Around about the 30's, I think, quite often you'd see an Indian hawker come around the farms. In those days very few automobiles of any sort and we farmer's [sic] wives were dependent on the horse and gig to go the several miles into shops - which wasn't very often - for our supplies. And we were very pleased to see these hawkers, they carried such a variety of tiny things that the housewife really depended on, tiny things that were so unimportant for other people, like needles and cotton and darning wool and little bits of material to make children's clothes, soaps, toilet soap. Some of us made our own soap but you couldn't wash your face with that, but he had beautiful soaps. And sometimes he carried cough medicines, and then of course he had curtaining and lengths for making dresses. And he was very welcome indeed.

One hawker that came to visit our place was Mohamed, he said his name was, and he was a very tall, over 6', and very well proportioned, and large beard, rather fine looking man, reminded me of Kipling's men of the hills that he spoke about. The men of the hills in Kipling's book, Kim, they were all very tall, large men, the men of the plains I expect were short, but he was a very tall, a very distinguished type of gentleman.

The van was just an ordinary covered wagon with the sides, I think they were mostly canvas with perhaps outside wood, and he'd let them down just to show us his wares that were inside, all nicely packed, and it was all very comfortable. It was pulled by one horse and there was no sleeping accommodation, I think he pitched his tent somewhere at night.

I think he probably pulled into a sale somewhere, or the markets, or somewhere near Bendigo and loaded up and then went through the country towns, and went right out to the farms and went back to replenish his store again.

Of course, everybody was clamouring around, the children were excited to see what was there - it was quite a red-letter day when the hawker arrived. And strangely enough these men were well-liked with the farmers, they got on well together. And children liked them too. Well, we'd get a few things that we needed, and sometimes they would always get some chaff from the farmer to feed the horse at night. Their upkeep, their overhead was nil just about, and I expect they made a good living out of it, and they camped the night there. And this Mohamed that called at our place was a good draughts player and would always come up with his draughts board underneath his arm to have a game with my husband. And my husband said he was a very good player. I expect he went through several of the farms in one day, two before lunch and two after lunch, but as a rule he called to us just before tea time, and after we bought what we wanted he would go away and have his own tea and then come down for his evening game of draughts.

I couldn't help but feel in his presence that he was a rather distinguished person. He was somebody you couldn't look down on in any shape or form, he had a dignity. I don't know what part of India he came from, you didn't discuss that sort of thing with him - vastly different to the two little Indians that we had working for us that were picking up the Mallee stumps, they would talk with us about the Punjab that they came from, and a little bit about their family, but this man you didn't take any liberties with him. He was a very fine gentleman.

He came about twice a year because he covered a lot of land. They were everywhere of course, I'm just speaking of Victoria, but I think they must have been in New South Wales too, and they covered a lot of land all around the countryside.

I must tell you about laudanum. Our little store sold a lot of laudanum when I went up there in the early days and I was told that the hawkers used to buy it all. It was a great pain killer, of course, it was used in the early days too. But I think also they could use it to put them to sleep - give them a few nice dreams, perhaps, something like opium, I don't know. So I said to the girls, I said, And do they take it all? And they said, They take all the laudanum. But I suppose they lived very monotonous lives and perhaps they liked to go to sleep, I think that's what they used it for. Very interesting people.

Sidney Myer started as a hawker - and so did Billy Hughes, the Prime Minister of Australia. Sidney Myer started in Bendigo, and look where he ended up, so it could have been profitable in those days, couldn't it?

I think everybody spoke highly of the hawkers that came our way. But the day of the hawker was just about over as soon as the motor car came and people bought their own cars and whizzed away to the shops - it was no distance with the motor car.

Then we had a different type of hawker came around in big flash cars, carrying carpets and expensive things, all ready to make some money out of the farmers who were getting on their feet. They weren't like the Indian hawkers though, not as genteel and they weren't as good company.

The Afghans with the camels have gone, all made Australia a very colourful place. Opened up the country, didn't it? But what us housewives would have done without the hawker I do not know. But they also did something more - they brightened our lives.

Recollections of Mary Staley, who had a farm at Natya, just north of Swan Hill, in the 1930s. Printed with permission from her daughter Eileen Watson, and son, Robert Staley

From the 1880s, hundreds of Indian migrants arrived in Victoria. Many worked as travelling ‘district hawkers’, selling groceries and haberdashery to households in the bush. It is hard to imagine the isolation of country Victorians in the nineteenth century. Farms were remote with only a horse and cart for transport and no shops within reach. For the farmer’s wife the Indian hawker was a welcome sight.

Indian hawker, Pollah Singh, with his customers in the Upper Murray area, Victoria, c.1905

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

Life as a district hawker could be lonely and physically demanding. Many of the hawkers travelled on foot, like Rooh-Rah-Singh, who worked the Goulburn Valley and North-Eastern districts for 30 years. He balanced his wares on his head, his dilly-bag of cooking gear slung across his back. More successful hawkers used a horse and cart. Meagr Deen near Echuca, for instance, had a ‘five-horse team hauling a large van’. When he reached a farmhouse he would open up the van, letting down one side to display the goods on the packed shelves:

There were elastic sided boots, braces and belts, socks and ties, fishing lines and cartridges and even mouth-organs or a concertina. For the ladies there were towels, aprons, stockings, children’s ware, dresses and an astonishing range of haberdashery. From one tin came imitation jewellery and from another came lollies for the kids.

District hawkers were an ‘interface’ between the shop keepers in town and farmers on the land —a ‘general store on wheels.’ Experienced hawkers catered for their customers. According to reports, Meagr Deen knew the ‘needs of the scattered housewives and could read their desires in a flash’. While on the road, the hawkers would stay overnight in farmers’ barns or sheds, or in farm accommodation erected for itinerant traders. Hawkers with wagons could simply pull up on public land.

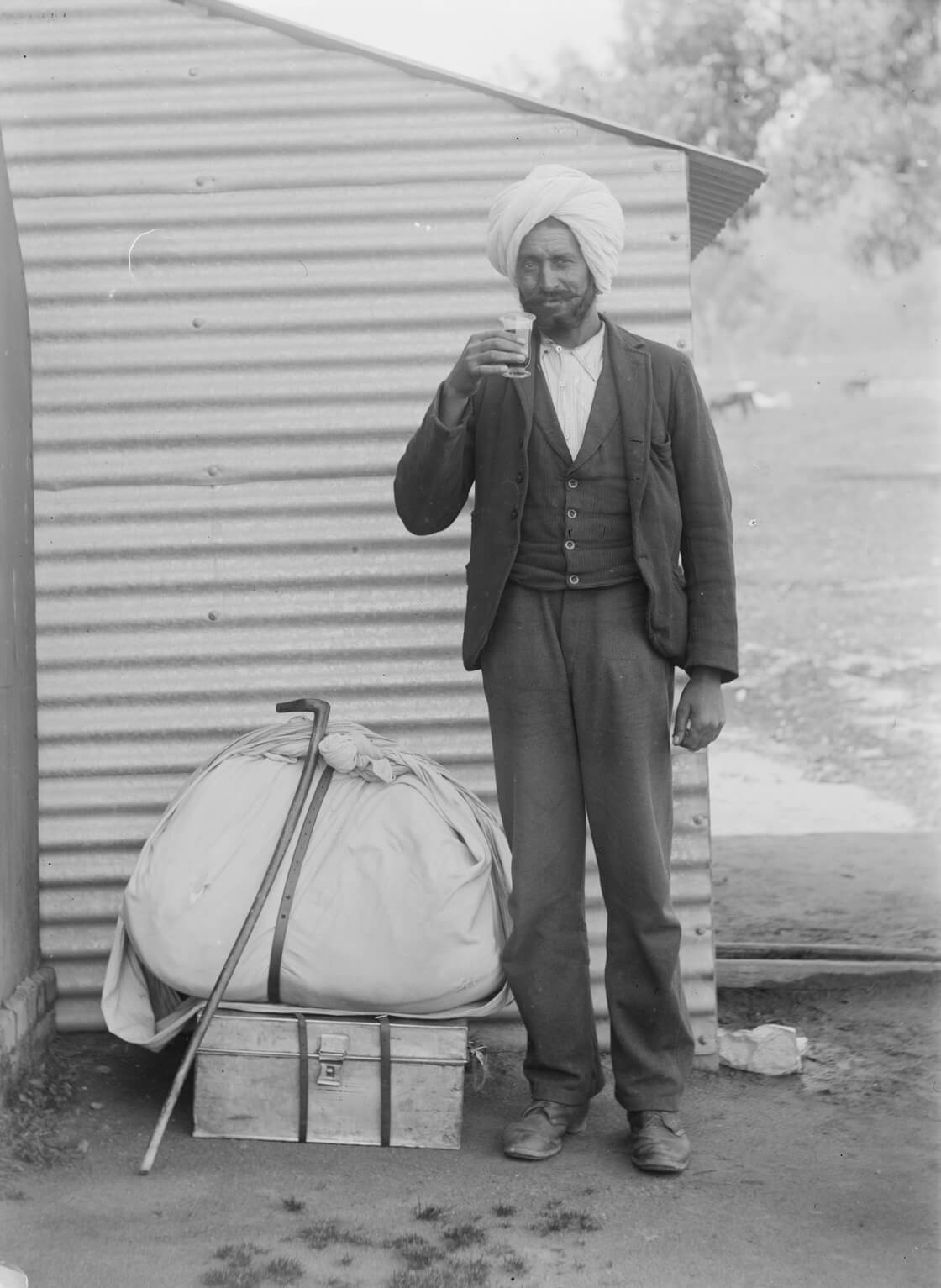

‘Indian hawker taking refreshment outside a house’, possibly in the Upper Murray area, by Gabriel Knight, photographer, c.1905

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

Some of the hawkers decorated their vans, which delighted children on the farms. A young Barry Watts remembers Yokum’s visits to his grandmother’s house in Yarra Glen in the early 1940s:

He drove a high covered wagon with two horses, but they were unlike any other wagon and horses seen in the district. Yokum’s wagon had exotic, colourful scenes of distant landscapes painted on its sides. To a child it looked fantastic...and I danced around it with a feeling of excitement and discovery. The tray part of the wagon was highly decorated with scrolls and flourishes as well. The horses were driven one in front of the other, and their collars and harness had small bells and reflective sequins attached so that every step, every movement, every shake of a horse’s head, produced a soft tinkle or sparkling glitter.

Indian hawkers undoubtedly experienced discrimination as they traversed rural Australia and merited occasional mention in the press – the men represented as a threat to women alone on farms and accused of taking the jobs of ‘deserving white men’. These incidents were rare, however, and most hawkers are remembered affectionately as an important part of the bush economy, plying their trade until the 1950s when the car transformed rural life.

For more on the prejudice the hawkers’ experienced, see Museums Victoria.