… the newsboy... is essentially a child of the street, a nursling of crowded city life, one of the half-reclaimed waste products of civilisation. In Melbourne his special arena is the space between Burke and Collins Streets, and it is there that he fights out the battle of existence.

Lyttelton Times, 7 January 1899

The newsboy was a ubiquitous urban figure. Newsboys (rarely newsgirls) first appeared on city streets in the mid-nineteenth century. For more than a century they stood at street corners, tram stops, or ‘Under the Clocks’ at Flinders Street Station, calling the headlines. The age of newsboys ranged from seven to 19 years. Many were wretchedly poor and homeless, surviving independently to avoid the schools for ‘neglected’ children. Some supported single mothers and their siblings. As with flower sellers, art and literature focussed on this version of the newsboy. The Herald published the following story of 14-year-old newsboy, ‘Jimmy’, in January 1896. Jimmy was the only support for his widowed, crippled mother:

He was the neatest and most civil of all the Melbourne “Herald” boys… He didn’t associate much with the other boys – never played “pitch and toss” with them, nor joined in a cry of “Hold ‘er tight”, whenever a lady cyclist happened to pass. It wasn’t because he was proud or stuck-up that he didn’t mingle with his comrades, and join in their pesty frolic, for Jimmy was as kind and gentle a boy as you’d meet anywhere. No! It was because there was something in his life which beclouded his young mind with the sadness of a man, and bred an earnestness of purpose almost painful to see in one so young.

Jimmy’s story ended (somewhat predictably) in tragedy. Hurrying home to his mother one afternoon, Jimmy was knocked down by a tram and killed.

Read the (fictionalised) story of ‘Jimmy’, a Melbourne newsboy here. Courtesy National Library of Australia

A spark of ‘romance’ was attached to the newsboys’ life – if his life was hard, it was at least full of excitement! The reality was probably very different. Newsboys endured poor working conditions, often working 15 hours per day. Newspapers were heavy – a stack of 50 papers weighed around 10 kgs – a substantial weight for a young boy to carry, and they did not eat regular (or healthy) meals. Newsboys risked injury as they darted between the busy city traffic and contemporary newspapers are filled with reports of newsboys killed or maimed on the job. A ‘cripple newsboy, well known in the city’ was knocked down by a tram in Collins Street and killed in 1889. Norman Holmes, aged 13, was run over by a motor car and killed in 1931. Henry Osborne, aged only 11, died when he was struck by a van at Richmond in 1933.

The image of the newsboy, paper in hand, dashing in and out of traffic, became iconic. He was portrayed as quick-witted, street-smart and lively - ‘seen to embody the best characteristics of innumerable street-based apprentices across the nineteenth and twentieth centuries’. But some rejected this attractive image, viewing the newsboys as a loud and obnoxious annoyance. The following letter was published in the North Melbourne Advertiser in August 1892:

The principal streets of Melbourne are crowded with hordes of boys yelling in ear-splitting tones the names of the evening journals, and not content with this the urchins jump in front of people rushing from bank, office, or shop to catch their trains home and pester them over and over again to buy a paper. What with the roar of the traffic, the clanging of tram bells, and the shrill vociferations of the newsboys, the streets of Melbourne of an evening are not the most pleasant promenades, and I really think some other plan for circulating the papers might be devised… I fail to see why even the Press should be allowed to offer its sheets for sale in such a way as to irritate and annoy people.‘

Other complaints included the peddling of ‘fake news’ to lift sales. It was reported:

Frequent complaints have been made in Melbourne by victimised citizens about the impositions of youths and boys who dispose of newspapers in the streets. It is a practice of certain of the newspaper boys to attract attention by calling out loudly that there is in the paper a full account of some sensational railway or other accident, and then to increase the charge for the paper to unsuspecting customers. Many of the boys have been deceiving the public in this way for a considerable time.

John Quilty, a 19-year-old newsboy, was fined £1 at the City Court in 1914, charged with making a ‘violent outcry in Swanston Street, to the annoyance of the passers-by’. According to evidence Quilty had been calling out “Extra-ordinary edition – account of the Fern Tree Gully railway accident”. The accident was fictitious, but it sure helped sales!

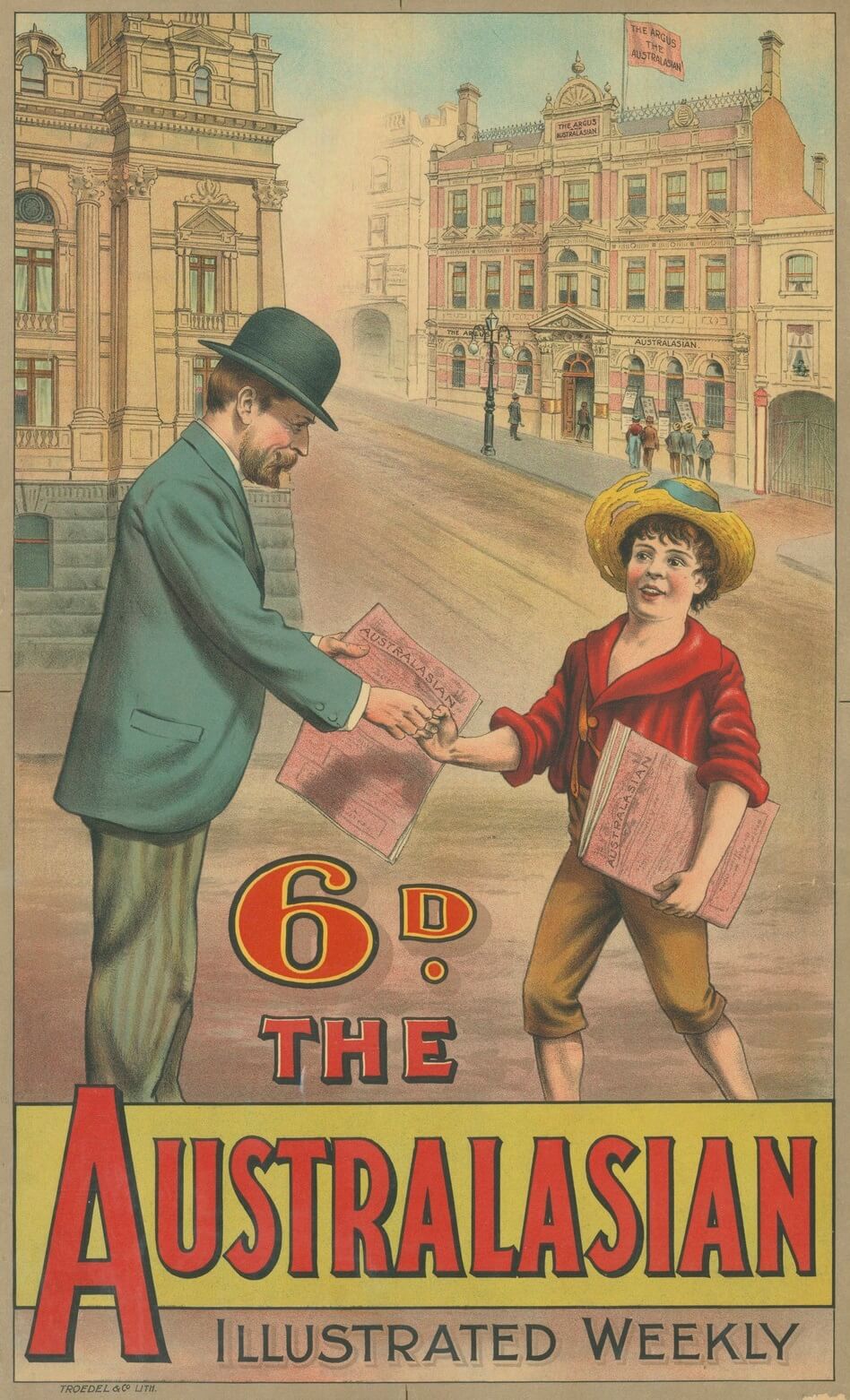

A Melbourne newsboy, in The Australasian Illustrated Weekly, by Troedel & Co., lithographers, c.1881.

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

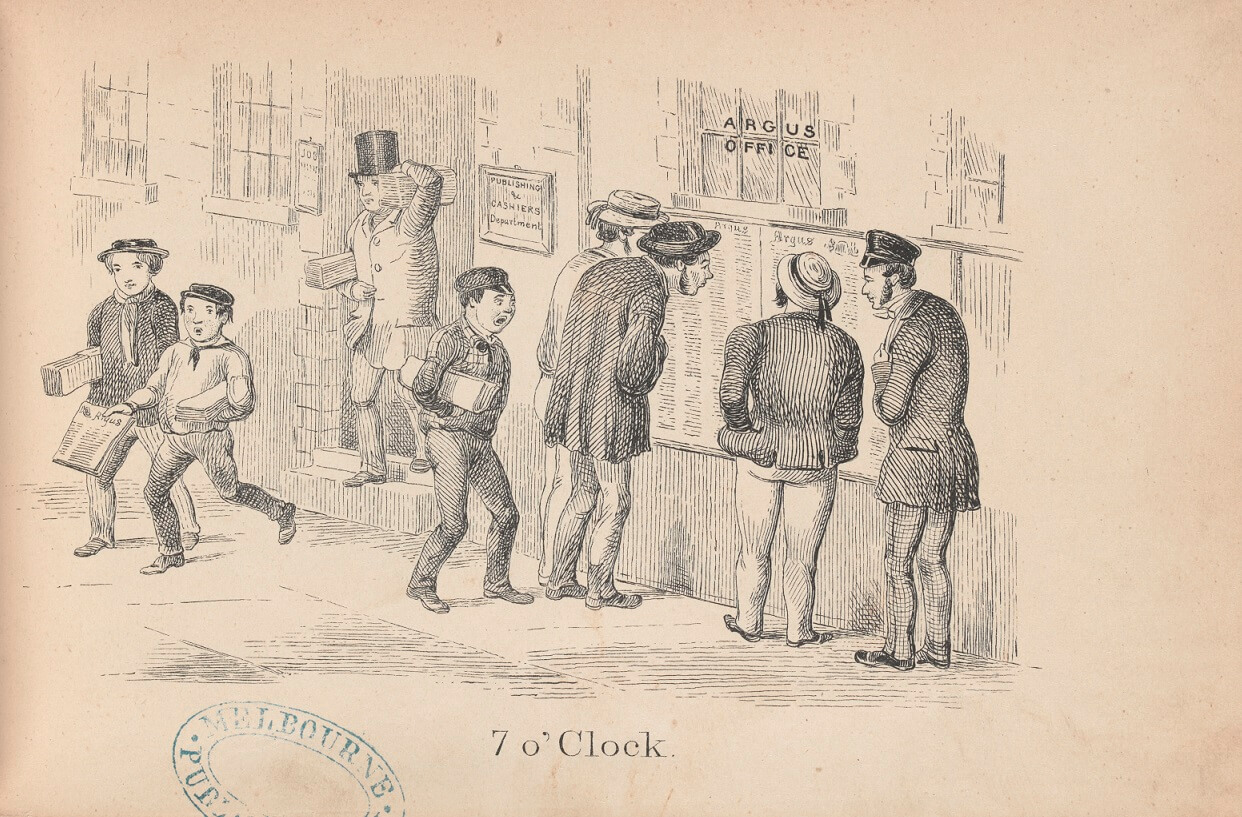

Newsboys, in ‘7 o'Clock’, by Henry Heath Glover, artist, 1857

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

The newsboys’ hour is in the evening, when the stream of traffic is at its height… There are men making for tramcars, men making their way on horseback, men making their way on foot, men hustling each other, women with children by their side, women with parcels in their hands, people of all sizes, ages and conditions talking, hurrying, gesticulating, surging, swaging (sic) to right and left… In the heart of the press the newsboy plies his trade, and earns his living. He is heard above the roar of traffic, and his assertiveness is something that cannot be gainsaid. He is there to earn a living, and he earns it. On the right he dodges sudden death in the shape of a tram-car, and on the left he thrusts a paper into the hands of a passer-by… He sells his wares while the crowd is struggling for an opening, and the police are trying to clear the streets. He is in his small way the protagonist of the whole drama, the sprite of the whole stormy scene.

Lyttelton Times, 7 January 1899

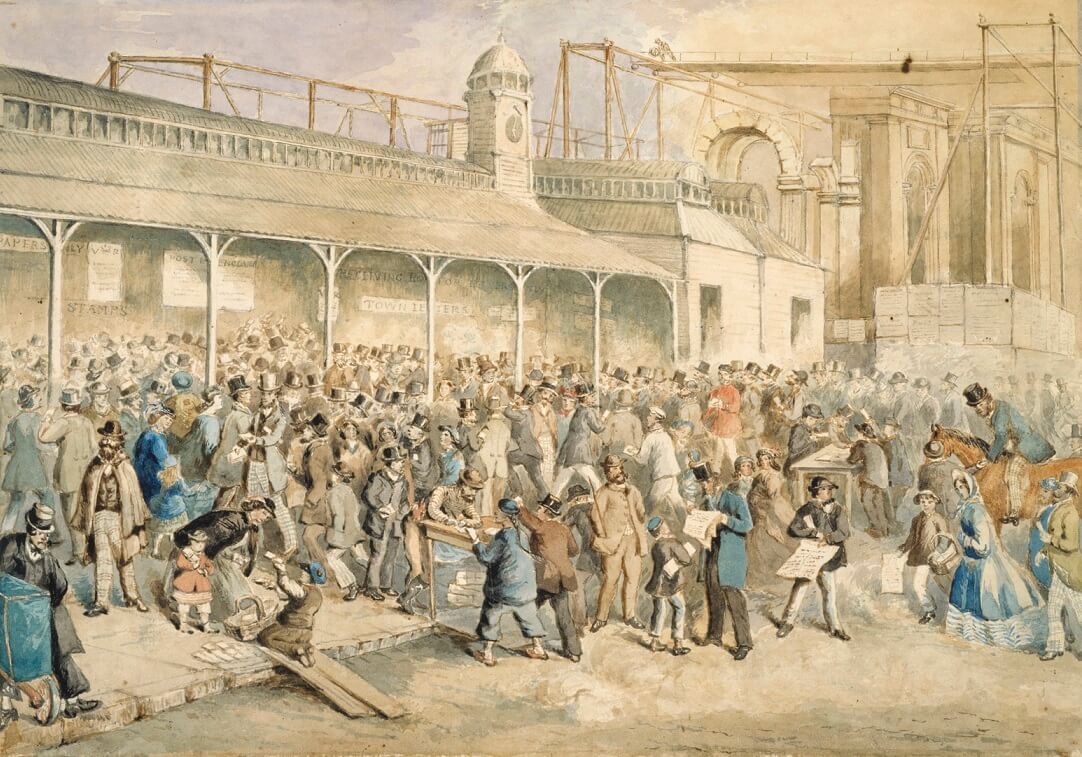

Newsboys peddling papers in ‘English mail day at the Post Office, Melbourne’, by Nicholas Chevalier, artist, c.1860

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

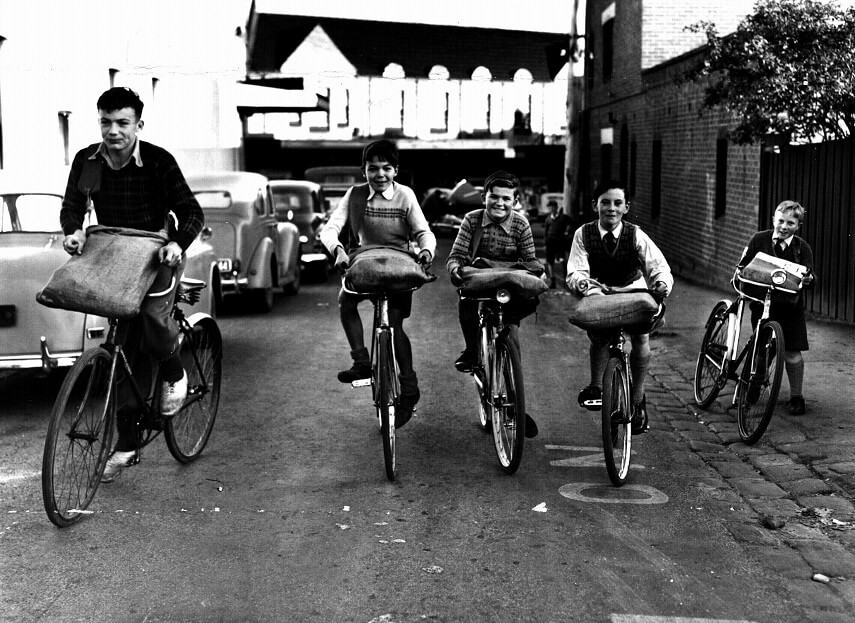

Newsboys Leon Wiegard, Wally Leckie, Kenneth Brian White, Paul Wenn and Brian Galley leaving for their rounds, by unknown photographer, 28 May 1954

Courtesy Herald Sun newspaper

Selling newspapers became an important source of extra income for many working-class boys from the city and inner suburbs. Within living memory are boys doing morning paper rounds - in all weather, on foot or bike.

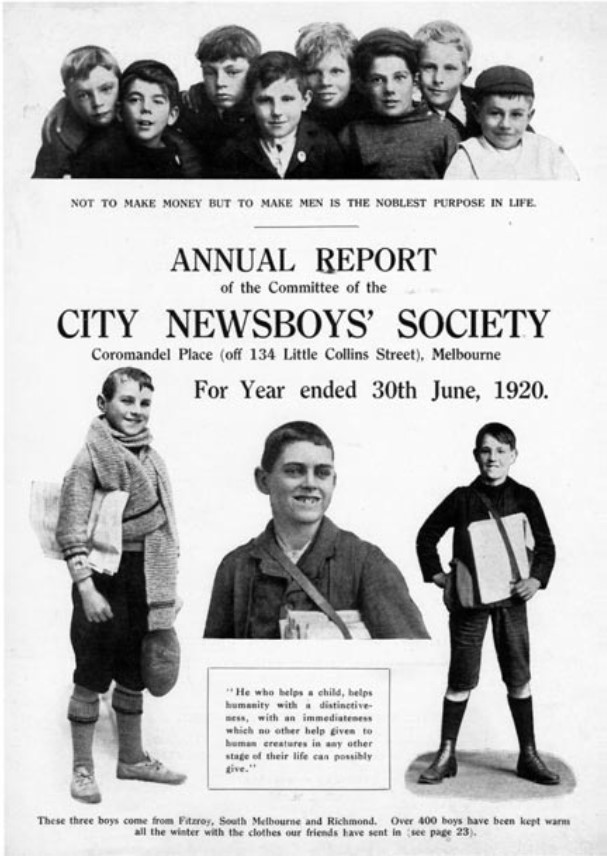

City Newsboys’ Society, Annual Report, 1920

Melbourne Newsboys’ Club Foundation Records. Reproduced courtesy La Trobe Australian Manuscripts Collection, State Library Victoria

One of the largest boy rescue societies in Melbourne was the Newsboys’ Try Society (later City Newsboys’ Society), founded by William Forster in the late 1880s. Boys paid a membership fee to join the Society, allowing them to choose a range of classes such as carpentry, boot-repairing, printing, writing, shorthand and book-keeping. The society aimed to ‘improve the social, moral and spiritual condition of underprivileged boys and to redirect their energies into worthwhile directions.’

Forster was a prominent ‘child rescuer’. For years he appealed for proper licensing, demanding that newsboys’ work be regulated. He was regularly consulted over child wellbeing and protection laws, notably the 1887 Neglected Children's Act. Forster recommended that children under 10 should be prohibited from pursuing casual employment in the streets after dark – ‘It is after 8 o’clock that the scenes occur witnessing which taints and corrupts the child’s mind’.

The age of street workers, the irregularity of their lives and their lawless environment concerned Forster. He was quoted in the Spectator in 1899:

[The newsboy] lives during the day in the streets. His hours of labour commence with the issue of the evening papers, and for the greater part of the day, if uncared for, he would resort to the alleys and by-ways.

Then there is the army of waifs, too often the children of drunken and dissolute parents, who gain a precarious livelihood by selling matches and other trifling commodities. All these areas reached by the City Newsboys’ Try Society…

On a cold, wet day, the little scantily-clad newsboy, who wears the Society’s badge, knows where he can obtain food, rest and shelter at a nominal charge, if he can pay it, and for nothing of he has not the penny asked for, while hot baths are filled up for his use.

Link to article, From “Try” Boy to Diplomat in Societ Russia, The Argus, 13 February 1943. Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia

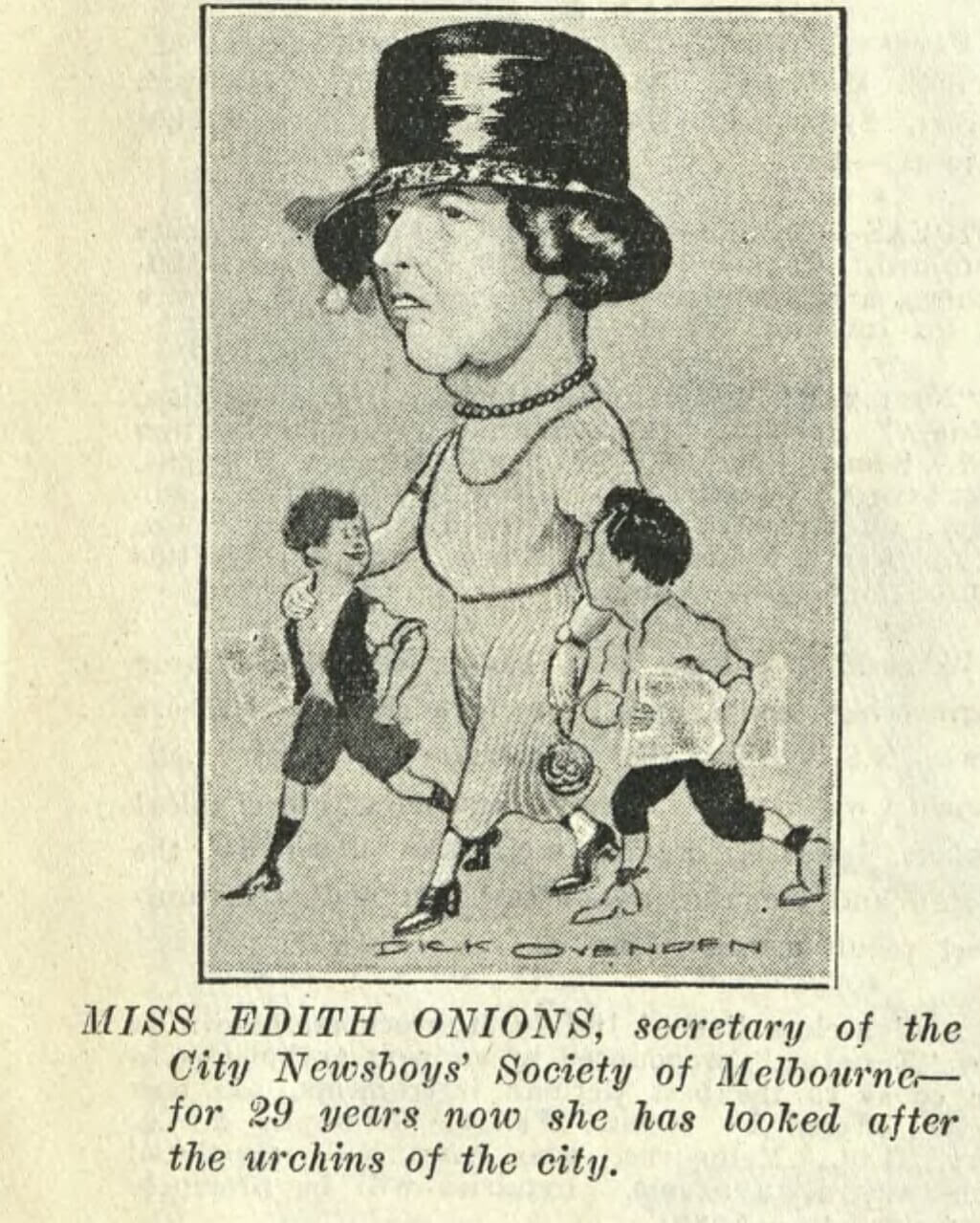

Mrs Edith Onians

Edith Onians, the ‘Newsboys’ Friend’, c.1945

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

The Bulletin, Vol. 46, No. 2352, 12 March 1925

Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia

I believe sincerely that no boy … is irreclaimable. Every youngster … born into Australia is a potential source of wealth and happiness [and] is capable of being turned, by appropriate treatment, into a useful citizen … Doubt paralyses; only certainty achieves.

Edith Onians, in Read All About It, 1953

Because I am so happy I have come to the conclusion that the happiest people in the world are those who seek to serve others. For, in trying to help others, I have often found my own sorrows and problems dwarfed by the larger issues I have seen around me; so that often I have found myself more helped than helping.

Any true service spent for others I find is returned with the measure pressed down and running over, and it seems to me that few are more appreciative of work done in their behalf than the boyhood of today.

Service without love to me is a barren thing, for “the milk of human kindness, if it is to nourish, mush be full cream, not skimmed”.

Edith Onians, in The Herald, 9 July 1936

Edith Onians (1866-1955) began volunteering at Forster’s Newsboys’ Society in 1897, teaching English to a group of illiterate newsboys. She remained at the organisation for 58 years, as its honorary organiser and secretary, becoming known as the 'newsboys' friend'.

A single woman with independent means, she devoted herself to the organisation. Under her leadership the Society expanded to include education, training and leisure activities, coupled with counselling and relief. She instituted a savings bank, free medical and dental care, welfare assistance and a country holiday-home for impoverished mothers of newsboys. Newsboys were provided cheap and hot meals, and access to second-hand clothing. Onians had the contacts and energy to attract funding from private donors, although the Society also received some government grants.

Facilities at the Society’s ‘club-house’ in Little Collins Street were extensive. The Age reported in 1929:

The club is divided into two sections – one, for bettering the boys’ education, the other, to provide them with healthy recreation, and for both work and play the club is wonderfully equipped.

More than 20 classical and technical subjects appear on the educational side while, from a recreational point of view the club caters for nearly every popular sport.

Apart from mechanical equipment – metal and wood lathes, carpentry, electrical and wireless workshops – the club has a magnificent gymnasium and swimming pool, a huge library and reading room and a dozen other up-to-date facilities.

Onians believed in every child's potential, whether rich or poor. Not all members of the Society were newspaper sellers. For example, in 1929 out of 254 members only 90 sold papers. As Onians put it:

Our building is open to all boys who want somewhere to go in their leisure hours. The object of the City Newsboys’ Society is to help the boys to lead useful lives and to become self-supporting by teaching them trades.

Onians herself was described as an ‘ageless, forever-moving little woman with silver hair, twinkling eyes and witty tongue’ – and she claimed to never forget a boy’s name. She ran the society ‘not with a rod of iron, but with love’. And the boys loved her back:

“Miss” knows no time clock, she goes in at 9 a.m. and goes home when there’s no more to do for her boys and for it all she is not paid a single penny. “My boys are reward enough, a thousand times over”, she says.

To further her knowledge of child welfare, Onians travelled overseas in 1901, 1911 and 1929, visiting boys’ clubs, children’s courts and other child-saving organisations. She reported on methods used in England, Europe, U.S.A. New Zealand and Scandinavia.

Like Forster, Onians pushed for legislation aimed at the care and protection of working children in Victoria. For years she agitated for the licensing of young street traders, particularly newspaper sellers. When the Street Trading Act came into force in July 1928 Onians was the only female member on its board. In 1933 she was appointed an O.B.E. The following tribute was printed in The Weekly Times:

In paying his tribute, one “Old Boy”, with a long memory, went back to his childhood days:

“I have always felt that when the King became aware of your work he would be pleased to honor you, Miss”, he wrote. “Perhaps you will remember when I was a little boy you told me that you had sat next to the King at a big gathering. So I said to you, ‘What did he say to you, Miss?’ You replied. “Oh, the King wouldn’t take any notice of me, as he has never heard of me”. To that I said, “Well, Miss, if he knew who you was he would be glad to speak to you”.

Onians was still working with the Society when she died in 1955. The Argus reported her death:

Miss Onians was responsible for building the City Newsboys’ Society into one of the world’s finest boys’ clubs.

Yesterday boys with bowed heads paid tribute to the woman who for over half a century was their protector and friend and became affectionately known to them as ‘Miss.

The Age ran the story, ‘”Mother” to Newsboys’:

Although failing health prevented her from devoting as much time to the club as she would have liked in the past 12 months, she often called to see how her boys were faring.

She knew most of them by name or nick-name and counted clergymen, doctors, Cabinet Minister and prominent city businessmen, all of whom had been newsboys, as her friends.