Until the 1960s many residents of Melbourne had their bread, milk, vegetables and meat home-delivered by horse and cart. Perishable items were delivered on a daily basis or sold door to door. The Chinese greengrocer, or ‘costermonger’ was a familiar sight in the suburbs selling vegetables, although many homes had fruit trees in their gardens. Ice-carters made deliveries too, with regular supplies from the late 1850s. Historian, Beverly Kingston, notes that in the poorer suburbs, meals often depended on which street vendor had called — the rabbito, the ‘watercress man’ or fish-seller: ‘There was the ice underneath and the teatowel over it. It was all very nice and clean. They’d buy it at the fishmarket and they’d come round about nine o’clock’.

Shopping for food and domestic products was very different. Housewives had standing orders and, with delivery, there were few opportunities for ‘browsing’. Beverly Kingston explained:

Samples might be proffered from time to time as an inducement to try a new brand, style or product, but except for the occasional suggestion from the order man, there was little likelihood of impulse buying, of making comparisons, or encouragement to vary shopping habits.

The convenience of a corner store, and deliveries to the back door, added to the cost of food. During the First World War an Interstate Commission suggested that delivery services should be rationalised because they added substantially to the cost of food. Commissioner, Mr Justice A.B. Piddington, noted that the grocery trade was rather over-supplied: at the time there was a grocer or general store for every eighty families in Melbourne.

A variety of horse-drawn commercial vehicles were used for delivering goods. Four-wheeled vans were mostly used by greengrocers, while meat, bread and milk was delivered in two-wheeled carts. Sometimes the carts were individually tailored for the job. Some butchers’ carts, for instance, had a ‘drop-down tailgate with a chopping block, and their scales hung from a special hook.’

The rise of the supermarket and car ownership saw the decline of the local grocer and home delivery, which had all but gone by the 1980s. Recent events have led to a resurgence of home delivery, albeit with a modern overlay. COVID restrictions have encouraged online shopping, seen by many as safe and convenient.

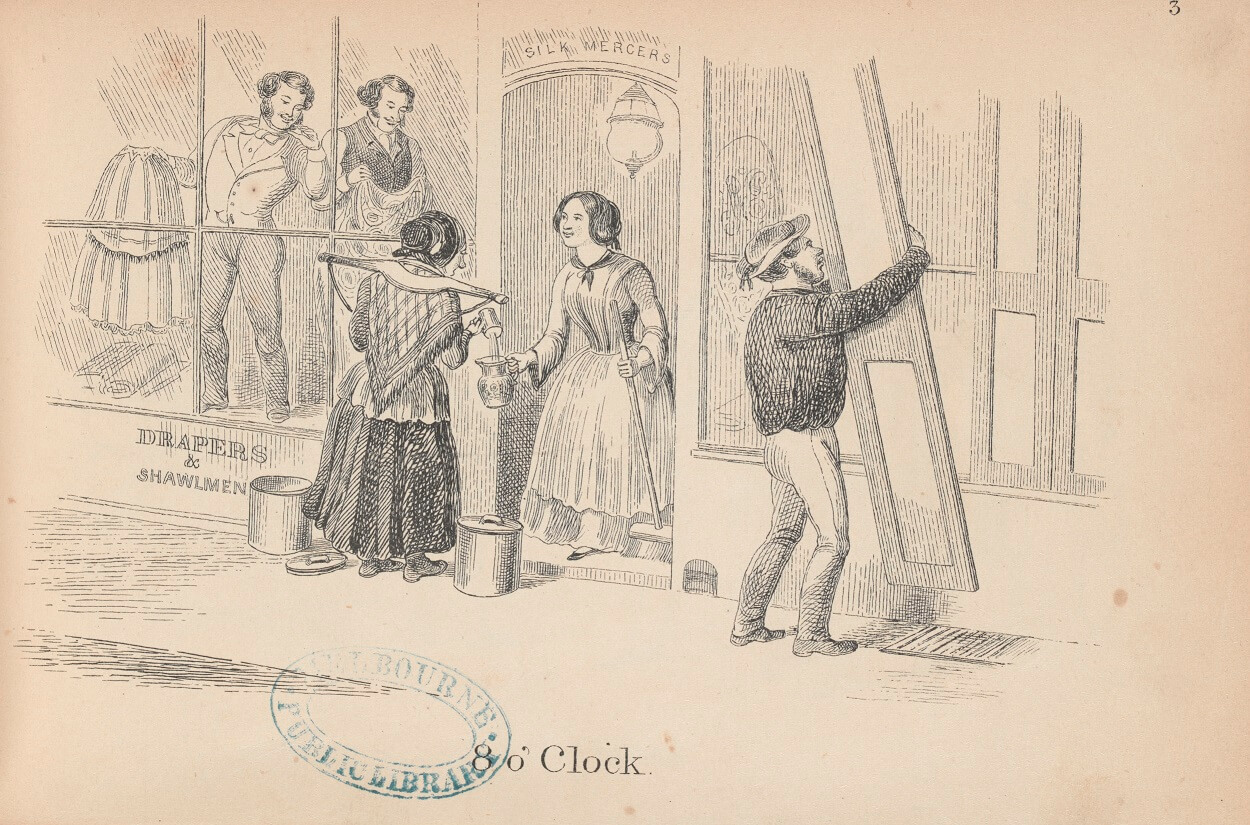

Dairywoman delivering milk, in ‘8 o’Clock’, by Henry Heath Glover, lithographer, 1857

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

Before refrigeration, milk needed to be produced and delivered locally. Many small homesteaders in early Melbourne had a house cow to provide fresh milk, cream and butter. Milk was delivered in an open jug or pail to those without a cow.

Until the 1920s dairy cows were kept in Fawkner Park, Royal Park and Princes Park, with fees paid to the Melbourne City Council.

Horse-drawn dairy van belonging to Craigie-Lea Dairy, Melbourne, c.1960

Courtesy Darebin Heritage

A common sight in inner-city Melbourne during the early to mid-twentieth century. Craigie-lea Dairy began operating in Thornbury in 1924 and still delivered milk by horse and cart in the 1970s.

By the late 1920s cows had moved from inner Melbourne to dairy farms outside the city. Suburban dairies, or ‘milk depots’, delivered milk to households by horse and cart. By 1920, there were some 400 dairies in the metropolitan area, and over 800 delivery carts.

Milk delivery continued in some areas until the 1970s and older Melburnians will remember waking to the clip-clop of the horse and the clink of milk bottles.

Initially milk was delivered in churns, with delivery men ladling milk for each house into a billy can like this one shown. Customers would either leave an empty billy at the gate or listen out for the horse and meet the milkman. The milkman’s horse knew the route as well as his master, standing patiently while the milk was delivered.

By the 1940s concerns for hygiene led to milk pasteurisation and delivery in sealed glass bottles.

Despite the introduction of the car, horse-drawn commercial vehicles continued in use for many years. According to historian, Margaret Simpson, the difficult economic circumstances and shortages of fuel during the World Wars and the Great Depression kept horse-drawn vehicles on the road when motor vehicles might otherwise have replaced them. The bakery run, requiring frequent stops over short distances, suited a well-trained horse. As with milk delivery, bakery carts lasted well into the twentieth century.

Stockdale's Bakery bread delivery cart, South Yarra, c.1945. Woman delivering bread, perhaps as a wartime measure.

Reproduced courtesy Stonnington History Centre

Commercial vehicles served to promote their company and carts were often highly decorated, with the firm’s name clearly visible on the side. Horse-drawn vehicle painters were fine craftsman. To a limited extent this tradition continues with trucks being personalised with signwriting.

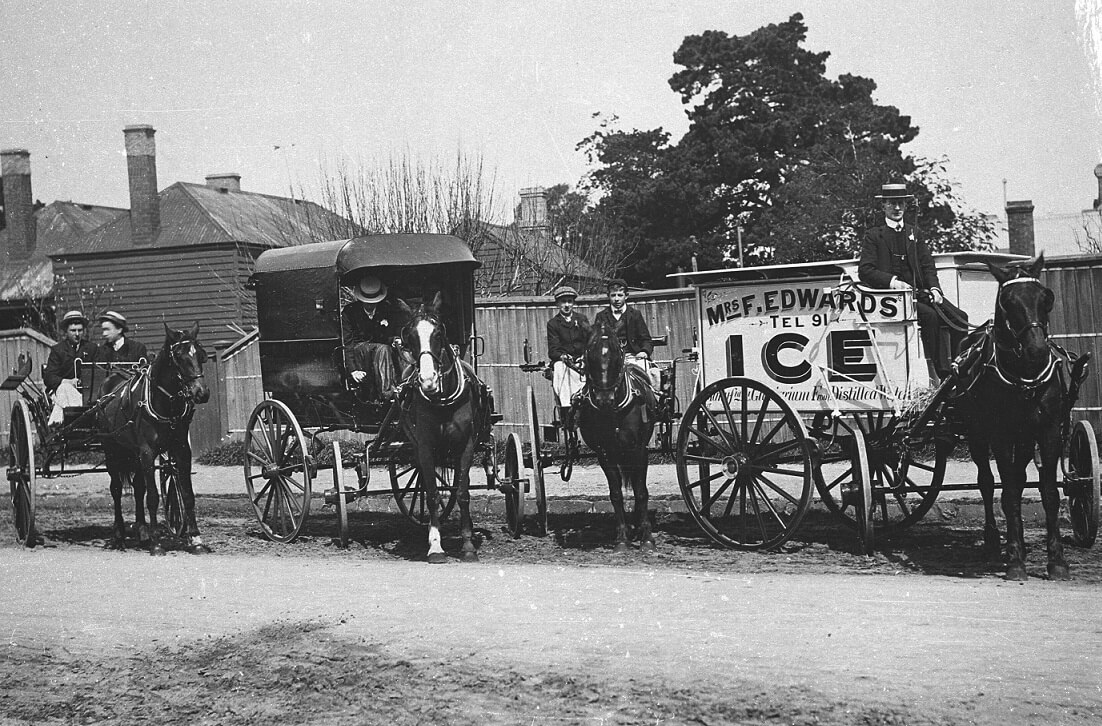

Ice carts owned by Mrs Fanny Edwards, 1908

Reproduced courtesy Museum Victoria

Mrs Edwards was a successful businesswoman, operating a store in Church Street, Brighton, after her husband died. The store delivered all manner of fresh food – milk, butter, eggs and ‘fresh rabbits daily’. Ice was ‘always on hand’.

Refrigerators were rare in Melbourne homes until the 1950s and households relied on regular deliveries of ice. The ‘iceman’ was a fixture on the roads during summer months, delivering ice once or twice each week, sometimes daily. The iceman would carry the block of ice into the house on his shoulder and put it in an insulated ‘icebox’, made of wood and lined with galvanised-iron or more expensive seamless porcelain enamel.

The invention of the domestic refrigerator was welcome and by 1955 67 per cent of Melburnians owned one. The iceman was out of a job!

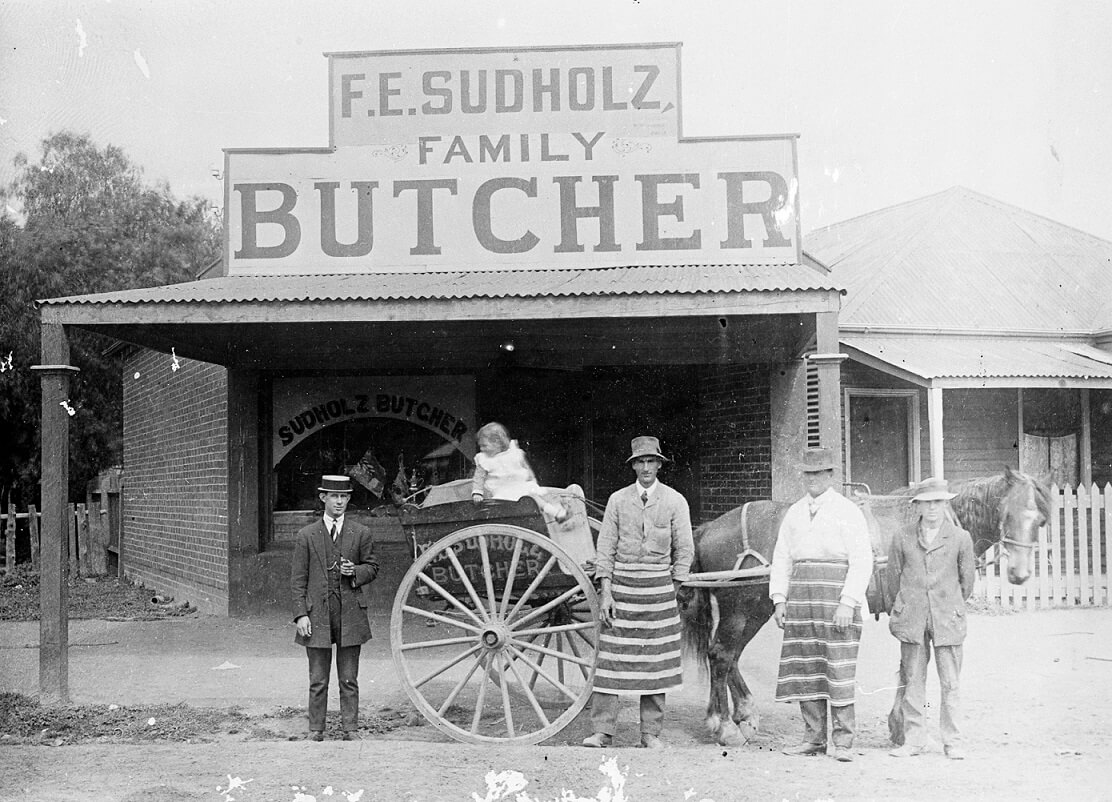

The butcher’s boy with his horse and cart delivered meat, sometimes daily. During summer this could be problematic. Meat was quick to deteriorate in hot weather and sometimes the outside of the meat turned black, although some butchers believed this meat was the tastiest!

Butchers received the most expensive orders on a Friday or Saturday, as this was the payday for most employees. According to historian, Geoffrey Blainey:

… an expensive joint of beef was usually ordered for the weekend roast. By Monday, however, money was less plentiful and so steak or sausages were likely to be ordered. By Wednesday, when the money was running very low, boiled mutton was favoured by many families. By Thursday, tripe, lamb’s fry (liver) or other offal would be the favourite meats.