and informers kept a watch out for police patrols. Almost certainly Wren also had informers within the police force and probably maintained corrupt telephone operators. In later years the tote was said to be netting Wren a profit of £20,000 per year — a fortune in anyone’s terms — and it allowed him to diversify into many legitimate business ventures. Rumours circulated about his influence in political circles and within the Catholic Church. By 1905, when this cartoon was published, the tote had made Wren immensely rich and he seemed unassailable. The police tried repeatedly to infiltrate his organisation as successive attempts to raid his premises in Collingwood failed. In the meantime, his legitimate businesses flourished alongside his illegal betting shop. In this set of caricatures Melbourne Punch poked fun at the extent of Wren’s commercial and (assumed) political influence.

‘Wren, Cock of the Walk’, Melbourne Punch, 12 October 1905

Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia

Triumph of the wowsers

But opposition to illegal off-course betting slowly gained ground in Victoria. Opponents like the redoubtable W H Judkins made Wren and his growing business empire a focus of their campaign to tighten the gaming laws and increase the powers of the police to enter premises. In 1906 they succeeded, and the passage of the Lotteries, Gaming and Betting Act (1906) finally gave the police the powers they needed to shut him down. Wren closed the doors of the Collingwood tote immediately. By then a millionaire, he had already diversified into legitimate racing, trotting, boxing and other interests (including newspapers) spread across several states. He also cultivated an image as a public benefactor, supporting local charities in Collingwood, the Catholic church and in the Irish Catholic community. Meanwhile his family lived in splendour in Studley House in Kew, a far cry from his Irish Catholic Collingwood origins. Debate has continued ever since about the extent of Wren’s power and influence in both the Australian Labor Party (ALP) and the Catholic church. Historian Chris McConville argues that his political influence, while considerable at times, was also contested, often successfully. The socialist candidate Maurice Blackburn was one who prevailed against the Wren faction’s attempt to defeat him at pre-selection in the Fitzroy branch of the ALP in 1925. In later life Wren became more conservative and while he never tried to move in exalted social circles in Melbourne (undoubtedly wisely), his children all attended élite Catholic schools. Studley (or Wren) House is now part of Xavier College. On Wren’s death in 1953 he left a huge and complex estate, which took his executors two years to unravel.

