Gold mining

The discovery of gold in Australia in 1851, first in New South Wales, then in Victoria, made headlines around the world. All over Victoria men downed tools and rushed to the fields, leaving Melbourne and other regional towns deserted. Employers despaired of finding workers, while women were left to manage alone. Soon the locals were joined by thousands from overseas. During 1852 45,000 passengers arrived from Britain alone, while thousands more travelled from New Zealand, Europe, America and China, most heading to the latest field. It is hard now to understand the near-hysteria that greeted each gold rush. But for many working men finding gold represented a once-in-a-lifetime chance to escape a life of wage-labour and perhaps even become a ‘master’ themselves. Few could hope to do this at home. Women also shared in the dream. Those who travelled alone or accompanied husbands or brothers on the hazardous sea voyages from the northern hemisphere, wrote that they hoped to ‘better themselves’. As Lucy Hart put it in a letter to her mother in May 1852: ‘what was it for all to try to do something for ourselves so that my husband should not allways work under a Master and happy am I to inform you that we gained that point he is now his own Master’. Even better, Lucy no longer had to work so hard herself. No more taking in other people’s washing for her! ‘[N]ow I consider myself well off in the world so I do nothing but my own work now’. The Harts were among the lucky ones. John Hart managed to find enough gold in Ballarat to buy himself a horse and cart, which he used to cart supplies to the goldfields — a far more secure way to earn a steady income than digging for gold.

Gold seeking was hard work, even looking for the alluvial gold that lay just below the surface. Miners worked small claims, shoveling dirt through sieves, or rocking the gravel from the beds of streams in cradles to separate the tiny specks of gold. Those unused to heavy labour often gave up quickly. William Howitt, a Quaker writer and journalist who travelled through the Victorian fields from 1852-4, had this advice for would-be diggers:

advise him first to go and dig a coal-pit; then work a month at a stone-quarry; next sink a well in the wettest place he can find, of at least fifty feet deep; and finally, clear out a space of sixteen feet square of a bog twenty feet deep; and if, after that he still has a fancy for the gold-fields, let him come.

-William Howitt, Land, Labour and Gold, 1855.

Few heeded his advice and each new field was soon crowded with eager gold-seekers, all hoping to find the elusive nugget. Few made their fortunes, although those who arrived at the gold fields very early were more successful than those who came later. William Howitt described gold-seeking as ‘a lottery, with more blanks than prizes’.

