Milch cows arrived in the first years after 1835 to supply milk, butter and cheese. At first most was for family use, but as the number of dairy cows grew, attempts were made to build a butter and cheese-making industry. By 1881 there were over 300,000 milch cows in the Colony, with most concentrated in Gippsland, areas of the Western Districts and near Melbourne. Dairying faced many obstacles in the period before refrigeration transformed the industry. It was especially labour-intensive. Even experienced hand-milkers could usually only manage to milk four to six cows per hour and that was just the start.

To make butter, the milk was first poured into shallow pans and left for the cream to settle on top. The cream was then skimmed off (again by hand), placed in a churn and hand-churned. Depending on the quantity of butter fat and the temperature of the day, that might take at least half an hour. Butter makers were usually advised to make butter early in the morning when it was cooler and to try to keep the cream as cold as possible. The clumps of butter were then worked to squeeze out the whey, and the butter salted and shaped. The amount of salt used depended in part on the distance the butter had to travel. In Summer this could not be far, for obvious reasons! Since milk was unsterilized, the interval between butter production and sale to the customer had to be as short as possible. Early milking sheds were insanitary places, with earthen floors, soon contaminated with cow dung. Milk containing high levels of bacteria was prone to sour quickly, especially when it could not be kept cold. On some farms milk and cream was stored in the local creek to keep it cool, but this was only a short-term measure. It was estimated that only about one third of the butter made on farms reached the market in a quality suitable for consumption. The rest was sold cheaply to confectioners or soap makers.

Seasonal variations

Milk production was also variable. In winter, when the grass was dormant and many cows were in calf, milk supply dwindled and both milk and butter could command high prices. The reverse was true in Spring and Summer, when a glut of milk could force prices down. Employment on dairy farms also fluctuated with the seasons.

Although most farm workers were men, dairies were the exception: many women worked in dairies, milking cows or making butter and cheese, throughout the nineteenth century and well beyond. While some were employed to do so, many others were the unpaid wives and daughters of the family who added the milking, or butter-making to their other domestic chores. For some rural women butter making was a welcome source of cash, but the milking might prove more of a chore, especially on cold winter mornings. Chilblains was one common occupational hazard.

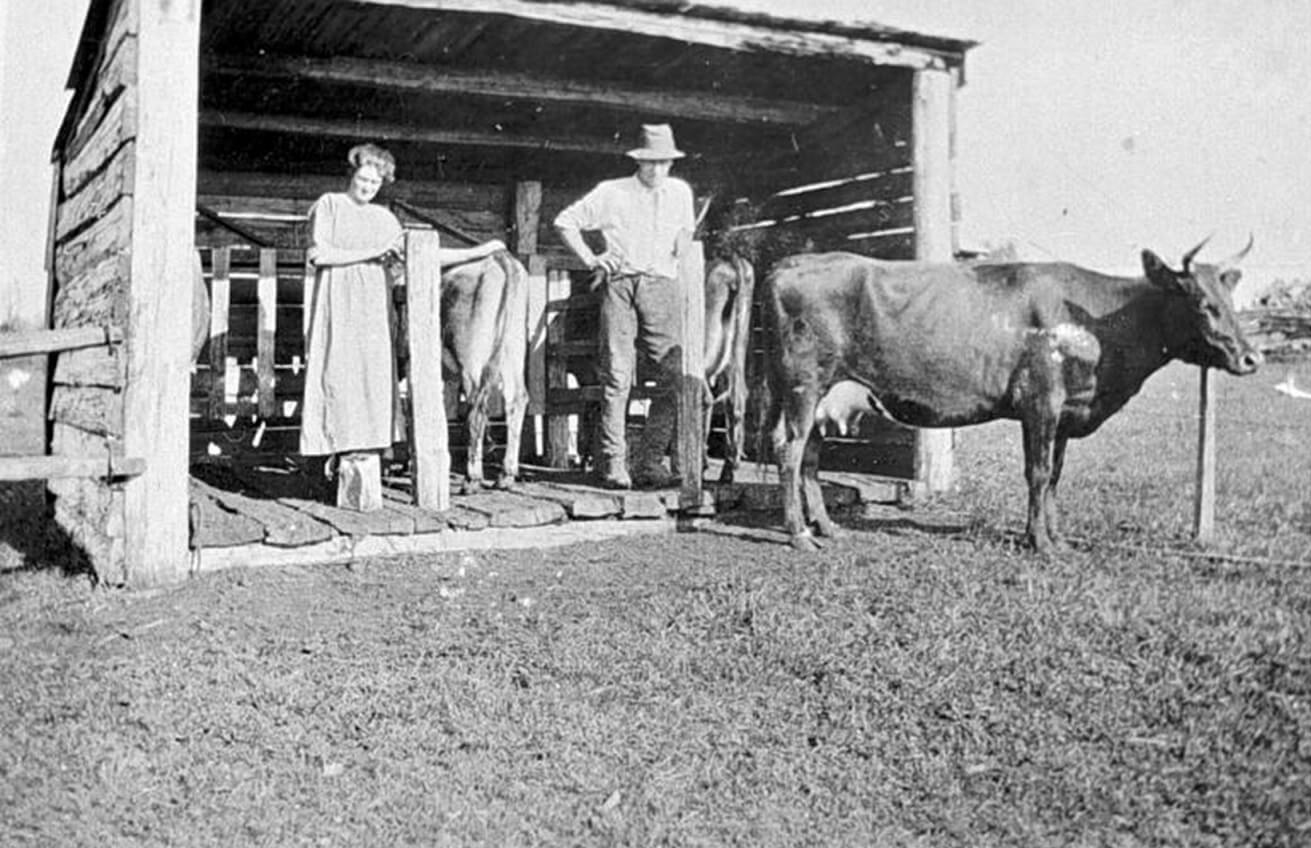

Hand-milking meant that most herds were relatively small, even into the twentieth century. Soldier Settlement farms in particular, were often quite small, with limited carrying capacity. The photograph included here of Mr and Mrs Lockett of Neerim in Gippsland shows a three-stand milking shed, with very basic facilities and minimal protection from the weather.

Mr & Mrs Lockett With Cows at a Three Stand Milking Shed, Neerim North, Victoria, c. 1925.

Reproduced courtesy Museums Victoria

This photograph is assumed to be that of Stanley Herbert Lockett and his wife Silvia Beryl Lockett (née Fitch). They married in 1920 after his return from war service in the Middle East (1915-18) and had two children by the time Stanley applied for a Soldier Settlement block in Neerim (Gippsland) in October 1924. His original block was too small to be a going concern and three years later he applied successfully to acquire an adjoining block. At the time he made the additional purchase his property was classed as dairy and mixed farming. He owned 3 cows, 33 pigs and assorted poultry, but argued that he needed to run a herd of at least 10-12 cows to earn enough to support his family. The Board assessed him as a hard-working and competent farmer, who was likely to be successful. They agreed that his original block was too small. He was still on the property in 1940 when he died suddenly in his sleep at the age of 48, leaving his wife and their four children. We don’t know whether Mrs Lockett remained on the farm or was forced to sell.

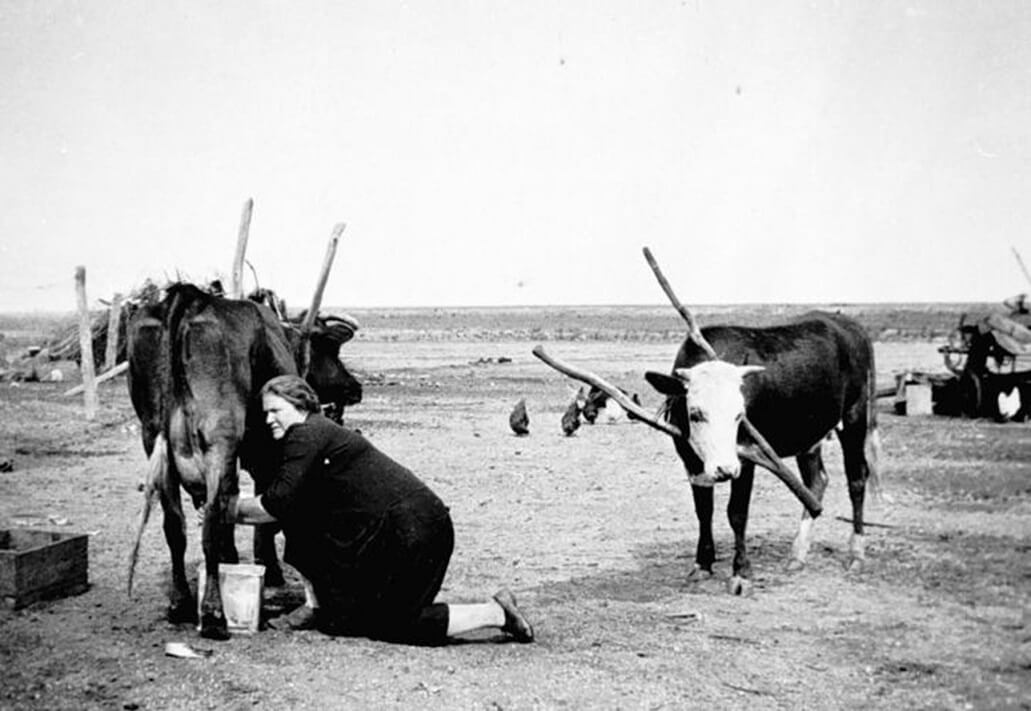

Mrs Eloise Vinen milking in a paddock, Nyah West, 1924

Reproduced courtesy Museums Victoria

Mrs Vinen made butter for her family from the cream. This is milking in the most basic of conditions! Her ‘bucket’ is a cut-down kerosene tin. The collars around the cows’ necks were to prevent them sucking their own udders.

Woman milking a cow, c. 1900

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

In contrast to the work clothes depicted in most photographs of milking sheds, this woman is well-dressed, and wearing white! It is clearly a posed picture, with the woman half-turned to face the photographer.

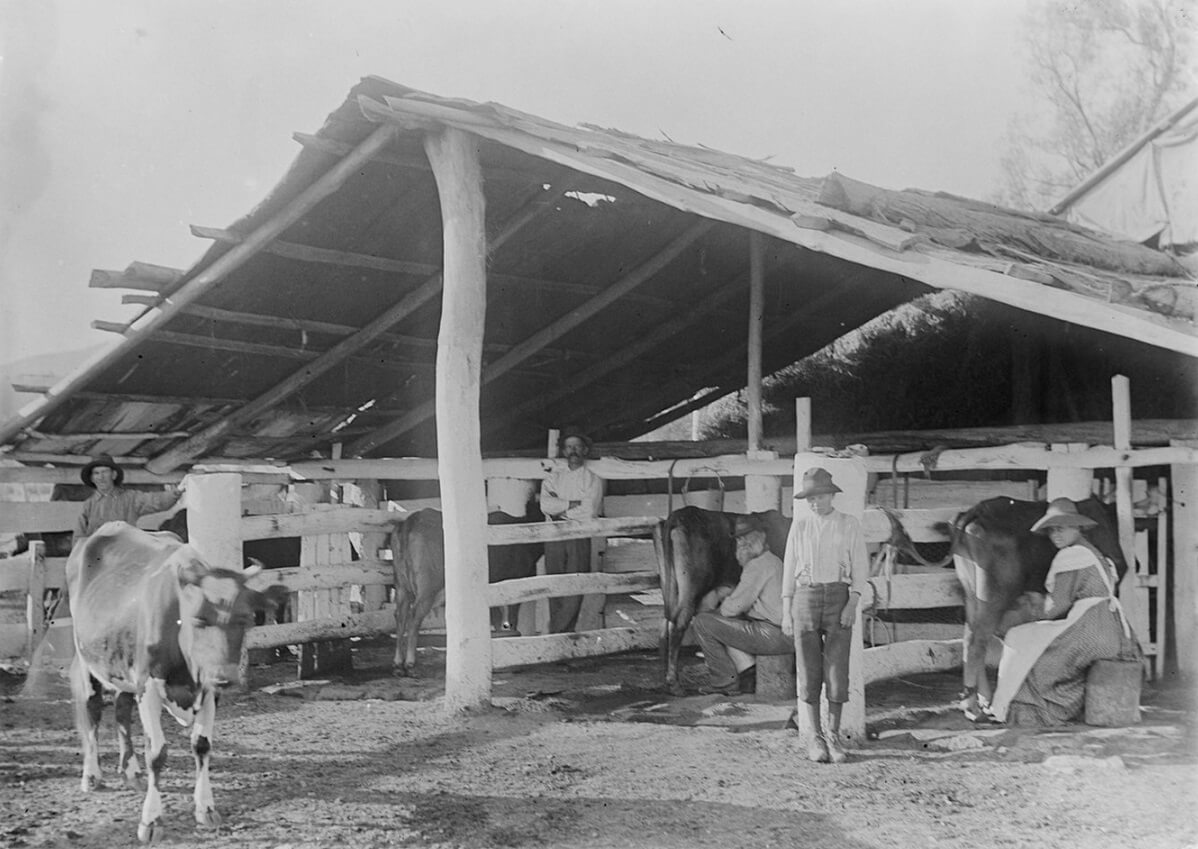

Men and a woman milking, probably in Neerim-north-east, c. 1903-9.

Gabriel Knight photographer

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

Once again the milking shed is roughly-constructed, with an earthen floor and minimal protection from the weather. The milkers seem to be sitting on upturned logs. A young boy is shown in the foreground.

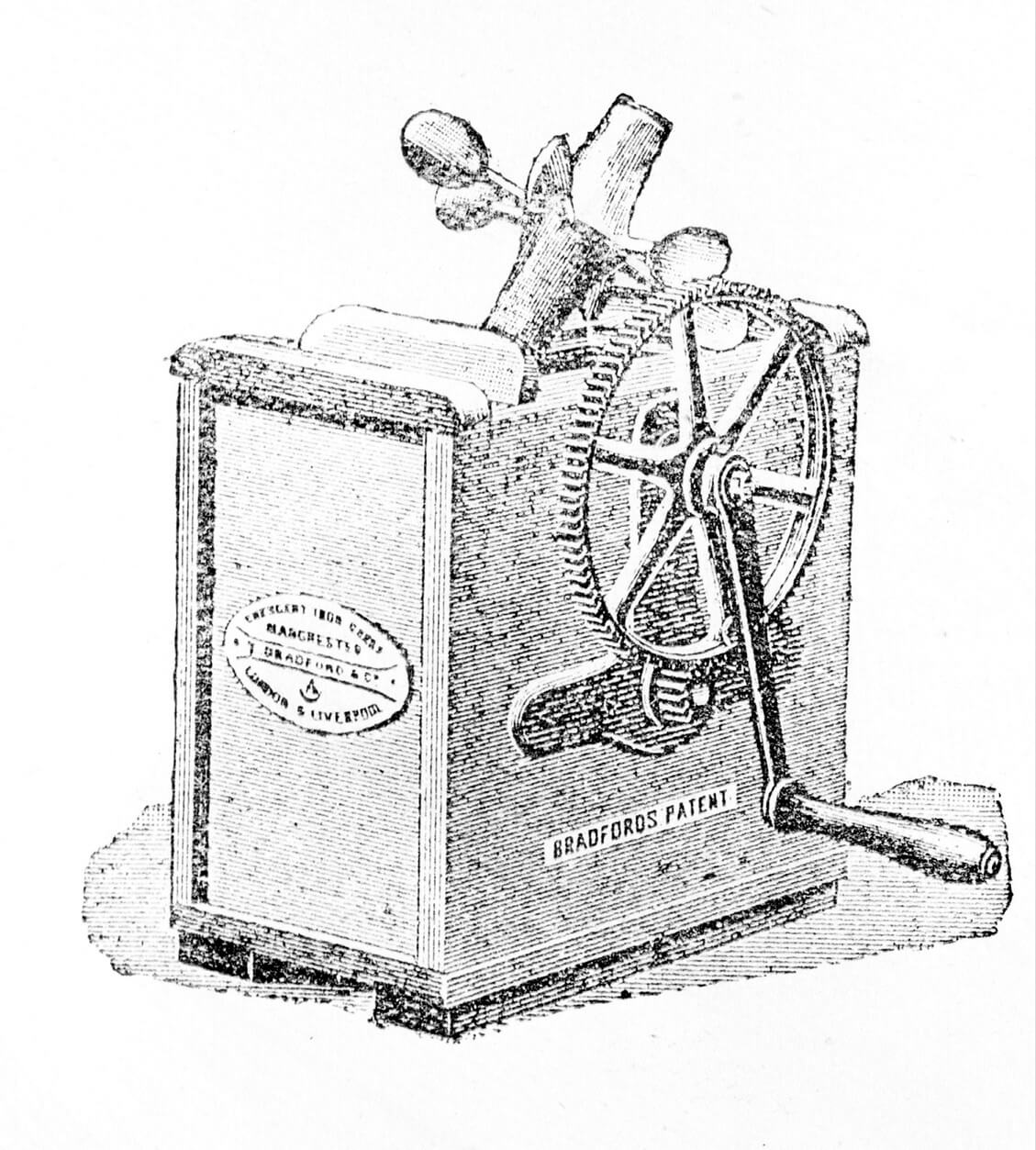

Butter churn, Bradford’s Patent, the Illustrated Australian news, 1 February 1894

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

This butter churn was advertised as ‘rapid butter making’.

