Swagmen, or ‘swaggies’, were itinerant workers. They led a nomadic life, tramping along country roads from farm to farm, looking for seasonal or casual work — a situation described as being ‘on the wallaby’. Swaggies got their name from the ‘swag’, or bundle of blankets and possessions, they carried on their back. Their numbers increased in times of economic uncertainty, such as the depressions of the 1890s and 1930s.

Most swaggies were men, but there were a few women on the roads. There were reports of a swagwoman in Ballarat in 1902, carrying her swag, a billy and a bag of tucker. She attracted considerable attention:

Two children were hanging on to the skirts of the female sundowner, who had travelled from one of the farming centres in the Wimmera district. She was a big, bony woman, and boasted she could break stones with the best man in the States.

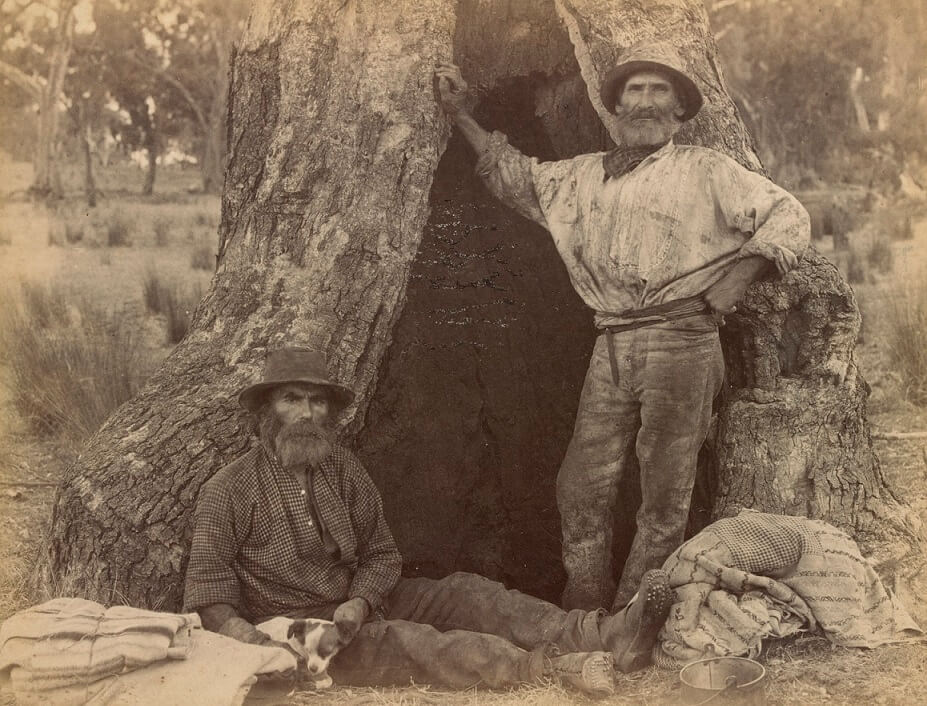

For the most part, swagmen travelled alone. They camped under a tree, their swag unrolled on the hard ground. They had very few possessions, limited by what they could carry — their swag, a tucker bag (bag for carrying food) and some cooking implements such as a ‘billy’ (tea pot or stewing pot). Sometimes they carried flour for making damper and some meat for a stew.

