In addition to wool, another major focus of agriculture in the nineteenth century was the cultivation of wheat and other cereals. At first it was cheaper to import food than to grow it and the acreage under crop was small. But as the population expanded and prices rose, the Government began to sell land for farming near Melbourne. By 1841 more than 8,000 acres were under cultivation, mostly along the waterways near Melbourne and around the Plenty River, and by 1844 the Port Phillip District could supply 70 per cent of its wheat needs.

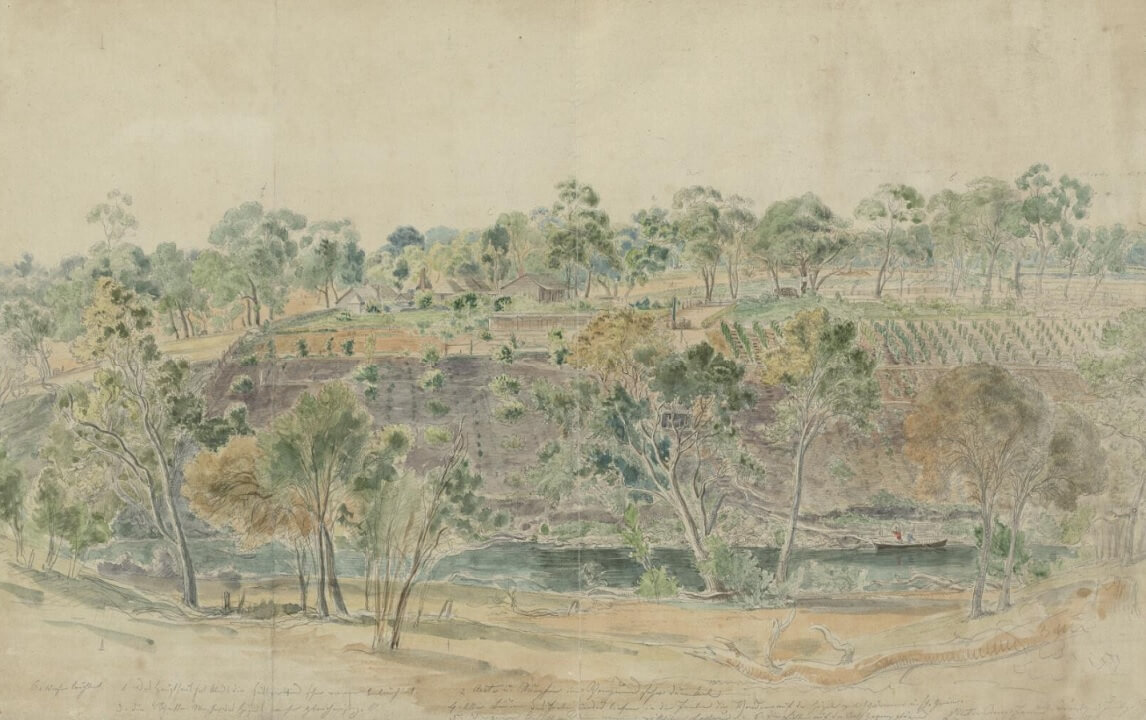

Mister Berry’s [Perry’s] farm, Melbourne, Eugene von Guérard, watercolour, 1855

Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia

This small farm is clearly taking advantage of the well-watered plains along the Yarra. Some of the land may have been cleared for cereal cropping, with vines or perhaps fruit trees on the upper field.

Agriculture stagnated in the first years after gold was discovered, as men rushed to the gold fields and the cost of labour skyrocketed, but it began to expand again after 1854. By 1861 there were nearly 440,000 acres under crop in Victoria. Wheat accounted for 196,000 acres, while other cereal crops and market gardens, orchards and vineyards made up the rest. By 1861 some 35,000 men were employed on farms, while agriculture expanded steadily inland towards central Victoria. The 1870s was a major period of expansion. In 1871 there were 937,000 acres under cultivation, increasing over the next decade to 1.8 million acres. Farmers were assisted by the Selection Acts, which helped to break up the large pastoral runs, freeing land for other farming uses. The introduction of protective tariffs and an expanding railway network were also important. Wheat was the largest crop grown. By 1877 Victoria was self-sufficient in wheat and began to export its surplus. With South Australia, Victoria produced four-fifths of Australia’s wheat crop in the 1870s and eighties. Hay and fodder were also important in this time of horse-power.

Work on the farm

Agriculture was far more labour intensive than pastoralism and in the 1870s and eighties farmers and farm labour comprised one-quarter of the male workforce. Labour was required at every stage, from planting to harvest, but especially at harvest time, when large numbers of men might be needed to cut a crop in time. In the absence of machinery, farmers were dependent on horse-power and man-power. Fields were first ploughed, sometimes several times, using either wooden or steel ploughs and as many horses as a farmer had at his disposal. At the end of a long day, the farmer still had to tend his horses, before seeking his own dinner and rest. Large farms might harness eight horses to a plough, but one, two or four-horse teams were common, while some poor farmers pulled the plough themselves. State Library Victoria has one photograph showing Chinese farmers ploughing near Kiandra in the late-nineteenth century (below). One man is hitched to the plough, while another guides the blade and a third follows behind, perhaps planting potatoes in the furrow. It was desperately hard work.

Chinese farmers ploughing and planting near Kiandra, c. 1880s

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

Four horse team ploughing a field, c. 1900-1920

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

Eight horse team ploughing in Woomelang, 1920. Thomas Gale photographer.

