Phrenologists believed that a person's intellect and personality could be predicted by studying the shape of his or her head. The ‘science’ of phrenology was hugely popular in the nineteenth century, with lectures attracting large crowds in Melbourne. It was even recommended to help in the choice of a wife: ‘One of the first requisites… is to ascertain that she has a good head.’

Reading the skull

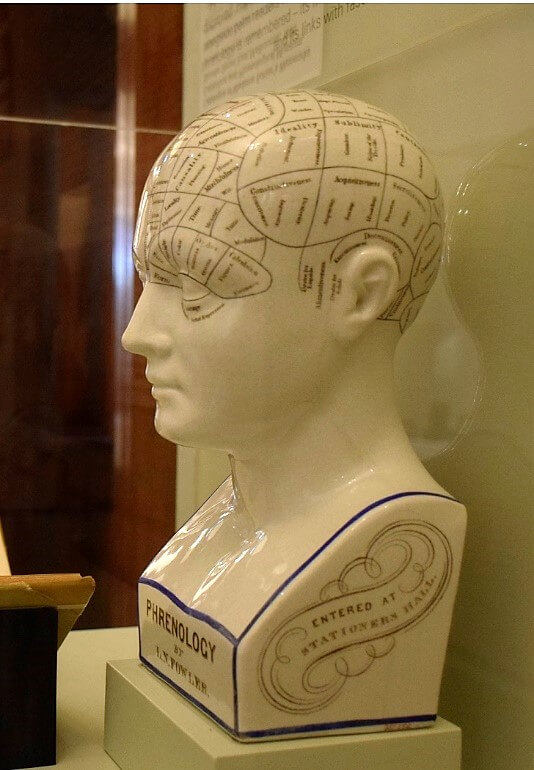

Phrenologists would ‘read’ a patient’s head by running their fingertips and palms over the skull. Bumps or depressions suggested aspects of personality and attributes, both positive and negative — love of one’s children, carnivorous or murderous instincts, poetic talent, circumspection or religiosity. A protruding forehead, for example, was thought to indicate an impressive intellect: a bump on the crown was a sign of morality.

Phrenological busts were created as reference guides for use when reading a subject’s skull. An entire series of 39 casts comprising the ‘skulls of different nations’ cost about 3 pounds.

The ‘criminal type’

Phrenologists were fascinated by the skulls of criminals, linking skull structure and morphology to flawed character, or a ‘criminal type’. In 1880 phrenologist A.S. Hamilton examined the death mask of bushranger, Ned Kelly. A death mask is a cast of a person’s head created after death. He identified ‘dangerously-overdeveloped’ cranial regions, indicating ’combativeness’ and ‘destructiveness’, and warned that heads of Kelly’s shape were a danger to society: ‘there are few heads amongst the worst that would risk so much for the love of power…’

A lost (pseudo) science

By the late-nineteenth century the scientific basis of phrenology had been disproved. Popular phrenologists retreated to arcades and markets to practice alongside palm readers and fortune-tellers. Today mostly the darker history of phrenology is remembered –— its misuse to create racial and sexual stereotypes and its links with fascist ideology.

On display in Lost Jobs is this phrenological bust, on loan from the Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences. It provided a three-dimensional reference guide to assist the reading of a subject’s skull. The bust was made in the 1850s by Lorenzo Fowler, a leading exponent of phrenology

Lorenzo Fowler and his brother, Orson, lectured throughout Britain in the 1860s, establishing several phrenological institutions and societies. Mark Twain wrote about visiting Lorenzo Fowler in London in 1873:

I found Fowler on duty amidst the impressive symbols of his trade. On brackets, on tables . . . all about the room, stood marble-white busts, hairless, every inch of the skull occupied by a shallow bump, and every bump labelled with its imposing name, in black letters.

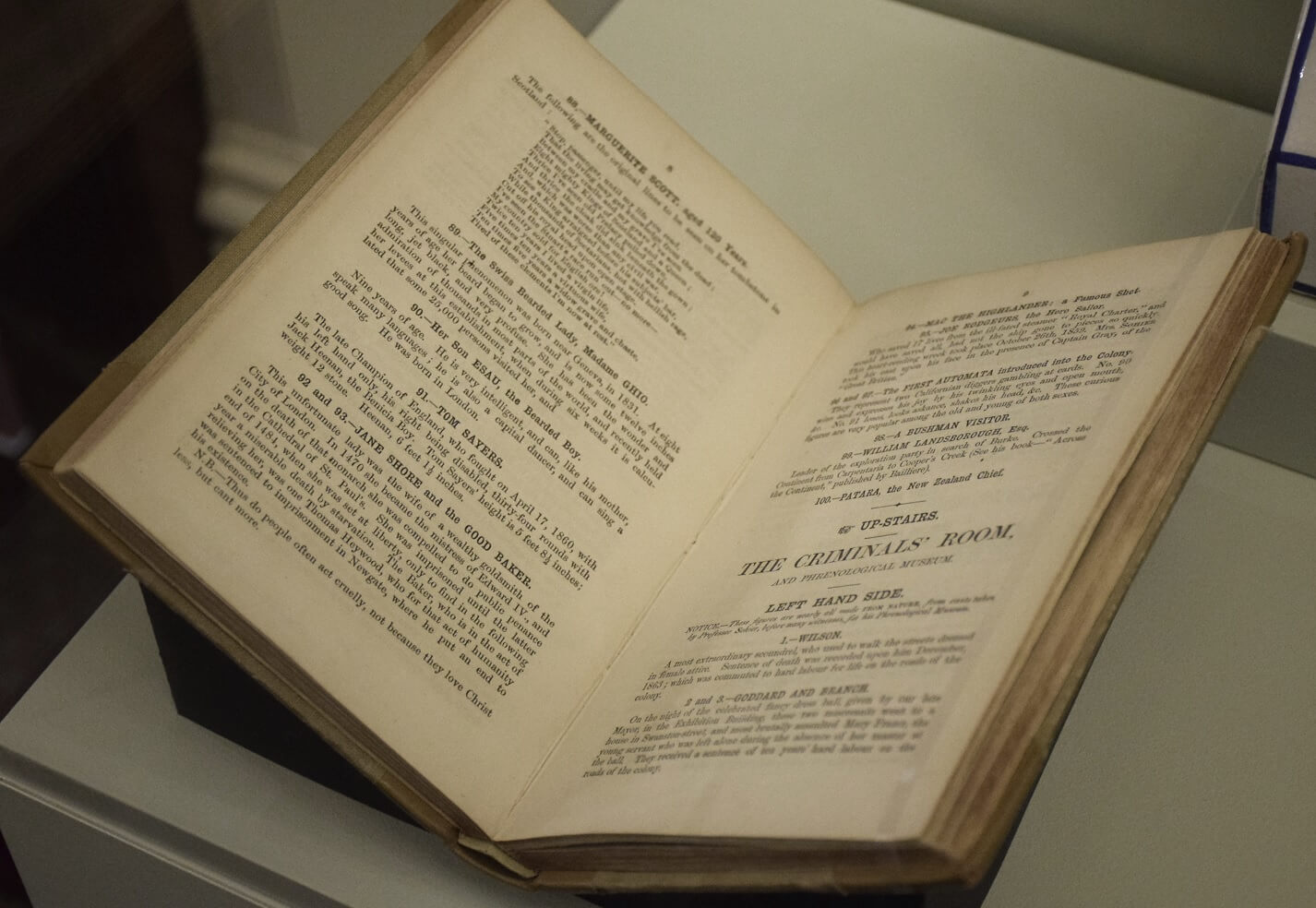

Catalogue of Madame Sohier’s Waxworks Exhibition and Phrenological Museum, Bourke Street East, Melbourne, 1865

Courtesy State Library Victoria

Another item on display in Lost Jobs is the 1865 catalogue of Madame Sohier’s Waxworks Exhibition and Phrenological Museum, which was located in Bourke Street East. It is on loan from State Library Victoria.

Melbourne’s Waxworks and ‘Phrenological Museum’ was owned by Mrs Williams and Philemon Sohier, Melbourne’s leading phrenologist. The Museum was a major attraction in early Melbourne with annual visitor numbers of over 100,000. Highlights included the Chamber of Horrors — a gruesome array of wax murderers, modelled from their death masks. Sohier consulted at the Museum, with phrenological readings for 10 shillings and a ‘register of the brain’ for 6 pence.