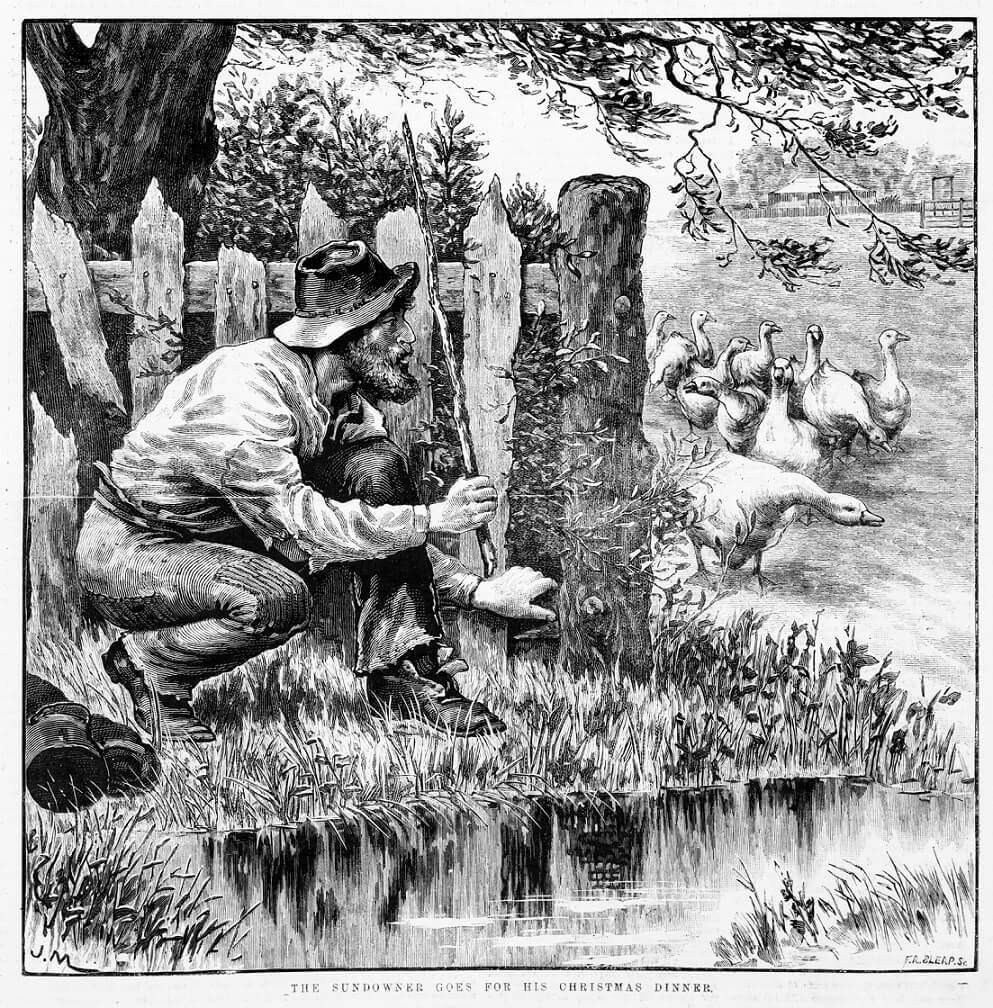

‘The Sundowner Goes for His Christmas Dinner’, by F.A. Sleap, artist, printed by David Syme and Co., 1885