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

Harvesting the crop was equally labour-intensive. Until mid-century and beyond in some cases, crops were cut by hand by men wielding long-handled scythes. Very small plots might be cut by sickle, but that involved far too much bending to be feasible for larger paddocks.

Scythe, early 20th century

Old Treasury Building Melbourne collection

Hand sickle, late 19th century

Courtesy private collection

Both scythes and sickles had been used since Medieval times. From the mid-nineteenth century they were replaced gradually by horse-drawn strippers or mowers, then by the combine-harvester. The long-handled scythe was used with a long, sweeping movement, using both hands. Often men would work in rows, spaced apart and moving in rhythm across a cereal field. An experienced man could cut an acre of cereal in a day. By contrast a modern combine-harvester can harvest between 150 and 200 acres of wheat per day.

Rochester, 1948

Gelatin silver print. J W Moore photographer

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

Scythes and sickles continued to be used into the twentieth century. In this photograph three men are shown using long-handled sickles to cut cumbungi (rushes, or sedge) near water channels in Rochester. They were identified as Mr. McMillan, Mr. W. Sindridge and Mr. J. Reid.

When harvesting grains other workers followed behind the men with scythes, to gather the cut cereal stalks into bundles or sheaves, which were tied loosely with the straw. Several sheaves were then propped up in stooks to dry in the sun. In Britain and Europe gleaners, usually women and children, came onto the fields at the end of the day to pick up any grain that had been missed. Whether this also happened in Australia is not clear.

Once the grain was dry, the stooks were taken to be threshed, to separate the grain from the stalks. Threshing was done with a flail, which was a long-handled tool with a heavy wooden club attached. The thresher hit the grain heads to break the grain apart. A strong man could thresh about seven bushels of wheat (190 kilos) per day. After threshing, the straw was raked away to be used for animals, or for bedding, and the remaining grain heads were winnowed. Winnowing used the wind to separate the lighter chaff (husk) from the heavier grain. Once this was done, the grain was bagged for use or sale. It was a long, arduous process. Not surprisingly, the invention of machinery that could speed up the process, was welcomed by farmers.

Vite Vite North, Victoria, circa 1925

Reproduced courtesy Museums Victoria

Threshing grain by hand. This photograph shows a stationery engine in use, perhaps operating a mechanical chaff cutter.

Machinery on the farm

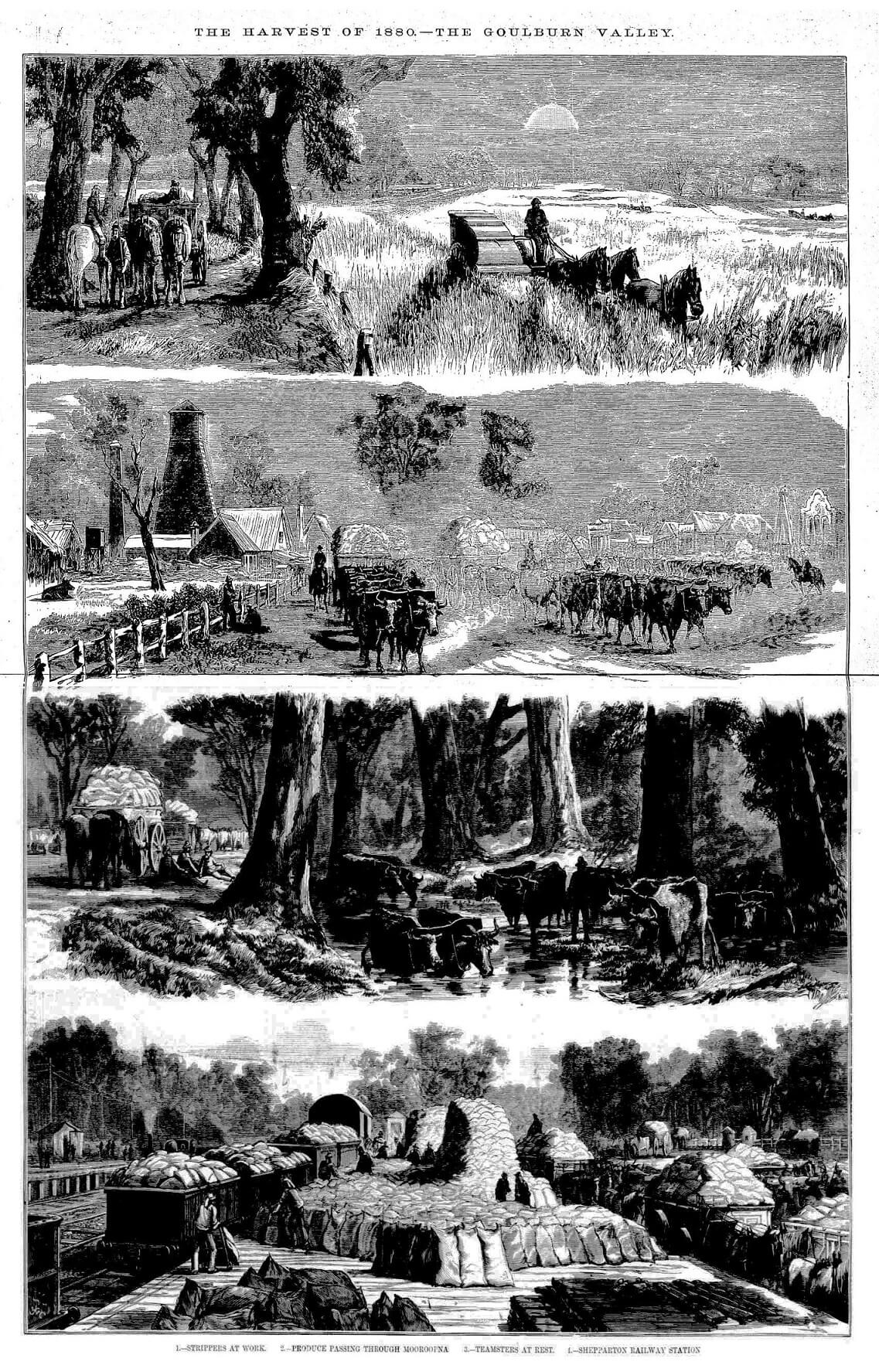

The Harvest of 1880 — The Goulburn Valley

Wood engraving, James Waltham Curtis in The Illustrated Australian News, 16 February 1880

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

Farming machinery was expensive, but it replaced the labour of many men.

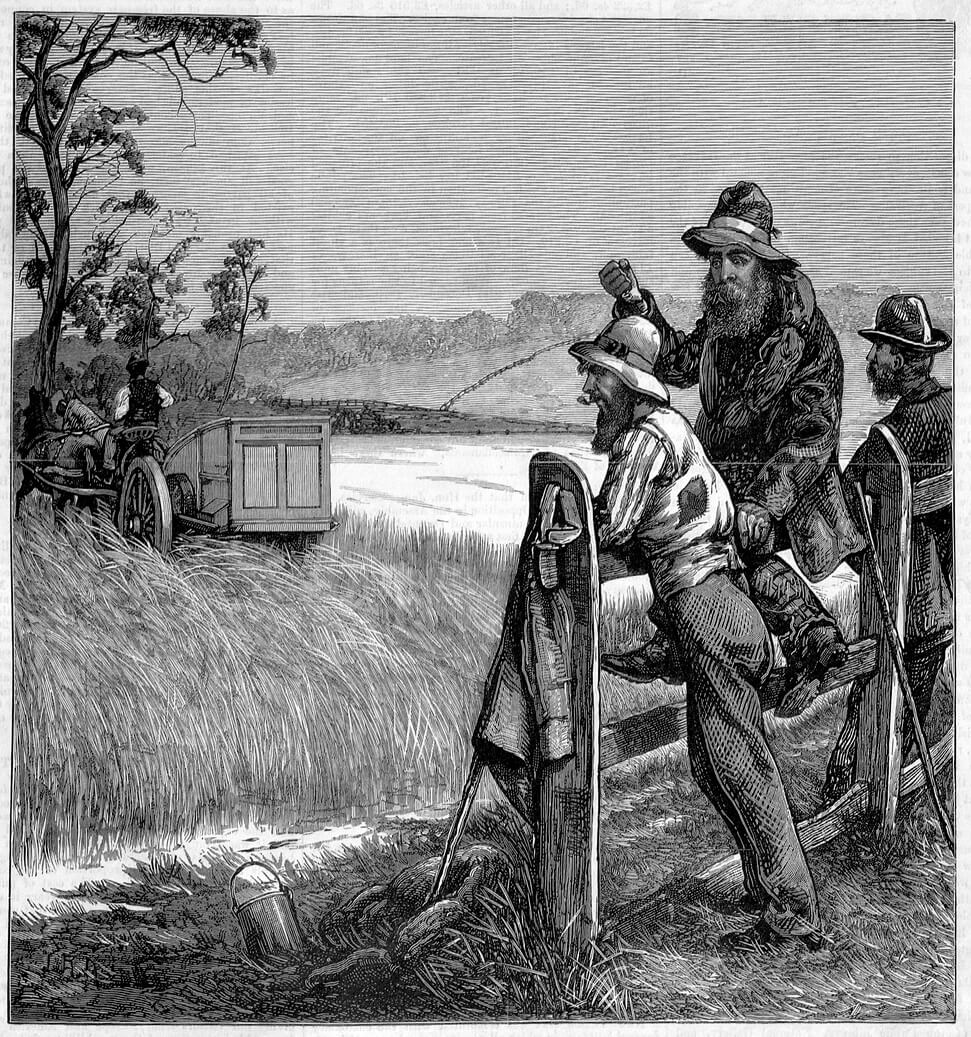

Harvest in Victoria: The Farmer’s New Harvest Hand

Wood engraving, Julian Rossi Ashton, in The Australasian Sketcher, 15 January 1881

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

In this image published in 1881, the artist Julian Rossi Ashton showed three itinerant farm workers watching at the farm gate as the crop they might have harvested is reaped by a machine. At this stage men were still required to rake the hay or straw after cutting and set it into stooks, but in time this too would be done by machine. Sunshine’s famous combine-harvester could harvest, thresh and winnow a grain crop.