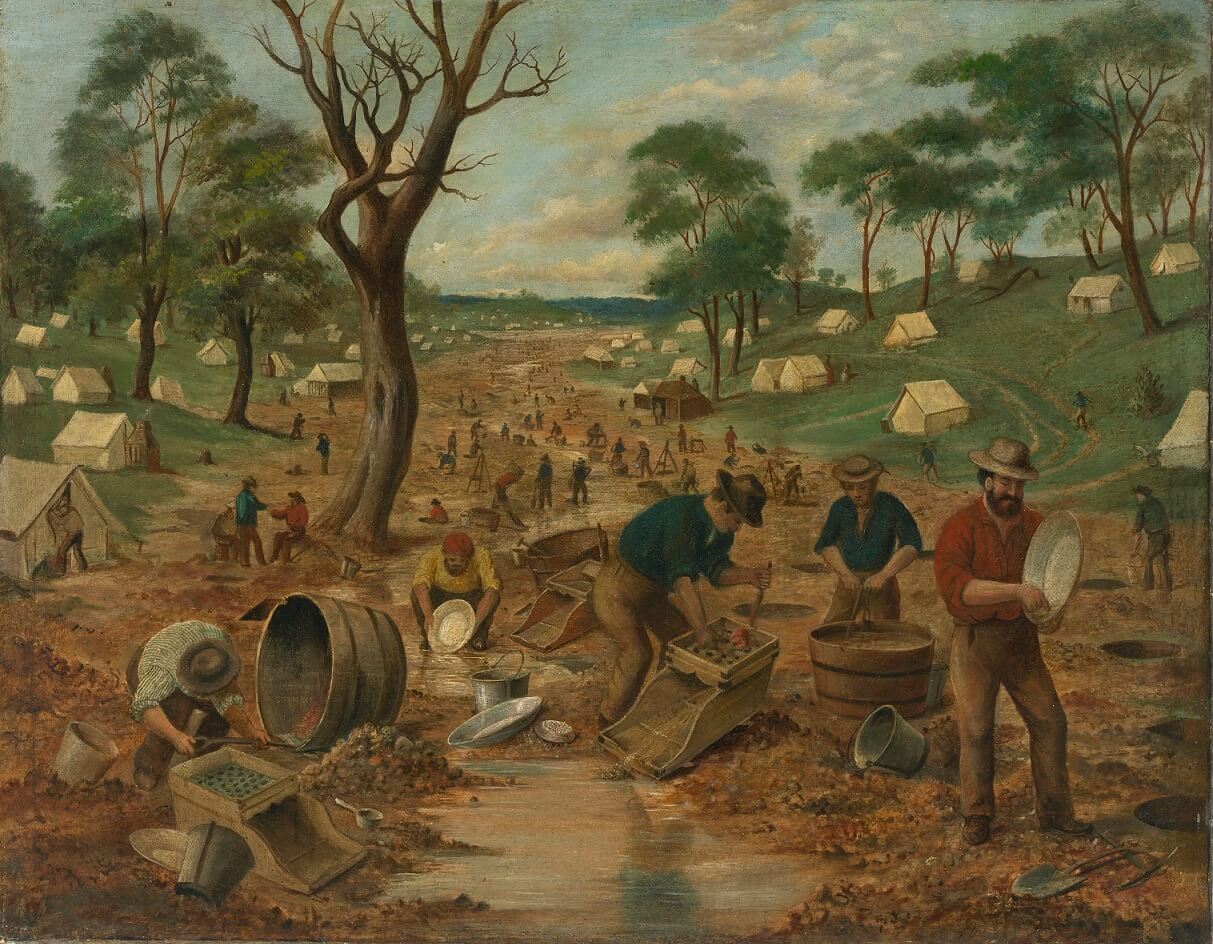

Australian gold diggings by Edwin Stocqueler, c.1855

Courtesy National Library of Australia

In this picture diggers are shown crowded along the banks of a tiny stream, panning for gold specks and sifting the dirt through gold cradles. Holes have been dug all along the banks of the stream, while tents are dotted on the surrounding hillsides. The work was relentless, carried out in all weathers, for an uncertain return.

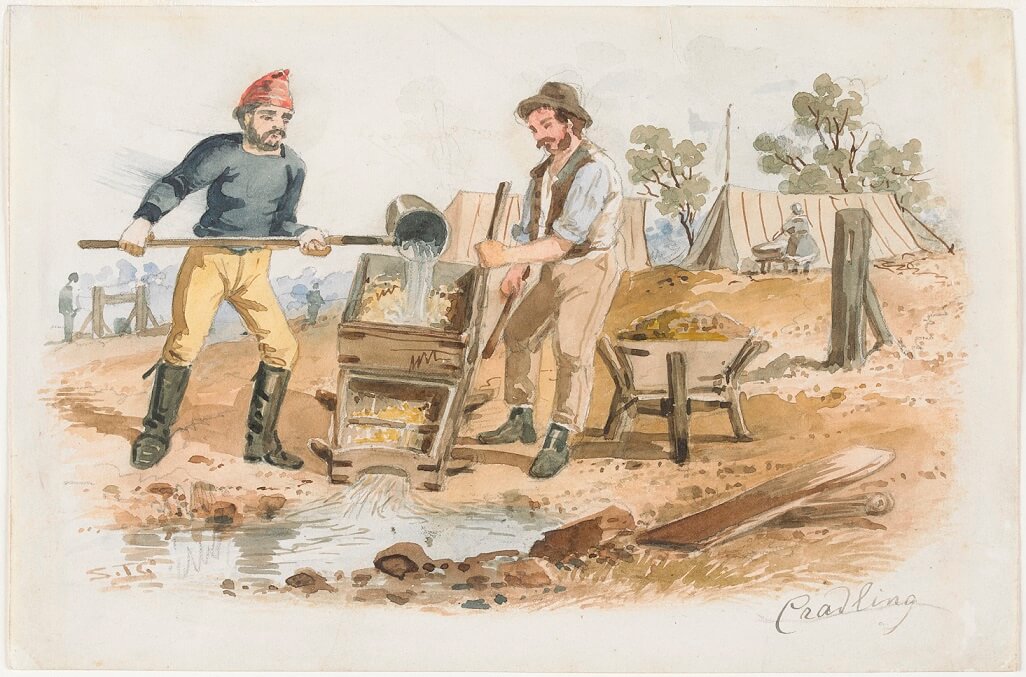

Cradling, Watercolour by S.T. Gill, 1869, from a sketch completed in the 1850s.

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

Cradling for alluvial gold required the basic tools of a wheelbarrow, pick and shovel, a bucket and a cradle, as illustrated here. Dirt and water was shovelled into the cradle and rocked to wash the dirt through a sieve, leaving gold behind. As shown here, miners often worked in pairs to save time, but also to spell tired muscles.

Zealous Gold Diggers, 1852. Watercolour, by S T Gill.

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

Family groups sometimes worked together. This sketch shows a woman rocking the gold cradle, a sleeping baby in her arms, while a young child, possibly a little girl, shovels dirt. The man is pouring water from the stream into the cradle. Behind them another man is digging a hole with a pick.

Quite apart from the heavy work, the Victorian gold fields were hazardous places. Accidents abounded, as men (or children) fell down shafts, were injured by tools, firearms, or in blasting accidents, or were asphyxiated in mine shafts or tents. Living conditions were primitive. Many lived in unlined tents, with little in the way of comfort, while hygiene was minimal. Drinking water was often drawn from the same streams the diggers worked and was soon heavily polluted. In the summer streams might run dry, while the danger of dysentery or typhoid fever, caused by pollution from sewage and other ‘nuisances’, increased many fold. More than 1,000 miners died from typhoid fever near Bright in 1854, while child mortality was high on every gold field.

The alluvial gold was soon exhausted and miners were force to seek gold in the quartz reefs underground. Some of these reefs could be reached by small groups of miners digging shafts manually, although it was very hard work, with no guarantee of success.

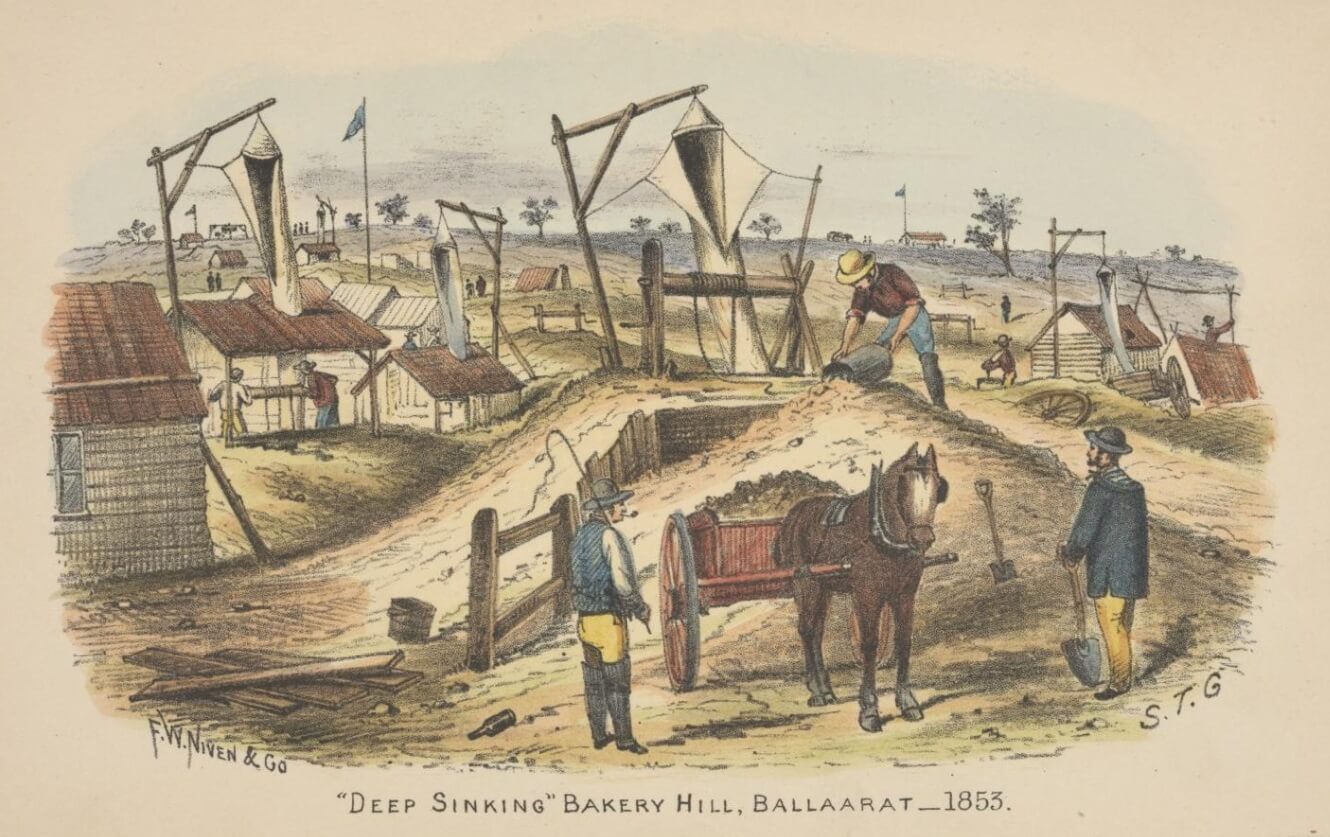

“Deep Sinking” Bakery Hill, Ballaarat – 1853

Watercolour by S T Gill

Reproduced courtesy National Museum of Australia

In this watercolour from 1853 artist S T Gill shows small groups of miners grouped around shallow shafts. Hand-operated windlasses brought dirt and rock to the surface. This was dangerous work, as shafts could collapse without warning, or miners could be poisoned by ‘bad air’. As the shallow reefs were exhausted in their turn, miners needed heavy machinery to reach the deeper leads. This was too expensive for small cooperatives and by the 1860s most miners worked as employees of large mining companies. Dreams of wealth and independence were often short-lived.

Gold was first discovered in Walhalla in the early 1860s, but the alluvial gold was soon exhausted. Tunnelling to reach the rich gold seams underground required the resources of companies like the Long Tunnel Mining Company, which became one of the richest gold mining companies in Victoria. By 1914 it had extracted over 30 tons of gold. However by the 1890s the focus of world attention had shifted to the new rich gold fields in Western Australia. Fewer men who remained earned a living mining gold.

Coal

Meanwhile Victorian industry was dependent on supplies of coal from New South Wales. When major strikes in 1888 disrupted supply for nearly six months, greater efforts were made to find local sources of fuel. There was some success in the 1890s, with the Coal Creek Mining Company developing settlements around deposits in Korumburra, Jumbunna and Outtrim in Gippsland. By 1900 they supplied about one-third of Victoria’s needs. However the mines were poorly managed and exploitation of the workers led to a major strike and lock-out in 1903, which reduced output and threatened the survival of the industry. Government urgently sought alternative sources of coal.

‘Victoria’s First Load of Korumburra Coal, October 28, 1892’

Reproduced courtesy Public Record Office Victoria

State Coal Mine

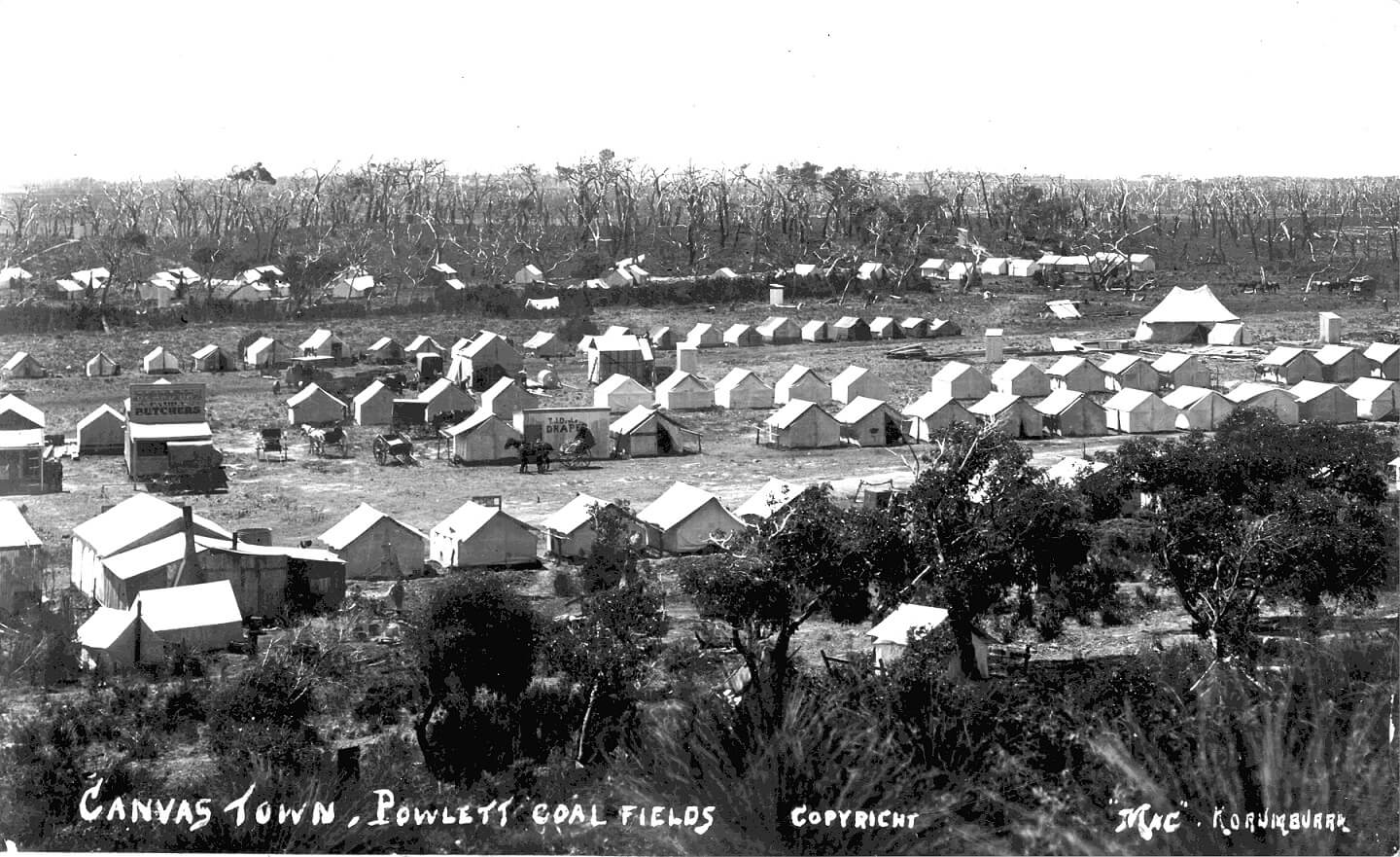

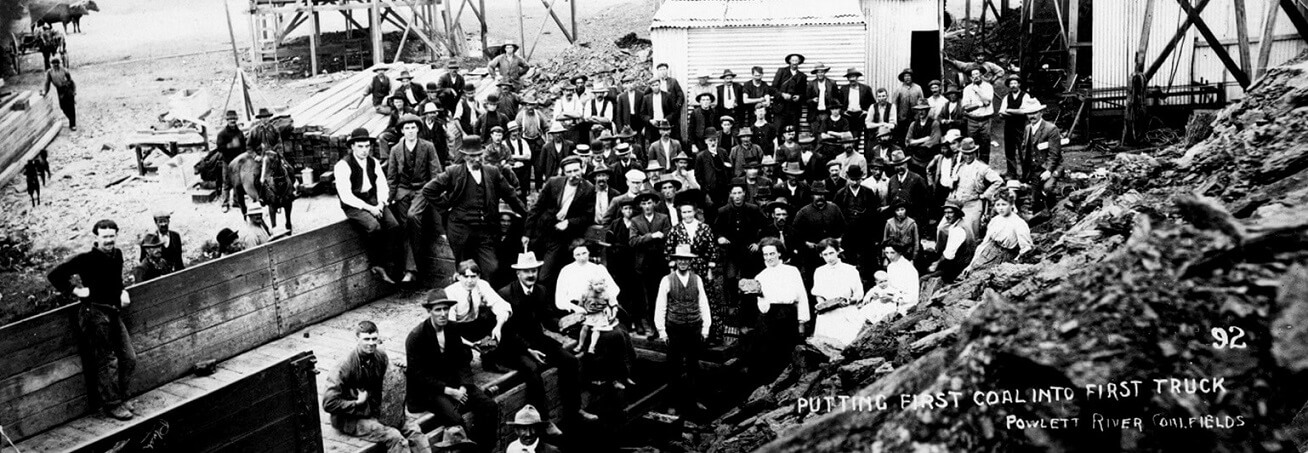

In 1908 a rich coal seam was discovered accidently by a government survey team sinking a well for drinking water near Powlett River, and when a further strike disrupted supply from New South Wales in 1909, government quickly resolved to create the State Coal Mine at Wonthaggi. Within a year several thousand miners and construction workers were housed in a tent city laid out around the mine, while work began on building a model town in Wonthaggi.

‘Canvas Town, Powlett Coal Fields. Photographer: ‘Mac’ Korumburra, c. 1910.

Reproduced courtesy Public Record Office Victoria

In 1911 the mine was placed in the control of the Railway Commissioners, and the coal produced freed the railways from the necessity to import coal. The mine was well-run and remained profitable for the next two decades. The township and community of Wonthaggi was close-knit, with most inhabitants directly dependent on the mine for their livelihood. Unionism was strong. The State Coal Mine maintained profitability until the onset of the Great Depression, after which output declined and the brown coal deposits discovered near Yallourn took over.

Knocking Down Coal, State Mine, Powlett, ‘09

Postcard, 1909

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

Working conditions

Mining was always difficult and dangerous work. While safety standards steadily improved, miners still worked in dark, dusty conditions with little protective equipment. Many developed lung disease in later life. Ironically the introduction of mechanised drills probably increased the danger of disease, since they produced fine dust that was easily inhaled into the lungs. But the hazard miners feared most was the danger of rock falls, or explosions caused by igniting coal gas. One such tragic accident took place in Wonthaggi’s Twenty Shaft in February 1937, when a huge explosion travelled nearly one mile underground, and sent a cloud of coal dust 100 feet into the air. Thirteen men died in the shaft. It followed months of protracted debate about safety standards in the mine, with unionists concerned about declining standards.

Aerial view of no. 20 shaft at Wonthaggi Vic. Taken on Monday, 15th Feb. 1937 from a special Sun plane. Sun news pictorial, 9 April 1937

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

Post-war mining

The State Mine at Wonthaggi managed to survive the Second World War, but on a reduced scale. By 1958 it was clear that the mine would close. Miners were retrenched and the number employed in the mine continued to fall in line with declining production. In December 1968 the mine finally closed. Huge reserves of brown coal remain in Victoria, mostly in Gippsland and the La Trobe Valley and these continue to power electricity stations. However the use of fossil fuels is increasingly controversial, as the world tries desperately to limit global warming. Awareness of the urgency of the climate emergency and government commitments to reducing Victoria’s carbon footprint, mean that the future of the coal industry is uncertain. The production of energy from renewable sources is likely to assume increasing importance in the future.

Further reading

Marian Aveling & Joy Damousi (eds) Stepping Out of History: Documents of Women at Work in Australia. Allen & Unwin, North Sydney, 1991.

Geoffrey Blainey The Rush That Never Ended. Melbourne University Press, 1963.

Charles Fahey The Wonthaggi State Coal Mine. Department of Conservation and Lands and the State Mine Preservation Committee, Wonthaggi, 1987.

Andrew Reeves Up From the Underground: Coalminers and Community in Wonthaggi 1909-1968. Monash University Publishing, Clayton, 2011.