I appreciate and value to the fullest the great deeds done by our soldiers, and the sacrifices they have made … We can never forget the debt we owe these men. No money manufactured in any mint in the world can repay them for the great sacrifices they have made for us.

Richard Frederick Toutcher, Member Legislative Assembly, 1917

The Great War ended in November 1918. Over 112,000 Victorian men had enlisted and 91,000 served overseas. More than 17,000 were killed.

A grateful nation, determined to repay this sacrifice, offered returned servicemen (and women) an opportunity to farm. The nationwide Soldier Settlement Scheme was established to provide blocks of land on which it was hoped they could rebuild their lives. Across Australia, thousands of returned servicemen took up the challenge and tried their luck on the land.

A land fit for heroes

Following the end of the war, more than 250,000 soldiers returned to Australia’ almost 78,000 to Victoria alone. Despite the promises, not all could find work and public leaders soon grew increasingly uneasy at the large numbers of unemployed soldiers in the cities and towns. Some of these men became a troublesome presence, celebrating their return with drinking and riotous behaviour. Begging in the streets by returned servicemen was also common.

The Soldier Settlement Scheme was developed, in part, to provide thousands of returned soldiers with a livelihood. It was also a reward for the service they had given their country on the battlefield. A ‘land fit for heroes’ was the promise: prosperous farms, contented families and thriving regional development were imagined. Farms were established throughout Victoria, with a range of enterprises — growing grapes (for dried fruit), growing fruit and vegetables, raising pigs and chickens, wheat and sheep farming, and dairying. But the land was not ‘given’ to prospective settlers. Rather, interest-bearing loans enabled returned men (and some women) to buy blocks of land or improve their existing holdings.

Under the Discharged Soldier Settlement Act 1917, Crown lands were ‘opened up’ to settlement. By 1930, the Victorian Government had acquired 2.5 million acres (just over 1 million hectares).

Soldiers disembarking from HMAS Chemnitz, after returning from Europe, Melbourne, 1919

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

Handbook issued by the New Settlers League of Australia, 1925

Reproduced courtesy Victorian Government Library

A number of these handbooks circulated in the 1920s, providing cheerful and optimistic advice to immigrants and returned soldiers.

‘The man that carries the others’, from the New settlers’ handbook to Victoria, 1924

Reproduced courtesy Victorian Government Library

The Soldier Settlement Scheme was based on the belief that primary production would be the foundation of Victoria’s future prosperity.

Administering the scheme

In Victoria almost 12,000 soldiers took advantage of the Soldier Settlement Scheme. Few of them saw their block of land before they bought it, and only 20 per cent had any farming experience. Settlements were established in the dryland farming areas of the Mallee, South Gippsland and the Western District, and in the irrigation areas of the north-west along the Murray, central Gippsland near Maffra and Sale, and the Goulburn Valley.

Getting land

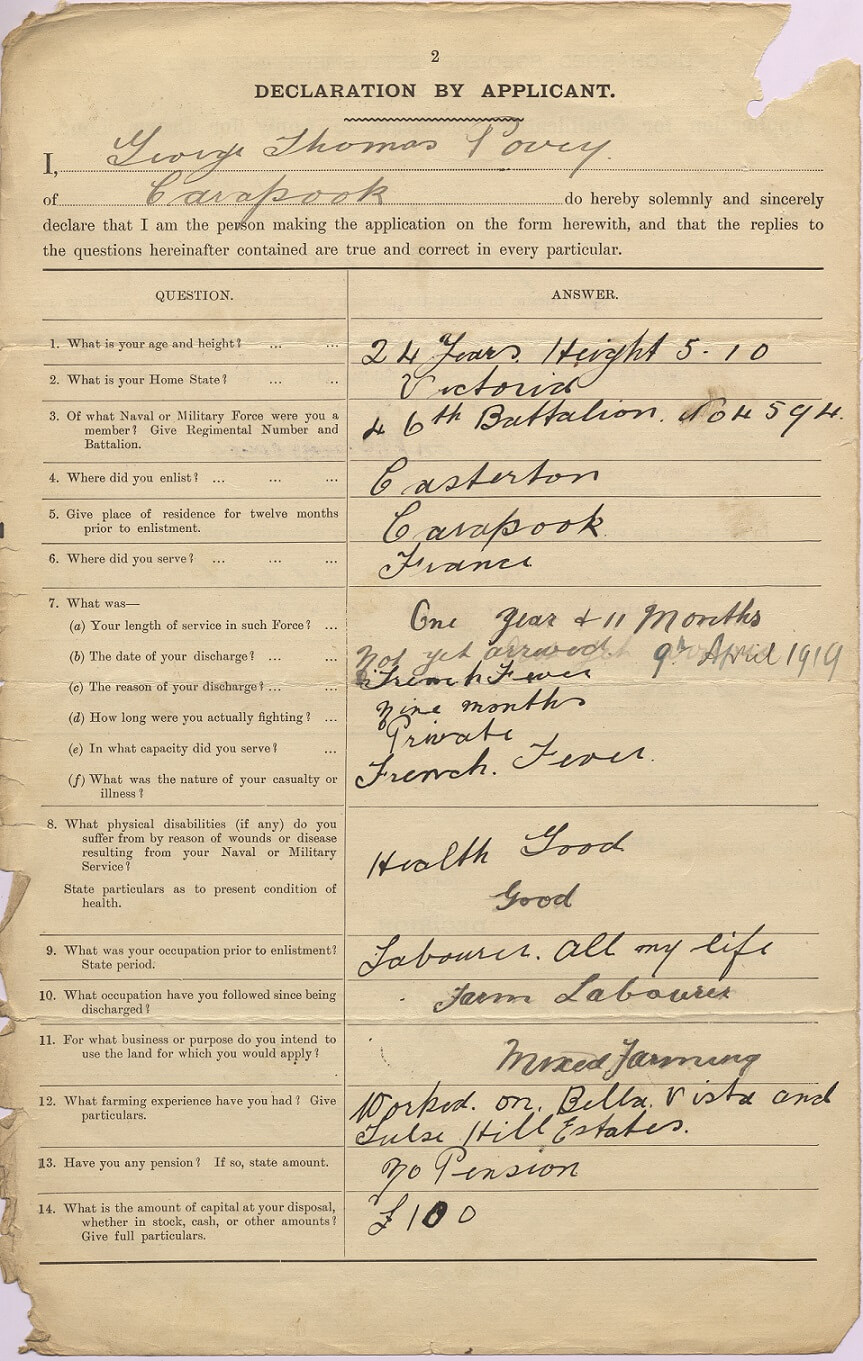

The scheme was first administered by the Victorian Lands Purchase and Administration Board and, from 1918, by the Closer Settlement Board. A hopeful settler had to submit an application form and attend an interview with the Closer Settlement Board. He would be asked how much money he had, whether he had a family, whether he or his wife had any farming experience, his occupation before enlisting, the nature of his war experience, the state of his health and the nature of any disabilities.

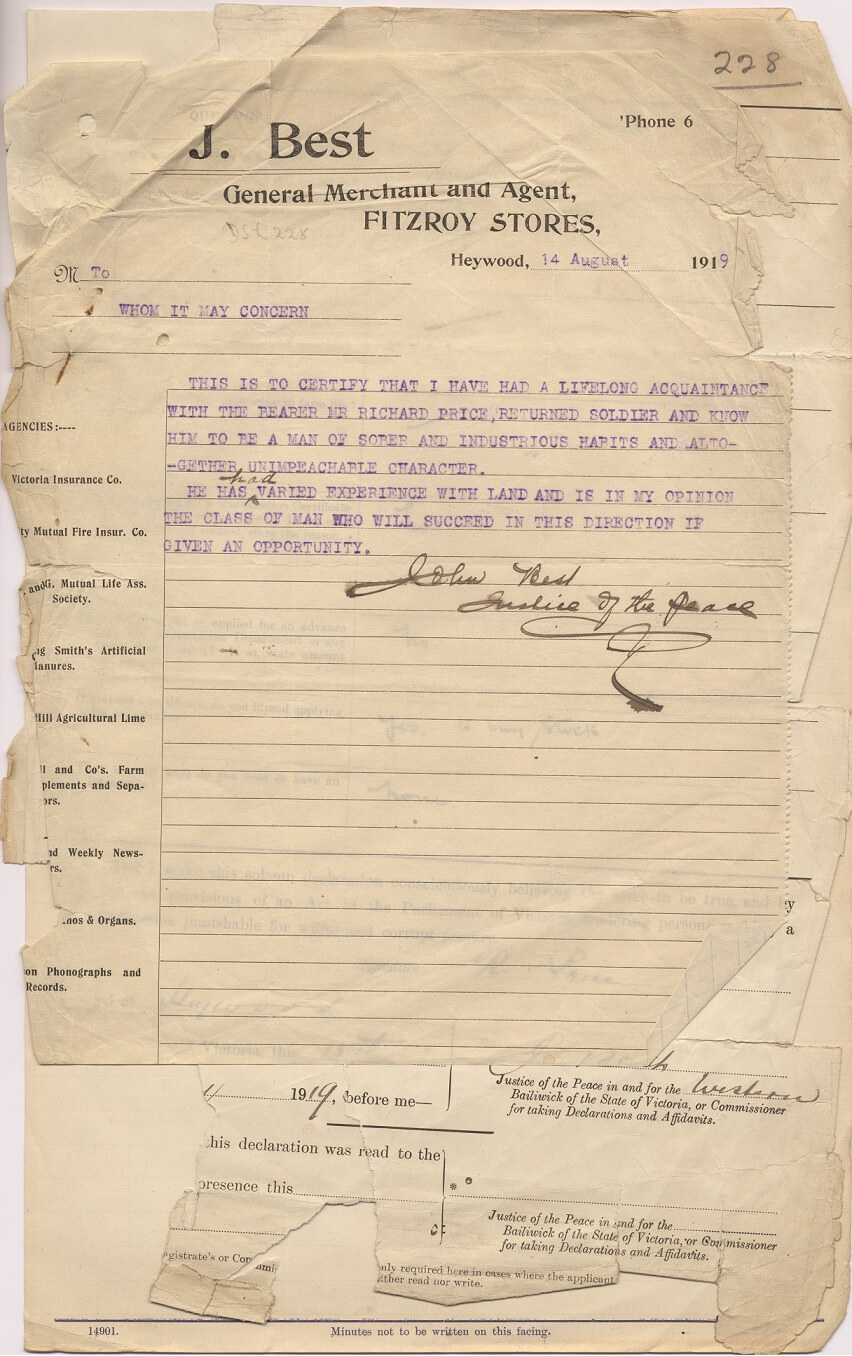

The applicant needed letters vouching for his farming experience, and a reference from his local Repatriation Committee. These were voluntary organisations established through the Commonwealth Government’s Repatriation Department to help servicemen readjust to civilian life.