SP Bookmaking

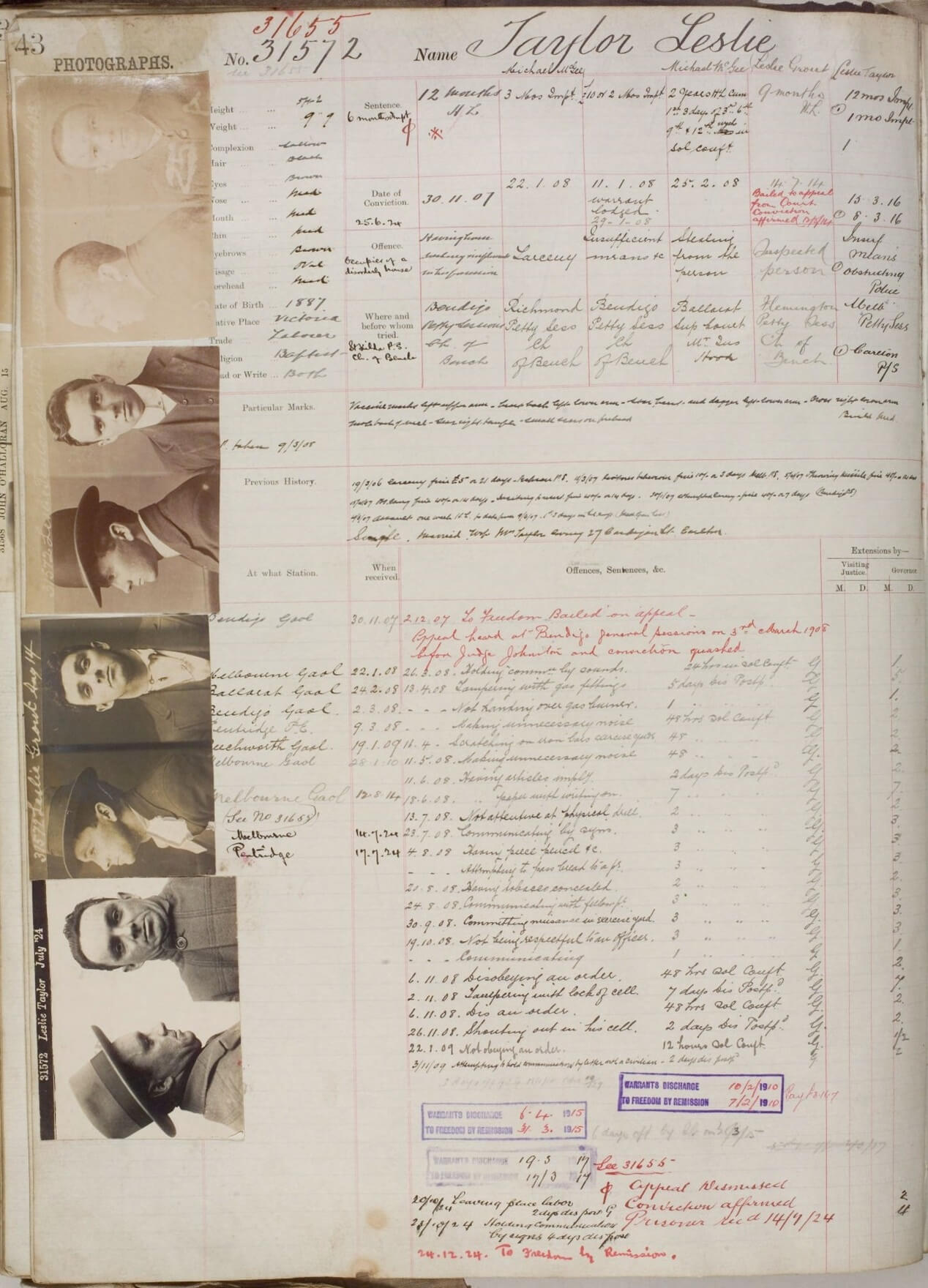

While the wowsers celebrated their apparent victory over Wren, illegal off-course betting quietly reorganised. Ironically, the refusal of the anti-gamblers to sanction legal off-course betting, created an environment that allowed clandestine betting operations to flourish. Increasingly they were controlled by criminal gangs, and mobsters like the notorious Joseph Theodore Leslie (‘Squizzy’) Taylor (1888-1927). Squizzy Taylor was a thug with none of Wren’s redeeming qualities. His criminal activities included robbery, illegal liquor sales, prostitution and drug dealing, along with off-course betting and protection rackets. He was implicated in several murders and served terms in prison for theft, although he later developed a successful jury-rigging network which might have influenced his acquittal of other charges. Eventually his cocaine dealing brought him into conflict with a rival Sydney gang, which culminated in a shootout in Carlton in 1927. Taylor died of his wounds on 27 October 1927.

Prison register for Joseph Theodore Leslie (‘Squizzy’) Taylor

Reproduced courtesy Public Record Office Victoria

The state embraces gambling

As the influence of the wowsers waned after the Second World War, government cast covetous eyes on the profits of gambling. In 1961 they created the Totalisator Agency Board (TAB), which assumed control of off-course betting on horse racing. It was immensely profitable. Officially, the creation of the TAB saw the end of clandestine off-course betting, although historians like Chris McConville suggest that it may have continued to some extent until the computerisation of the TAB in 1981 finally made the system more secure. Government also appropriated the once-despised format of the lottery and a weekly ‘flutter’ with a lottery ticket is now common practice for many worthy citizens who certainly would not regard themselves as ‘gamblers’. Mr Judkins and his ilk would have been horrified, but the TAB and lotteries together netted government handsome profits in the intervening decades, ushering gambling out of the shadows and into the public realm.