It is difficult to be precise about the number of gambling premises operating at any one time in Little Bourke Street, although various estimates were published in the newspapers from time to time. In July 1872 the Age published extracts from a report on gambling in the ‘Chinese quarter’ issued by the Society for the Promotion of Morality. These worthies visited various premises on the evening of 27 July, in company with a police detective, and concluded that issuing lottery tickets had become ‘part of the business of every Chinese storekeeper, and is pursued with little intermission throughout the day.’ They observed ‘a great variety of classes in attendance’ at the drawing of the lotteries, which were conducted ‘almost hourly’. In many houses the game of fan-tan was also played with great concentration and was said to be played continually, ‘both day and night’. It is probably important to assume a bit of hyperbole here, but clearly gambling was a regular pastime in the street. By 1902 an article published in the Herald suggested that there were 50 gambling shops in Little Bourke Street between Swanston and Russell streets alone, with others in Little Collins Street. (Herald, 4 April 1902, p.2)

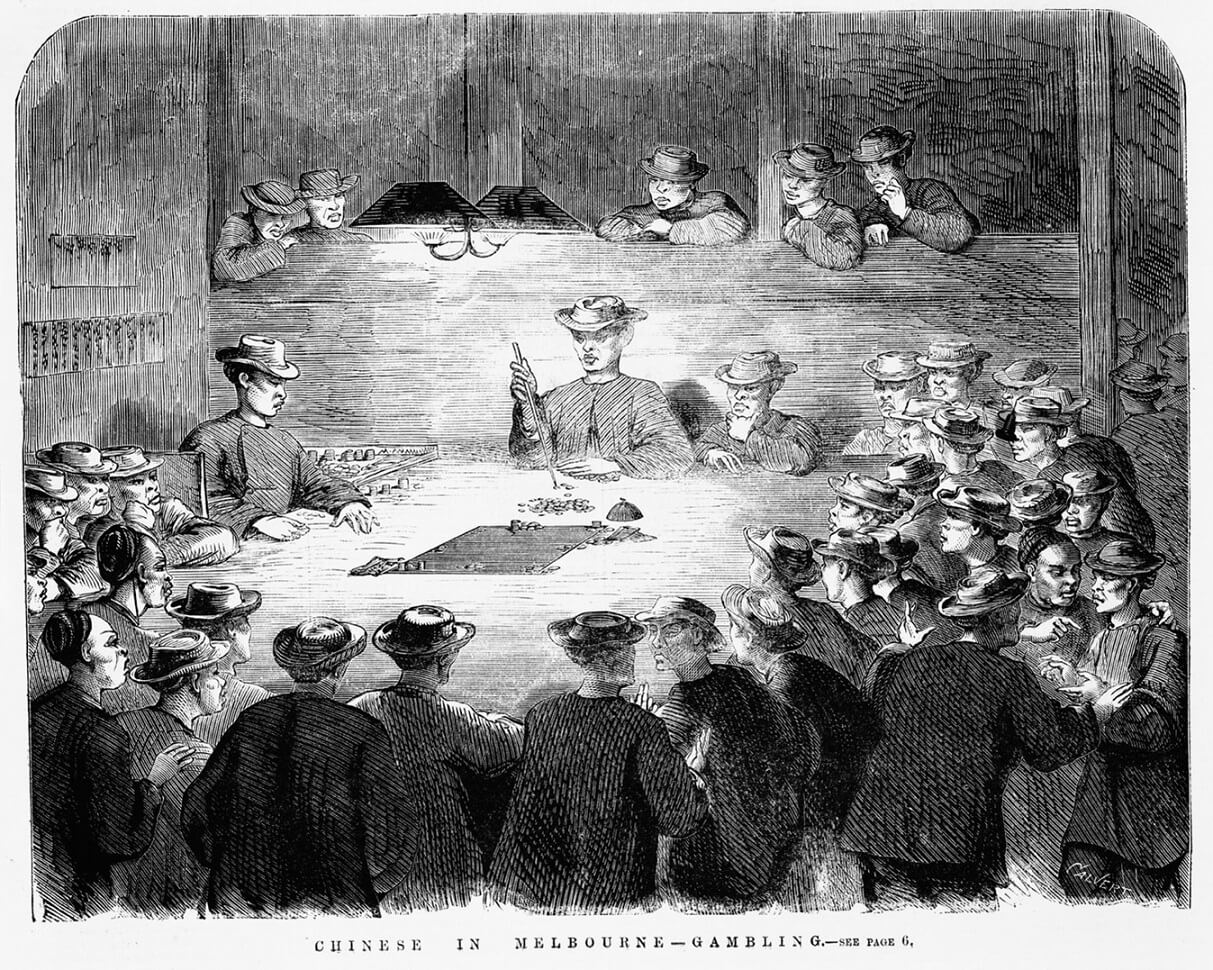

‘Chinese in Melbourne – Gambling’, wood engraving by Samuel Calvert, 1868.

Published in The Illustrated Australian news, 8 August 1868.

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

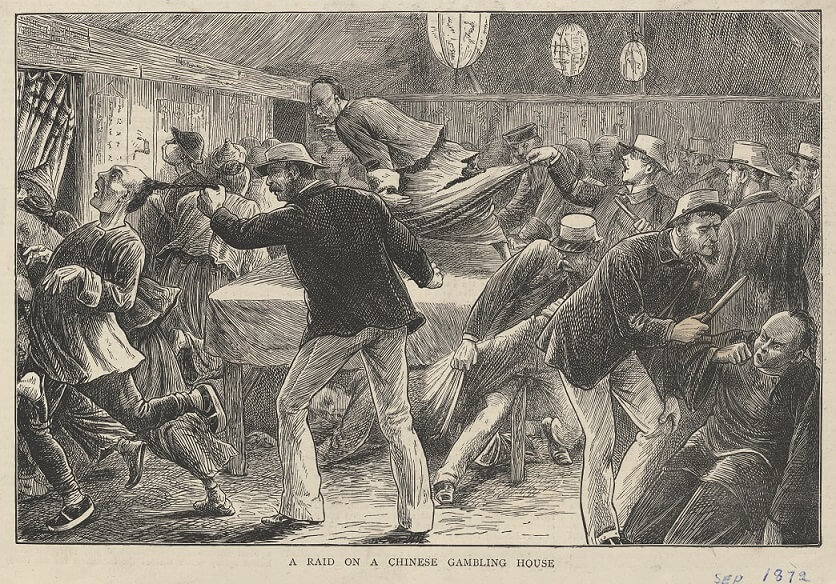

The police conducted raids on these premises from the mid-1850s and often used force to arrest those on the premises. In May 1857 the Argus described one such raid in detail:

A furious scuffle took place, and the officers had to use their sticks and whips pretty freely, many of them being several times knocked down. Ultimately, however, about nineteen or twenty Chinese were secured and safely lodged in the watch-house. … The conduct of the detective officers, whether a conviction be obtained against the culprits or not, deserves much credit, and to the boldness and skilfulness of their attack may be attributed the capture of so many offenders. (Argus, 18 May 1857, p. 5)

Repeated attempts were made to strengthen the legal powers of the police to arrest the proprietors of gambling houses and to secure convictions, with little discernible success. In frustration in May 1876 the Herald newspaper published a scathing article condemning the ‘incompetence’ of the Crown Solicitor, after a recent attempt to amend the Police Offences Statute Act became embroiled, yet again, in legal challenge in the Supreme Court.

It is not long since we congratulated the country on the final passing of the Police Offences Statute Amendment Act, which was specially designed to put an end, once and for ever, to the existence of a system of Chinese gambling, as baneful and demoralising in its effects as it was widespread and insidious in character. No sooner had the Governor given his assent to the measure, than the Chinese put up their shutters, closed their ticket shops, and stopped their unlawful proceedings. A fortnight afterwards, they took counsel from their legal advisors, who discovered, or pretended to discover, a loophole for the Mongolian offender — a serious flaw in the Act. Thereupon, a few of the lottery banks recommenced business and the ticket shops reopened. (Herald, 17 May 1876, p.2)

A raid on a Chinese gambling house, 1872

Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia

Melbourne’s Chinese attracted particular attention from police waging war on all illegal gambling.

Despite legal obstacles, raids on the Chinese gambling houses were a regular occurrence for the next several decades. In March 1892 the Argus reported on one such raid, described as the ‘most severe and successful raid upon Chinese gambling dens yet known in the colony.’ Its target was the Chinese lottery ‘banks’ operating in Little Bourke Street, a gambling game that the Argus insisted was ‘devised especially for the benefit of Europeans.’

The Chinese themselves do not indulge in it, but it has grown so popular amongst Europeans that as a rule from eight to ten banks are in active operation, and the lottery is drawn on the average once every hour.

In a coordinated raid, plain-clothes police entered three separate premises, arresting 73 people, both Chinese and European, on charges of ‘being the occupants of gaming-houses.’ It was a busy session the next day at the City Court! (Argus, 14 March 1892, p.7)

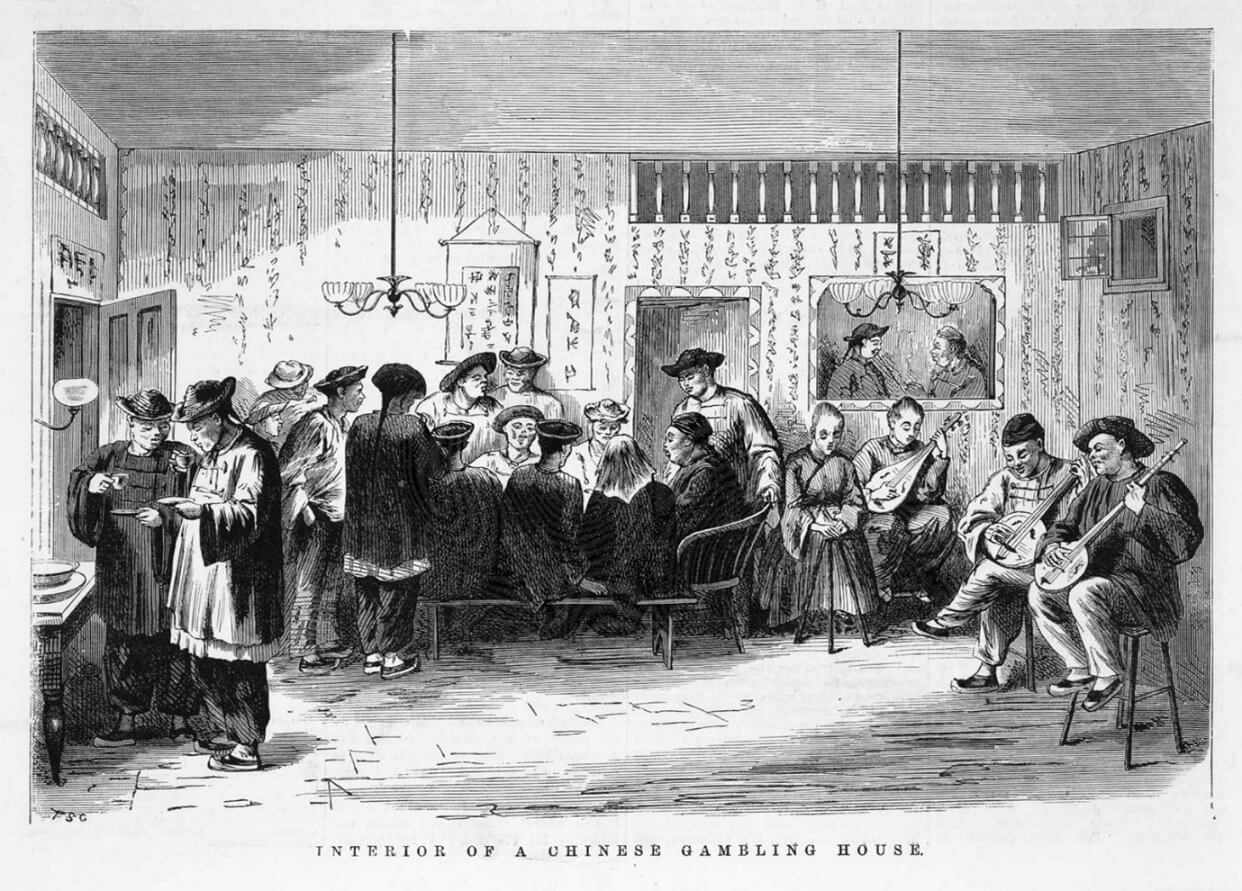

‘Interior of a Chinese Gambling House’ by Thomas Cousins, 1871

Engraving published in The Illustrated Australian news for home readers, 9 October 1871

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

Although this engraving shows Chinese patrons only, it is clear from newspaper reports that many Europeans attended these gambling houses.

However the increasing willingness of the cashed-up proprietors of lottery banks to use legal means to thwart the police was a constant source of official frustration well into the twentieth century. It was said that the bankers joined forces to ensure that offenders had legal representation in court and that the fines of those convicted were paid. One of the difficulties facing the police was probably the challenge they faced in identifying culprits correctly. Police and court records make it plain that the police struggled with naming their offenders, who probably soon realised that it was easy to hood wink them. One record associated with a man named On Gew Hooey, identified at least 7 ‘alternate’ names — Ah Sing, Hoey Ah Gin, Ah Gin, Ah Gen, Hooey Ah Gin, Lee Loon, and Ah Gan. Nevertheless, many Chinese men served terms of imprisonment, which could range from weeks to months, depending on the severity of the charge. Meanwhile opposition to gambling came from both within the Chinese community and without. The Melbourne Young Men’s Christian Association claimed in 1904 to represent a Chinese friendly society, whose 500 members worked actively to oppose gambling within the community although they knew themselves to be in a minority. (Herald, 19 April 1904, p.2.)

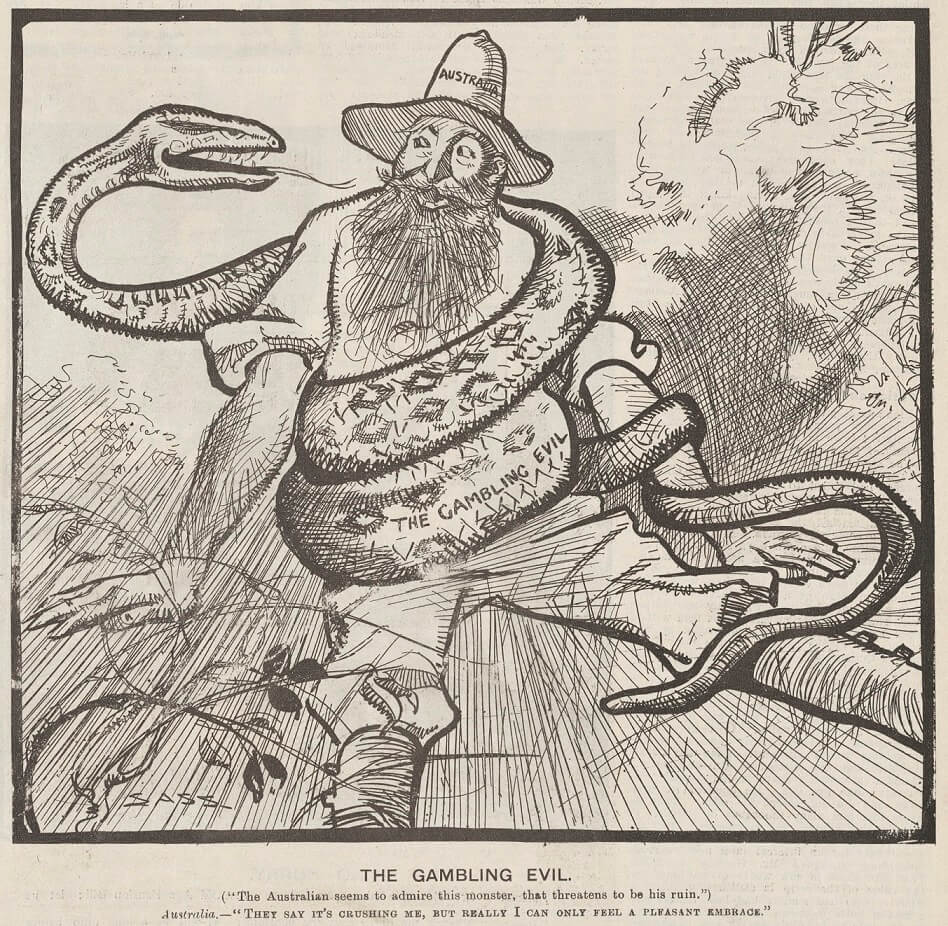

‘The Gambling Evil’, Melbourne Punch, 3 August 1905

Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia

Of course the Chinese were not the only ones to conduct gambling on their premises and European proprietors also attracted police attention. In October 1919 one Henry Stokes was charged with permitting illegal gambling on his property in Richmond. It was not his first offence: there were previous court appearances in 1916 and 1917 that we know of. In vain his solicitor, Mr Larkins, tried to argue that Stokes had undertaken to convert his premises into a garage and to promise that he would not permit gambling there again, but his comments also made it plain that Stokes was considered a serious criminal.

In certain near-hysterical quarters… Stokes is considered a deep-dyed criminal, a dog. He is accused of a great many things. I hope you will pronounce a lenient sentence as Stokes is willing to give ample satisfaction that he will not again be guilty of the offence now before you. (Argus, 14 October 1919, p.8)

The magistrate was unmoved and imposed the maximum fine of £500.

‘Dens of iniquity’

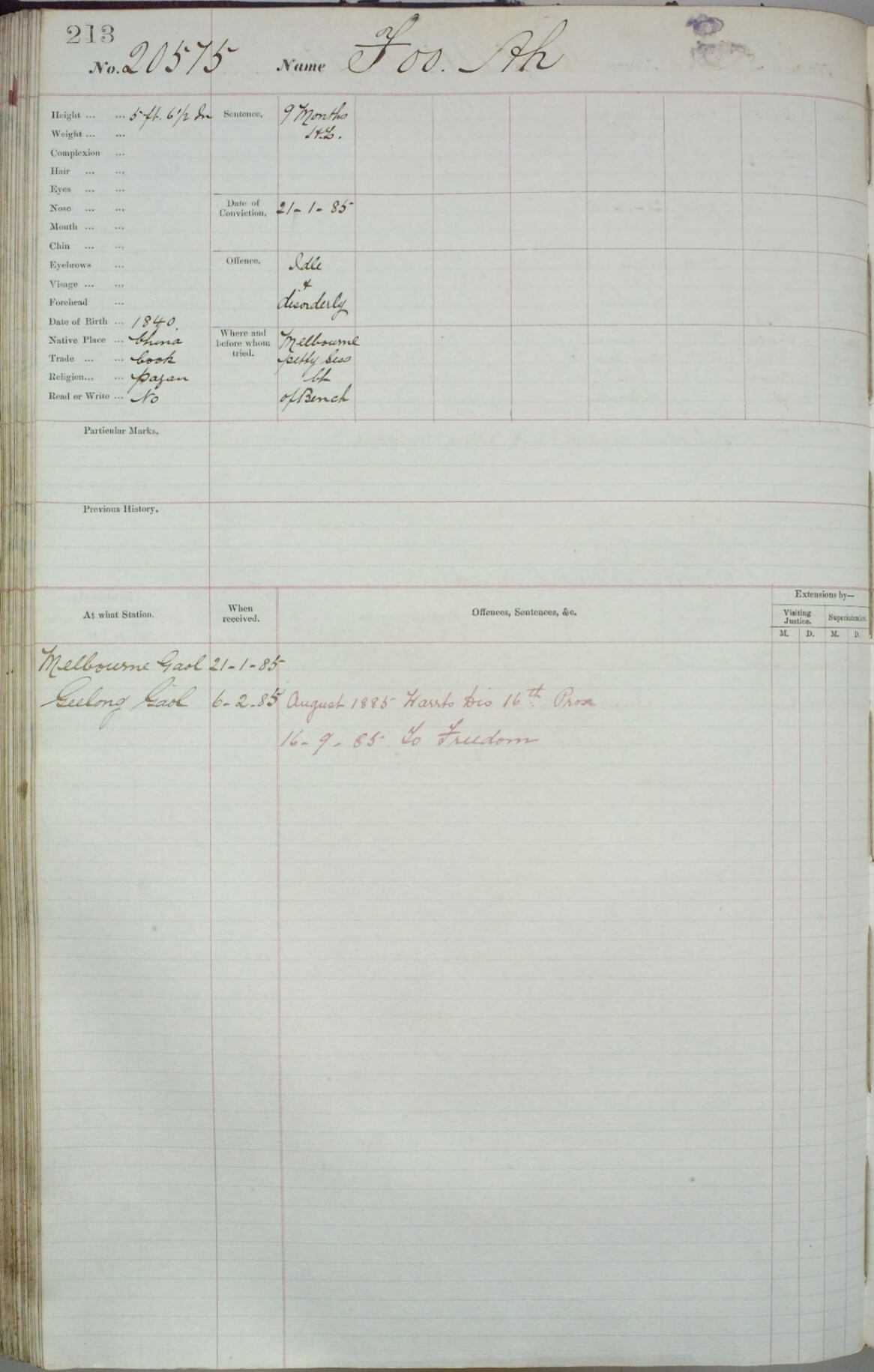

Opposition to gambling, along with other forms of ‘vice’, intensified in Victoria in the early decades of the twentieth century and the Chinese gambling houses continued to attract more than their share of police attention. But the concern of the moralists grew to fever pitch whenever young women were discovered on the premises of these houses. Invariably they were assumed to be in ‘moral danger’ and were arrested routinely merely for being there. Some of these women may well have been sex workers, using the gambling houses as convenient locations for their trade, although a common charge was also that of ‘vagrancy’, even where it was clear that a woman regarded the house as her residence. Lurid headlines fanned the flames — ‘Chinese dens of vice’ (Age,1885), or ‘Visit to Chinese dens: “Soul-shuddering immorality”.’ (Argus, 1910) In January 1885 for example, Ah Foo was accused of keeping a disorderly house in Market-lane.

The police evidence showed that the place was a common resort of lewd characters of the lowest class, male and female, European and Chinese, and a nuisance to the neighbourhood. The prisoner was committed to gaol for nine months. (Argus, 22 January 1885, p.5)

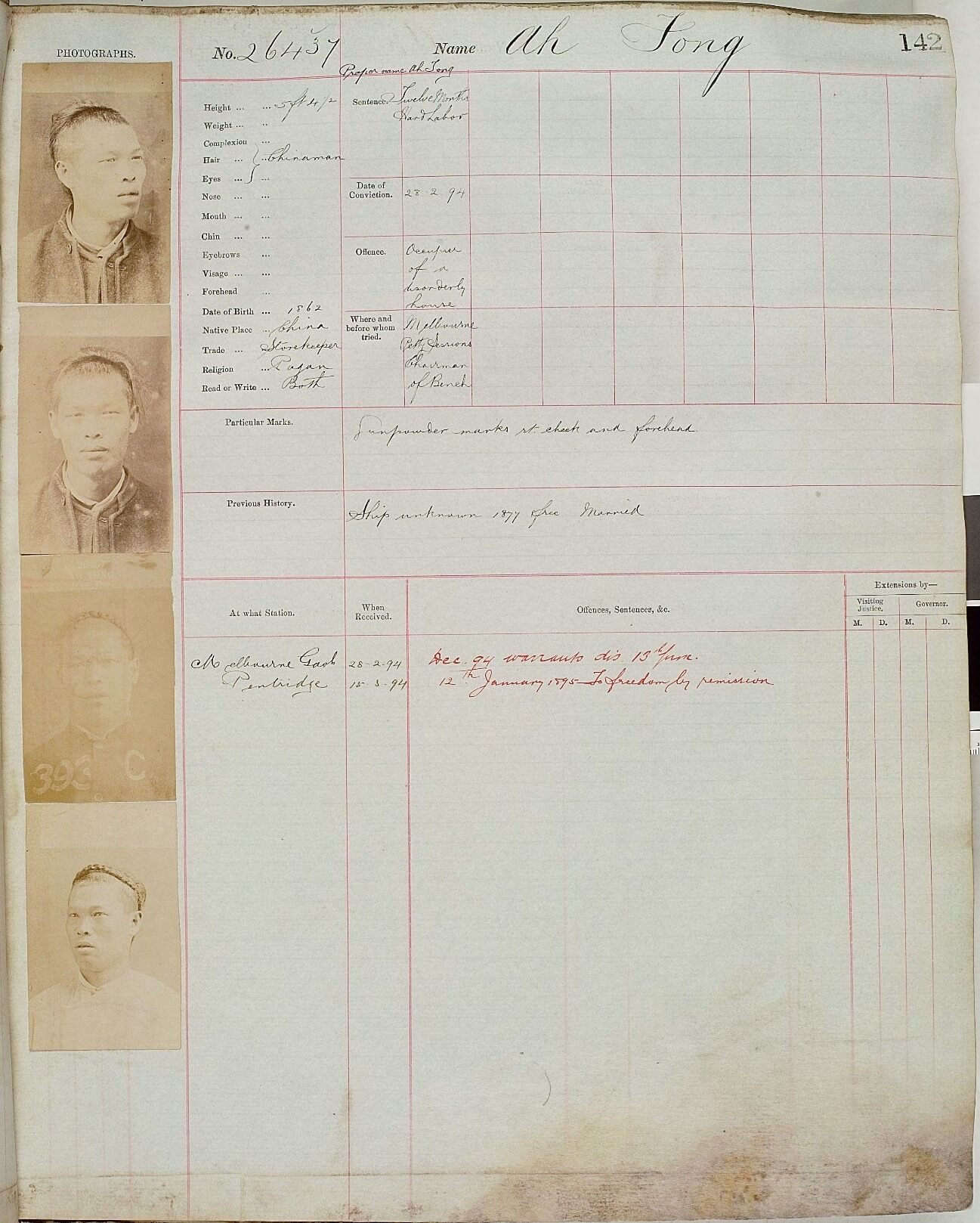

Similarly, Ah Fong was convicted in February 1892 for being the ‘occupier of a disorderly house’ and sentenced to twelve months hard labour at Melbourne Gaol and then Pentridge.

Prison register for Ah Foo

Reproduced courtesy Public Record Office Victoria

Prison register for Ah Fong

Reproduced courtesy Public Record Office Victoria

Colourful language fanned the flames of moralistic fervour. In August 1910 Mr W H Judkins spoke to the faithful at Wesley Church in Lonsdale Street of his recent harrowing visit to the ‘Chinese dens’ of Little Bourke Street.

From the gambling shops, he and a friend had gone elsewhere, and had there seen so much open immorality that it had made their souls shudder; immorality of so fearful a character as to make one wonder whether, in comparison with modern Melbourne, Sodom and Gomorrah had not been highly moral places. (Argus, 15 August 1910, p.6)

As a result a disproportionate number of Chinese men were probably convicted of offences like ‘keeping a disorderly house’, as well as gambling.