According to historian, Andrew May, there were four main types of hawkers in early Melbourne: fish hawkers, flower sellers, fruit and vegetable traders and hawkers of miscellaneous goods, including ‘trinkets, toys, oysters, drapery, Turkish delight, stationery, cigars, patent medicines, and razor paste’. In the early 1850s, less than 100 hawkers were licensed in Melbourne, but this number had swelled to almost 1,000 by the turn of the century.

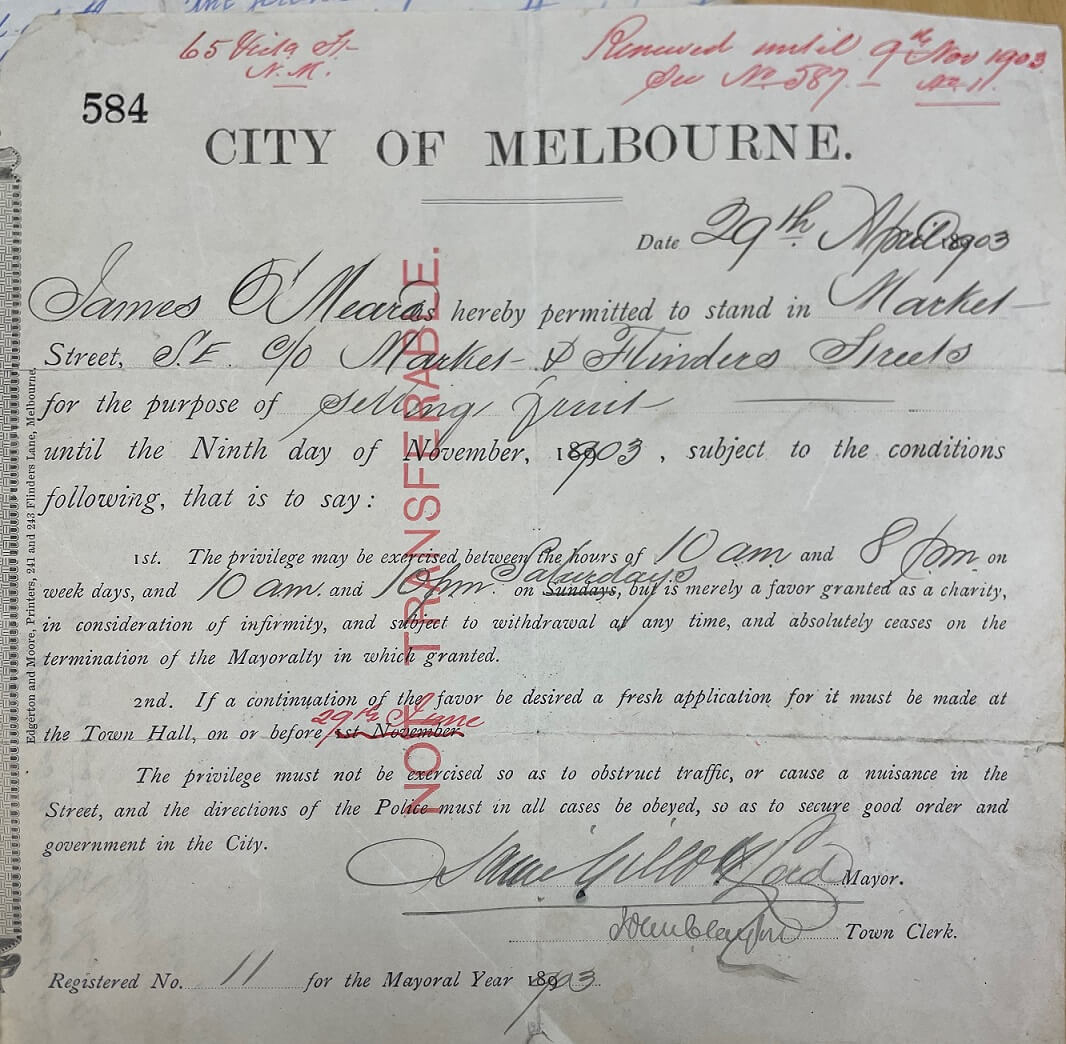

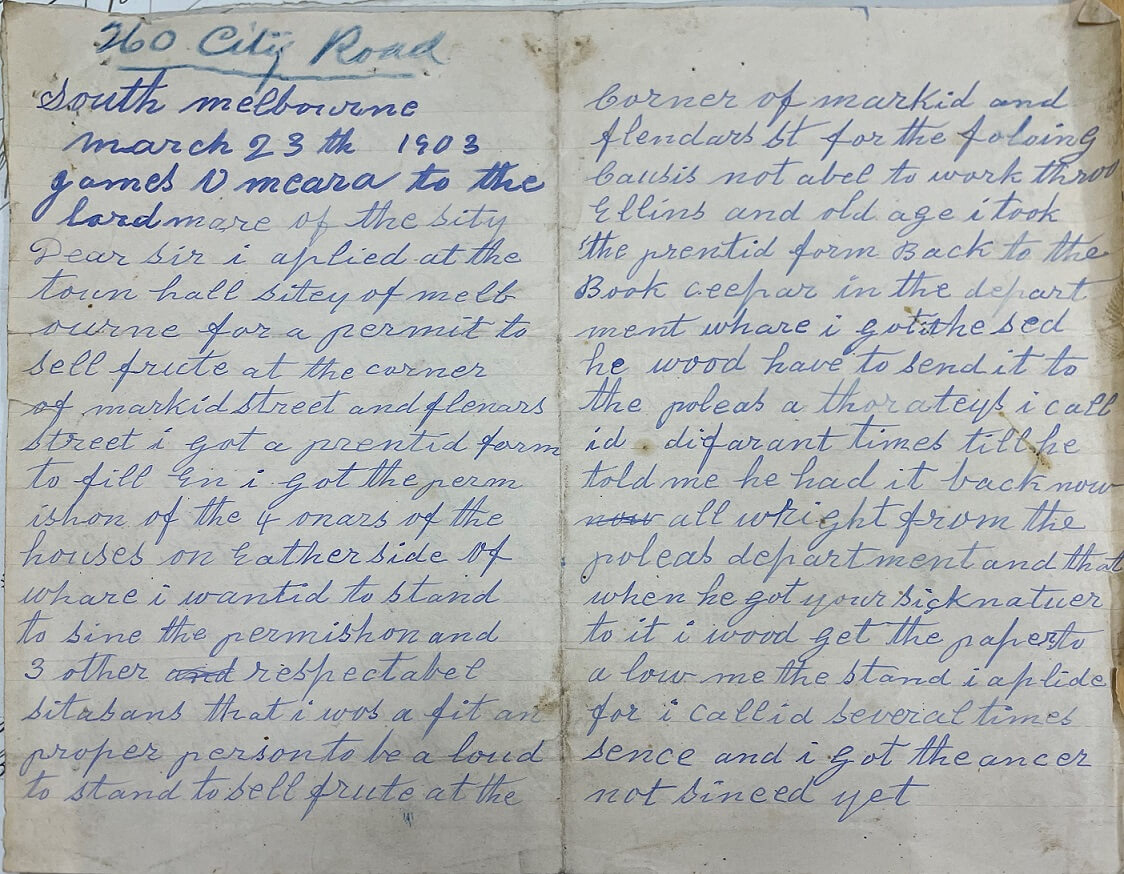

From the 1860s the Melbourne City Council regulated (and licensed) street traders. They specified location, what was sold and the hours of trading. They even demanded signatures from nearby shopkeepers, consenting to the ‘pitch’. Applicants had to prove that they were elderly, disabled or unable to perform manual labour. James O’Meara was one such applicant. He applied for a fixed-stand to sell fruit in 1903. In his application James stated that he did not see ‘Aney resorce of earning me one living’ as he was ‘subgect to rumatisam’. He was granted permission to sell fruit on the corner of Market and Flinders streets.

It may be an indication of the passing of the “good old days” to find that the ice cream of our childhood is to be replaced by a scientifically-made concoction that will reduce to a vanishing point the possibility of indulgence in the delicacy being followed by any of those untoward developments which were once accepted as one of the risks of the investment.

But still people were poisoned. Several people became seriously ill, and one died, in Collingwood in 1918. The seller had used a can of condensed milk which had been opened 12 days earlier.

Street ‘demonstrations’ were popular in early Melbourne, particularly at night. On offer were lung testers, weighing chairs and lifting machines. For only 3d, an ‘electrician’ would shock you, making you ‘stand on the tips of your toes’. A street astronomer, or ‘telescope man’, showed Saturn’s rings and described Jupiter’s moons for a glass of gin.

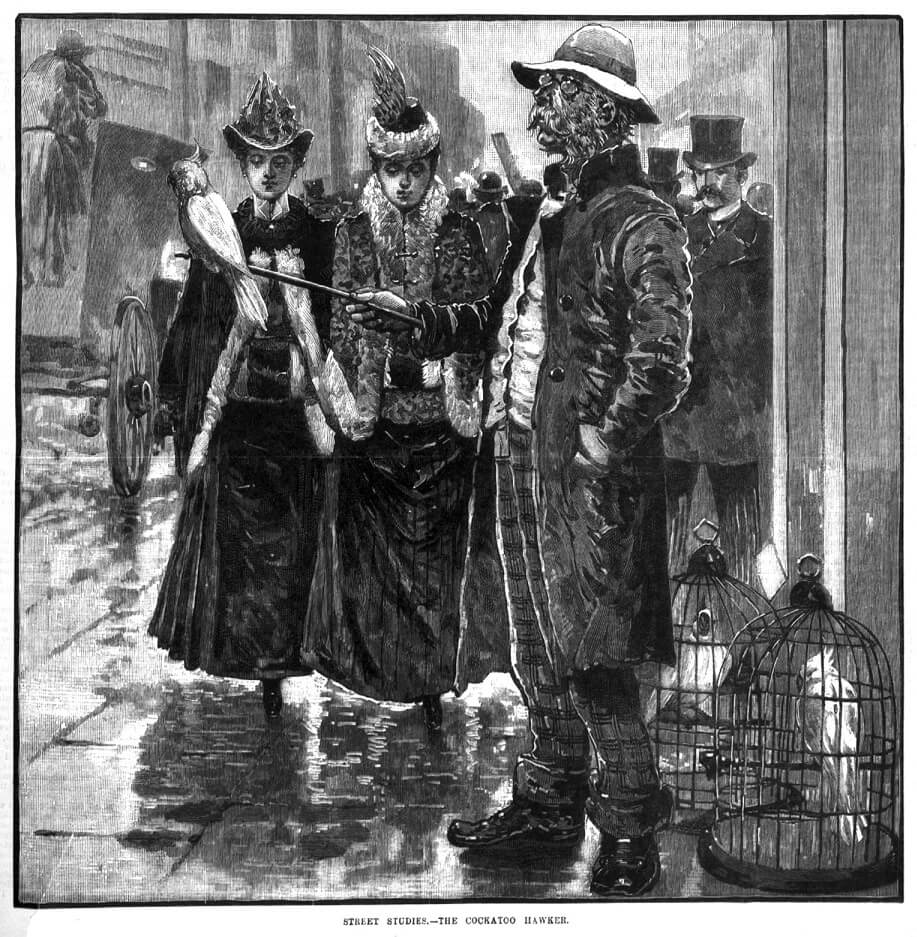

The ‘Cockatoo Hawker’ was another unusual sight on the streets. He was described in the Australasian Sketcher in 1887:

The ' Cockatoo Hawker' belongs to the soil. He is to be found at odd times near the corner of Elizabeth-street and Flinders-street. For weeks you may pass this spot and there will be no sign of him, but a thoroughly fine day may bring him out. He is at his post today, so let us note him. In one hand he holds two caged birds, while with the other he thrusts out a stick on which a melancholy cockatoo sits and surveys the passers-by. Our hawker wears spectacles and shaves under the chin, and wears his clothes with an air. Altogether he gives one the impression of a man who has seen better days, and who has taken to cockatoo selling because it is easy, and perhaps because it affords him opportunity of critically surveying the busy world he no longer mixes in.”

James O Meara’s application for a fruit stall in Melbourne, 1903

Courtesy Public Record Office Victoria, VPRS 3181/P0, unit 902

TRANSCRIPTION:

James O meara to the lord mare of the sity

Dear Sir i applied at the toun hall sitey of Melbourne for a permit to sell frute… i got a prentid form to fill en i got the permishon of the 4 onars of the houses on eather side of whare i wanted to stand to sine the permishon and 3 other respectabel sitasans that i wos a fit and proper person to be a loud to stand to sell frute… for the foloing causis not abel to work throo ellins and old age… i am wateing to se if you will be kind A nuff to send me an ancer to this for all the money i have got will be run out this weak next weak i will have to a ploy for the old Age penshon i dont like to do so as long as i can see Aney resorce of earning me one living… I am to subgect to rumatisam to troy to halk frute throo the st.

James’ letter shows the semi-phonetic spelling that was common amongst older working people, many of whom had received very limited schooling.

Fruit and vegetable hawkers were the largest category of street sellers, and market gardens along Merri Creek and in Caulfield, Brighton, Doncaster and Dandenong supplied the produce. By the 1870s a large number of the fruit and vegetable hawkers, or ‘costermongers’, were Chinese, but later Greek and Italian immigrants dominated. There was some hostility towards ‘foreigners’ running street stalls. Racial prejudice fuelled this social anxiety with reports of Chinese hawkers targeted, taunted and attacked, their wares stolen, and their carts destroyed.

Chinese Costermonger, 1868

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

Fruit and vegetable hawkers on Princes Bridge, by unknown photographer, c.1910

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

This cartoon, published in Melbourne Punch in 1872, mocks the pidgin English used by the Chinese hawkers.

Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia

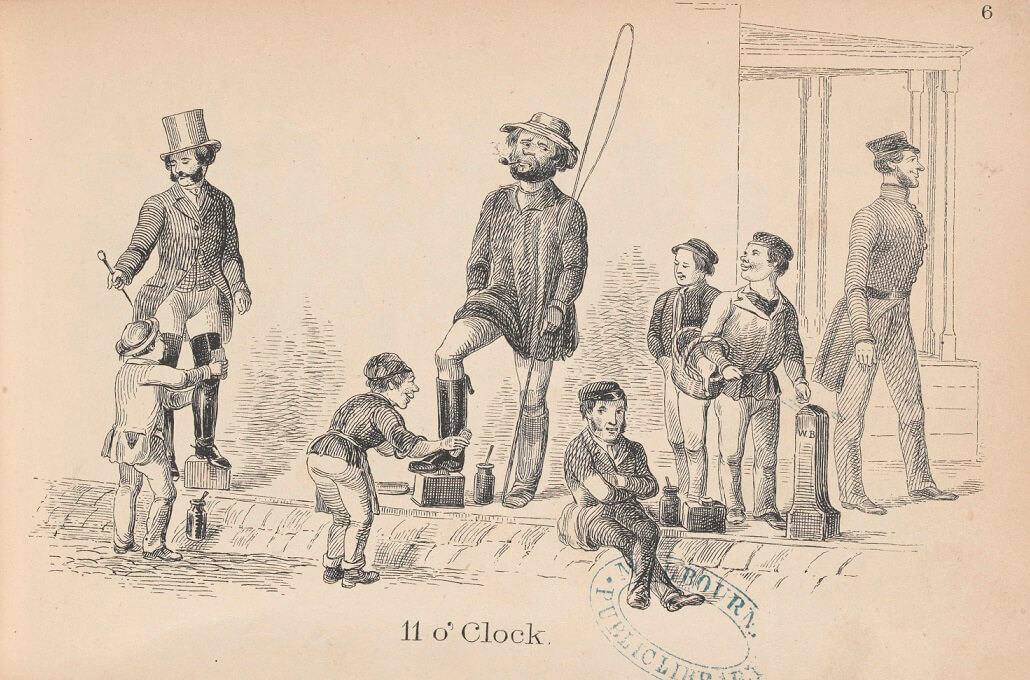

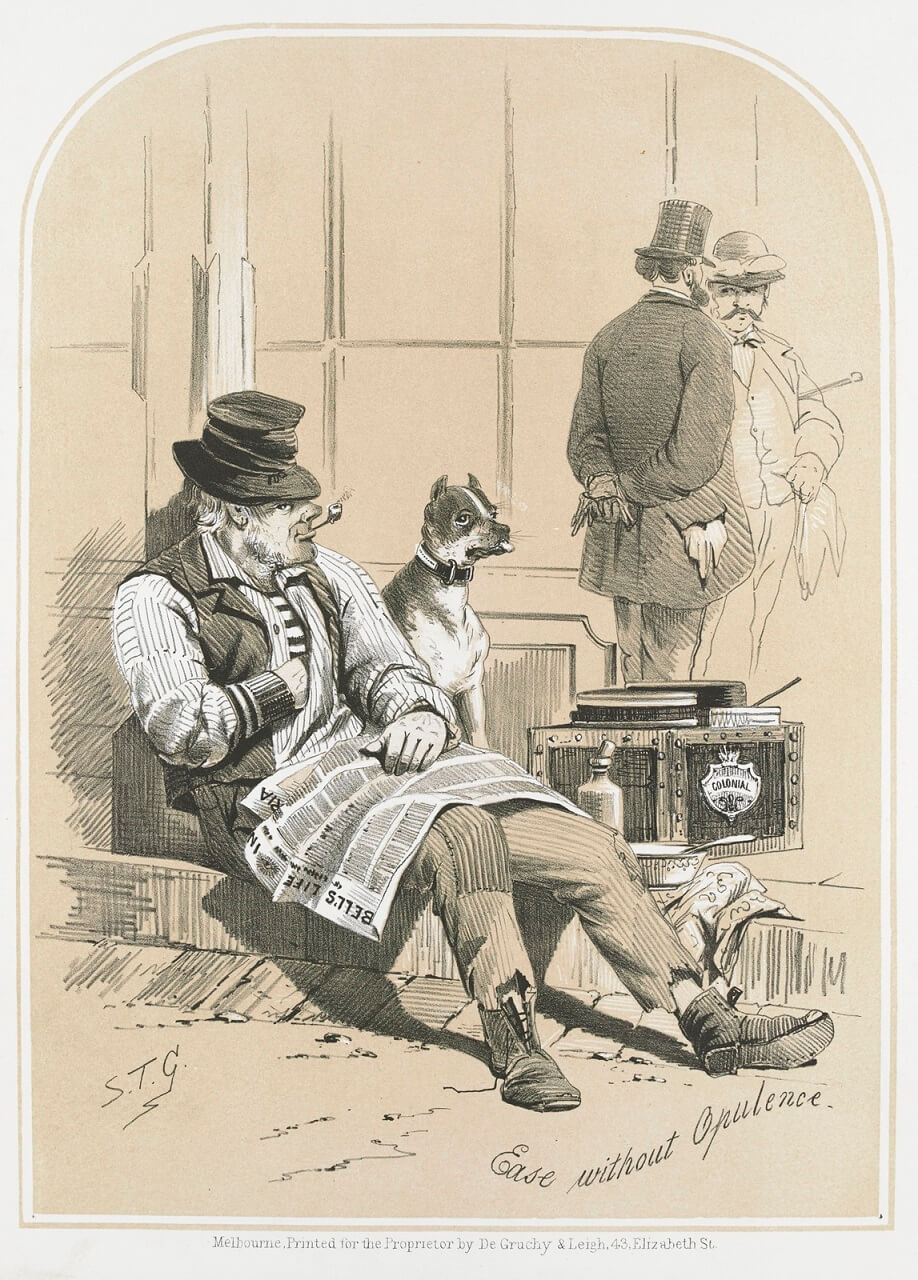

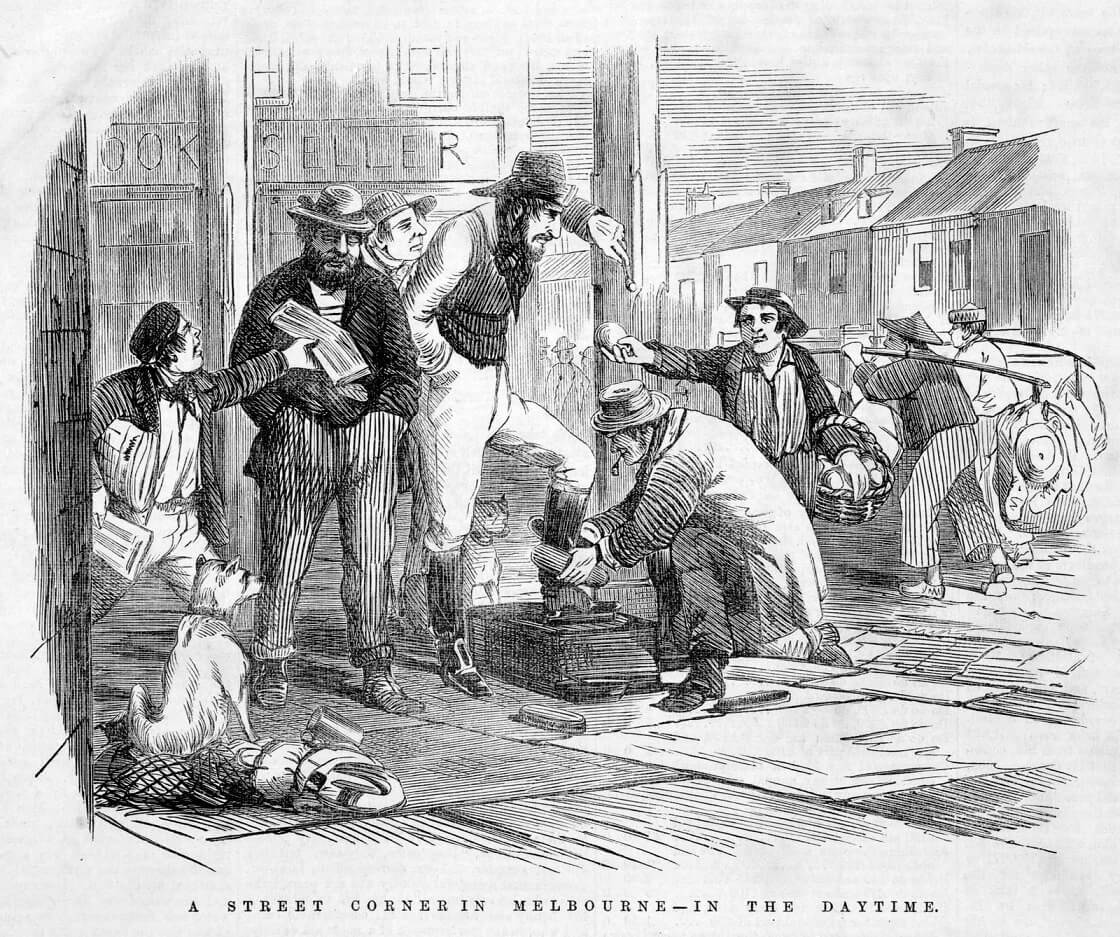

Bootblacks

Bootblacks were a common sight on the streets, appearing from the early 1850s. Originally a trade practised by children, by the late-nineteenth century, older men had taken their place. Many bootblacks remained at the job for a number of years, often at the same pitch. One bootblack, Michael D’Arcy, started shining shoes in 1864 and worked outside Stutt’s Hotel on the corner of Bourke and Russell streets for 35 years.

Bootblacks congregated in areas of the city such as Bourke Street, where theatres, restaurants and wine saloons ensured trade. By 1882 there were at least 14 bootblacks in Bourke Street alone. In contemporary images the bootblack was often characterised as a poor, dirty and dishevelled old man, perched at the gutter’s edge.

Children bootblacks, in ‘11 o'Clock’, by Henry Heath Glover, artist, 1857

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

A bootblack, in patched and torn trousers and broken boots, sits at the edge of a gutter, reading a newspaper, by De Gruchy & Leigh, lithographers, 1866

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

A bootblack works a street corner in Melbourne, 1863

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

Fish Hawkers

Hawking fish was the most profitable of street trades and hawkers sold their wares from barrows. They had a poor reputation. Traders cleaned their produce in the city's horse troughs and, at the end of the day, emptied their barrows full of fish scales and slimy water onto the street. Shopkeepers complained about the smell of the fish, the persistent flies and the hawkers’ bad language. According to Brown May:

The nuisance of fish hawkers in Flinders Street led Annie L. Burbury to complain in 1911 that the hawkers ‘camped’ outside her premises attracted flies which spoiled the pounds worth of Christmas cards on view at her stationary shop.

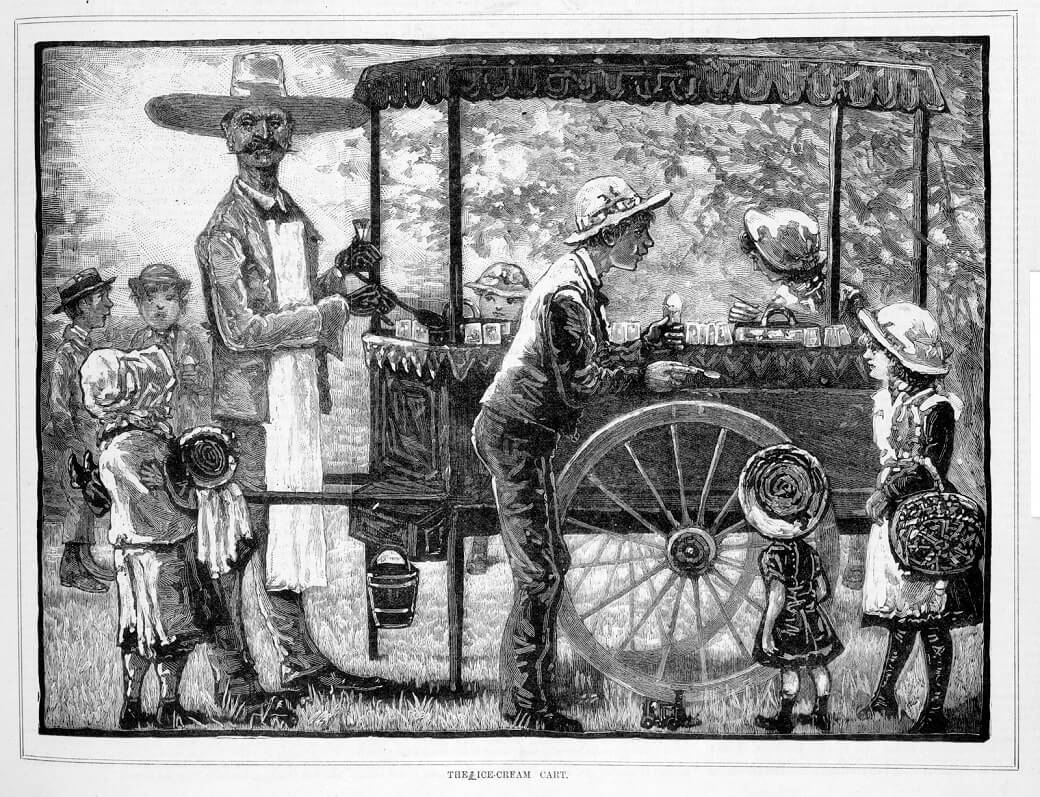

Seasonal Work

Some of the street trades were seasonal. Ice-cream carts, for instance, appeared only in the summer. Traders, like widow Jane Anderson, sold ice-cream in the warmer months and saveloys in winter. Ice-cream was sold in glass goblets, which were then washed and re-used. Unsurprisingly both the quality of the ice-cream and the level of hygiene was variable. One hawker was even caught cleaning his goblets ‘in water from the channel in Queen Street the gutter before serving a customer.’

The Pure Food Act 1905 addressed the issue of hygiene and attempted to regulate the sale of ice-cream. The Argus reported:

‘The ice-cream cart, Melbourne’, by Alfred May and Alfred Martin Ebsworth, lithographers, 1882

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

The Cockatoo Hawker, Melbourne, in the Australasian Sketcher, 1887

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

Most street sellers were men and by 1916 it was illegal for women to be involved in street selling. Women on the streets had few options; and most were widows with children to support. Mary Ann Hayes, a 47-year-old widow with seven children, operated a fruit stall in 1877. Another widow, Anna Farrant, had a newspaper stall in 1901. She had poor sight and two children to support and was too frail for factory work. Author Fergus Hume wrote about Farrant in his novel, The Mystery of a Hansom Cab, published in 1886:

against the verandah post, in the full blaze of the electric light, leans a weary, draggled-looking woman, one arm clasping a baby to her breast, and the other holding a pile of newspapers, while she drones out in a hoarse voice, “Erald, thord ‘dition, one penny!” until the ear wearies of the constant repetition.

Without state welfare, hawking was one of few options available to the old and disabled. Ada Broughton, a partially-blind single mother, survived in the early 1890s, selling flowers and singing in the streets. It was a precarious existence. She was eventually arrested and separated from her youngest child. The Age reported:

A pitiful case was investigated by the Carlton magistrates on Saturday, when Plain Clothes Constable Booth applied to have the infant child of a woman named Ada Broughton committed to the care of the department as being neglected.

The evidence showed that the mother had been considered absolutely destitute owing to the death of her husband. She was living in a two-roomed house, the windows of which were all broken, and the place was not fit for habitation. She had to support two children, one being an infant in arms. For some weeks the unfortunate woman has been earning a few pence by selling flowers and singing in the streets of the city, but Constable Booth informed the bench that the infant was dying from exposure to the night air. He thought the mother might be able to manage with the other child, as, if she were relieved of the infant, she would be able to get respectable employment, being a hard working woman.

Ada’s youngest son, Frederick, was separated from his mother and committed to the Neglected Children’s Department in 1898. He was only two years old.

Young Hawkers

The street was also a workplace for children. Children sold flowers, fruit, bottles and bric-à-brac from handcarts, and shone shoes at the gutter’s edge. Some enterprising children earned extra pennies catching rats for the council: tuppence per rat was the going rate in Port Melbourne in 1902. Others held the reins of riding horses for a small fee. As Andrew May notes:

In 1889, Police Sergeant Holland noted in a report on Melbourne’s General Cemetery that ‘a number of youths 14 to 16 years of age come there with funerals for the purpose of holding horses during an interment for which they may get a shilling or sixpence.’

Street work was dominated by boys. Some girls took part, usually selling flowers or newspapers, but they were, as historian Simon Sleight points out, ‘widely regarded with apprehension, and sometimes in sexualised terms’. Young female sellers were often cast as ‘fallen’. Illustrating this point, the Argus reported in 1881:

Some months ago Senior-constable M’Hugh arrested a man for following and making improper overtures to two evening newspaper girls, the eldest of whom was only 11 years old, but, he adds, it was found on inquiry that the girls had already fallen into immoral habits.

Earnings on the streets varied. According to The Argus flower boys in the 1890s pocketed from 5 to 15 shillings per week. Some newsboys earned 18 shillings per week, ‘but these are the Rothschilds… of the profession...’ Children were of course paid much less than adults. Even an unskilled male labourer earned 25s per week in the 1880s.

Young flower sellers on Princes Bridge, by unknown photographer, 1903

Reproduced courtesy Italian Historical Society & Museo Italiano

“Please Buy” (From a painting by H.J. Johnstone), by Samuel Calvert, engraver, printed in the Illustrated Australian News, 31 March 1888

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

Both art and literature have romanticised the innocent young girl, selling flowers to support the family, but in reality, her life was harsh. The Illustrated Adelaide Post reported in 1867:

The Melbourne flower girl, like her English sister, offers a marked contrast to the wares in which she deals. Haunting the streets by day, and the entrances to our theatres by night, living, If not in hunger, at any rate In "poverty and dirt", she does not seem to snatch a single grace from the beauty which surrounds her.