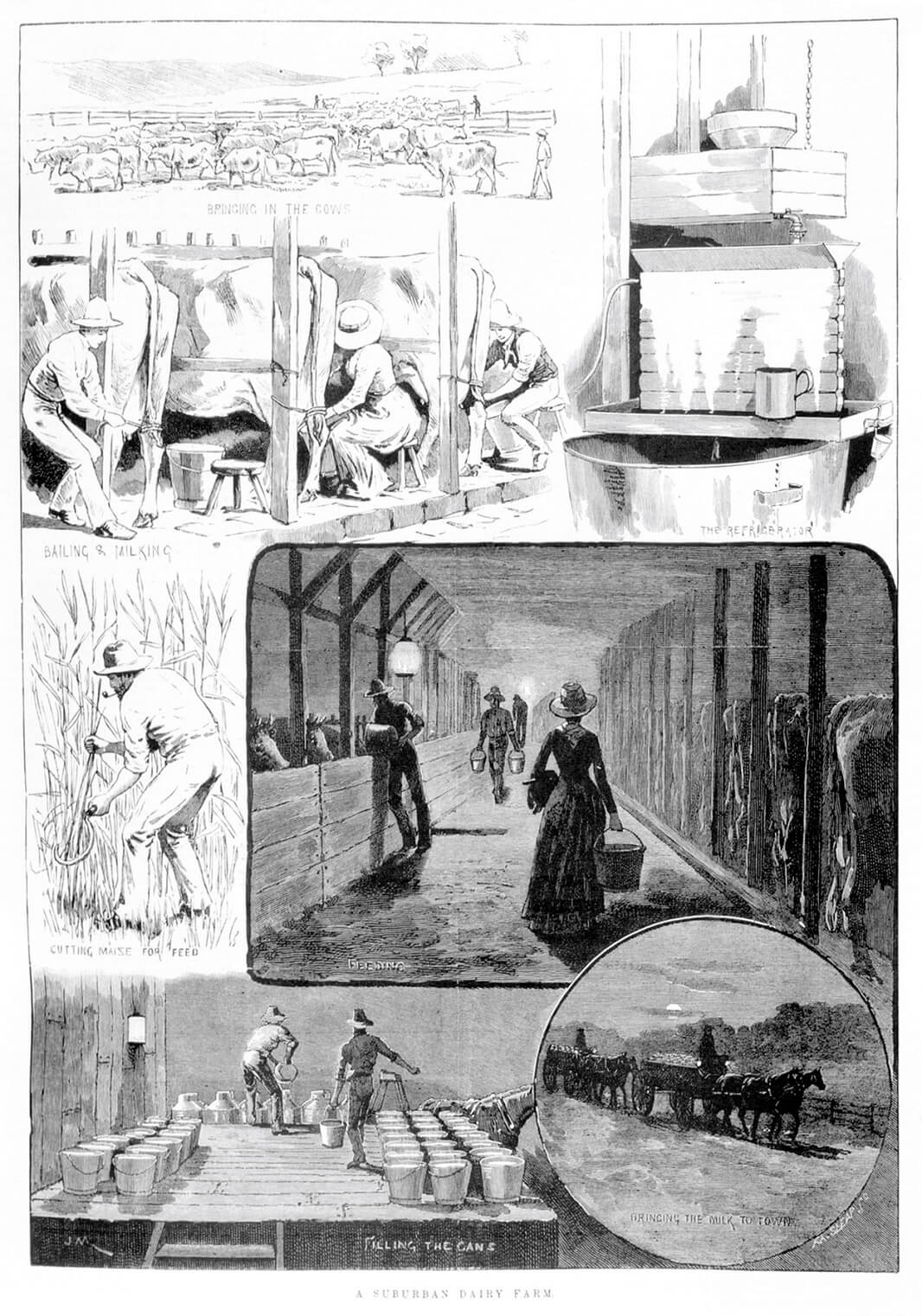

A Suburban Dairy Farm, 1888. Wood engraving, F A Sleap engraver, the Illustrated Australian news, 31 March 1888

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

Individual illustrations show herding the cows, bailing and milking, cutting maize for feed, feeding, filling the milk cans and taking the milk to town. Of interest is the top right inset illustration of ‘the refrigerator’, very much an innovation at this time. This is a large dairy, employing both men and women to milk and care for the cows.

Refrigeration

Several inventions transformed the dairy industry in Victoria in the late-nineteenth century. They were refrigeration, cream separators and a device for testing accurately for butterfat content. They should have included sterilization, adopted in Scandinavia from about the 1880s, but Australia was slow to adopt this basic approach to food safety. Refrigeration was the real game-changer, but it was expensive, and at first was concentrated in large dairies and in factories. However it allowed farmers to deliver either cream, or whole milk to the factory while fresh. Steam-powered separators then extracted the cream far more efficiently than the old pan method. Later cream separators were developed for use on farms, but this was a mixed blessing. It allowed farmers to separate the cream on the spot, rather than having to take whole milk to the factory daily, but also meant that cream was accumulated on farms in unrefrigerated storage areas, resulting in a deterioration in quality.

Soon there was a network of butter factories and creameries throughout dairying districts. The Victorian Railways also built cool rooms at stations in dairying districts, with a large government coolstore in Melbourne. An export trade in butter developed, with refrigerated transport on fast steamers. It helped that Australian produce was available when British and European butter was in short supply out of season. Some 15 million pounds of butter was made in Victoria in 1891, although two-thirds of this was still made on farm dairies. By 1894 production had grown to 40 million pounds, with two-thirds made in butter factories. Exports grew significantly over the same period, increasing from less than £2 million in 1890 to £23 million by 1894, but the trade fluctuated in the pre-war period, with quality-control issues and increased competition.

Charles Pettaval with mechanical milk separator, Budgeree, Gippsland, 1910

Reproduced courtesy Museums Victoria

Loading at the Government Cool Store, c. 1927

Reproduced courtesy Public Record Office Victoria

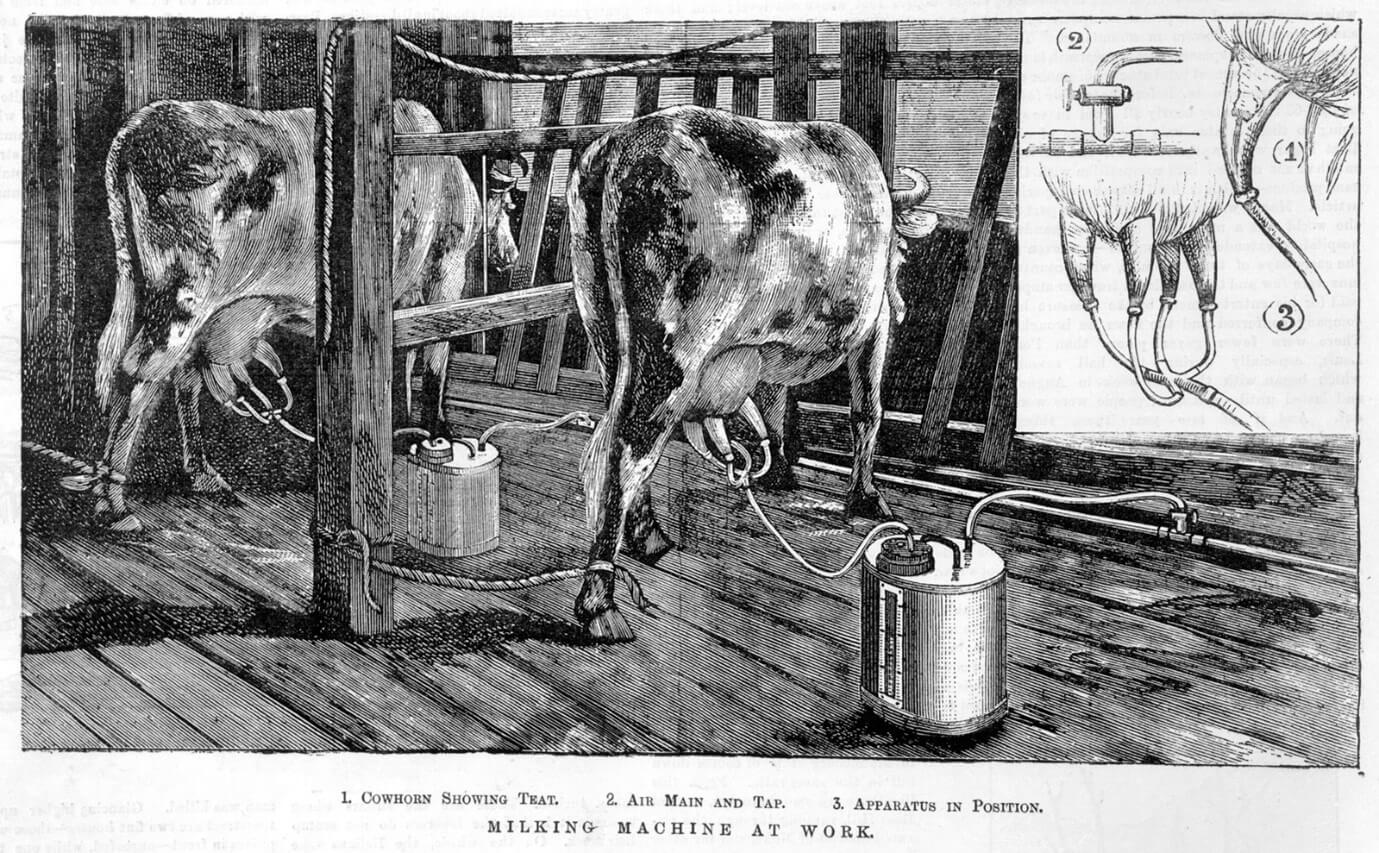

Milking machines

Most dairy herds continued to be small well into the twentieth century. Returns were so low, that few farmers could afford to hire extra labour and were limited by the capacity of family members to milk the cows. The invention of milking machines eventually solved this problem, although the first models were cumbersome and difficult to clean. In the absence of sterilization equipment, they may well have been dangerous sources of contamination in the early years of use.

Milking machine at work, wood engraving, 1892

Illustrated Australian news, 1 June 1892

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

In the meantime, plenty of cows were still milked by hand up until the Second World War, as members of the Australian Women’s Land Army discovered when they were assigned to dairy farms.

Dorothy Arrowsmith of the Australian Women’s Land Army hand milking, 1941-43

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria