Of all the misguided actions of the past, the deliberate introduction of rabbits to Victoria must top the polls. Although earlier attempts to introduce rabbits in New South Wales failed, brothers James and Thomas Austin had spectacular success when they imported two dozen pairs of rabbits to their Barwon Park property in about 1860. True to their nature, the rabbits soon multiplied, spreading into neighbouring properties and thence throughout Australia at the spectacular rate of between 70 and 100 kilometres per year. Literally nothing seemed to stop them and soon they were devastating crops and grazing land throughout Victoria and beyond. By the early 1870s there were major colonies in the Mallee and districts around Colac, with similar breeding grounds in Geelong and the Otway Ranges. In dry years they descended on crops with devastating ferocity: one farmer lost all 70 acres of his wheat crop in five days and feared being forced to give up his land! Farmers spent valuable time and energy digging out warrens, trapping and poisoning the rabbits, but they could not clear them from adjacent scrub or grazing land. Soon there were literally millions of the pests.

However the proliferation of rabbits also created an employment opportunity in rural areas, as men were hired to keep them in check. Some worked full-time as rabbiters, while others added trapping rabbits to a daily or weekly work schedule. Farm children often trapped rabbits and became expert at digging out burrows. ‘Underground mutton’ as rabbit was called was a staple of farming diets, and urban diets too until well after the Second World War. The introduction of the virus myxomatosis in Australia in the 1950s finally brought the rabbit ‘plague’ under control.

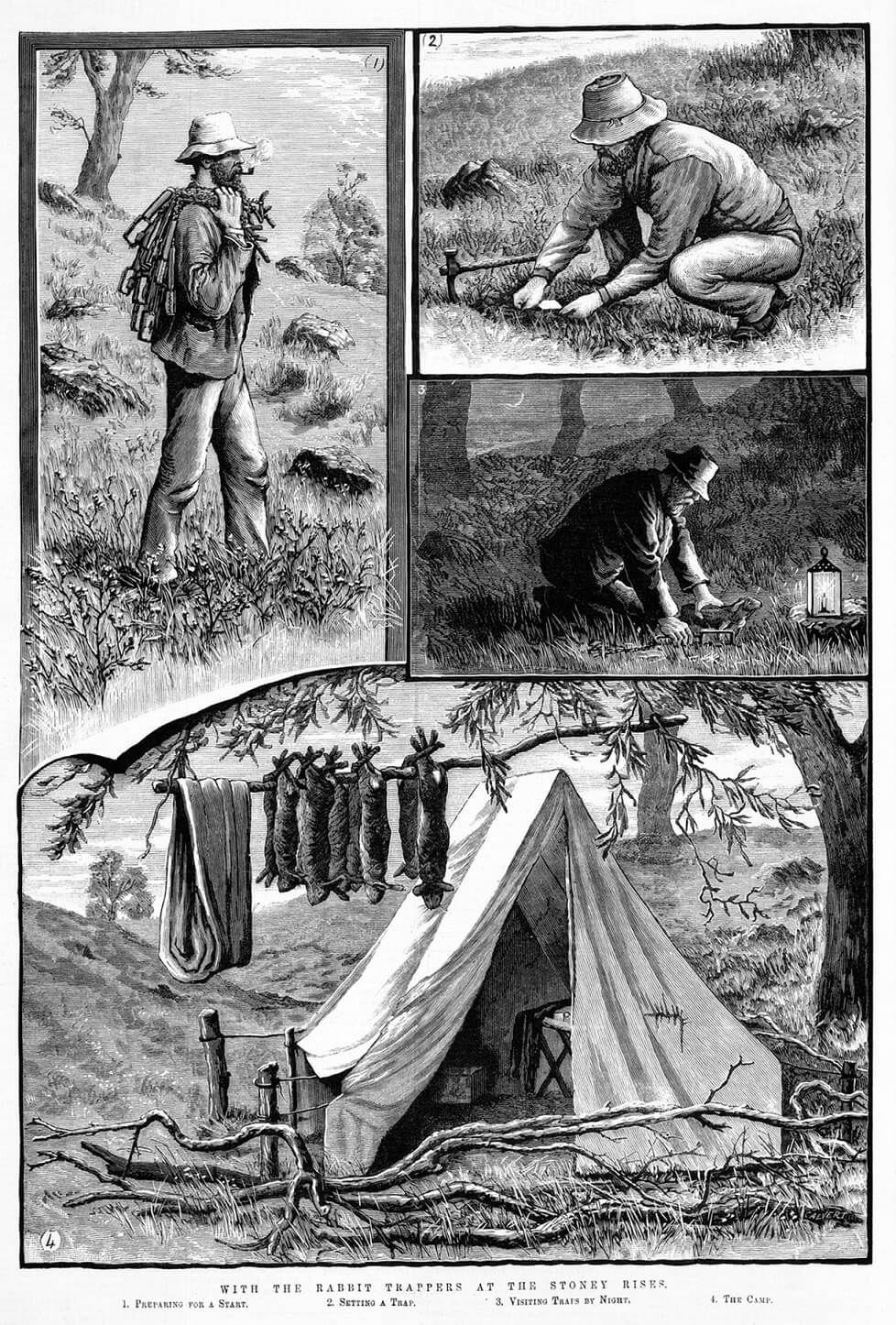

With the rabbit trappers at the Stoney Rises, 1884. Samuel Calvert, engraver.

Published in the Illustrated Australian news, 19 March 1884

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

The individual images show: 1. Preparing for a start. 2. Setting a trap. 3. Visiting traps by night. 4. The camp.

Rabbit traps were ubiquitous for much of Victoria’s history. They were set open, generally buried just below the surface of the ground near the mouth of a burrow, and were triggered when weight was applied to the pressure plate, trapping the animal in the jaws of the trap. The suffering animal did not always die in the process and was often despatched by the trapper. Unlike England, there were no anti-poaching laws in Victoria, and rabbit trapping was widespread.

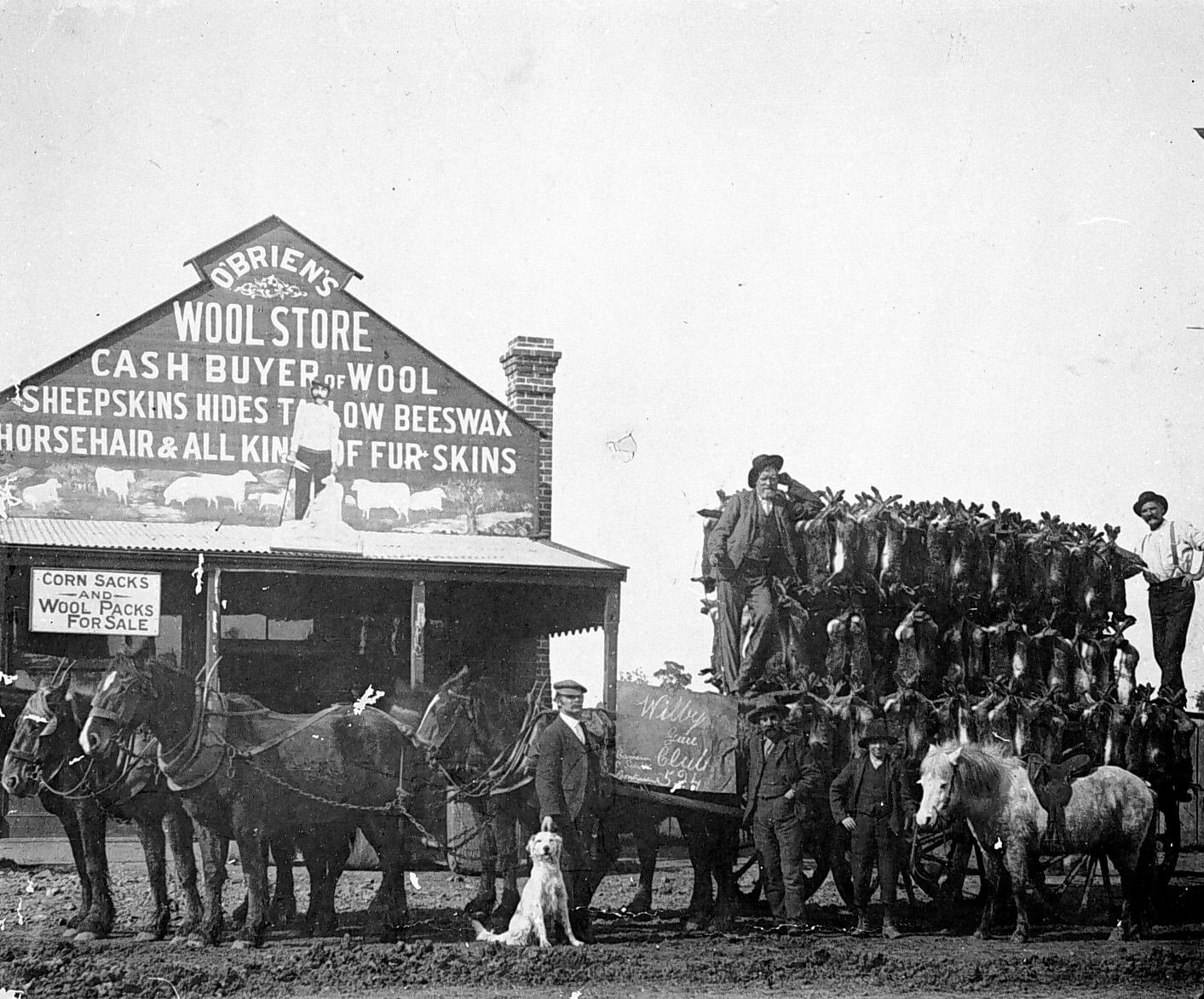

Two professional rabbiters with their wagon, c. 1915

Reproduced courtesy Museums Victoria

Results of a ‘hare drive’, Yarrawonga, 1904

Reproduced courtesy Museums Victoria

Local gun clubs sometimes organised rabbit, or in this case, hare ‘drives’. This was the result of one such activity conducted by the Wilby Gun Club. They shot 524 hares which they brought to a local dealer in fur and skins.

Men with a catch of rabbits, Worouly district, c. 1930

Reproduced courtesy Museums Victoria

The men have adopted the nick-name ‘The Wanderers’. Their rabbits are strung on the back a horse-drawn cart, but four of the men are obviously travelling by bicycle.

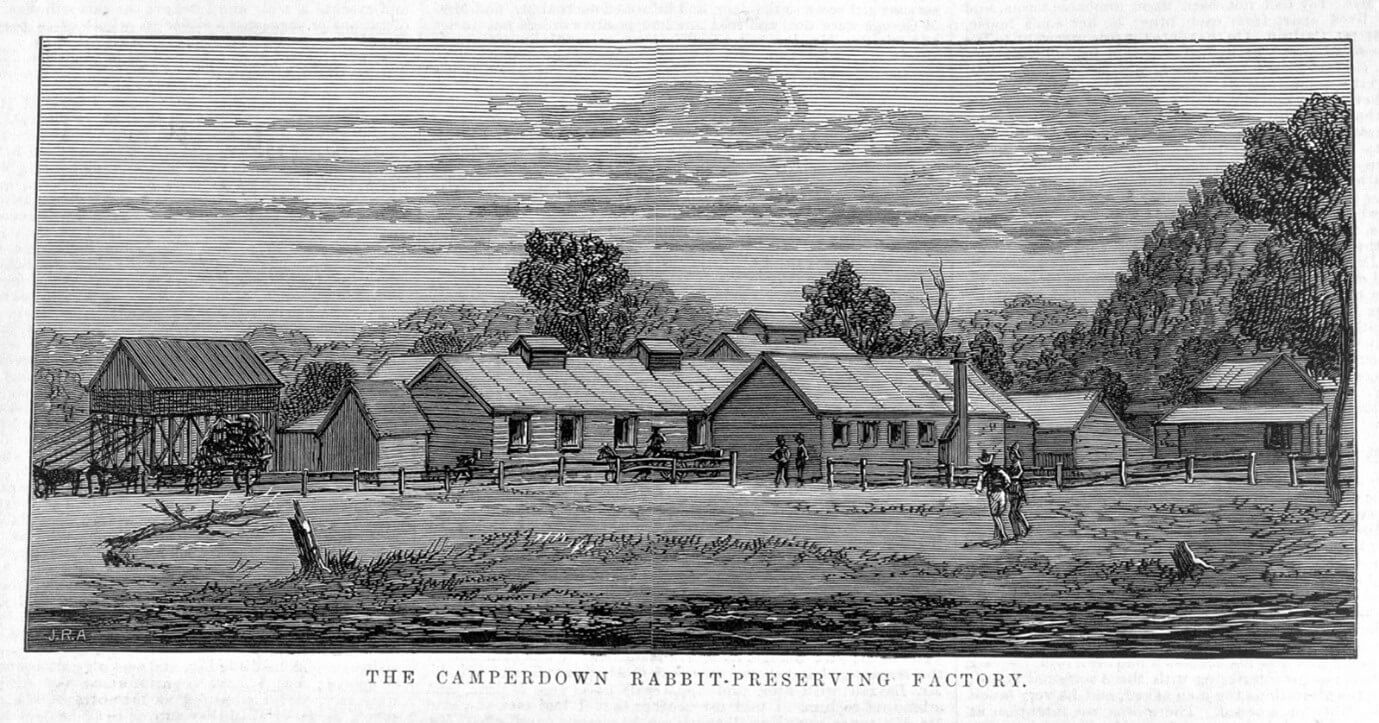

Catching and processing rabbits was an early industry in Victoria. At first the meat was cooked and canned at factories based in Colac and Camperdown, but with the introduction of refrigeration it was possible to pack and export frozen rabbit carcasses. Soon exporting rabbit meat was a thriving industry. Rabbit fur was also a commodity. It was popular for women’s hats, capes, coats and stoles and as a trimming for collars or dresses until the 1970s. Rabbit fur was also used to make felt hats.

The Camperdown Rabbit-preserving Factory, 1881

Julian Rossi Ashton, print published in the Australasian Sketcher, 9 April 1881

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

The factory preserved rabbit meat in cans and dried the skins in open sheds, shown on the left of the picture.

A truck load of rabbits, 1930

Reproduced courtesy Museums Victoria

During the Great Depression of 1929-33+ many men took to the roads in search of work. These men may have been working for the owner of the truck, perhaps shown on the left. Rabbit was a cheap meat for many families during the Depression.

By the 1940s exporting rabbit carcasses was big business in Victoria and one man had the market cornered- Jack McCraith, known popularly as the ‘Rabbit King’. J A McCraith Rabbit Merchants established a series of 184 depots throughout rural Victoria, New South Wales and South Australia. Local trappers delivered their catches to the depots, from where a network of refrigerated trucks and rail carriages transported the carcasses to McCraith’s Melbourne factory. Until the mid-1950s McCraith’s packed an average of 1,000 cases, or 32,000 rabbits per week. At its peak, the company exported 100,000 carcasses per week. The demand was said to be ‘insatiable’ and the supply ‘inexhaustible’.

The Rabbit King

Packing rabbit carcasses at McCraith’s for export, 1945

Reproduced courtesy National Archives of Australia

Not so it seems. From the late 1950s the advent of battery-farmed chicken created a ready supply of cheap chicken, while competition in the European market saw demand fall there. Myxomatosis proved to be the last straw and the wild rabbit business was soon no more. The once-common ‘underground mutton’, food of the poor, eventually became almost unprocurable and rabbit had all but vanished from Australian diets by the beginning of this century. With the industry went the last of the rabbiters.

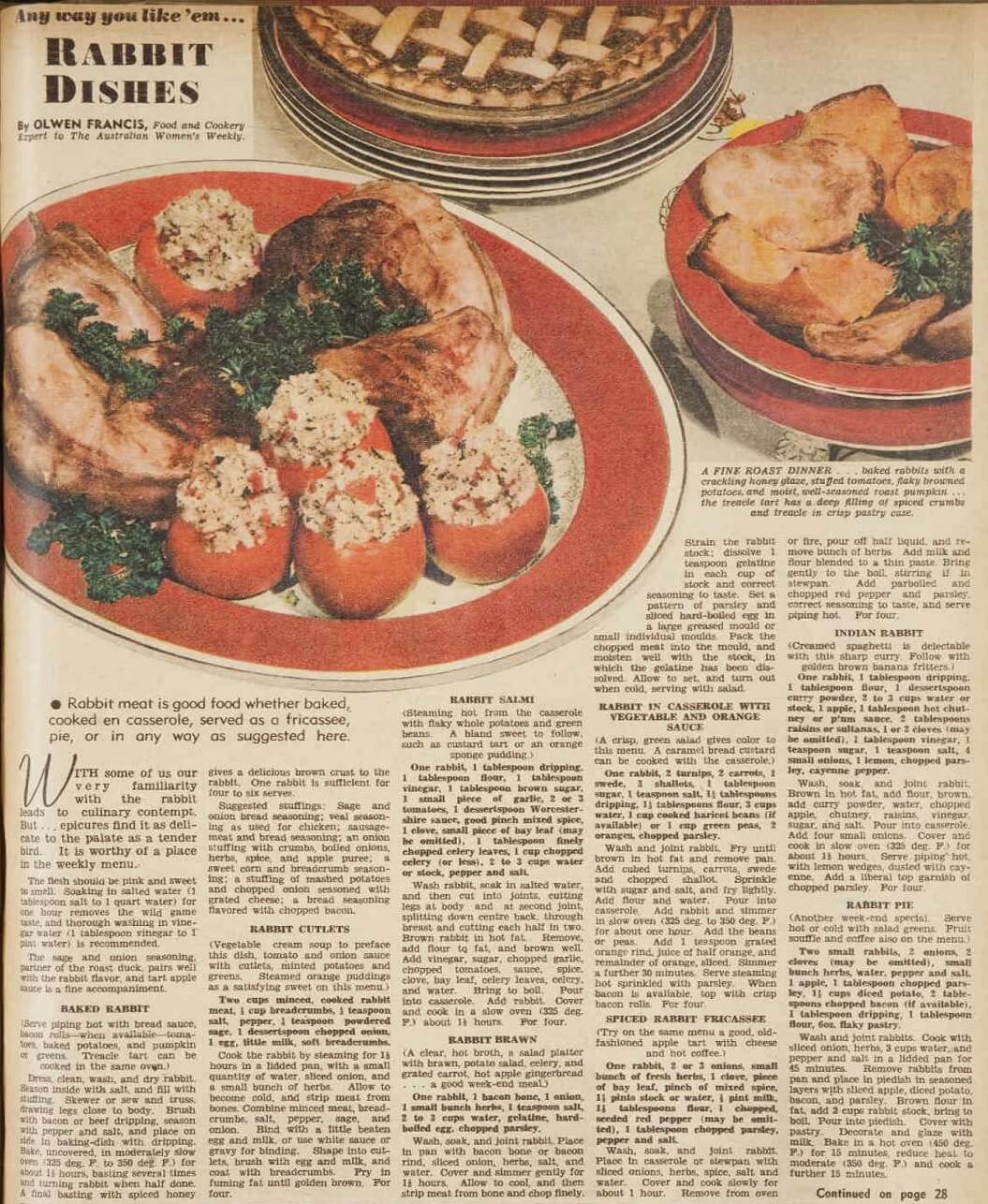

Rabbit dishes, Australian Women’s Weekly, 22 April 1944

Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia

Almost all recipe books in Australia included instructions for cooking rabbit. In this article the Australian Women’s Weekly cooking ‘expert’ Olwen Francis, assured her readers that rabbit meat was ‘good food’, however it was cooked. Recipes included baked rabbit, rabbit casserole and rabbit pie (our family’s favourite). Rabbit had another advantage during the Second World War, as it was not rationed, unlike mutton or beef.

‘What Paris has done to rabbit’, Australian Women’s Weekly, 12 January 1966

Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia

This article celebrates the new-found popularity of the humble rabbit fur!