The career of Elizabeth Downey, aka Isabella Allinson

Although we know there were abortionists active in Melbourne throughout this period, it is almost impossible to know how many there were, let alone how many women sought their services. Generally, their activities only came to light when their patients died and even then, most could not be traced. Abortionists were careful to send any woman who showed signs of infection to the Women’s Hospital, where most maintained a strict code of silence. Since both abortionist and patient had committed a crime, most women invented other explanations for their condition, unless literally on the point of death. Even then, strict rules of evidence surrounding the recording of so-called ‘dying depositions’ made it very difficult for the police to prosecute abortionists successfully. However, we do know something of the career of one well-known abortionist, since she was prosecuted repeatedly in the period between 1897 and 1910. The story presented here has been pieced together from newspaper accounts of her trials and from the capital case file associated with her last court appearance.

Elizabeth Downey (also known as Isabella Downey or Isabella Allinson) carried on a lucrative practice as a nurse and abortionist in North Melbourne then Carlton throughout the 1890s and 1900s. She may well have set up in practice before this, but if so, she evaded the notice of the police. Her career came to an abrupt end in 1910, when she was finally convicted of wilful murder, after the death from sepsis of a young woman on her premises. But in the previous 13 years she had been tried on no less than 14 occasions for similar offences. The history of her court appearances reveals in painful detail the perils faced by both patient and abortionist in Melbourne at the time, but also underlines the great difficulty faced by the police in prosecuting such cases successfully. Detailed evidence presented at her last trial hints at the complex network that supported this clandestine trade and helped to conceal it in the shadows of the city.

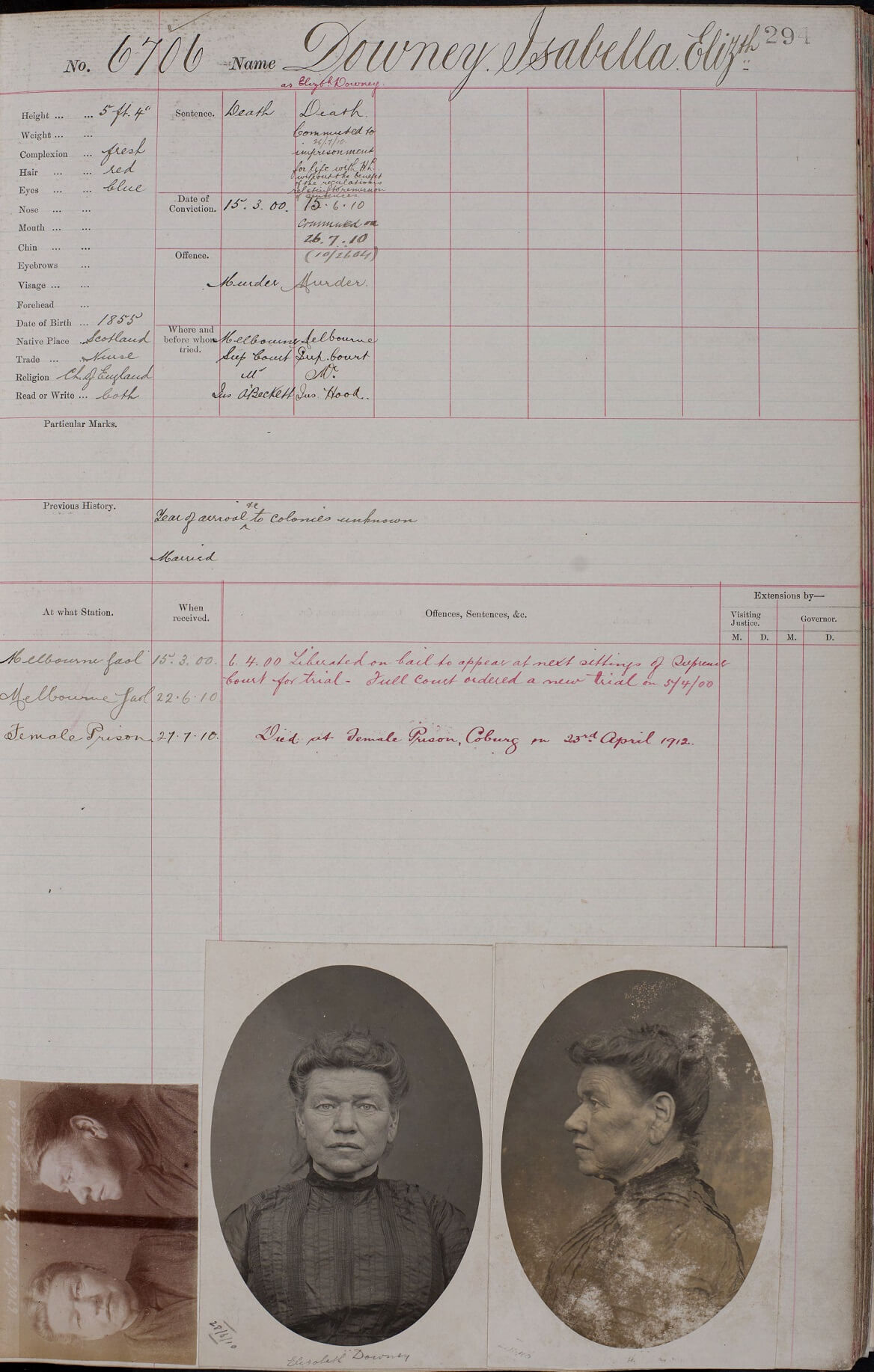

Central Register of Female Prisoners – Isabella Elizabeth Downey

Courtesy Public Record Office Victoria

Elizabeth Downey seems to have begun her career as a nurse in the 1870s, although it was not a very auspicious beginning. While we cannot be certain it was the same woman, it seems likely that she was indeed the junior nurse identified as Elizabeth Downie, who gave evidence at an inquest in 1876. The inquest was inquiring into the death of a Mrs Conley, who died following an operation at Alfred Hospital in which a sponge and forceps were left inside her. The surgeons all insisted that it was the responsibility of the nurse assisting to count the sponges, although nothing was said about the forceps. Downie claimed to have identified the fact that one sponge was missing and to have informed one of the nurses, but only after the patient was put back to bed. The hospital subsequently tried to conceal the fact that mistakes had been made, although the inquest found that they were not the cause of death. (Argus, 9 November 1876, p.10) Whether this experience persuaded Downey to set up on her own account we cannot know, but at some point over the next 20 years she established herself as a private midwife/nurse, and as an abortionist. Although the police were evidently aware of her activities, she managed to avoid further contact with the law until 1897.

The death of Mary Jane Henry (24 October 1897)

In October 1897 Elizabeth Downey was approached by Mary Jane Henry, a 24-year-old married woman who wanted an abortion. Downey allegedly performed an operation on her in her house in North Melbourne, then repeated the procedure the following day. Mrs Henry was accompanied by a ‘lady companion’, a Miss Angelina Glen (or Glenn). On the day following the second procedure Mrs Henry became ill and was in such pain that her husband sent for a local doctor. Downey also visited her patient that day but became ‘agitated’ and left by the back door when the doctor arrived. According to an early report in the Age, she ‘took away with her a certain instrument and it is alleged asked deceased and Miss Glen not to say she had called.’ (25 October 1897, p. 6) Doctor Embley treated Mrs Henry, who told him that her condition had come about by ‘working a sewing machine’. Sewing machines at this time used a treadle action, and she may have known that treadmills used as punishment in women’s prisons had been associated with miscarriages. However the doctor plainly did not believe her and instead rang the detectives’ office to report an ‘illegal operation.’ When Mrs Henry died on 24 October Miss Glen told the detectives about the visit to Mrs Downey and they immediately went to her North Melbourne house to interview her.

At first Downey denied any involvement but backed down when confronted by Miss Glen. The detectives also found ‘a number of instruments wrapped in brown paper’ and proceeded to arrest her ‘on a grave charge of performing an illegal operation, and thereby causing the death of Mary James Henry, a married woman aged 24.’ At this point Downey allegedly broke down and asked to be left alone for 10 minutes saying that ‘she would do away with herself and save the police any further trouble.’ However, when asked for a statement, her husband advised her to ‘say nothing.’ She was conveyed to the City Watch House. In 1900 Downey was probably aged in her early forties. The newspapers described her as a ‘married woman, aged 43.’

Angelina Glenn was the principal witness at the coroner’s inquest held on 29 October 1897. She told the court that she had gone with Mrs Henry to Elizabeth Downey’s house, where Mrs Henry went upstairs with Mrs Downey for ‘three or four minutes’. The fee was three guineas. On the way home Mrs Henry told her that Downey had used an instrument on her. The jury’s verdict was that Mrs Henry died ‘from the effects of an illegal operation performed by Elizabeth Downey’, who was promptly committee for trial at the Supreme Court.

Downey’s first murder trial took place before the Chief Justice on 23 November 1897. The evidence from the inquest was repeated, but the defence counsel subjected Angelina Glenn to sustained cross-examination, which revealed that she had worked for Elizabeth Downey at about the time of the alleged operation. In the absence of a more explicit interpretation of this exchange, which was reported without further comment in the Herald, it seems likely that the intent was to discredit the main witness for the prosecution. There may have been an implication that both Glenn and Henry were part-time prostitutes too, but that was not spelled out. It was clear however that the Chief Justice was unimpressed by the Crown case. In the absence of a sworn statement from the deceased, the evidence was all hearsay, and the Chief Justice informed the jury that although there was evidence that Mrs Downey was paid for her services, there was no proof of the nature of those services. Not surprisingly, the jury returned a verdict of not guilty. (Herald, 23 November 1897, p. 4 & Argus, 23 November 1897, p. 10)

The case of Ellen Butler

Just over two years later Elizabeth Downey was in court again. This time the patient was Ellen (or Nellie) Butler, a single woman in her early twenties, who worked in a tobacco factory. She died in the Melbourne Hospital on 3 February 1900 after a procedure performed at Downey’s residence in late January. It seems that Butler returned to her father’s house after the procedure and was recovering well when Mrs Downey visited her there some days later, but she deteriorated quickly after that. Dr George Horne was called, diagnosed peritonitis and advised that the patient should be transferred to the hospital. However, he also informed the detectives, who immediately attended, and, on the advice that ‘death was imminent’, took down a ‘dying deposition’ from the patient. According to an account in the Age, this deposition was recorded ‘in the presence of Mrs Downey’, who was then arrested ‘on the charge of using an instrument with intent.’ A search of her premises once again identified ‘several appliances generally used in such cases.’ (Age, 5 February 1900, p. 6) At the subsequent inquest, which took place over two days, the detectives also alleged that Downey had initially ‘admitted having been guilty of malpractice, at the girl’s earnest request.’ Ellen Butler’s deposition confirmed this account, adding that ‘the nurse had refused to accede to her request at first’, but had relented on her third visit ‘out of kindness.’ The jury returned a verdict of murder and ordered that Downey be committed for trial. (Argus, 9 February 1900, p.9)

What followed developed into an extraordinary legal battle. Perhaps as an indication of the determination of the authorities to put a stop to Downey’s activities, the Coroner initially refused bail. At a subsequent hearing bail was agreed, but set at two sureties of £1,000 each, despite protests from Downey’s defence counsel that such a sum was ‘unreasonable, and the friends of the accused were not in a position to obtain such high bail.’ Seasoned magistrate, Mr Panton, was unmoved. (Argus, 6 February 1900, p. 9) An appeal to the Supreme Court to vary bail followed but was unsuccessful. However, this was just the beginning of a legal ordeal that stretched ultimately over four murder trials held over six months.

The trial began in the Criminal Court before Justice à Beckett on 21 March and was reported in both the Age and the Argus on the following day. Elizabeth Downey was charged on this occasion under the name of Isabella Elizabeth Downey. Some confusion seems to have surrounded the precise age of the deceased, who was variously reported as being aged either ‘about 23 years of age’ (Age) or ‘22 years of age’ (Argus). It was noted that she had lived with her father at Clifton Hill and worked in a tobacco factory. Evidence reported from the trial largely reflected that presented to the Coroner’s Court, except that once again defending counsel, Mr Purves QC, focussed on trying to deflect blame away from his client and onto Ellen Butler herself, with or without the assistance of a woman named Mrs Margaret Kemp, who claimed to be a neighbour. He argued that Kemp’s evidence was inconsistent with the statement she had given the Coroner, in which ‘you swore that she had secured a certain result herself.’ He also protested that insufficient notice had been given before the deposition was taken, preventing his client from seeking legal advice. The detectives however repeated their evidence that Downey ‘had admitted performing an operation, for which she was paid £2.’ One note of uncertainty was introduced by Dr Henry Mollison, whose post mortem had revealed the presence of Bright’s disease, a kidney condition he suggested would have made her more susceptible to peritonitis.

The defence case focussed on trying to substantiate the claim that Ellen Butler had attempted to abort herself before seeking out Mrs Downey. A woman who worked as a domestic servant for Downey insisted that Ellen Butler admitted to her that she had ‘used an instrument, and taken drugs.’ In her own statement Downey admitted only that ‘out of pity for her’ she had ‘performed a minor operation, and burned the instrument afterwards.’ In considering their verdict the jury asked only whether Ellen Butler was ‘in a rational state’ when she made her deposition. They were assured that she was and then returned a verdict of guilty. As the judge pronounced the mandatory death sentence the court erupted: several of Downey’s women friends and relatives ‘broke into violent sobbing, one of them being carried out in a hysterical state.’ (Age, 22 March 1900, p. 6 & 23 March 1900, p. 7; Argus, 22 & 23 March 1900, p. 6)

However Mr Purves was not ready to concede defeat. He gave notice immediately of his intention to raise a point of law regarding the notice given of the intention to take Ellen Butler’s deposition and the opportunity afforded his client to take legal advice. His appeal was heard by the full court before the Chief Justice, Justice à Beckett and Justice Hodges and reported in the press on 6 April. The justices upheld Justice à Beckett’s decision to admit the deposition as evidence, but determined that the provisions of the Justices Act, under which the deposition was taken, ‘were not applicable unless an information had at the time been laid against the accused.’ On this technical point, they ordered that the conviction be quashed and the matter retried. (Argus, 6 April 1900, p.3; Age, 6 April 1900, p.7)

The second trial May 1900

The retrial took place at the Criminal Court on 29 May. Most of the evidence presented was the same, but there was additional evidence from Dr Eugene Anderson, former medical superintendent of the Women’s Hospital. Dr Anderson observed that he had ‘never found a case of septic peritonitis develop after four days. If a patient was well on the fourth day, he did not expect any mischief afterwards.’ Once again it was suggested that Ellen Butler had taken ‘lots of medicines of various kinds, including washing soda, pills and other things.’ The jury retired at 5.30 pm but was unable to agree. They were discharged and a third trial was ordered. (Age, 30 May 1900, p.8; Argus, 30 May 1900, p.9)

The third trial

Downey was back in court at the end of June, to hear the same evidence presented. She repeated her statement that ‘she used an instrument on her for a perfectly legal purpose, to relieve her of pain.’ The jury was reported to have ‘been locked up for the statutory six hours’, but once again failed to agree and the matter was referred to a fourth trial. At this point the Crown Prosecutor, My Finlayson, QC apparently vowed to continue with trials until a jury was found to agree, although he admitted that this was ‘unique in the annals of the Victorian law courts.’ The Age report noted: ‘Mr Finlayson, QC, Crown prosecutor, states that he believes such a thing has never occurred before anywhere.’ The Argus reported similarly:

For all other offences but murder the Crown invariably enters a nolle prosequi after a third trial without a verdict. In the case of Mrs Downey, the Crown prosecutor (Mr Finlayson) states his intention of going on, unless otherwise directed, until a jury is found to agree. (Age, 29 June 1900, p.6; Argus, 30 June 1900, p.15)

The fourth trial

The fourth and final trial took place on Friday 20 July. It was listed for 18 July initially, but a note in the Argus reported that ‘her previous counsel refused to accept the fee which the Crown offered for her defence, the accused being destitute.’ It was no wonder! (Argus, 19 July 1900, p.4) Although her defence asked for a month’s deferral to brief the new barristers, they were given only two days. Ultimately, she was defended by Mr Eagleson and Mr Maxwell, although the instructing solicitor, one Mr Corr, remained the same. After a long day of evidence, the jury retired at 6.30 pm. At 8 pm they returned with a verdict of not guilty and Elizabeth Downey was finally released. It had been almost six months since the first trial. A summary note in the Argus also revealed for the first time how close she had come to conviction at each of the previous retrials, when first two jurymen, then one stood against the majority. By any account it was a lucky reprieve and the drawn-out drama might have persuaded most people to retire. Perhaps Mrs Downey saw no alternative to reversing her ‘destitution’. Whatever her reasons, she was soon back in business.

The death of Emily Chandler, 1905

There is no further record of Elizabeth Downey’s activities until July 1905, when another young woman who had sought her services became ill after a procedure. Emily Chandler, a 28-year-old waitress from Seymour, claimed to have visited Mrs Downey’s house on 25 June. A procedure was performed on her for a fee of £2/5/- and some days later she went to stay at a house in Sydney Road Carlton, owned by a Mrs Sefton, described as a friend of the family. Emily was very ill while with Mrs Sefton, but conflicting evidence was presented about whether she confided in her. Mrs Sefton sent for Emily’s mother, who arrived promptly, but was told only that her daughter was suffering from a very bad cold. In the meantime Mrs Sefton sent for a doctor, who advised that Emily should be removed to the Melbourne Hospital. She died in the hospital on 3 July, but before she died she gave a statement to police in which she identified Elizabeth Downey. On this occasion the police were careful to notify Downey that they intended to take a sworn statement, which took place before a police magistrate. Evidently the police had learned from their previous procedural mistakes. Downey was charged in the first instance with ‘malpractice’, or ‘having used an instrument for an illegal purpose’, but on Emily Chandler’s death the charge became murder.

An initial inquest into Emily Chandler’s death was held on 4 July at the hospital morgue, after which Downey was charged with murder. The newspapers described her as ‘an elderly woman’, though she was probably then aged about fifty (estimates of her age vary). Once again the magistrate, Mr Panton, refused bail, but this was later amended on appeal to the Chief Justice and set at £500, with additional sureties of £600. However, when the inquest resumed on 18 July it soon became apparent that Emily Chandler may have been delirious when she made her statement to police. She claimed to have visited Downey with a sister named Millie, although she had no sister of that name, and did not recognise her brother when he came to see her. The hospital doctor called to give evidence also admitted that Emily might have ‘caused a certain result’ herself and, in response to a question from the defence counsel about the instruments found at Mrs Downey’s premises observed that: ‘he would expect a midwife to have in her possession certain of the instruments produced.’ Once again, the code of silence maintained between client and abortionist was evident. In her evidence Mrs Sefton admitted that Chandler had told her an instrument was used on her, but that she said nothing to the attending doctor because she ‘did not want it to be known.’ When interviewed by the detectives at the hospital, Emily insisted that she ‘didn’t know the woman’s name or the street where she lived,’ although she apparently identified Downey later (although not by name). Throughout the proceedings Downey insisted: ‘I don’t know the party at all. I never saw her in my life’. In the end the Coroner saw little point in pursuing prosecution. He was recorded as concluding:

It was perfectly plain that an infamous crime, that of endeavouring to kill a living child, had been committed. In this particular case, not only had that crime taken place, but the unfortunate mother died too. He did not think it likely that deceased performed the operation herself. Right through it appeared that deceased tried to conceal the identity of the person who operated on her and it did not appear likely that she was not aware of the name of this person.

Nevertheless, he did not believe that the evidence against Downey was sufficient to convict her and ruled that the murder was committed by ‘some person or persons unknown.’ Once again, Downey was free. (Age, 3 July 1905, p.5 & 5 July 1905, p.7; Herald, 4 July 1905, p.1 & 18 July 1905, p.3)

1907 – Vida Patullo & Miriam Rankin

1907 was not a good year for Elizabeth Downey. In March she faced two charges simultaneously, both initially for ‘illegally using an instrument’, but one charge quickly became a murder charge, when her unfortunate patient died. The first charge related to an abortion performed on Mrs Miriam Rankin, who was described as a ‘young, married woman’. Downey was out on bail for this charge when she was rearrested and charged with the same offence performed on a young, single woman named Vida Patullo. When Vida died on 1 April this charge became murder.

The inquest on Lilias Vida Helen Patullo (known as Vida) began on 3 April before the District Coroner Dr Cole, but was adjourned to allow Mrs Downey, who was described as ‘a nurse living in Carlton,’ to attend. Evidently Downey had moved from North Melbourne in the interim. The inquest resumed on 6 April. Vida Patullo was described as a domestic servant, although later reports called her a ‘bar maid’, who worked at the Council Club Hotel on the corner of Queen and Lonsdale streets in the city. Evidence was presented by Detectives Burvett and Sainsbury and by Vida’s sister Adeline that Vida and her sister had visited Mrs Downey for a procedure and that Vida subsequently became very ill. She was sent initially to the Women’s Hospital and then to the Melbourne Hospital, where she died of peritonitis. The Coroner found Elizabeth Downey ‘guilty of the wilful murder of Lilian Vida Helen Patullo’ and committed her for trial. (Age, 4 April 1907, p.6 & 8 April 1907, p.11)

Meanwhile Downey was called to appear in the Carlton Police Court for a committal hearing on the malpractice charge. An initial hearing on 2 May was adjourned, as Mrs Rankin was said to be still too ill to attend. The police were granted an adjournment of one month, but only after bitter criticism from the chairman of the jury, who ‘took strong exception to the actions of the police in the matter’, adding, ‘[t]hey should have had the doctor here.’ (Age, 2 May 1907, p.9) The case resumed on 30 May with Mrs Rankin in attendance. She confirmed that she had visited Mrs Downey and ‘explained to her my object’. Downey named a fee of two guineas for the procedure, although she said that the usual charge was three guineas. As Mrs Rankin was not able to pay two guineas at that point, she was advised to return in one month. This she did, taking her two children with her, and although she still only had one pound, Downey allegedly agreed to treat her. Mrs Rankin returned home afterwards and became very ill. She called in neighbours for help and was treated by a local doctor (Dr Phillips), who also notified the police. The police then took Downey to see Mrs Rankin, who identified her, although Downey continued to protest that she had never seen her before. In response to questioning from Downey’s solicitor Mr Orr, Mrs Rankin confirmed that her husband, who was then in Western Australia, was ‘not responsible for her condition’, although he had sent her the money for the procedure. After hearing evidence from the detectives and Dr Phillips, the magistrate committed the matter to trial in the Supreme Court.

Mid-June 1907 saw Elizabeth Downey back in the Supreme Court before Justice à Beckett defending the charge of wilful murder of Vida Patullo. Her old nemesis Mr Finlayson, QC was prosecuting, while Mr Purves, KC, once again acted in her defence, instructed by Mr E J Corr. The old defence team was back in harness. They would need all their guile to defend their client on this occasion, because detectives had both a dying deposition naming Downey, and a witness in the sister of the deceased. The following story was presented in evidence to the court.

Both Vida and her sister Adeline were apparently employed at the Council Club Hotel when Vida became pregnant. She went first to stay with an aunt in Port Melbourne, but then asked her sister to go with her to Mrs Downey’s house, which they visited on 14 March. Detective Sainsbury later gave evidence that he saw Vida at the house while he was ‘on a visit’ there, although the purpose of his visit was not explained. Vida and Mrs Downey then had a conversation in Adeline’s presence, although Adeline later admitted that ‘she was unable to hear it all,’ and Downey agreed to treat Vida for a fee of £4/10/-. Two days later Vida sent a message asking Adeline to visit her at a house in Pelham Street Carlton, later identified as a house occupied by Mrs Downey’s sister. Adeline found her sister very ill and arranged immediately to transfer her to the Women’s Hospital and then the Melbourne Hospital, where she was diagnosed with peritonitis. While in the hospital Vida gave two statements to police, the second statement sworn before the secretary to the hospital. In her statement, she claimed that she had paid Mrs Downey £4/10/- for a procedure, that ‘something was done to her’, and that she remained in Mrs Downey’s house for about three days before she was moved to Pelham Street. She also stated that no-one else ‘had interfered with her.’ In his evidence the government pathologist, Dr Mollison, testified that ‘death might have been brought about by unlawful means.’

Once again Mr Purves concentrated his defence efforts on questioning the admissibility of the dying deposition, arguing that the first statement was unsworn, while the second was recorded in response to leading questions from the police. The Argus reported his statement in some detail:

If she [Patullo] had been operated upon as alleged she was an accessory before the commission of the crime, and to make the statement acceptable, it had to be corroborated by evidence of equal weight. He could only regard the statement as manufactured evidence. The young woman was asked a series of questions by the experienced Detective Borvett, and the dying depositions were not of the nature of voluntary statements, but represented statements made in answer to suggestions by the detective. It had been shown that the deceased told her sister she had injured herself internally through a fall.

Although Justice à Beckett allowed the statements to be read to the jury, Purves gave notice of his intention to appeal. Under cross-examination Adeline Purves also admitted that she heard ‘only a few words’ of the conversation between her sister and Mrs Downey. In some frustration perhaps, Mr Finlayson’s summary remarks emphasised the importance of taking what he called ‘indirect evidence’ into account: ‘The general circumstances of the case …were unfortunately not uncommon. In most cases of this kind it was absolutely impossible to obtain direct evidence.’ The jury retired at 4.30pm, returning briefly at 5pm to ask if they could give any verdict other than murder. When advised that they could not, they retired again until 10.30pm, but were unable to agree. Once again Elizabeth Downey was remanded for retrial, which took place the following month. (Accounts from reports in Age, 19 June 1907, p. 1 & Argus 19 June 1907, p.4)

At the second trial Mr Purves repeated his objections to the dying statements being admitted as evidence. The newspapers reported the other evidence briefly, but some additional information was included in Elizabeth Downey’s claim that no ‘strangers’ had ‘resided’ in her house during the week in question, a statement supported by both her servant and her daughter-in-law. Perhaps to counter the evidence given by Detective Sainsbury, she did admit to a ‘slight recollection that two girls did come about a position of servant and saw me.’ The jury retired for three-and-a-half hours, before returning a verdict of ‘not guilty’. Once again Mr Finlayson had failed to get a conviction. (Age, 19 July 1907, p.5 & 20 July 1907, p.16; Argus, 20 July 1907, p.21)

But Elizabeth Downey’s legal woes were far from over: there was still the matter of the malpractice charge relating to her treatment of Miriam Rankin. This was heard in the Supreme Court on 19 August before Justice Hodges. By this time Downey seems to have appeared before each of the judges of the Supreme Court – quite a legal feat! The indomitable Mr Purves represented her once again against the charge euphemistically reported as ‘unlawfully us[ing] an instrument for the purpose of procuring a certain result.’ There was some delay while the court deliberated the willingness of Mrs Rankin to give evidence, since in doing so she was likely to incriminate herself in the commission of a crime. However, once the prosecution guaranteed that it would grant her immunity from prosecution, she agreed to testify. No new evidence was reported from this hearing, except that the account of the doctor who treated Mrs Rankin gives some indication of the method employed to achieve the abortion. It seems that an ‘instrument’ was inserted into the cervix and left in place to do its work. It might have been a thin wire instrument, a small catheter or even slippery elm bark, which Janet McCalman notes was often used for this purpose. (Sex & Suffering, p.128) This particular ‘instrument’ was ‘recovered’ by Dr Phillips when he treated Miriam Rankin. Whatever the nature of the implement used, induced abortion in such conditions was an extremely dangerous procedure and likely to have caused the patient intense pain. In searching Mrs Downey’s premises later, detectives reported finding ‘a number of similar instruments’. However, Downey insisted that she used these instruments quite legally ‘in her calling as a ladies’ nurse.’ In a repeat of earlier experiences, the jury in this trial was unable to agree and a retrial was ordered.

The retrial took place on 19 September before Justice à Beckett. This time Mr Finlayson prosecuted, against Mr Purves for the defence. In his summary Justice à Beckett seems to have indicated that he thought the evidence pointed to a guilty verdict, but the jury disagreed and, after deliberating for only one hour, returned a verdict of not guilty. Elizabeth Downey was discharged, after repeated court appearances that once again consumed the better part of a year.

1908 Ruby Aylward

Ruby Aylward died of peritonitis at the Melbourne Hospital on 15 August 1908. She was admitted under the name of Ruby Grey and refused an internal examination, leaving the doctor to conclude that she might be suffering from a perforated gastric ulcer. He decided to operate, and ‘certain conditions were discovered’, although they did not necessarily indicate that an abortion had been performed. At a subsequent post mortem however, evidence of ‘instrumentation’ was revealed. For reasons that were never clarified, the hospital chose not to inform the Coroner and Ruby was literally about to be buried when the coroner’s office was advised that they should investigate. At the subsequent inquest, Ruby’s story turned out to be depressingly familiar.

Ruby Aylward was a nineteen-year-old waitress, who worked in the city. Her only family was an aunt who lived in Kensington. Ruby was engaged to be married to a young man in Sydney but had also been ‘seeing’ another man, identified only as ‘a youth named Potter.’ In late July she confessed to a friend, Lena Benson, that she was pregnant and was miserable because she could not tell her fiancé, while Alf Potter had also gone to Sydney. The Argus reported Benson’s summary of the conversation:

If I am to be married to Tattenall I would not be able to tell him of this, as he would have nothing to do with me. But I know somewhere to go to. I will go to Mrs Downey’s if you will go with me.

Lena agreed to accompany Ruby to see Mrs Downey, who engaged to treat her for a fee of ten guineas. The high price might have reflected the fact, later revealed at trial, that Ruby was then at least four months’ pregnant. Downey also indicated that Ruby would ‘have to come and stay in’.

Lena visited Ruby after the procedure and found her ‘lively’, but when she visited again some days’ later she found her ‘weak.’ Shortly after this Mrs Downey took Ruby in a cab to Spencer Street Station. At the station she met by arrangement with two other women, who took Ruby on to the Melbourne Hospital, where they left her at the gate. This was apparently common practice and was designed to avoid a patient dying in Downey’s care. Downey subsequently advised Lena Benson to say nothing about her visit adding: ‘It would not be nice to be mixed up in these affairs.’

A great deal of contradictory evidence was presented at the coroner’s inquest by members of Downey’s extended family and by her staff, all intending to establish that Ruby was already ill when she came to the house. However, the Coroner disregarded most of this testimony, concluding:

There is no doubt in my mind that this girl Ruby Aylward died from the results of a criminal operation performed upon her by Mrs Downey….I find Elizabeth Downey guilty of the murder of Ruby Aylward.

He committed Downey for trial and set bail at £500 with a similar surety. (Argus, 28 August 1908, pp.4 & 8; Argus 28 August 1908, p.4 & 2 September 1908, p.4.)

The same legal protagonists once again opposed each other in the subsequent trial, which took place in the Supreme Court on 16 December 1908. Little new evidence was presented, but the absence of the doctor who treated Ruby in the hospital cast doubt on the Crown’s case and after a brief retirement, the jury declared a verdict of not guilty. (Age, 17 December 1908, p.9)

Isabel McCallum, 1910

Elizabeth Downey’s long career as an abortionist finally came to an end in 1910, when a young woman, Isabel McCallum, died while still on her premises. Isabel was an unmarried domestic servant living in Geelong, when she became pregnant to her ‘sweetheart’, a blacksmith named James McCarthy. Evidence presented at both the initial inquest and then later at trial, revealed that Isabel tried first to miscarry by taking herbs which she bought from a Mrs Minnie Yee Lee (or Long), the wife of Chinese herbalist Peter Long of Ballarat. McCarthy gave her the money for the medicine. When the herbs did not work, Mrs Lee allegedly advised that an operation was the only recourse. McCarthy told the inquest that he initially opposed the abortion:

I wished to marry the deceased when she told me of her trouble, but she said she would never marry any man until she was well. She then said that she intended to have an operation for a certain purpose performed upon her, and I begged her not to have anything to do with it, but she would not be dissuaded.

His statement was received with extreme scepticism by the court. However McCarthy did provide clear evidence of the careful process in place to convey patients to Elizabeth Downey and to preserve her anonymity. Close contacts and family connections helped to ensure confidentiality.

McCarthy related accompanying Isabel on 4 May to the Geelong station, where they were to have been met by Mrs Lee. When she did not arrive, Isabel asked him to travel with her to an address in Collingwood, where Mrs Lee had alternate premises. At the Collingwood house they were met by Mrs Lee and another, heavily-veiled woman, later identified as Mrs Clara Pennington, Minnie Lee’s sister. Mrs Pennington then took Isabel to Elizabeth Downey’s house, only to find her out. They were forced to return later in the evening. On 7 May McCarthy received a letter from Mrs Lee advising him that ‘Miss McCallum was over her troubles’. He immediately set out for Melbourne in company with a friend but was met on arrival by the news that she had died on the same day (7 May). Mrs Pennington allegedly told him: ‘keep your mouth shut or it will cause a terrible trouble.’ At this point McCarthy’s story suggests that he was more concerned with his finances than the loss of his ‘fiancée’, although that may be unfair. By his own account however he revealed that he saw Isabel’s ‘box’ (case) was ‘practically empty’ and asked for the return of the £10 he had given her for the procedure and of her engagement ring. Mr Pennington said that they would refund £5 ‘when the present trouble was over’, but that he would meet him the following day at the post office to return the ring. This was done. ‘He did, and returned the ring, and told me to swear that I had never seen any of them or had ever been to their place.’

In her evidence to the Coroner Elizabeth Downey claimed that ‘the girl’ (Isabel) came to her house at 11pm on 6 May (rather than 4 May) already very weak:

and as she begged to be allowed to stay was accommodated. On the following morning the girl complained of being ill, and when Dr O’Donnell was called in she was in a low condition and died shortly afterwards while on the way to the Melbourne Hospital.

Government pathologist Dr Mollison then attested that he found death was

due to shock, haemorrhage and peritonitis, the direct result of a criminal operation which had been performed by some unskilled hand. …There were three perforations and considerable force had been exercised.

The Coroner found that Isabel McCallum died as a result of ‘a criminal operation performed upon her by Elizabeth Downey, Clara Pennington and Minnie Long (or Yee Lee)’. He pronounced them all guilty of wilful murder and committed them to trial. (Argus, 16 May 1910, pp. 4 & 8 & 23 May 1910, p.11; Age, 23 May 1910, p.5)

The trial took place in the Supreme Court on 19, 20 and 21 June 1910 before Justice Hood. Mr Woinarski prosecuted for the Crown, while Elizabeth Downey was represented by Mr Maxwell. Her usual defence counsel, Mr Purves, appeared on this occasion for Clara Pennington and Mr Cussen for Minnie Lee. This case was far more perilous for Elizabeth Downey. Not only had Isabel died while still on her premises, but there were other witnesses involved, two of whom had changed their statements before the trial took place. There was also extant correspondence between Minnie Lee and Isabel McCallum, which showed clear intent. These letters, along with the judge’s notes, are preserved in the associated capital case file held by the Public Record Office Victoria.

The correspondence made it clear that Isabel was fearful of the operation, which she obviously knew carried a risk of infection. Minnie Lee reassured her. In a letter dated 15 April 1910 she wrote:

I am glad you wrote yourself as it is you who have to bear everything. You know of cases now and again certainly [presumably of deaths] but they are nothing in comparison with the thousands who get alright. (Mrs Long to Miss McCallum, April 15/10)

In a subsequent note dated 18 April she advised Isabel to ‘make arrangements about going to town as early as convenient as it is better for your own sake’. This was sound advice, as Isabel was by this time some four months pregnant, or more. She had apparently told McCarthy about the pregnancy at ‘about Christmas time.’

Two days later Minnie wrote again to Isabel, explaining how the process would be managed and confirming the costs involved. They were hefty —ten guineas cash for the procedure and Mrs Lee’s costs of 10 shillings plus the fare from Ballarat.

If you could get away about Sat. week I can take you to the place then. I could not stay with you – as only those who are in trouble are allowed there but you will not be alone. I will manage things for you alright. … You will be over it in no time so do not be afraid.’ (Mrs Long to Miss McCallum, 20 April 1910)

Sadly, these were hollow words.

Evidence presented during the trial fleshed out further details. James McCarthy was the first to give evidence. He confirmed that he had approached Mrs Long initially for medicines ‘to bring a girl over her troubles’ after seeing an advertisement in the newspaper. When this was unsuccessful, Mrs Long advised the operation. She reassured him when he expressed his opposition to an operation:

There is nothing to worry about. The girl need not tell her name to the people she is going to. She said something about a little girl who had been there a day or two ago and she had got over her trouble. Mrs Lee told me that thousands of cases had been through her hands and she had never had one failure yet. I asked her would there be any chance of blood poisoning setting in – She said “No, no fear of that as the girl is going into good hands and the woman knew what she was doing and was very clever and also had a doctor behind her back”. (Capital case file)

Given Mrs Downey’s recent history this was either wishful thinking, or clear dissembling on the part of Minnie Lee.

Evidence was also presented by the doctor who attended Isabel at Mrs Downey’s request. They sent initially for Dr Hodgson, but when he was slow to respond tried two other doctors, neither of whom was in. Dr Thomas Hodgson did arrive eventually and found a distressing scene:

I turned down the bed clothes and found a very offensive smell from the bed. …There was a very foul black discharge issuing from the vagina. I found the mouth of the womb very open and I passed an instrument in to see if there was anything inside and removed a large piece of afterbirth of a blue black colour, very offensive and emitting gases of putrefaction. I syringed out the passage and left her. …The cause of her condition was in my opinion that she had a miscarriage. …I told her [Mrs Downey] that the girl was going to die and said do you want her to die in your house or would you rather she died in a hospital. …It is almost invariably the custom to send girls in that condition to a hospital.

Under cross-examination Dr Hodgson confirmed that doctors were reluctant to treat women in these circumstances:

Medical men do not care to have anything to do with cases like this girl’s and that is why they are removed. In my opinion nothing further could have been done for that girl. (Capital case file)

Isabel died about 30 minutes after Dr Hodgson left and before her removal to the hospital could be arranged.

Government pathologist Dr Crawford Mollison performed the post mortem on Isabel and outlined for the court the nature of her injuries. They make uncomfortable reading:

Th injuries on the uterine lip were caused mechanically. The injury to the mouth of the uterus could have been caused by some small instrument being thrust through it, and at the top of the uterus were indications of a wire being thrust through, much smaller than the other instrument and used with considerable force. There were three distinct marks on the outside of the uterus where three distinct attempts, one successful, had been made to push something through. In my opinion the injuries could not have been done by the girl herself. …A small curette used very roughly and unskilfully may have caused the lower injuries but not the upper. (Capital case file)

Both Clara Pennington and Minnie Lee altered their initial statements before the trial. Minnie Long admitted providing medicines, although not to secure miscarriage and denied knowing Mrs Downey. In the end both confirmed that Isabel McCallum had arrived in Melbourne on 4 May. Elizabeth Downey’s two daughters both tried to support their mother’s account of finding Isabel on the doorstep when they arrived home from the theatre on 6 May, but the other evidence was overwhelming. In the end the jury retired for only 45 minutes before returning a verdict of guilty against all three women. In passing sentence Justice Hood remarked that he

thoroughly agreed with that verdict. I draw the conclusion that you have been carrying on this abominable traffic as a regular business. You have been fortunate enough to escape detection until the death of this unhappy girl.

He then pronounced sentence of death against all three women, two of whom collapsed in tears, as did Downey’s daughters, who were also in court. The prisoners were then ‘conducted through the crowd of spectators’ and ‘driven hastily away.’ (Age, 23 June 1910, p.8)

This ended the career of Elizabeth Downey. Once again her defence counsel tried to appeal the decision on the grounds that Justice Hood had wrongly refused his application to have Elizabeth Downey tried separately from the others. He argued that the only real evidence that Isabel was in her house from 4 May came from her co-conspirators and that the decision to try all three women together had prejudiced the case against his client. The appeal was heard by the Full Bench on 12 July but upheld Justice Hood’s decision. Elizabeth Downey had reached the end of the legal road. (Age,13 July 1910, p.14)

As usual before the sentences were considered by the Executive Council the police were asked to provide reports on all three prisoners. Given free rein to comment, they did not hold back on Elizabeth Downey.

We have the honor [sic] to report for your information that the prisoner Elizabeth Downey 57 years of age, has posed as a nurse in Carlton and North Melbourne for some 18 years, but for the greater period of that time has been looked upon as a professional abortionist. …[summary of her many previous charges]

Besides the cases named, numerous deaths have occurred in the public hospital during the past few years from criminal abortions, in which arrests have not been made, generally through the patient secrecy, but in many of them, evidence of complicity against the prisoner has been obtained but not sufficient to justify action being taken against her. For the last three or four years she has been drinking freely and it is the opinion of those who know her that that has something to do with her unskilled criminal work of late years.

Notwithstanding it has cost her upwards of £2000 during the past ten years in defending herself on criminal charges (this we have on good authority) she has purchased valuable land, a farm at Bunyip, and the whole of this money is the result of her abominable traffic.

She has a husband, a big worthless fellow, who sometimes goes up on the farm, but is principally about the City. She has also two married daughters, and a son, all a worthless lot.

To sum up this woman’s character we could give no better definition that that she is a notorious criminal abortionist, and when the occasion arises, as in the present case when trying to conceal her guilt, one of the most callous type.

Arthur Det &

Napthine, Det. (Capital case file)

Ouch! Revenge at last perhaps! The comment about her drinking is an interesting one and may help to explain the number of botched procedures that led to the spate of prosecutions in the past few years, but a comment by one of her daughters at her last trial also suggested that she had been treated in the past year for a ‘paralytic stroke’. If that was the case, she might well have been left with a tremor in her hands, which might explain the several ‘unskilled’ attempts to insert the fatal wire or other instrument in Isabel. Either way it increased the risk to her unsuspecting patients exponentially.

By contrast, the report submitted on Minnie Long by a police sergeant in Ballarat was far more positive.

Minnie Long has always been looked upon in Ballarat as a respectable woman, in fact there is nothing against her character up to the time of her present trouble. The Ballarat East Police speak well of Mrs Long. She is said to be of a kindly disposition towards poor people. I have known Minnie Long and her husband for some years, that is since they came to reside in Ballarat East, and I can only speak highly of them. I have not at any time heard it suggested that any illegal business was being carried out by them. I am inclined to the opinion that this has only been going on since Minnie has opened the branch of the business at her sister Mrs Pennington’s house some 3 months ago. Mrs Long has a lovely home at Will Street Ballarat East, and it is kept very clean and tidy which shows me that she was a good wife. Since Minnie Long was arrested by Detective Arthur and myself…I have not heard a single word against her character; one and all appear sorry to see her placed in the position she is.

Rogerson,

Sergt.

A verdict of guilty on a murder charge at this time carried an automatic death sentence, but in practice all sentences were then considered by the Governor, as advised by Cabinet (known as the Executive Council of government). This met then and still meets now, in the Old Treasury Building. At its meeting in late July the Governor in Council decided to remit all sentences to terms of imprisonment. There was a strong movement against the death sentence in Victoria during these decades, but there was especial public opposition to the execution of women. In this context it was not surprising that the Governor agreed to commute the sentences. Elizabeth Downey was sentenced to imprisonment, effectively for the term of her natural life. Technically the recommendation read ‘imprisonment for life with hard labour, without the benefit of the Regulations relating to remission of sentences’. Minnie Long’s sentence was set at 15 years, despite the favourable police report, while Clara Pennington was sentenced to 10 years. All were confined in Pentridge Prison. (Capital case file, Executive Council Memorandum for His Excellency the Governor, 26 July 1910.)

In fact Elizabeth Downey would serve less than two years before she suffered a major stroke in prison. The prison allowed her family to stay in the infirmary with her and she died on 23 April 1912. Once again reports of her age varied between 63 years and ‘about 70 years.’ It seems however that the police assessment of her financial status was reasonably accurate, since on 5 July 1912 the Age published the following notice in its wills and estates column:

Isabella Allinson, sometimes known as Elizabeth or Isabella Downey, late of Connell-street North Melbourne, nurse, left by will dated 20/7/1910 real estate valued at £2360 and personal at £958 to her children. (p.7)

Clearly there was a profitable living to be made from performing illegal abortions for those prepared to take the risk.

How should we view the activities of abortionists like Elizabeth Downey? Of course, official comment at the time condemned their actions in the strongest terms, echoing the remarks of Justice Hood and the police. Editorials in the major newspapers were equally damning. The Age called it a ‘heinous’ crime, but still went on to recommend mercy, while there were other signs that public opinion was moving away from unquestioning acceptance of society’s double moral standard. The Age published a lengthy editorial on the case on 15 July:

Our opinion is fortified by the fact that behind the three convicted murderesses stands a more atrocious moral criminal — a man, who by virtue of certain unspeakable defects in our social and legal systems, has been permitted to escape absolutely unpunished. That man is the seducer of the miserable girl who paid away her life as the price of attempting to conceal her shame with the aid of the abortionists. The man was primarily responsible for the girl‘s ruin. He sacrificed her soul and body to his lawless passion; then, when she wished to avoid the natural consequences of her weakness, he scouted honor, turned his back upon his duty, and callously suffered her to destroy and be destroyed. We declare with deep conviction that this man far more richly merits capital punishment than the three wretched women who lent themselves as the unconfessed tools and servants of his wickedness. Surely it is time that the public opinion of Victoria should direct its energies towards an enlightened readjustment of the ill-balanced burdens of the sexes. (Age,15 July 1910, p.6)

There was a great deal more in similar terms. Those who wish to read it in full can find it here.

Others had expressed similar views when considering the many desperately sad cases of young women appearing before the courts charged with the crime of child murder, or the lesser charge of concealment of birth. See, in particular, public comment on the case of Maggie Heffernan in 1900. In 1900 the Victorian Government had responded to consistent lobbying from feminist Vida Goldstein, amongst others, to introduce legislation to compel the fathers of illegitimate children to provide financial support. It would, however, prove notoriously difficult to enforce and it was not until the federal government finally extended access to the pension to single mothers in 1973 that it became possible for women to maintain their children in a semblance of decency.

But economic support was never the only issue. Until well into the 1970s the shame of an unwed pregnancy was often the paramount consideration of young women seeking an abortion. To those women, abortionists like Mrs Downey may have appeared more in the guise of a saviour than a potential criminal. Certainly, most of those treated by her and by others refused at first to identify those responsible for their injuries, even when they knew that death was imminent. Despite the legal risks, wealthy women could almost certainly access relatively safe abortion at this time, performed in one of the several private clinics that provided a discreet service. Most procedures were described as routine dilation and curettes. Janet McCalman suggests that some of the doctors from the Melbourne Hospital probably provided this service, but the fees were well beyond the means of most working women. It was not until 1969 that the laws banning abortion were repealed and access to legal, safe abortion finally put the back-yard abortionist out of business.