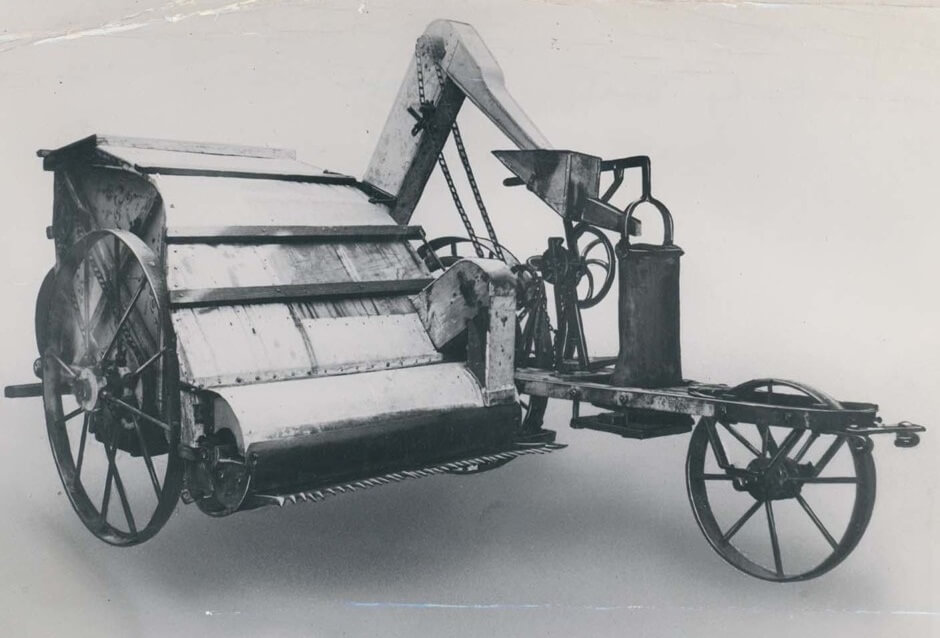

Sunshine Stripper Harvester, c. 1886

Reproduced courtesy Museums Victoria

Hugh Victor McKay built his prototype stripper harvester at the age of 18 on his father’s property at Drummarton. He sold several to farmers in Victoria and New South

Wales in 1885-6. McKay was not the first to design a ‘combine harvester’, but clever marketing saw his ‘Sunshine’ harvester become the most popular design by 1900. His agricultural machinery works moved from Ballarat to Sunshine, north of Melbourne in 1906. Eventually it would become one of the largest machinery works in Victoria, employing thousands of workers.

Harvester at work, 1911. Glass plate negative

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

Bagging the wheat, 1911. Glass plate negative

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

This harvester allowed the farmer to bag wheat on the spot. The bags were made of hessian (jute) and were hand-sewn closed on the farm at the end of a day’s harvesting.

Transporting the crop

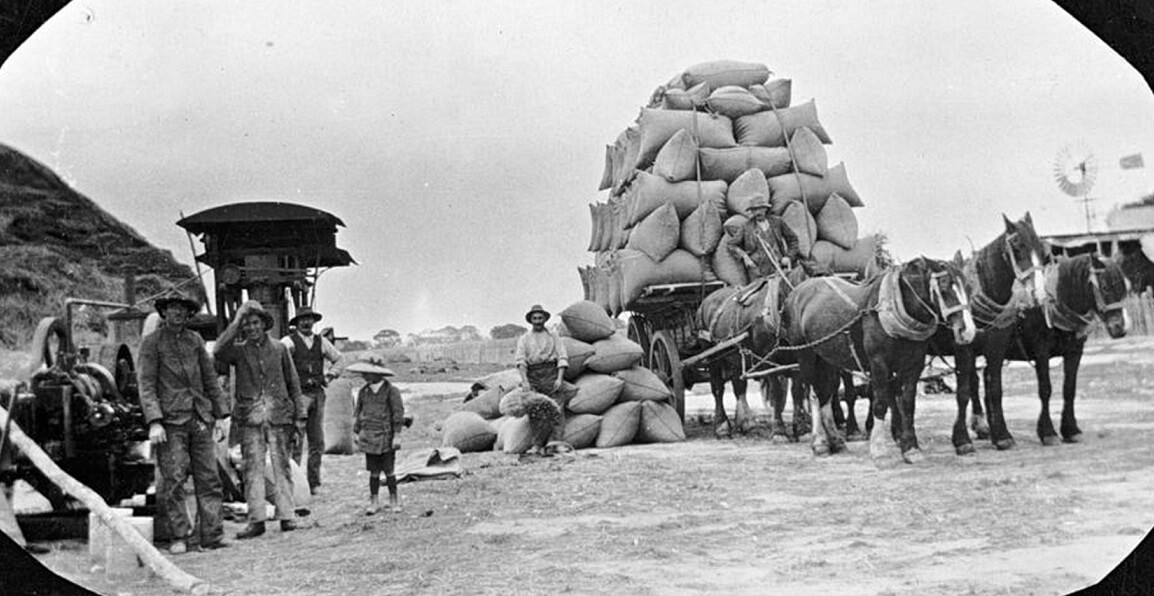

Once bagged on the farm, wheat was transported to the point of sale. In the first decades bagged wheat was often carted by bullock wagon and bullocks continued to be used for this heavy work into the twentieth century. The alternative was a team of work horses, hitched to a wagon. From the mid-nineteenth century, as rail lines spread across the Colony, wagon loads were increasingly delivered to a railway siding for loading on to rail cars.

Wheat Carting Bullocks, Sheep Hills, c. 1945-54

Victorian Railways Collection

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

This photograph shows a huge team of 12 bullocks hauling a wagon loaded with wheat bags at a railway siding.

Gillett Family With Chaff Cutter & Horse Team, Leigh District, Victoria, circa 1920

Reproduced courtesy Museums Victoria

Wheat stack, Minyip, c. 1945-54

Victorian Railways Collection

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

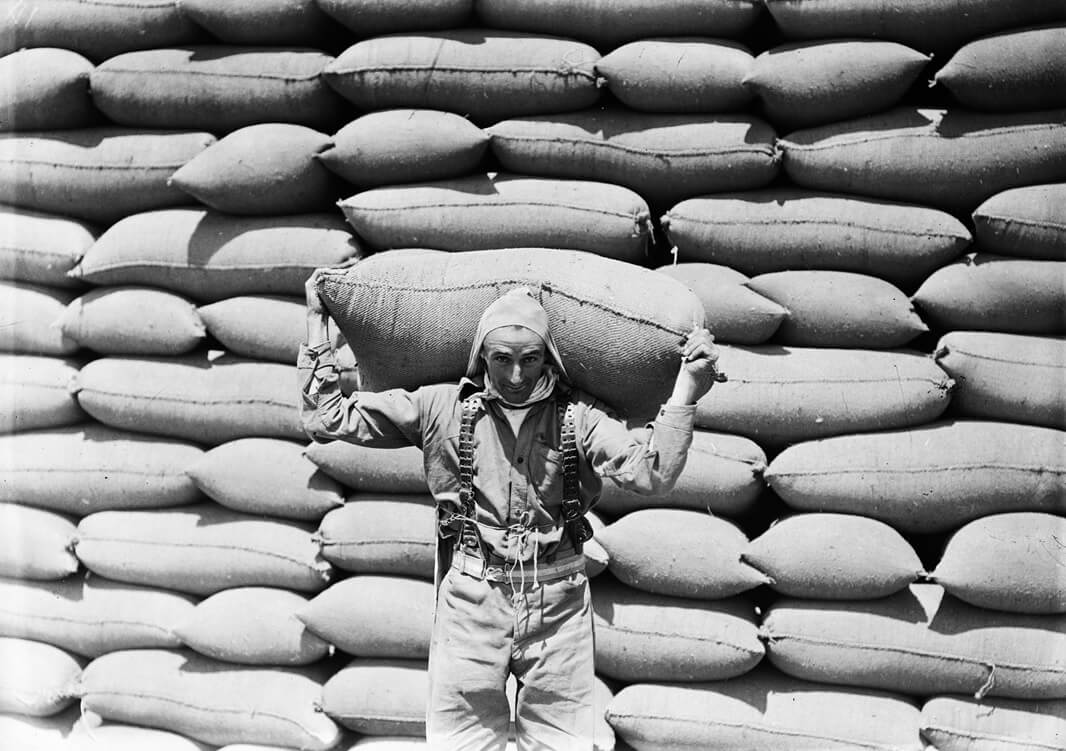

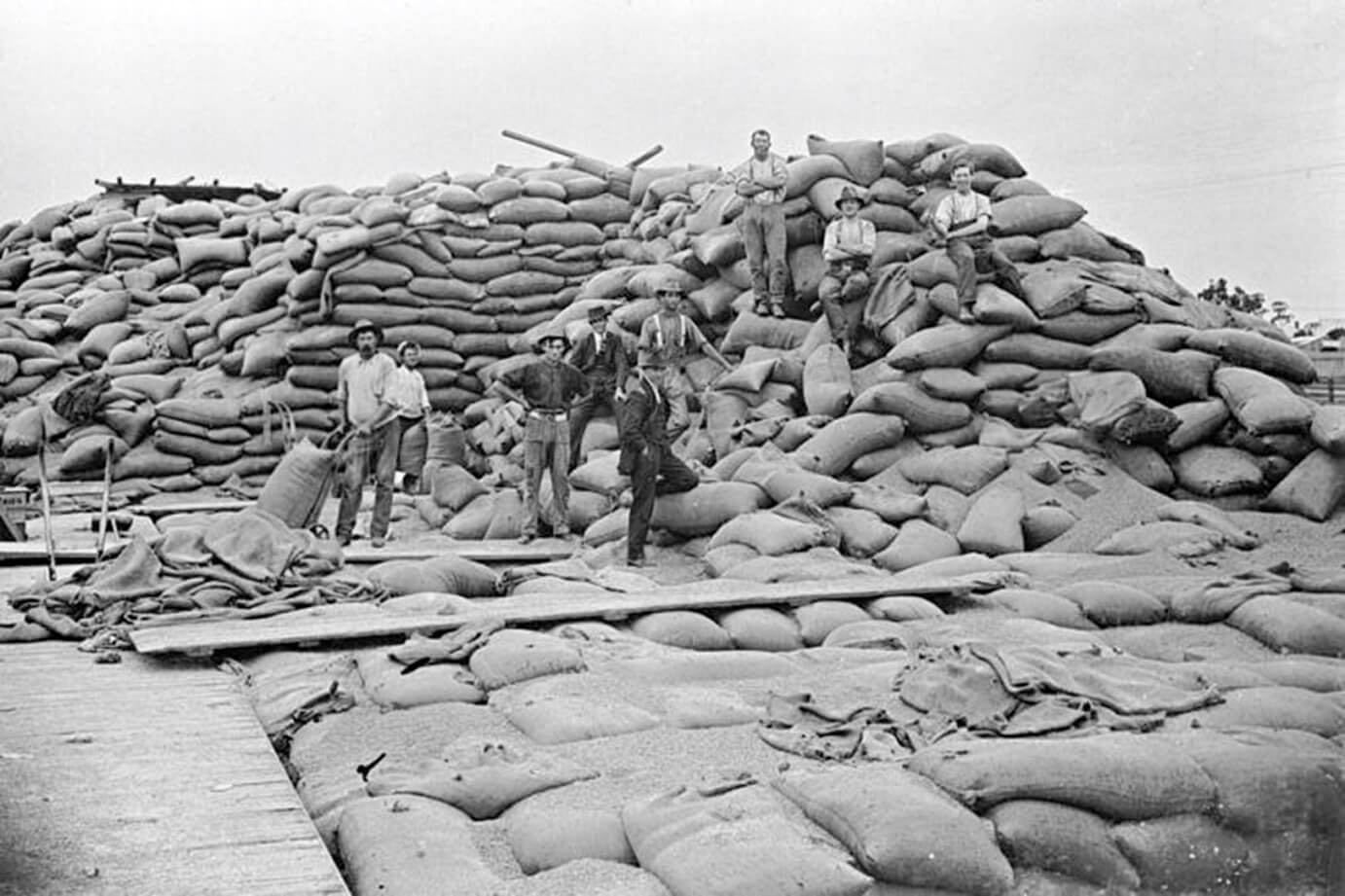

Once at the rail sidings, the wheat was piled into giant wheat stacks. It was heavy work loading and unloading wheat bags, which commonly weighed about 60 kilograms. At railway sidings this work was often performed by wheat humpers, who balanced the heavy sacks across their shoulders. On the wharves, the same task was generally performed by a ‘lumper’.

Storing the grain

Wheat stacks were susceptible to a range of problems, from the weather to pests. Mice were a particular problem and reached plague proportions in some years. Mice could wreak havoc on stored grain and could ruin a harvest with heart-breaking speed.

Workers on Ruined Wheat Stack, Warracknabeal, Victoria, 1917

Reproduced courtesy Museums Victoria

Men working on a wheat stack damaged by a mouse plague. They are moving bags with trolleys. The stack was in the Warracknabeal rail yards.

Wheat stack with mouse guards, Underbool Railway Station yard, c. 1925

Reproduced courtesy Museums Victoria

Attempts to put mouse guards around the base of wheat stacks were partially successful.

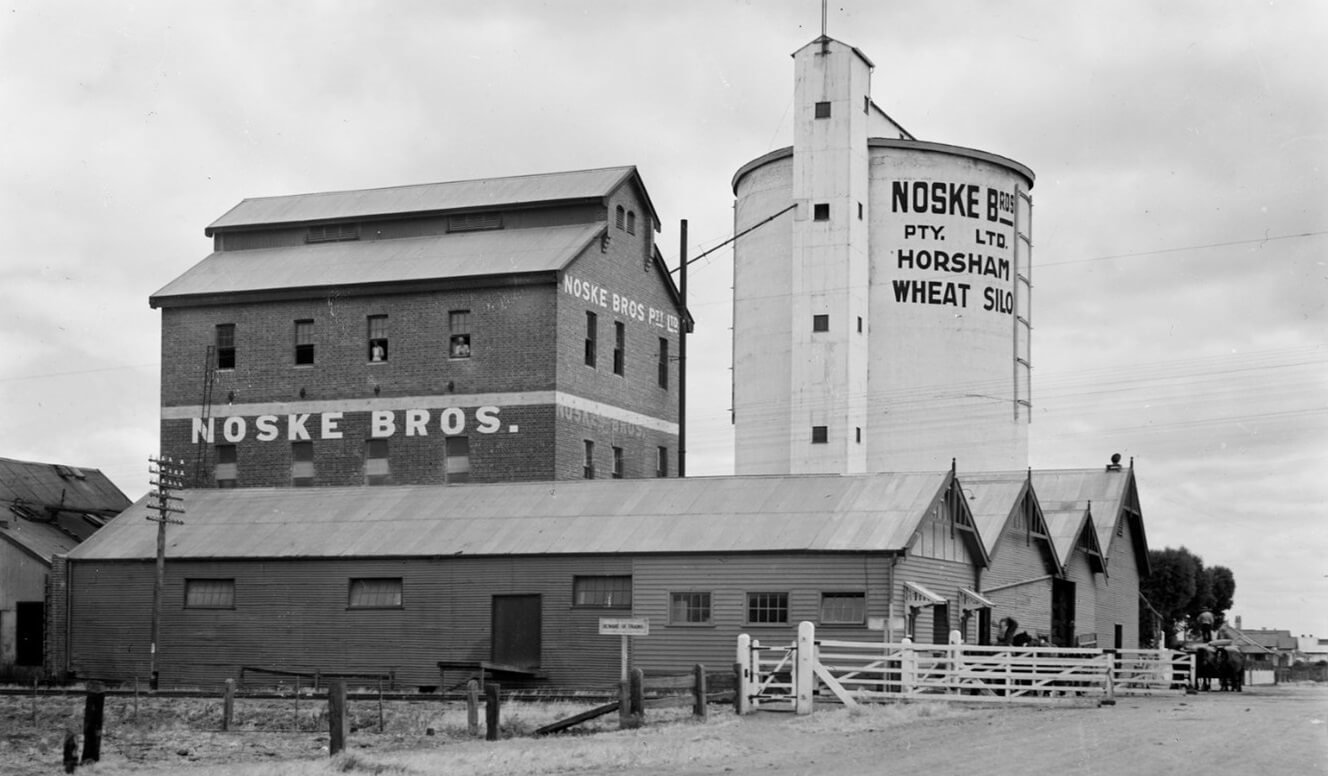

Bulk storage and handling

In an attempt to lessen the damage to grain harvests, inventors devised sealed silos to store the grain in bulk. ‘Bulk-handling’ was introduced progressively from the 1930s and revolutionised the transportation and storage of grain. It also made the wheat humpers redundant. In time smaller grain silos were made for on-farm storage.

Opening of Geelong wheat silos and wharf loading equipment, 1939

Reproduced courtesy Public Record Office Victoria

The silos and conveyor belt were built by the Victorian Government.

Noske Bros, Wheat Silo, Horsham, Vic. C. 1940-54

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

Building the Rochester silo, 1942-9

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

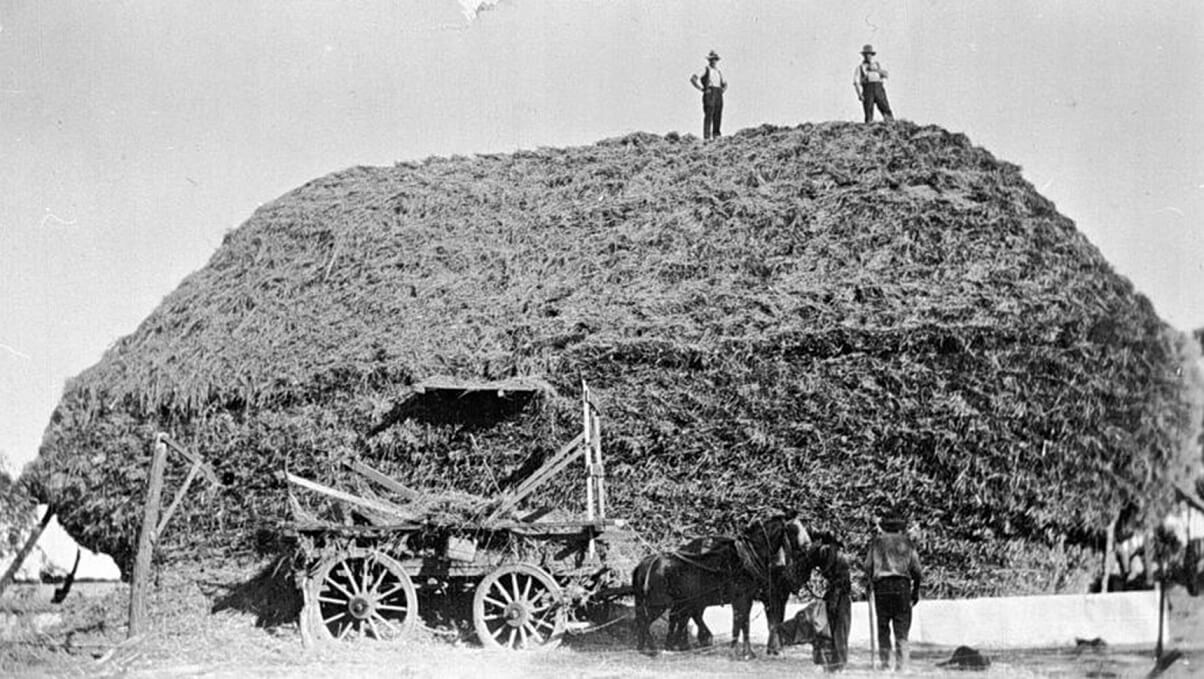

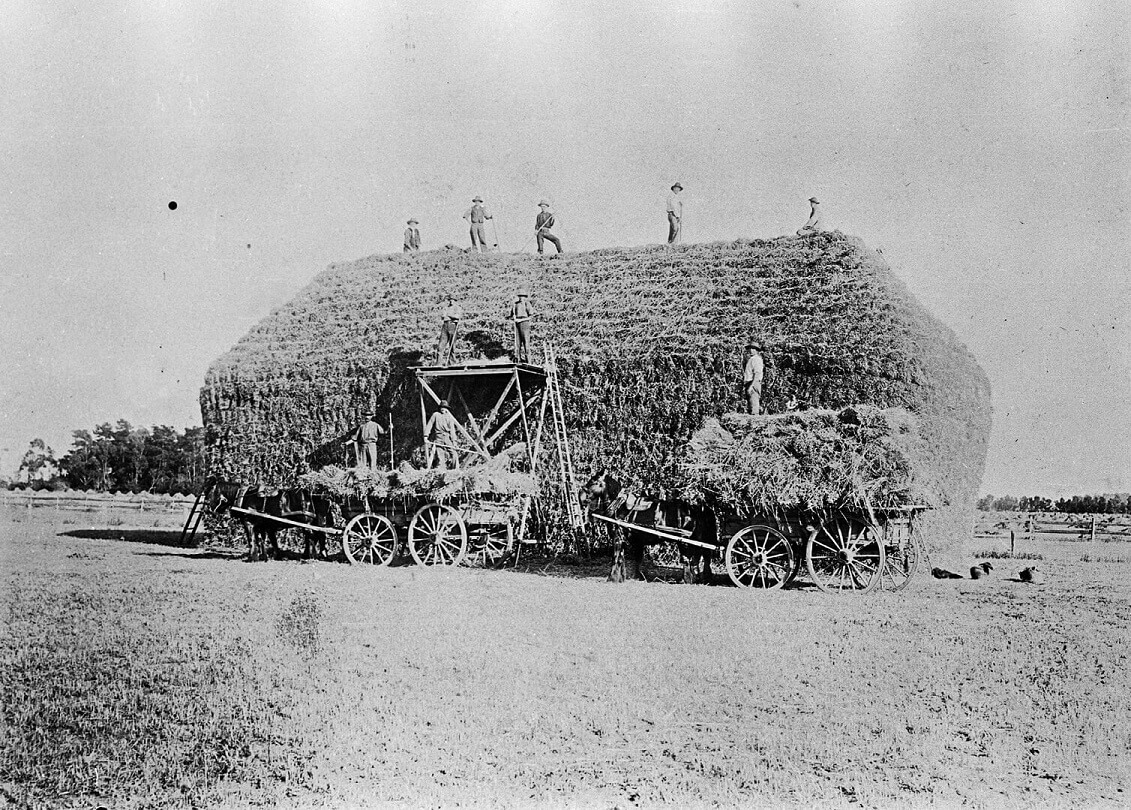

Haymaking

Hay was cut in much the same way as grain, but before the grain matured. It was left to dry on the ground and then turned several times to ensure that it did not mould, before being gathered into bundles, stooks and finally haystacks. Nineteenth-century haystacks could reach mammoth proportions, all built by hand with pitchforks. There was an art to building a haystack that was both stable and waterproof, but some of the stacks were so tall that working on top of them must have been very dangerous. There is a heroic quality to some of the photographs of men building haystacks.

Glengower, Victoria, 1939

Reproduced courtesy Museums Victoria

The horses provide a rough sense of scale to this haystack. Falling off would have caused serious injury. But how did the men get down?

Men building a haystack Werribee, 1910

Reproduced courtesy Museums Victoria

These men at least had a scaffold and a ladder to help them. Eight men can be seen in the photograph building the stack.

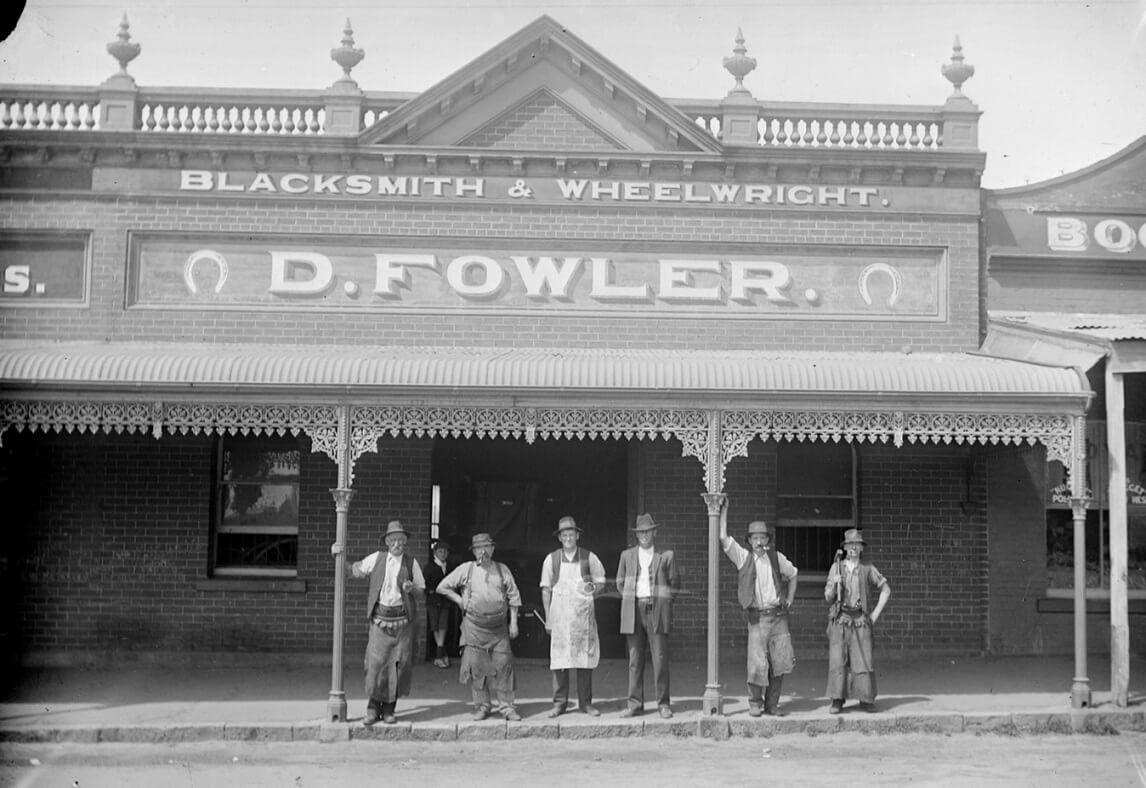

Mechanisation

Mechanisation of agriculture gathered pace in the twentieth century. Combine harvesters were joined by a host of other specialised machinery designed to replace the need for manual labour. Tractors were a huge boon to the farmer and soon were used for everything from ploughing to harvest, although the horse was still used well into the 1950s on some farms. With the demise of horse-power, other rural trades declined too. Blacksmiths were once ubiquitous in regional towns, but the craft is now classed as a ‘rare trade’.

Mr H. Hinge’s blacksmith shop, Bendigo Victoria, 5 September 1853, C J W Russell

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

Blacksmiths were essential to both urban and rural life until well into the twentieth century. This makeshift tent/shop was erected on the Bendigo gold field in 1853. It probably provided Mr Hinge with a more reliable income than gold seeking!

Fowler, Blacksmith & Wheelwright, Ararat, c. 1890

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

By the late-nineteenth century, some blacksmiths’ premises were quite superior, although the work remained much the same — hot, hard and dirty.