Getting started

Applicants were not allowed to choose where they wanted to settle. Those who got through the application process successfully were allocated a block of land somewhere in their state and received a £500 advance (loan), which in later years was increased to £625. With this, they were expected to buy stock, farming equipment and seed, so that they could support themselves and their families. The land they received did not include a house or any other form of accommodation. It was up to the settlers to build their own homes.

When the new settler arrived on his or her block, the hard work of farming life began. Under the scheme, settlers were required to clear the land, fence their blocks, build stockyards, and get rid of weeds and pests, such as rabbits. Those who were allocated land on ‘dry’ blocks, such as in the Mallee, even had to provide their own water by building a dam.

To protect its investment, the state set in place an elaborate inspectorate, comprising district inspectors, area supervisors and a chief inspector. The inspectors’ duties were extensive. They had to supervise and advise settlers, collect and receive payments on behalf of the board, report upon and make recommendations on applications for advances to settlers, and advise settlers on buying stock and equipment.

Reproduced courtesy Public Record Office Victoria

VPRS 748/P0, unit 126

Applicants had to submit a ‘declaration’ to the Closer Settlement Board. This example is the declaration made by George Thomas Povey. He received a block in Paschendale, in south-west Victoria.

An applicant also had to submit references, vouching for his suitability for the scheme. These sometimes noted the applicant’s farming experience (although rarely in specific terms), but always his good character. Almost every reference to character noted the man’s sobriety. Rarely was an applicant rejected.

Here, Richard Price is referred to as ‘a man of sober and industrious habits and altogether impeccable character’.

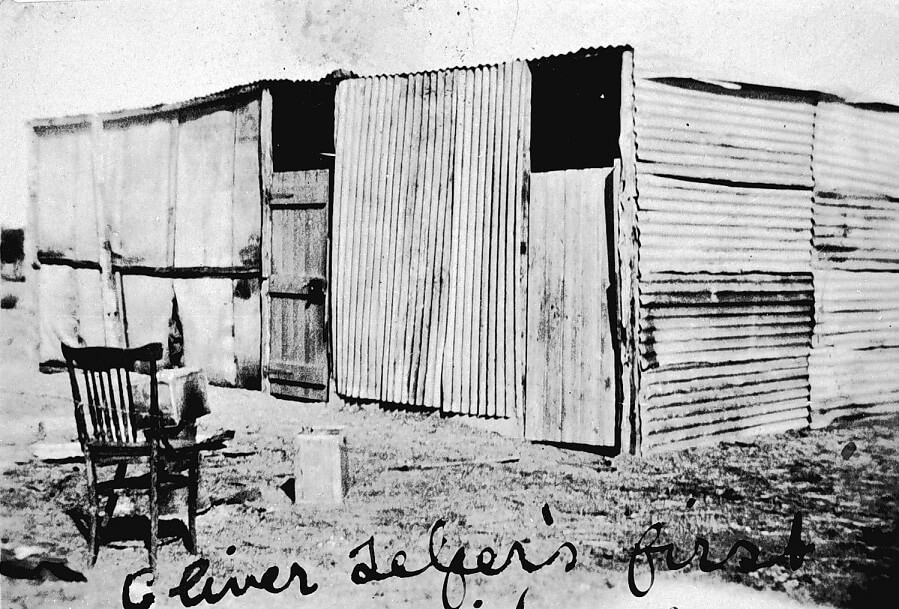

Until they could build something more permanent, settlers lived in makeshift quarters. These might be made of canvas over timber framing, or a small hut with corrugated iron walls and an earthen floor. Many soldier settlers lived in tents, sometimes for years.

A soldier settler’s ‘bag humpy’ at Nandaly, 1922

Reproduced courtesy Museums Victoria

A Soldier Settler’s first house, constructed of corrugated iron and hessian, 1922

Reproduced courtesy Museums Victoria

The ‘lottery’ for land

In the lottery for land, some soldier settlers were lucky enough to secure a good block. Some farms remained free from the ravages of pests and disease, but none could escape the fall in the price of farm commodities in the 1920s. ‘Many fine young Australians’, wrote the Age, ‘, were in such a position that, though they worked seven days a week, they could not earn one half the basic wage’.

Plummeting prices

Dairy farmers were hit earliest, in 1921, when most soldiers were still struggling to establish their farms. The price for butterfat fell by over 70 per cent that year. In 1925, when butterfat was selling for 1 shilling 3½ pence per pound [28 cents per kilogram], it was said to cost 2 shillings 3 pence per pound [40 cents per kilogram] to produce. Charles Schmidt at Boolarong wrote: ‘I have had a struggle making a start last year as you know there was scarcely a bare existence to be made out of dairying’. During the 1920s, prices for vegetables and fruit also plummeted. In 1924, for instance, potatoes were reported to be selling at half the cost of production.

The ‘exceptional low values for wool and lambs’, in settler Robert Wight’s words, brought many settlers to the brink of failure. William Toleman in the Western District had earned the local inspector’s praise through his hard work and improvements to the farm. But just as his farm became a paying proposition he was hit by the fall in wool prices. The local inspector was struck by the hopelessness of even the best settlers’ position:

Lessee has considerably improved the carrying capacity and the wool returns are less than when he was only carrying half the number of sheep. His arrears are becoming alarming … He is an excellent type of settler and does all his own work and his farm is a credit to him.

A dramatic drop in the price of wheat in 1931 was, for many, the final blow. For wheat growers in the Mallee, the plummeting price coincided cruelly with their first good harvest in four years. Many farms did not make enough profit to support the farmer and his family. If this was the case, settlers had to leave their own farms to earn money elsewhere, working as labourers or farm hands.

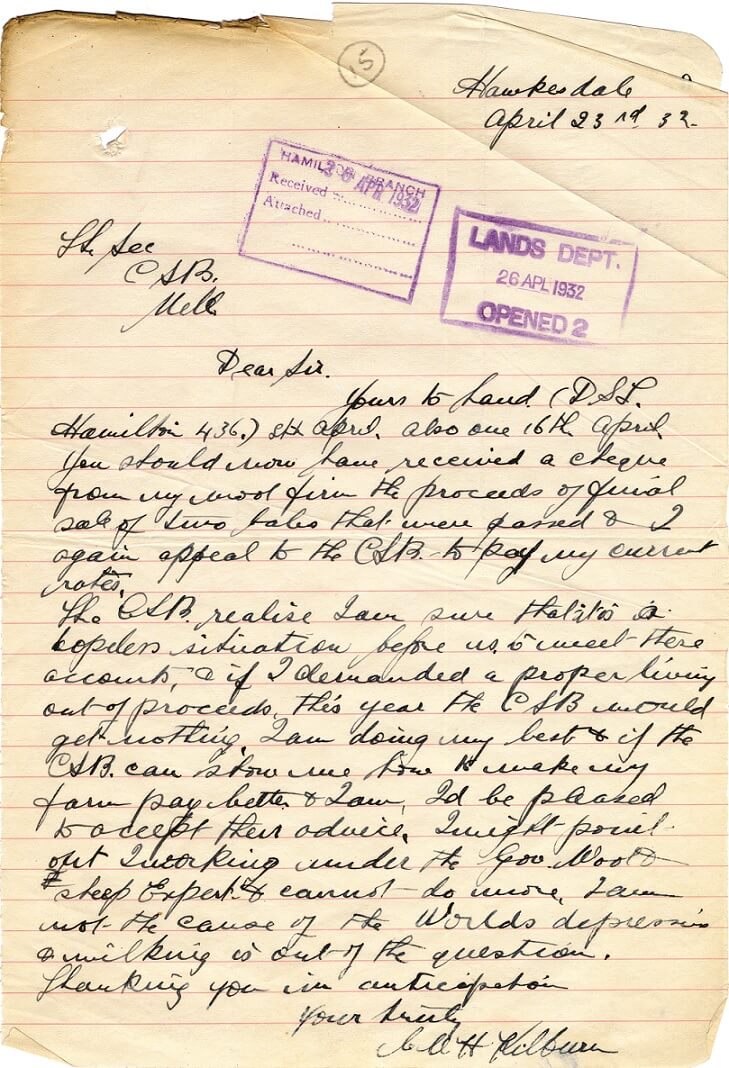

C.M.H. Kilburn, letter to Closer Settlement Board, 23 April 1932

Reproduced courtesy Public Record Office Victoria

VPRS 748/P0, unit 88

According to the Closer Settlement Board, C.M.H. Kilburn of Hawkesdale was transformed from a ‘very good farmer’ into a ‘hopeless case’ by the fall in wool prices. Kilburn, describing the pressures he was under, remarked: ‘I [am] working under the Government Wool and Sheep Expert and cannot do more. I am not the cause of the World’s depression’.

Success, or failure?

In 1925 a Royal Commission was established to inquire into the workings of the Soldier Settlement Scheme. The report found several major defects in the scheme and noted: ‘it is surprising not that there have been mistakes, but that there were so few’. Four main faults were identified — the selection of inexperienced soldiers, their lack of capital, the small size of blocks allocated, and the low prices farmers received for agricultural products.

Left in debt

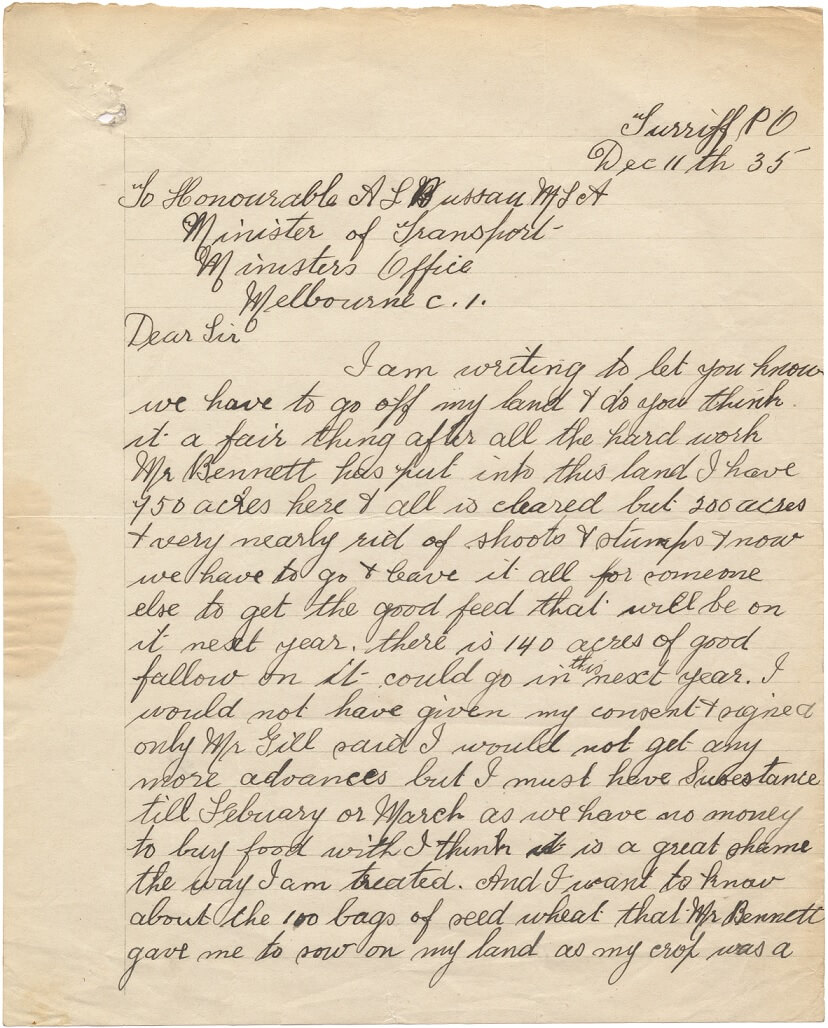

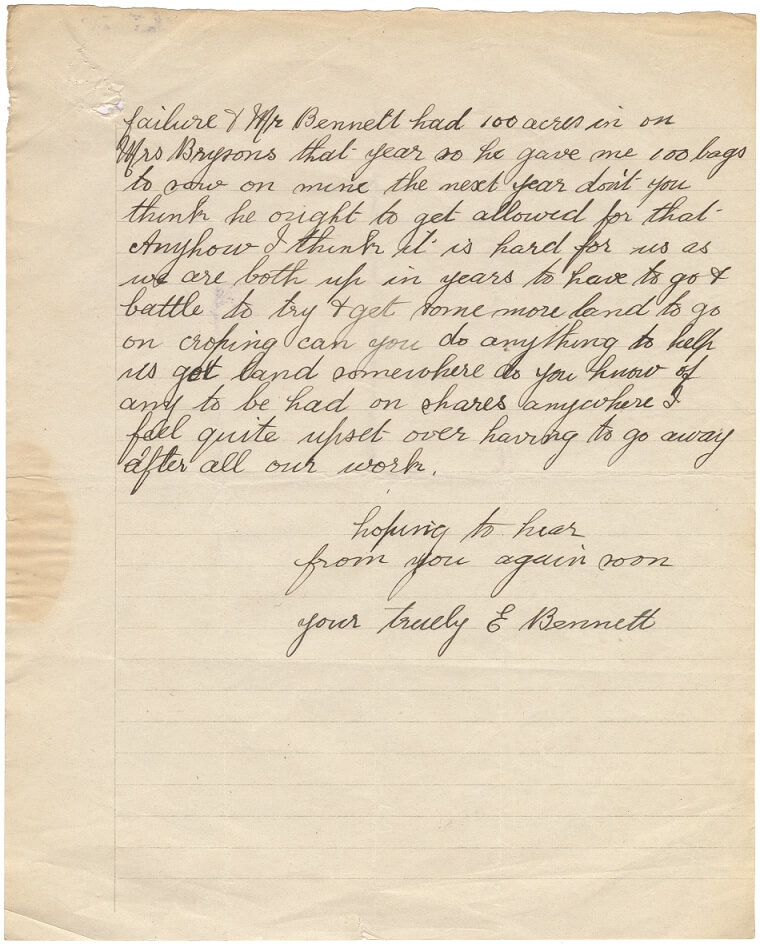

By 1926 some 3,000 soldier settlers had walked off their properties, or had been removed due to their inability to repay their debts. Ellen and Frank Bennett, settlers near Turriff in the Mallee, had to ask the government for financial help soon after they took up their land. They needed to buy horse feed so that they could begin clearing the dense Mallee scrub. Soon after this they requested ‘sustenance’ payments, as they had ‘nothing to live on’. By 1935 they were still living in a house with hessian ceilings and walls. The board acknowledged that the Bennetts’ position was hopeless, and they left the land.

Leslie Summer’s story is another sad, but not isolated, indictment of the scheme. Arriving in 1920 with £70, he and his family lived in a shed on their property at Woorarra in Gippsland. By 1922 he was pleading for money: ‘Wire me at once … two shillings left’. Needing more and more financial loans from the government, and accruing interest, Summer was caught in a cycle of debt he could not repay. When the local shop refused to provide him with food and supplies on credit he was left with two options — leave the farm, or starve.

Some success stories

Not all soldier settlements ended in failure. Many settlers remained on the land, raising their children. John Wright Mills and his wife, Ruby, settled near Katamatite in 1920. As a farmer, John had the advantage of being a local in the area. Within five years, the Mills were seeking to buy a neighbouring block. In 1951, John and Ruby Mills presented the Closer Settlement Board with a cheque for £3,374, to gain freehold on their 640 acres (259 hectares).

Today, a century after the establishment of the scheme, descendants of soldier settlers are still on the land. The experiences of World War I soldier settlers paved the way for the next generation of servicemen, who returned from World War II. These soldier settlers benefited from the important lessons learnt from the previous scheme. Applicants were carefully selected, given accommodation on their blocks, awarded a basic living wage and given extensive agricultural training. Better support for physical and mental health was also provided. It helped that world prices for agricultural products boomed in the post-war period.

Ellen Bennett, letter to the Closer Settlement Board, 11 December 1935

Reproduced courtesy Public Record Office Victoria

VPRS 749/P0, unit 18

‘… we have no money to buy food with … it is a great shame the way I am treated’.

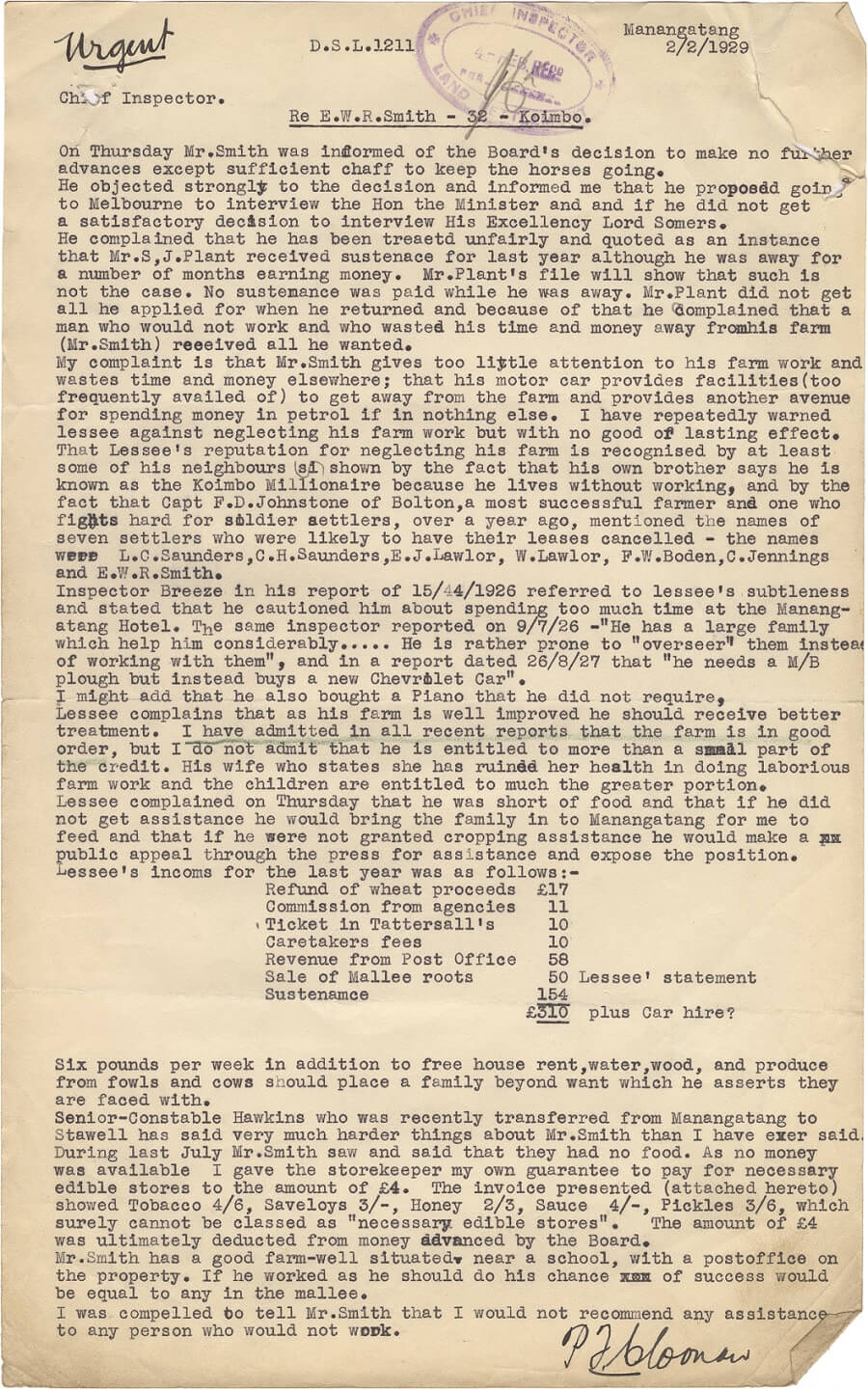

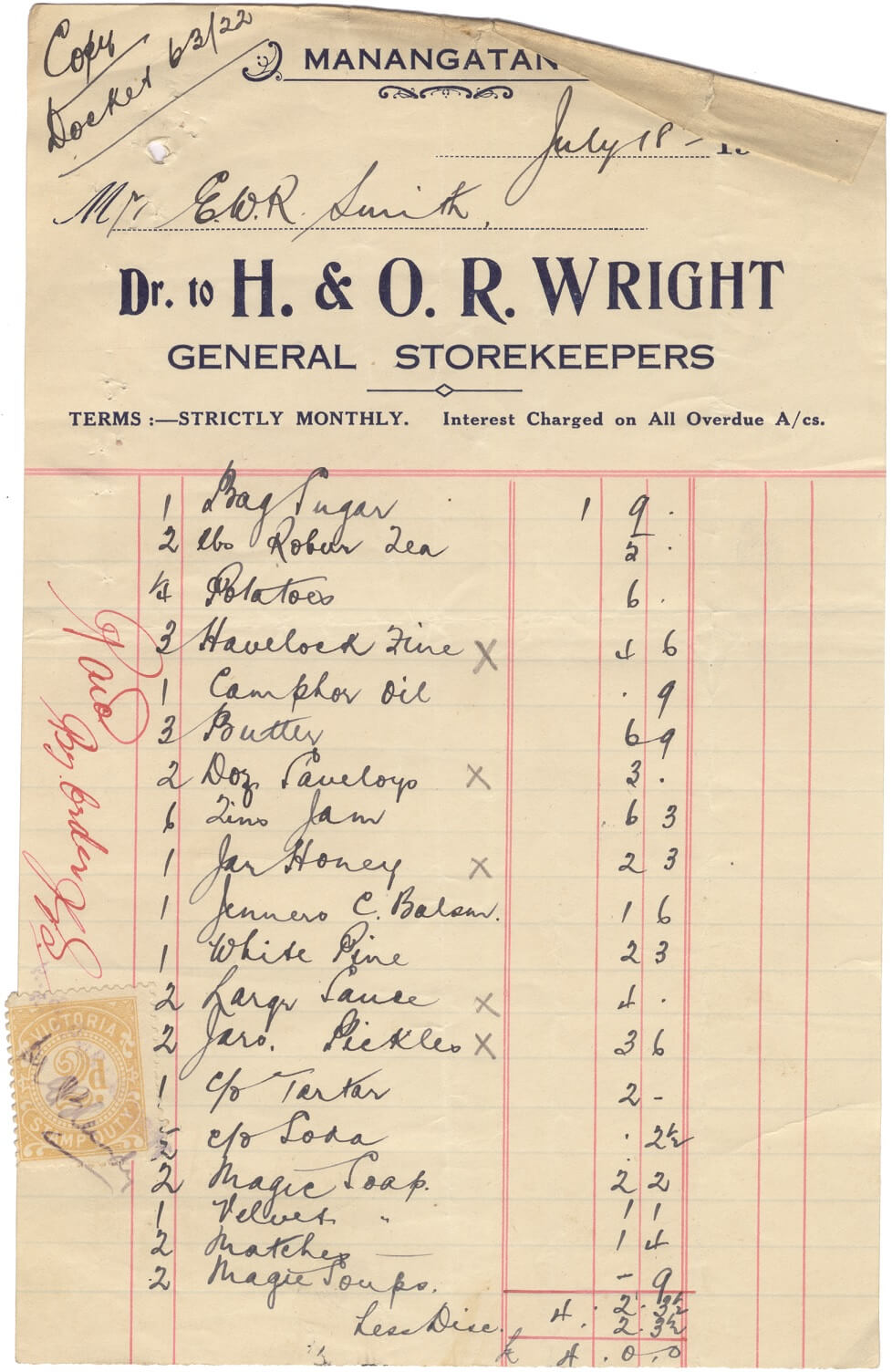

Inspector’s report, 2 February 1929, and grocery bill

Reproduced courtesy Public Record Office Victoria

VPRS 749/P0, unit 296

Struggling to make a living was a harsh and often degrading existence. Soldier settlers who received assistance were required to produce lists of grocery purchases, which were checked by Closer Settlement Board officials to ensure that only bare necessities were bought. The scrutiny of one settler’s grocery account prompted the comment: ‘his groceries included tobacco, saveloys, honey, sauce, pickles, which surely cannot be classed as “necessary edible stores”’.

Setting up a home

Some families were able to build a home with their own savings, or by using money loaned to them by the Closer Settlement Board. For these families, life was relatively comfortable.

Other families were not so lucky. The burden of loan repayments, poor crop yields or a lack of savings forced many settlers to live in tents, or in homes made of canvas or hessian bags, scrap tin, or wattle and daub. These ‘bag humpies’ were far from weatherproof and were a difficult setting in which to rear children. One settler at Paschendale in the Western District lived with his family in a stable. Another family lived during their first few years under manure bags. Settler Leslie Summer lived with his wife, Dorothy, and their three little girls in conditions like these. In 1922, Leslie begged the board for a house: ‘we are in a very bad way, living in a hut and the rain from the east goes right through …’

Settler women

The wives of soldier settlers had to cope with isolation, poverty and difficult living conditions. They shouldered a large portion of farm work and carried full responsibility for housework and child-rearing. Women were considered vital helpmates, assisting their husbands in the fields or cow sheds. On dairy farms women woke at dawn to milk the cows: on wheat and fruit farms, women worked the same hours of physical labour as their husbands — often longer at harvest time, when they also had to cook meals for all the farm workers.

Child-rearing under difficult living conditions had to be balanced with farm work. In 1926 one woman wrote to the Countryman newspaper, declaring, ‘I have milked with a baby in the pram and a toddler in a little wire netting yard … then bumped the pram home with the two in it and a bucket in each hand!’

Settler women were helped by initiatives such as the Better Farming Train, which featured ‘lady demonstrators in household affairs to assist the farmer’s wife’. One visit by the train attracted nearly 20,000 women, and featured lectures on ‘baby welfare’ and ‘mothercraft’ by infant health nurse Sister Muriel Peck. Events such as these helped isolated women make community connections. The women banded together, forming baby health centres and mothers’ groups, and assisting one another during harvest times.

Children on the farm

On many blocks, the work of the youngest family members was vital. Children contributed regularly to the day-to-day functioning of the farm, allowing settlers to save on labour costs. Leslie Kirby, a Mallee settler, attributed his block’s success to ‘the labour of my wife and two sons’. Compulsory schooling was a burden for many families, taking the children away from the fields. Organisations such as the Victorian Farmers’ Union and the Australian Housewives Association protested the ‘slavery of little children’ on farms. At the same, the Closer Settlement Board urged settlers to use the cost-saving labour of their wives and children.

Children were a vital part of the farm workforce. However, it took some years for children to become useful around the farm: until then, children were a costly addition to a household.

Farming was a family affair. On dairy farms, milking was often the work of the women and children — even toddlers accompanied their mothers to the cowsheds, learning from an early age how to help.

Sister Muriel Peck giving a mothercraft demonstration on the Better Farming Train

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

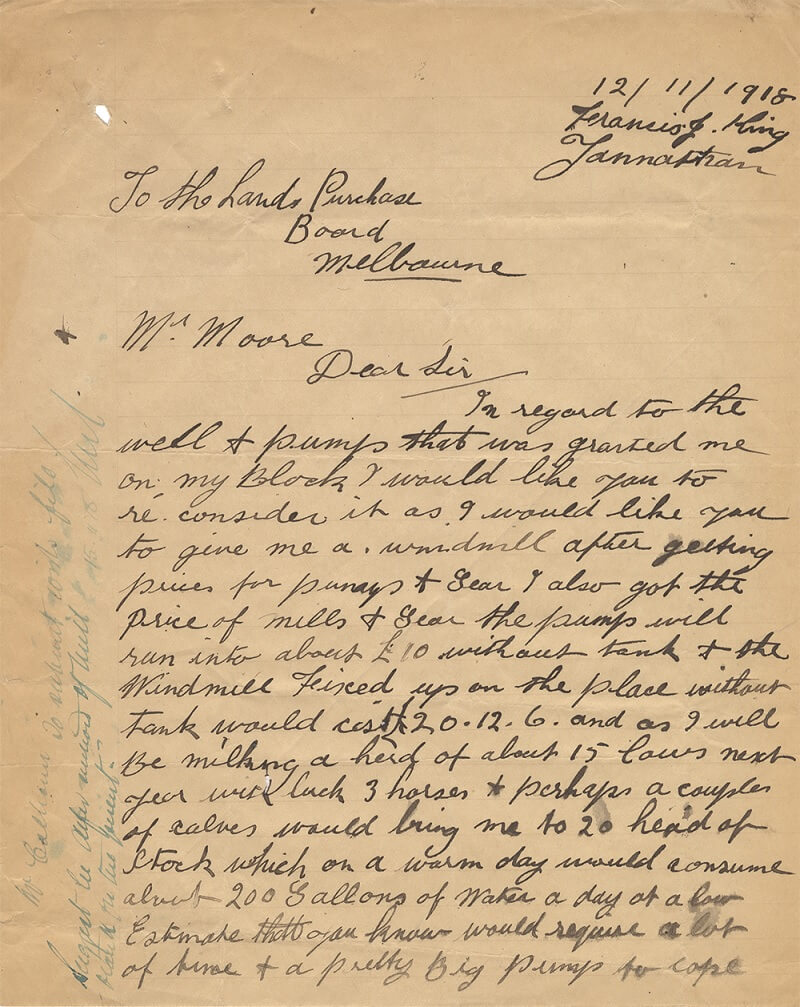

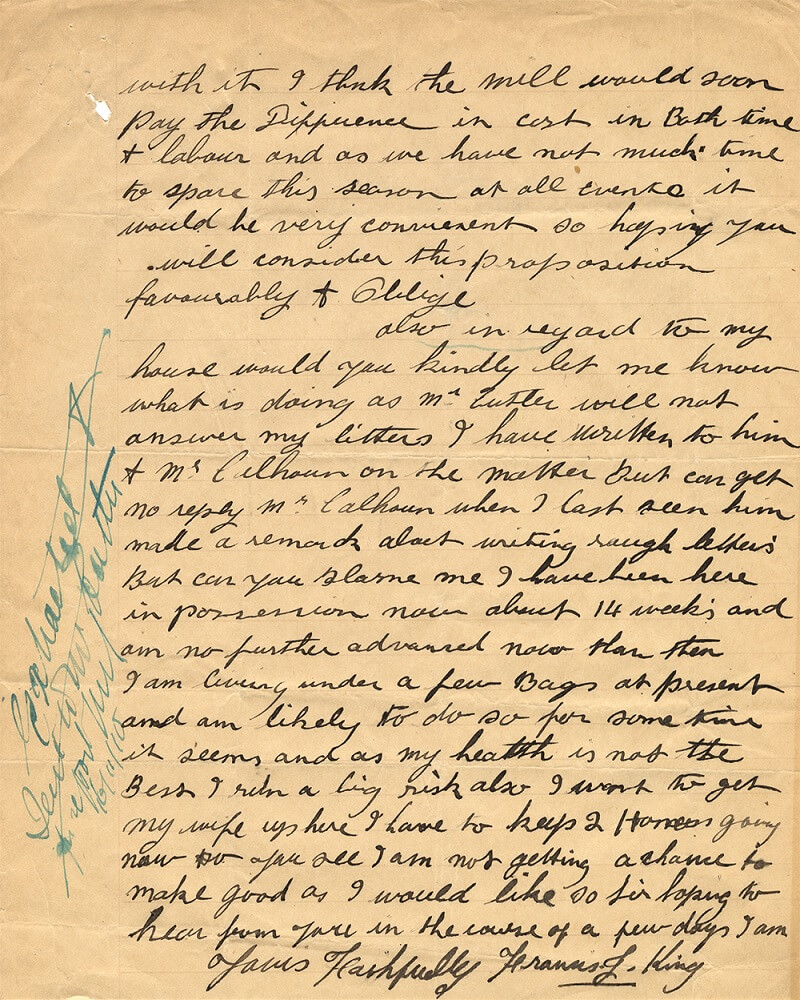

Francis King, letter to Closer Settlement Board, 26 October 1918

Reproduced courtesy Public Record Office Victoria

VPRS 10381/P0, unit 7

Francis King at Yanathan lived ‘under a few bags’. ‘My living conditions is awful’, he wrote, ‘When it rains I get everything wet including bed and clothes.’ While King was living under bags, his wife remained in town – a separation that became permanent.

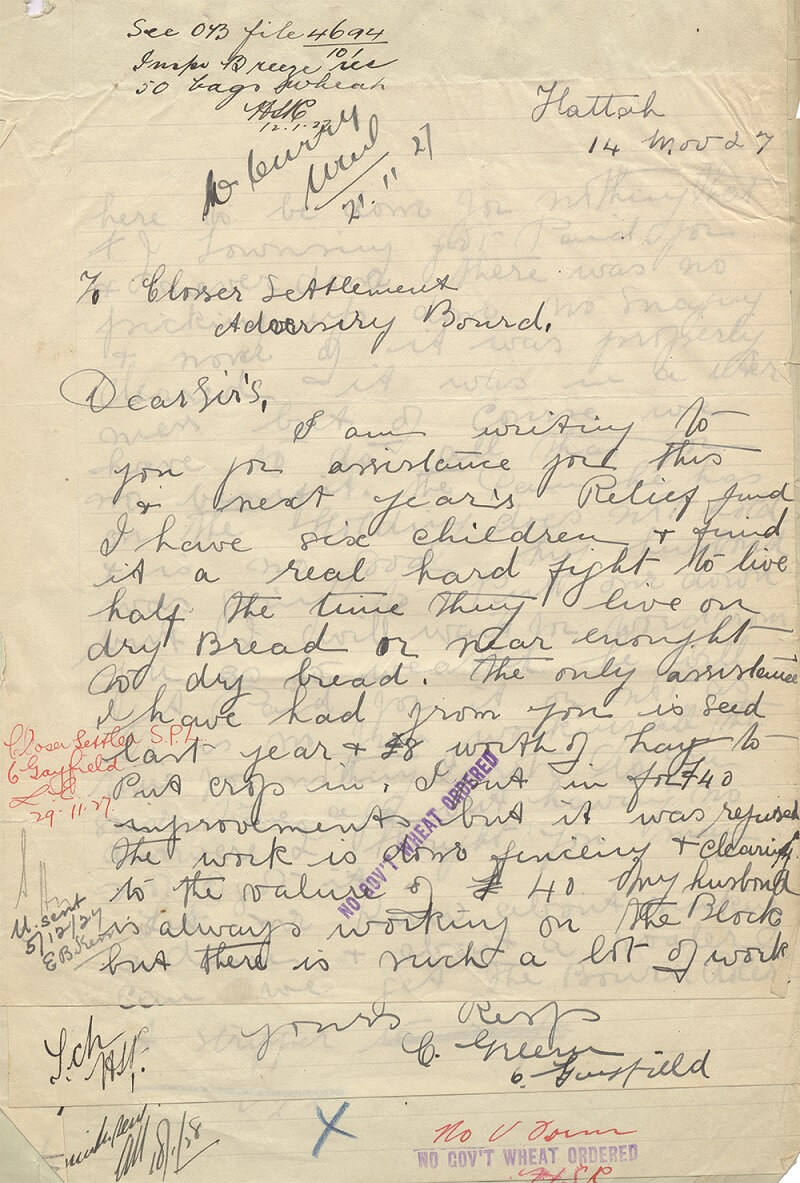

Reproduced courtesy Public Record Office Victoria

VPRS 749/P0, unit 123

In 1927 Mrs C. Green of Hattah wrote to the Closer Settlement Board about her situation, raising a family of six children: ‘A real hard fight to live half the time. They live on dry bread or near enough to dry bread’.

Health and disability

We must realise that these men come back with less strength than they had when they went away, that they are restless, that their nerves are shattered.

Henry Angus, Member Legislative Assembly, 1917

In World War I about 123,000 Australian servicemen were seriously wounded at least once, 16,000 were gassed and 1600 were diagnosed as being ‘shell-shocked’. Out of the approximately 270,000 returnees, 73,000 were already on pensions by 1919 and that number had grown to 90,000 by 1920.

Unable to work the land

The horrors of frontline service left many men with a range of physical disabilities, including loss of limbs, chronic pain and breathing difficulties. Many soldiers also suffered from long-term, but poorly understood, mental illness. Symptoms of ‘shell shock’ (today known as post-traumatic stress disorder) included delirium, delusions, hallucinations and acute dementia. Returned soldiers were reported to be especially susceptible to alcohol addiction, insomnia and aggressive behaviour.

Many of the soldiers were accepted into the Soldier Settlement Scheme despite having physical disabilities, injuries and chronic pain that made them wholly unsuited to farming and manual labour. Michael Kelly of Korongah estate near Warrnambool was 24 years of age when he received his farm. He had been wounded twice and gassed. Letters to the Closer Settlement Board from his wife, Rubena, provide an insight into the mental anguish many of these men and their families experienced as result of their war injuries:

I feel sorry for the returned soldiers … I think the soldiers are to be pitied, there must be something wrong somewhere or they would not be like they are.

Mr Kelly … is suffering a lot with his nerves … and is not fit for work. I have to battle along on my own and it is terrible hard …

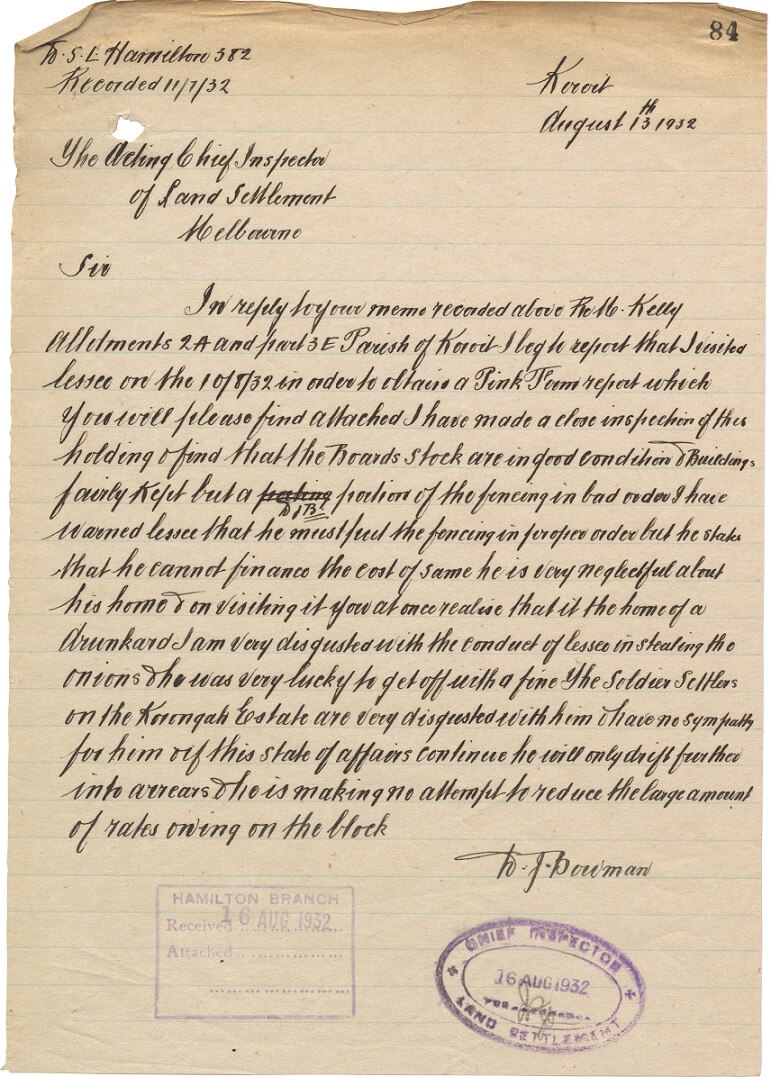

Little was known about the continuing psychological effects of trench warfare. An inspector, reporting in 1930 on Kelly’s mental state and management of his farm, showed little understanding or empathy for his situation:

He is very neglectful about his home, on visiting it you at once realize it is the home of a drunkard … The soldier settlers on the Korongah estate are very disgusted with him and have no sympathy for him.

Chinese-Australian Thomas ‘Bill’ William Ah Chow served on the Western Front, where he was shot twice and gassed. Granted a settlement block in Bruthen in 1923, he gave it up in 1926, ‘because… on the block I still had pains and shortness of breath, found it very hard to breathe, had to sit down for a while’. In 1923, James Inman gave up his block because the repetitive action of using a plough aggravated his ‘burnt hands caused by an explosion’ during the war. Some settlers were so severely wounded they collapsed and died shortly after taking up their blocks.

The 1925 Report of the Royal Commission on Soldier Settlement would identify injuries and disabilities of soldier settlers as one of the critical factors contributing to the high proportion of failed holdings.

Inspector’s report on Michael Kelly

Reproduced courtesy Public Record Office Victoria

VPRS 748/P0, unit 87

‘… on visiting it you at once realize it is the home of a drunkard …’

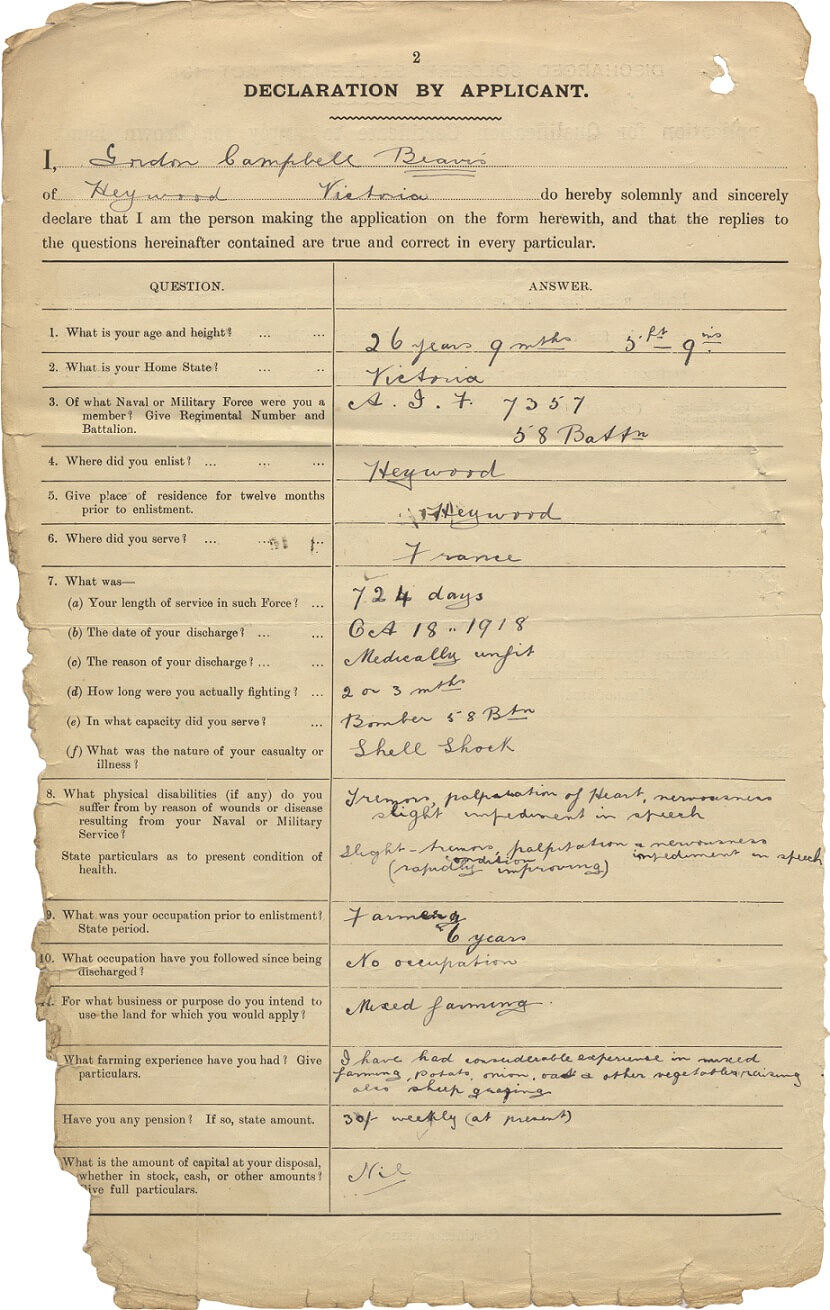

Reproduced courtesy Public Record Office Victoria

VPRS 748/P0, unit 9

Gordon Beavis was one example of a settler whose poor health was ignored by the Closer Settlement Board. In his application for land, Beavis described himself as suffering from ‘Tremors, palpitations of heart, nervousness, slight impediment of speech’. Despite this, he received a block near Heywood in Victoria’s Western District.

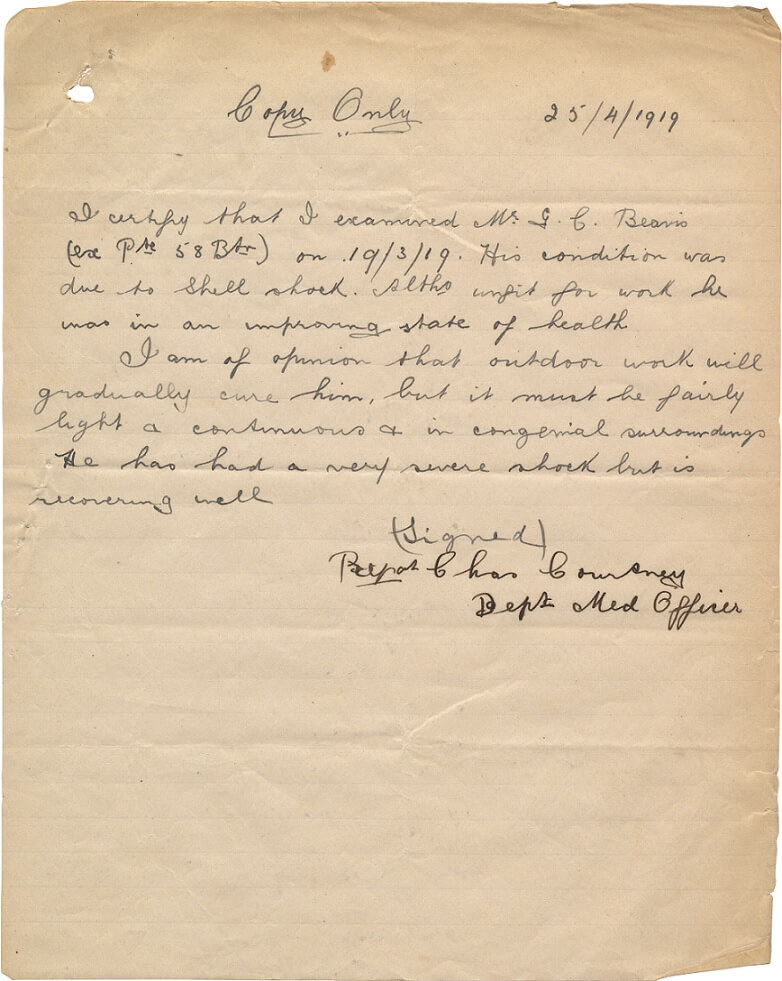

Reproduced courtesy Public Record Office Victoria

VPRS 748/P0, unit 9

Life on the land was seen as therapeutic. The doctor’s report accompanying Gordon Beavis’ application stated: ‘Altho unfit for work, he is in an improving state of health. I am of the opinion that outdoors work will gradually cure him …’ Beavis was placed on a dairy farm, where the work was not ‘light’. By the early 1930s, he was described as a ‘failure’, with no chance of success.

Women soldier settlers

Like Australia’s war pensions scheme, soldier settlement was designed to benefit not only returned servicemen, but also the dependents of soldiers who had been killed in the war. A deceased soldier’s widow, mother or child was eligible to take up land on the same terms as the returned serviceman. Nurses could also apply for land through the scheme. At least nine Victorian nurses were successful in their applications to be granted a block.

To be a female settler took enormous courage. Women took to their blocks with determination, defying social conventions and expectations. Although they did not always win the support of the Closer Settlement Board, some of these resilient women earned the high regard of their communities, who recognised and applauded their hard work and dedication.

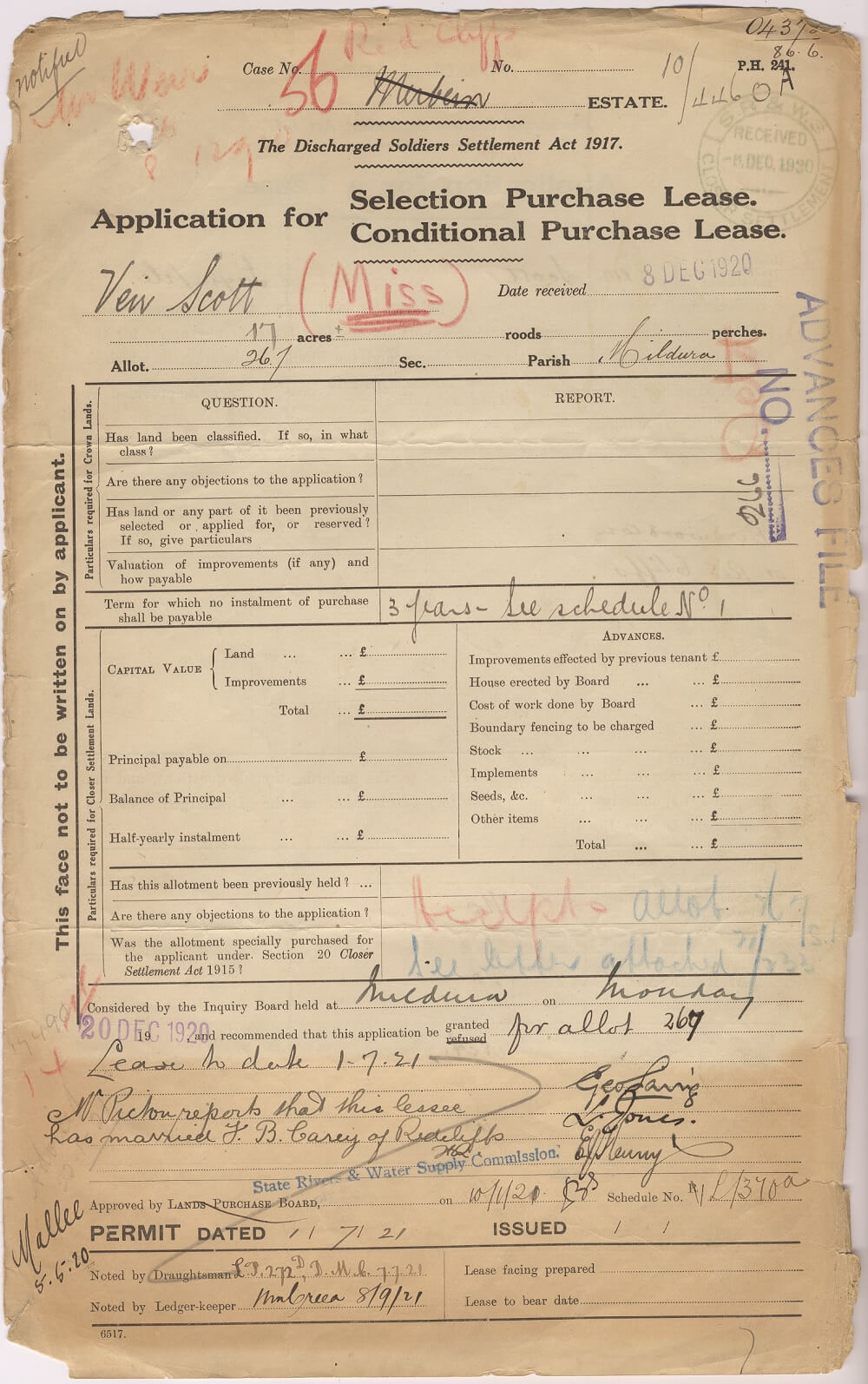

Sister Nellie Veir Scott

Of the nine Victorian nurses granted land under the scheme, just one was still on her farm at the time of her death in 1973 — Nellie Veir Scott, of Red Cliffs, near Mildura. Veir Scott (as she preferred to be called) had trained as a nurse at the Broken Hill and District Hospital, where she graduated in 1913. In 1915, aged 25 years, she signed up with the Australian Army Nursing Service. Her first posting was at the No. 15 General Hospital in Alexandria, Egypt. In April 1916 she was transferred to the hospital ship Valdivia, on which the wounded were treated and transported between Salonica, Malta and Lemnos.

In May 1919 Scott was discharged and went home to Australia. In 1921, when the Red Cliffs Soldier Settlement was opened up, she was the only woman among 708 settlers. In her application she wrote: ‘I have made the fullest inquiries before submitting it to you, and it seems to be quite in order, as returned sisters are entitled to any privileges conceded to returned men’. She included several references, one of which stated: ‘I consider her quite capable of managing a block and doing a great portion of the work herself’.

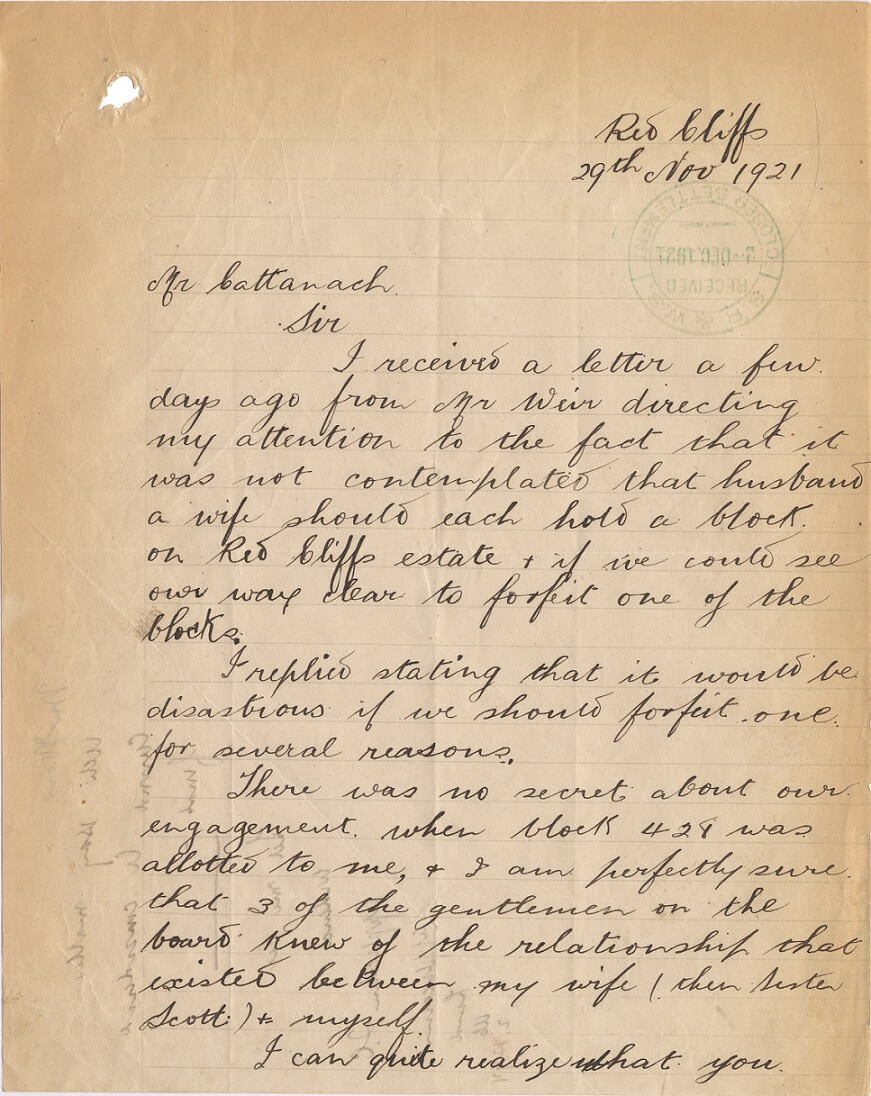

In 1921 Veir Scott married another settler, Frank Carey, who also had a block at Red Cliffs. The board wrote to Scott, requesting that, as she was now married, she or her husband ‘withdraw from one allotment’ and ‘surrender your claim’. Frank Carey replied that to do so ‘would be disastrous … we only desire to have the right to marry whom and when we wish … surely they would not deny one returned sister … it appears we can live on fresh air’.

Frank and Veir kept both blocks and, after her husband’s death in 1939, Veir managed the two properties. She was held in high esteem, was active in many local organisations and charities and was respected as a horticulturalist. ‘In those days men didn’t like taking orders from women’, says her daughter, Coral, ‘But the men that worked for mum respected her. She never asked them to do a job that she couldn’t. She pruned and did all that work too. And she owned her block up until her death, which I think is rather special’.

Veir Scott’s application for land through the Soldier Settlement Scheme. The red pencil perhaps notes surprise at her sex.

Reproduced courtesy Public Record Office Victoria

VPRS 5714/P0, unit 1910, file 2455/12

Frank Carey, letter to the Closer Settlement Board, 29 November 1921

Reproduced courtesy Public Record Office Victoria

VPRS 5714/P0, unit 1910

‘… surely they would not deny one returned sister …’

First Nations Soldier Settlers

Although initially excluded from enlistment, considered not ‘substantially of European descent’, more than 100 eligible Aboriginal Victorians ‘answered the call’ during the First World War. Men from across Victoria, including those on missions and reserves, left their families and livelihoods to fight for their country.

Very few Aboriginal soldiers are known to have been granted a Soldier Settlement holding. We do, however, know of two successful applicants — Private Percy Pepper of Gippsland and Private George Winter McDonald of Lake Condah.

Percy Pepper

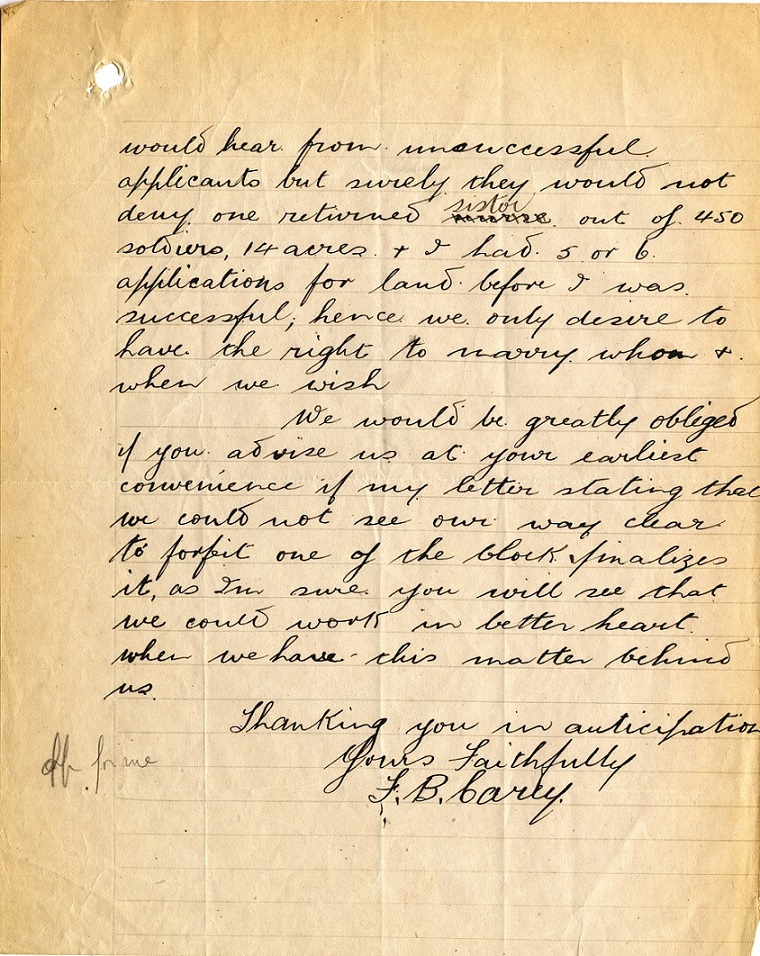

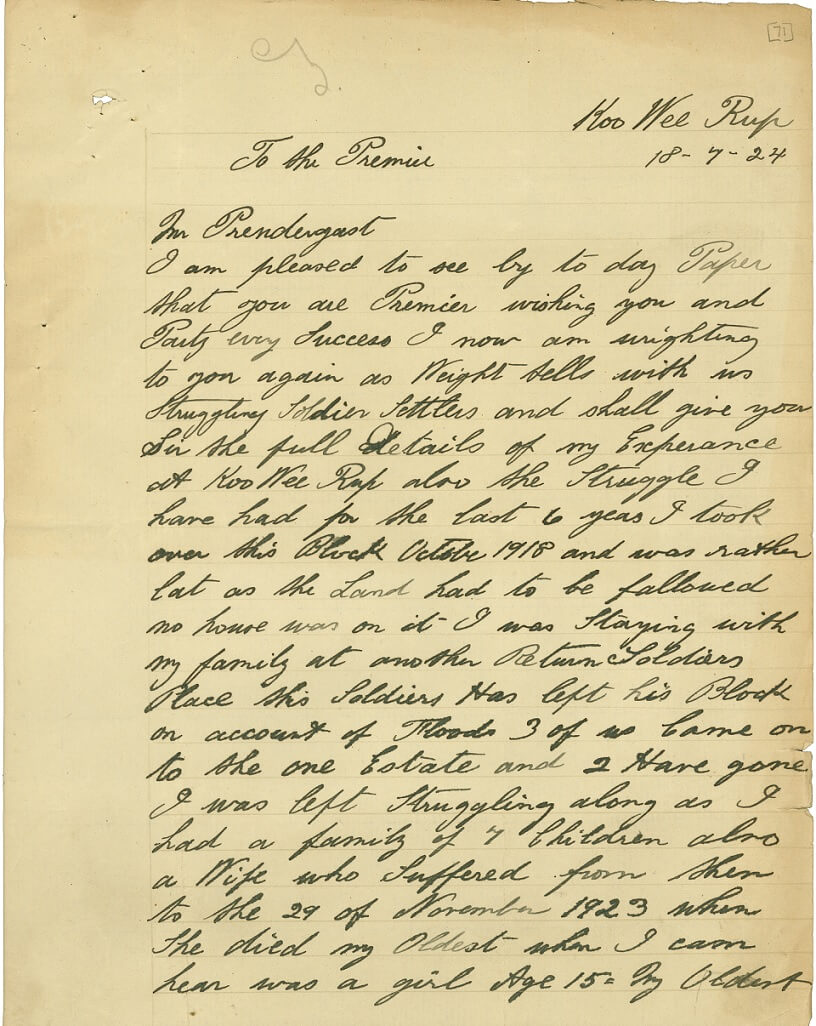

In September 1918 Percy Pepper acquired a qualification certificate and, following recommendation from the local land board, was given a block of land on lease. The land was at Koo-Wee-Rup, south-east of Melbourne. The area had previously been a large swamp, much of which had been reclaimed and drained for farming.

Percy, his wife, Lucy and their children moved to Koo-Wee-Rup, living in a small house on the block. Under the conditions of the Soldier Settlement Scheme, they did not have to make repayments on the land for the first three years.

Pepper struggled to make the farm viable. He was crippled by bad weather and crop failure. In June 1920 Percy wrote to the local Repatriation Committee:

I am in a fix … I have had a run of bad Luck … sickness in the family has hit me very hard as well as not to good a Potato Crop.

Like many other servicemen, Pepper was unable to succeed on his soldier settlement block. Getting further in debt, with pressure mounting from the Closer Settlement Board, he wrote to George Prendergast, the leader of the opposition (and, from July to November 1924, premier of Victoria) to plead for special consideration and more time to make the farm viable. But on 9 May 1924 the lease was declared void, for non-payment of instalments. Having lost his farm, Percy moved to Melbourne and, for the rest of his life, lived in the inner northern suburbs of Fitzroy and Carlton.

Percy Pepper, letter to premier of Victoria, 18 July 1924

Reproduced courtesy Public Record Office Victoria

VPRS 5714/P0, unit 2508

Percy Pepper wrote to the newly elected premier of Victoria, George Prendergast, asking for help to stop the sale of his soldier settlement block.

George Winter McDonald

In January 1920 McDonald applied successfully for a solider settlement block, in the Corangamite estate. In his application he stated that he would use his land for mixed farming. Referee George Hutchings wrote: ‘he is a good horseman and a good milker and understands farm work generally’.

McDonald’s time on the land was ill-fated. He faced the same problems as many of his fellow soldier settlers, including poor-quality but overvalued land, which could barely grow grass. He also battled his physical disability and alcoholism. McDonald’s lease was cancelled in 1923 and the land divided up among the adjoining blocks. He found employment as a farm hand at Condah.

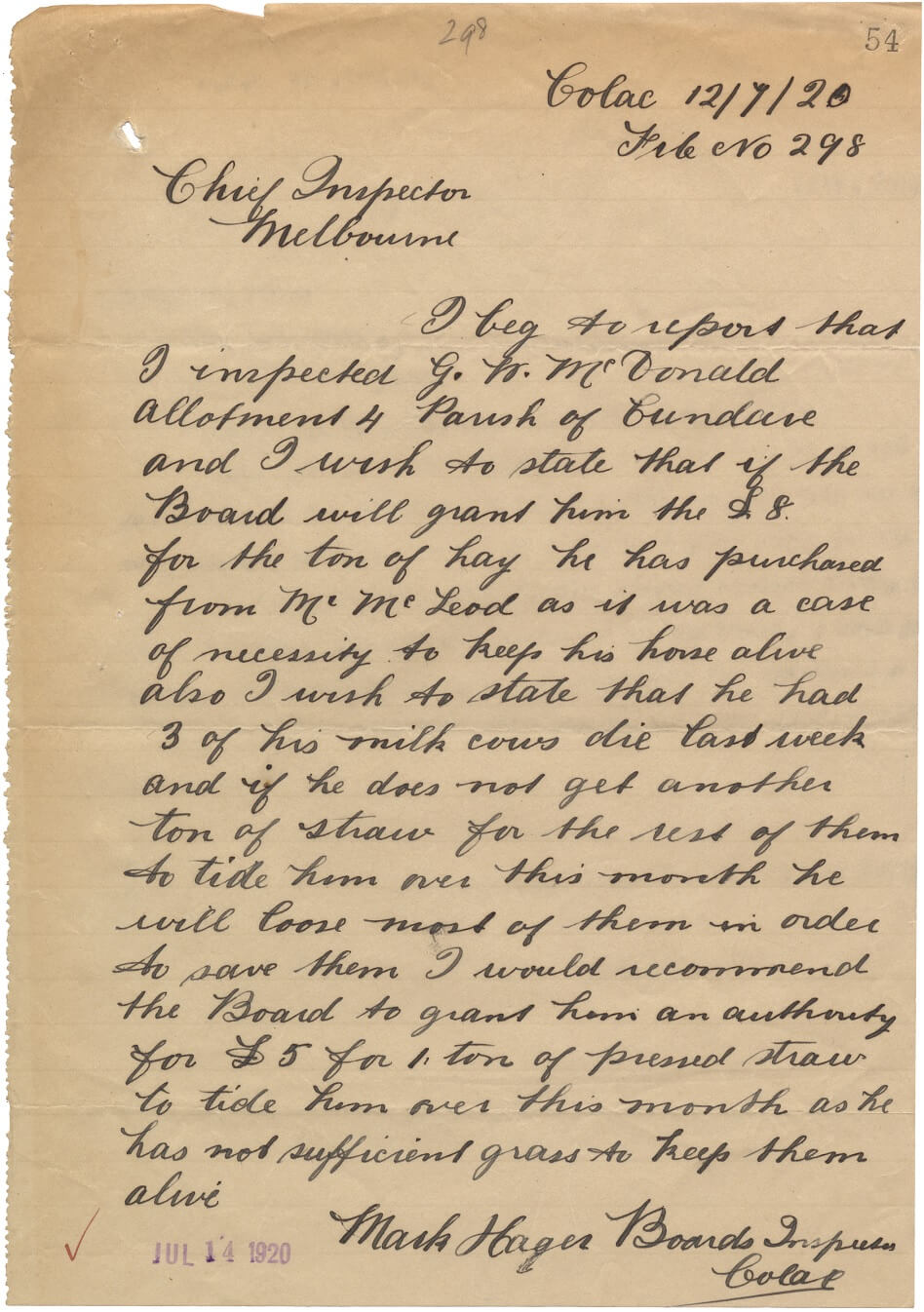

Mark Hager, Closer Settlement Board inspector in Colac, letter requesting assistance for George Winter McDonald, July 1920

Reproduced courtesy Public Record Office Victoria

VPRS 746/P0, unit 185

Within months of obtaining his block, George McDonald had become desperate. He was unable to feed his livestock and needed help from the board to keep his horses alive. Three of his dairy cows had died that week.

A sense of community

As well as building farms, soldier settlers built communities. In previously settled areas, the Western District and the Goulburn Valley irrigation district for instance, the government bought estates for soldier settlers where towns and villages already existed. In new areas, most importantly the Mallee, soldier settlement encouraged the establishment of small towns and villages.

Town life

Settlers came to town regularly, sometimes two or three times a week, to buy goods, attend meetings, meet government officials and take part in sporting events or public entertainment. For soldier settlers, meetings of the Returned Soldiers Association were a particularly important outing. For women, meetings of the Country Women’s Association provided companionship. Wives often went into town to collect mail and buy groceries. In 1923 Maud Lane, the wife of Henry Lane, travelled at least once a week from their Mallee selection in Wagant to the small township of Kulwin for stores.

Country life

On the farms, a deeper sense of community developed. Here, neighbours were essential to the routine of daily work and entertainment. At Kulwin, 253 miles (407 kilometres) north-west of Melbourne, William Henry Lane took up a Mallee block of 750 acres (303 hectares) in 1923. The Closer Settlement Board made cash advances to Lane to employ labour, but he also relied heavily on his neighbours. And they relied on him. Every harvest, Lane found time to help his neighbours strip, bag and sew their wheat. Machinery was regularly shared and, at planting and harvest times, combine drills, reaper binders, and harvesters moved between properties. William Lane’s diary shows that in the 1920s he regularly visited neighbours, and they dropped by his block several times a week.

Neighbours were also critical in times of crisis, such as injury or sickness. When Maud Lane was struck down with kidney disease in January 1929, a neighbouring farmer’s wife drove her to Ouyen hospital.

The Ladies’ Committee of the Baby Health Centre at Red Cliffs, near Mildura, 1926

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

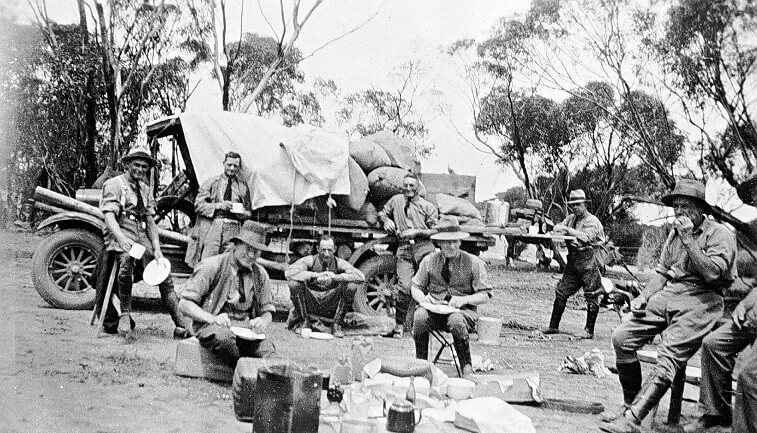

Returned Soldier Settlers from the Mallee having a roadside meal, Wemen, Victoria, c.1930

Reproduced courtesy Museums Victoria

Author: Ann Wilcox

Next: On the Land: The Better Farming Train

Next Topic- On the Street

Sources / Recommended reading

Institutions / online sources

Australian War Memorial

Museum Victoria

National Library of Australia

Public Record Office Victoria, https://soldiersettlement.prov.vic.gov.au/; https://prov.vic.gov.au/explore-collection/explore-topic/researching-land-and-property/soldier-settlement-scheme

Victorian Parliamentary Library

Secondary sources

Jessie Suzanne Matheson, Countryminded Conforming Femininity: A Cultural History of Rural Womanhood in Australia, 1920-1997, Ph.D. thesis, School of Historical and Philosophical Studies, The University of Melbourne, 2021

Kate Darian-Smith, ‘Domestic Spaces and School Places: vocational education and gender in modern Australia’, in Designing Schools: Space, Place and Pedagogy, Abingdon, Oxon; New York, NY, Routledge, and imprint of the Taylor & Frances Group, 2017

Katie Holmes and Kylie Mirmohamadi, ‘All Aboard for Modernity: The Better Farming Train’, Agricultural History, Vol. 91, No. 2, Spring 2017, pp. 215-238

Ken Frost, Soldier settlement after World War One in south western Victoria, Ph.D. thesis, School of Social and International Studies, Deakin University, 2002

Jessie Suzanne Matheson, Countryminded Conforming Femininity: A Cultural History of Rural Womanhood in Australia, 1920-1997, Ph.D. thesis, School of Historical and Philosophical Studies, The University of Melbourne, 2021

Marilyn Lake, The limits of hope: soldier settlement in Victoria, 1915-38, Melbourne, Oxford University Press, 1987

Monica Keneley, Land of hope: soldier settlement in Western District of Victoria, 1918-1930, Geelong, Deakin University, 1999

Report of the Royal Commission on Soldier Settlement: together with appendices, Melbourne, H.J. Green, Government Printer, 1925

Soldier settlement: the soldiers’ heavy incubus under fusion government: the boom-and-burst policy, authorised by D.L. McNamara, Melbourne, Australian Labor Party Victorian Branch, 1926

Old Treasury Building would like to thank the following people for their time and contributions:

Charles Fahey

Marilyn Lake

Marina Larson

Monica Keneley