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

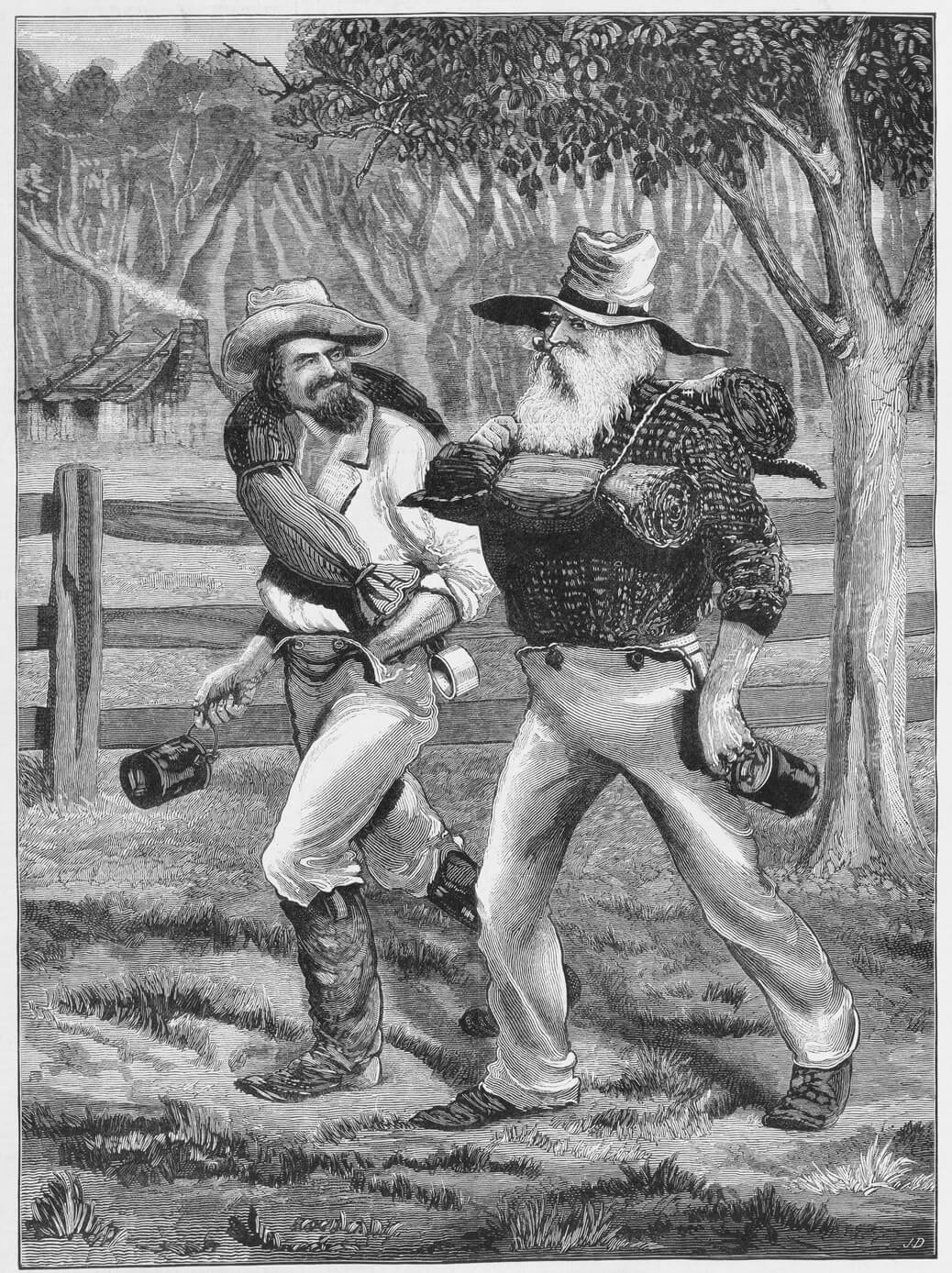

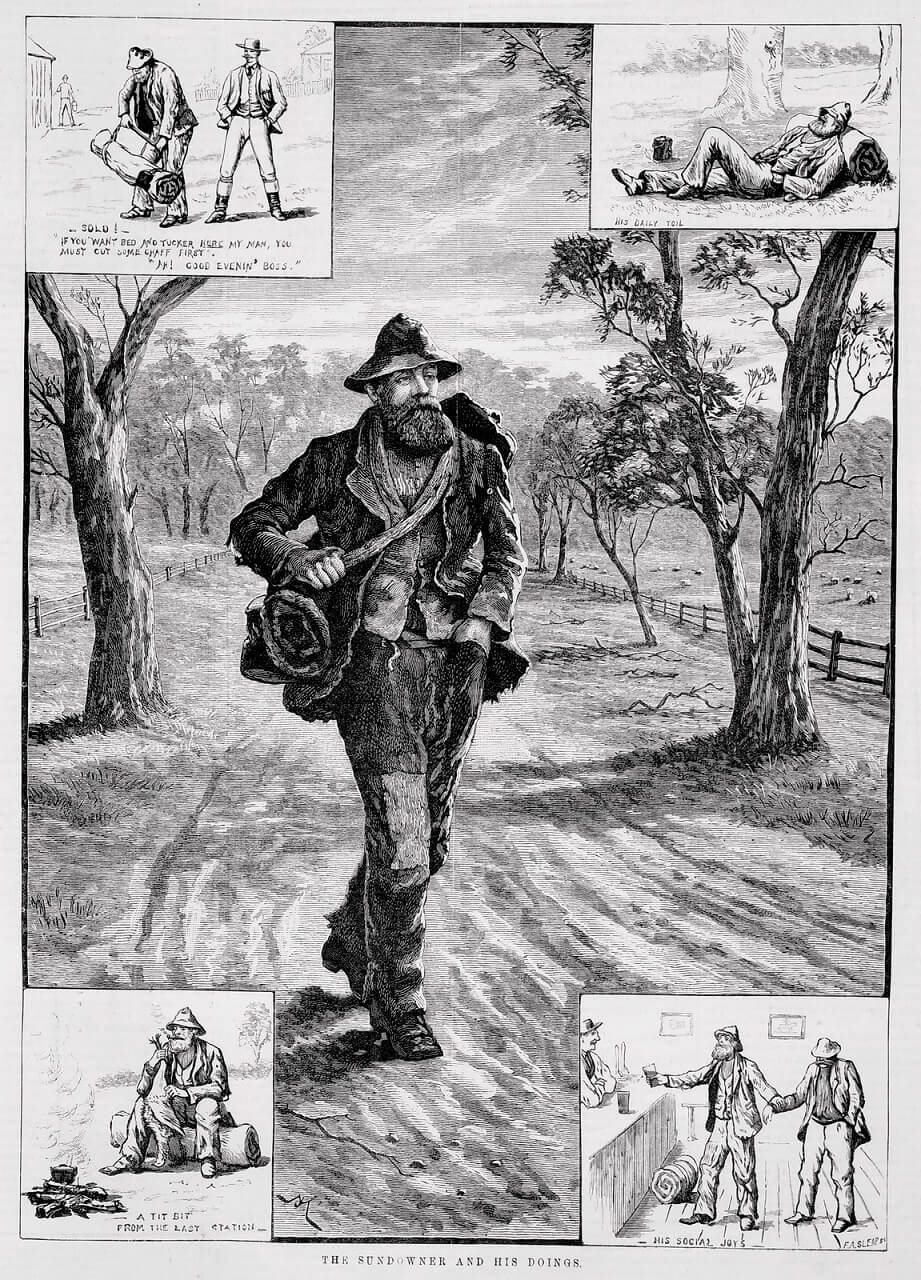

Not all swagmen were hard workers. Some swaggies would arrive at homesteads or stations at sundown when it was too late to work; receiving a meal but disappearing before work started the next morning. They were described as ‘sundowners’.

‘Sundowners’, printed by Alfred May and Alfred Martin Ebsworth, 1881

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

Folklore has romanticised the swagman, making him (or her) personify adventure and a free-living Australian spirit. But the life was hard, battling poverty and loneliness. There were long spells of unemployment and constant travel. In fact, as historian Bruce Scates notes, many swagmen ‘perished in the wilderness, with their boots worn and their swags empty’. By the 1950s, with a growing economy and welfare, swagmen were a rare sight.

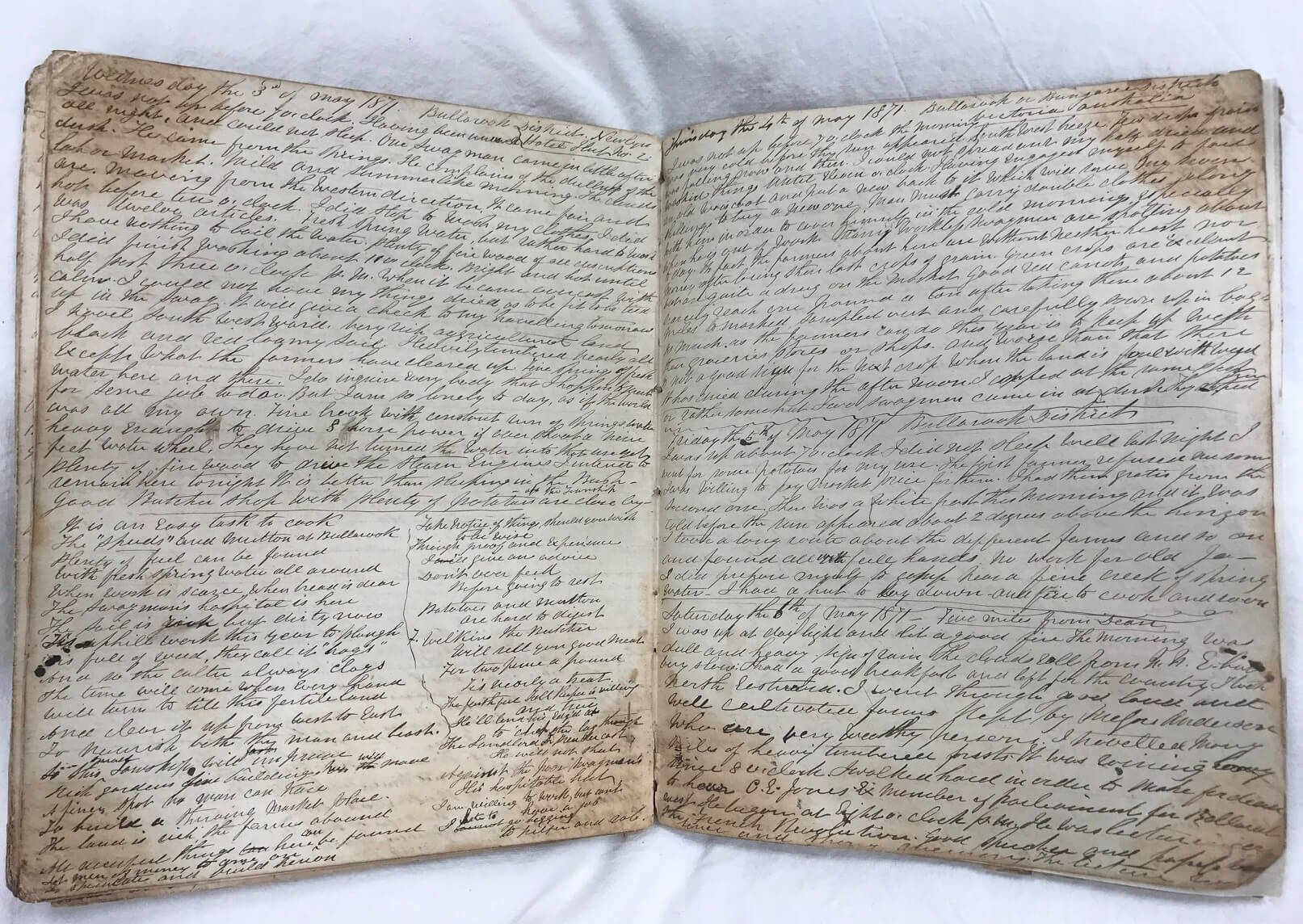

Diary of Joseph Jenkins, the ‘Welsh Swagman’, entry for Wednesday 3 May 1871: ‘I am so lonely to day, as if the world was all my own’.

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

On display in the exhibition is the diary of Joseph Jenkins, on loan from State Library Victoria. Jenkins was born in Wales in 1818. After his marriage to Elizabeth Evans, daughter of a wealthy farm owner, Jenkins acquired the tenancy of a farm near Tregaron. He became a successful farmer and an influential figure, involved in local politics.

In 1868, at the age of 51, Joseph Jenkins abruptly abandoned his wife and eight children and sailed to Australia. His reasons for leaving are not known although historian, Bill Jones, suggests he may have left home to escape deteriorating personal problems, ‘notably worsening relations with his wife as a result of his excessive drinking and neglect of the farm’.

Jenkins arrived in Melbourne in March 1869. For the next 25 years he travelled the colony as an itinerant agricultural labourer, or ‘swagman’, mainly in the Ballarat, Castlemaine and Inglewood areas. During this time, he kept a daily diary.

His diary is a wonderful source of information about the life of a ‘swagman’. Jenkins commented on the availability of work and the cost of food. He describes finding seasonal work splitting timber, felling trees, carting hay, ploughing fields, planting and picking potatoes and digging unsuccessfully for gold - ‘Gold never glitters in my hand and never will’.

He wrote about farm owners and farming methods, of which he was generally unimpressed:

Thousands of acres of fertile land around Smeaton, but poorly farmed. The farmers consider it too expensive to cart farmyard manure to the land, so they pay 9 shillings per hundredweight for potatoes which they are unable to grow. No land is properly cultivated around here except the townspeople’s gardens.

Unusually, he showed both interest in and empathy with First Nations people. In July 1874, while a patient in Maryborough Hospital, he was upset by the treatment of a man after his death: ‘No more heed or notice taken of his death than if he was a common fly or moth’. In 1887 he met a First Nations man named Equinhup and wrote:

He seemed half starved. I took him into my cottage and invited him to share a meal with me. I shared my blankets with him during the night. A few men in the colony own over a million acres of rich land which was barbarously taken from the Aborigines. The majority held it as of right and even a Christian obligation to be rid of all the Aborigines. In the name of everything – whence came such authority?

It was certainly not an easy life. Jenkins had to ‘labour under a heavy swag’, mostly sleeping in the bush, or if he was lucky, in a haystack. He would often walk all day but find no work. He commented often on his health, and the state of his teeth: ‘toothache has plagued me off and on for weeks; it disturbs my sleep’. At one point he listed his current ailments — ‘toothache, rheumatism, sore eyes…whitlow on my finger, and abscess in my armpit.’

Eventually life as a swaggie took its toll and in 1894 Jenkins returned to Wales, to the family and personal conflicts he had left. It was not a happy homecoming and he took to drinking, dying four years later.

For more information on Joseph Jenkins, see Bill Jones, ‘Jenkins, Joseph (1818-1898), Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/jenkins-joseph-13007

For more information on Jenkins’ diary, see Rachel Solomon, The Victorian Diaries of a Welsh Swagman (1868-1894), La Trobe Journal, No. 92, December 2013

‘Once a not so jolly swagman: the story of Joseph Jenkins’, by Gary Hill, accessed online https://www.irefuteitthus.com/story-of-joseph-jenkins.html

A Sundowner’s Camp, by N.J. Caire, photographer, c.1886

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

‘The Sundowner and His Doings’, by F.A. Sleap, artist, printed by David Syme and Co., 1885

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria