Before the gates could be opened to road traffic, I had to phone Broadmeadows and Craigieburn signal boxes to find out if a train had left or was about to leave either station. If a train was approaching, the gates would remain closed, as trains had priority. This often meant a wait of a few minutes for the road users and I would happily chat to the drivers, who were usually patient and accepted the delay without rancour. If no trains were due, then I moved the train signal to Stop, unlocked the gates and pushed them open.

Thomas E. Yates, What a Journey: Life in the Victorian Railways 1948-1987, 2004

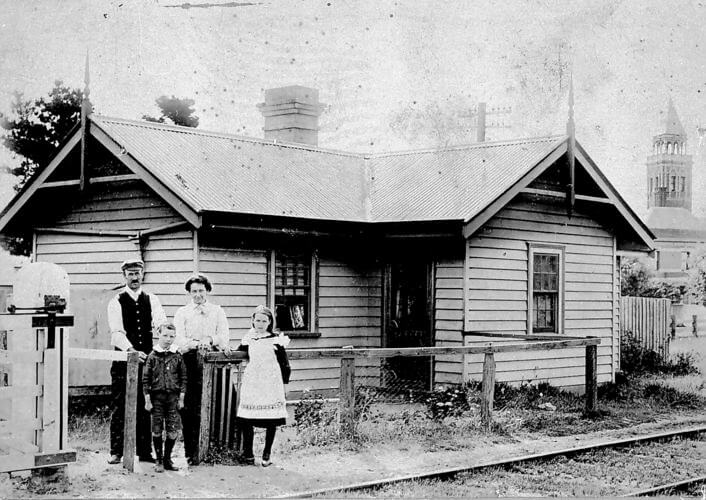

Gatekeeper, Rod McLean, with his family beside the wooden gates of a railway crossing. The small weatherboard cottage behind them may have been be a residence provided by Victorian Railways.

Reproduced courtesy Museum Victoria

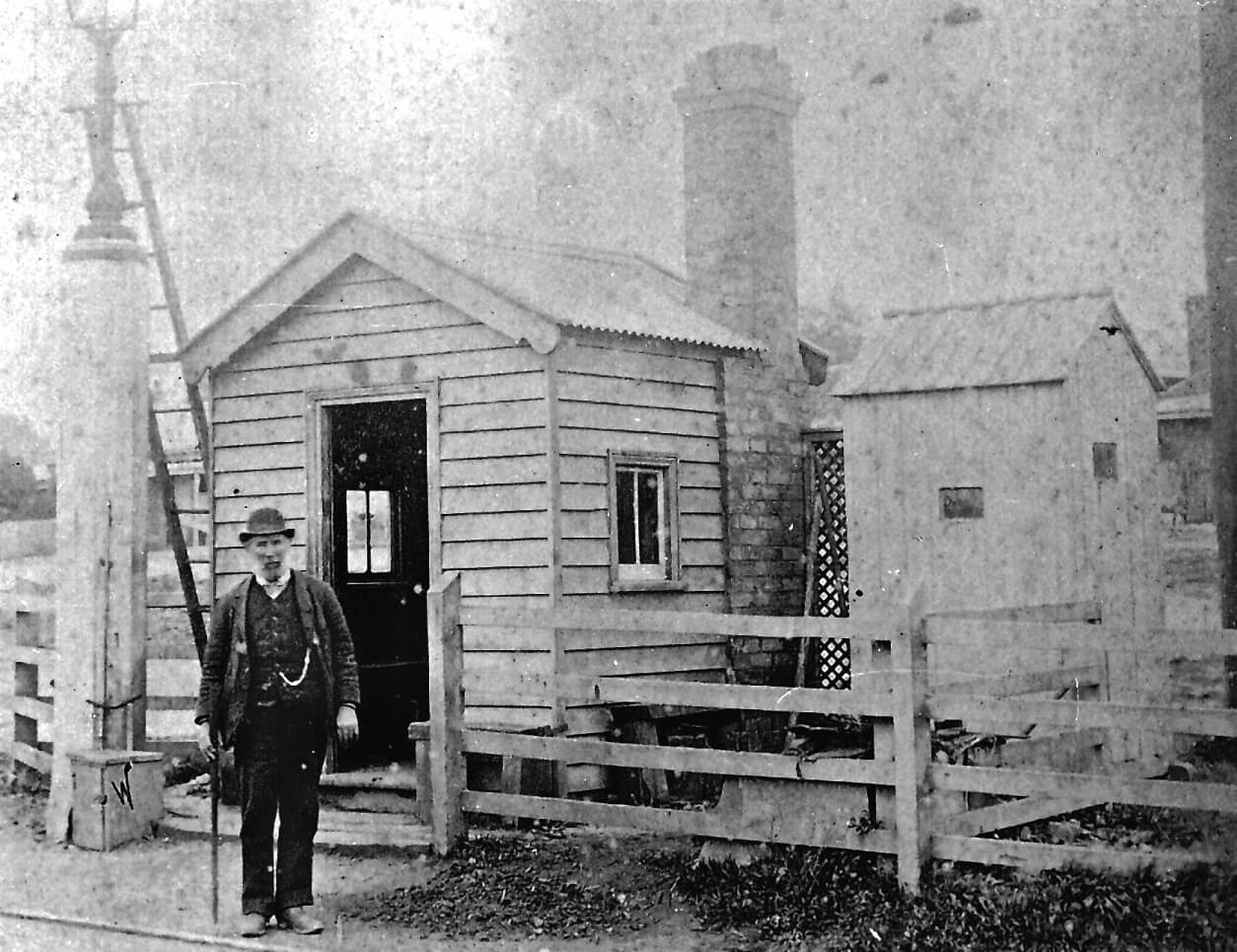

Gatekeeper at Doveton Street railway gates, c.1900

Reproduced courtesy Museum Victoria

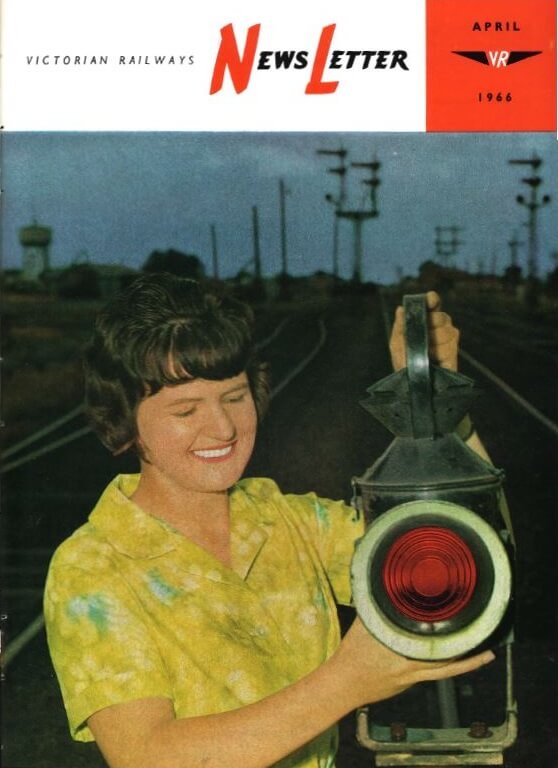

LADY WITH THE LAMP is Assistant Gatekeeper Carmel Scanlon, shown placing lamp on crossing gate at Horsham station. Although Miss Scanlon has been in the Department for only 17 months, she was recently commended for her vigilance in detecting and reporting a hot box on a passing goods train. Her parents, who are also gatekeepers at the crossing, came to Horsham recently from Dimboola.

For many years level crossings were protected by manually-operated gates, closed as a train approached and re-opened afterwards. A gatekeeper was employed but it was a poorly-paid job, most gatekeepers earning little more than a ‘Lad Labourer’ at 4 shillings per day.

Some gatekeepers had free housing at the crossing but had to operate the gates at all hours. Night work was the most trying time. After the last train had passed the gates were locked to road traffic, but the gatekeeper (or his wife and children) had to be prepared to jump out of bed and let a car through:

It’s amazing how people will persist in selecting the darkest and wettest nights to go home late by car”, says the gatekeeper musingly. “Springing out of a warm bed in the early hours of a winter morning, tossing on a few clothes, and stumbling out into the cold to open the gates for a carload of drunks isn’t much of a joke, you know”.

By the 1920s a number of women were employed by the Victorian Railways as gatekeepers. The job was given to the wives of railway employees, or widows with children. It was a meagre charity: the women worked long shifts, sometimes more than 12 hours per day. They were poorly paid, often having to take in washing to ‘help fill the larder.’

Living (and working) so close to the railway lines was dangerous and, tragically, a number of women gatekeepers lost their lives. Mrs Morris was struck by a train and killed in Bendigo in 1913. Mrs Brady, gatekeeper at Brighton Beach, was killed in 1918. According to information supplied by police, Mrs Brady saw the approaching train and noticed children on the line. She rushed from her cottage to give the alarm, and while she was doing so, was knocked down by the incoming train.

Jessie Robinson was another fatality, killed at the age of 55. She had worked the Balcombe Road crossing at Mentone for 24 years. The Moorabin News reported:

Last Saturday, about 9 p.m., a serious accident occurred at the Balcombe road gates, whereby Mrs Robinson, the gatekeeper, was instantly killed. Employees of the Colonial Ammunition Company had been holding a picnic during the day. One trainload had left for home, and at ten minutes to nine a special train pulled into the station… Thinking that she had time to let the vehicles through before the train started back, Mrs Robinson opened the gates. Whilst closing the gates, the train dashed into them, and knocked Mrs Robinson over, the wheels severing the head from her body.

Sad coincidence surrounds Mrs. Robinson’s death. Her husband, a guard in the department’s service, was killed in a railway accident at Bendigo some years ago. For 24 years the widow had been in charge of the Balcombe road crossing, but this was to be her last week on duty, as it was expected that the interlocking gear connecting the gates with the new signal-box would be finished in a week. The deceased had received notice of transfer to gates at the other end of the station, in fact, a considerable amount of her furniture was packed ready for removal.

At a later inquiry Coroner, R.H. Cole, criticised the vigilance of the train’s guard and local signalman. He also questioned the Railways’ policy of employing a woman to handle such heavy gates:

Here is a woman 55 years of age, in charge of heavy railway gates, which it is intended to make interlocking gates, and this woman is left in charge of these gates for seven hours on end during the busiest part of the day. The Railway Department should have put men in charge of these gates instead of leaving a woman alone to work them.

When it was remarked that many of the gatekeepers were appointed as a kindness to relatives of employees who had died or been killed while in the railway service, Dr Cole replied:

Kindness! Do you call it kindness to give a woman these heavy gates to work at four and sixpence a day? I do not think the Railway department should be economical at the expense of the safety of its employees.

Jessie Robinson was much admired at Mentone, both for her personable manner while manning the gates and for her bravery. In 1896, at the risk of her own life, she had saved a young girl named Emily Huckett from certain death:

The little one was too frightened to stir, and stood on the track as a train was running into the station. Mrs. Robinson rushed to the spot and snatched the child up just in time.

In the same year she performed another ‘conspicuous deed of bravery’. The Barrier Miner reported:

A boy named Buckett got on the railway line, whereupon she jumped in front of an approaching train and rescued him. So close, however, was the train that her apron was torn off by the engine.

After her death a committee was formed to collect subscriptions for a suitable memorial. Donations were used to purchase a memorial tablet that was erected over her grave at the Williamstown Cemetery.

Kitty Windsor - gatekeeper

In 1923 Ernest (Ernie) Windsor arrived in Melbourne from Manchester looking for work. He found work as a farm labourer at Rockbank. Several months later his wife Catherine Windsor joined Ernie with their two children Catherine (Kitty), born 1919, and Dominic (Dom), born 1922. Catherine also worked and lived at the farm cooking and cleaning. They both worked very long hours, which was very hard with two young children. Eventually Ernie found a better paying job working on track maintenance with the Victorian Railways at Yarroweyah, near Cobram. The town of Yarroweyah consisted of their railway house, an unmanned small railway station, a one-roomed school, and a shop; the rest of the town was farmland. They stayed there for ten years during which time two boys were born, John Ernest (Ernie) and Augustin (Gus/Megs). There was no work for women in the area and as Kitty was fourteen, and Ernie was able to transfer to the North Melbourne railway yard, they decided to move to Footscray. The first night that the children spent in Footscray was amazing to them as they had never seen the big lights of the city. Kitty found a job at Kinnear’s Rope Works.

When a position, which included a railway house, became available, the family moved to Tunstall (now Nunawading). Kitty and her mother were employed as gatekeepers at the Springvale Road level crossing and Ernie as line repairer between Ringwood and Box Hill. The level crossing gates were constructed from solid hardwood with steel braces. The gates were extremely heavy which made them hard to push especially in windy weather. There were four in total. The gatekeeper position was split into two twelve-hour shifts. Kitty often worked fourteen hours and at times she would work sixteen shifts to ease the burden on her mother – especially when her young sister Patricia was born. After finishing his shift on the track, Ernie would also do several hours working the gates.

Part of the second shift was between midnight and 6am. During this period the gates were locked in position to allow maintenance trains generally spreading ballast to come through. If a car at night needed the gates opened the driver would knock at the gatehouse next to the line and the willing person would go out in the freezing cold, open, and then lock the gates again. There was a little hut by the gates with a small fireplace. There Kitty could take shelter from the cold or the hot sun, but most of the shift would be spent outside.

While watching for trains she would crochet beautiful dresses on order for local women. During the war years she turned her crocheting skills into producing camouflage nets for the war effort. The family also entertained soldiers from the army camp situated beside the railway line, with Catherine playing her pianola for a singalong. Kitty knew every person in Tunstall, as they passed through the gates, they would always say hello.

For all the hours she worked, seven days a week, she only received two weeks’ holiday and no superannuation, as that was for males only. Kitty left the gates in 1950 to marry Frederick Cottle, whom she had known since she first arrived in Tunstall.

Text written by Fred Cottle, Kitty’s son. Reproduced here with his permission.

Kitty Windsor (pictured) and her mother were employed as gatekeepers at Tunstall (now Nunawading) in the 1940s. Her father, Ernie, maintained the track between Ringwood and Box Hill.

Kitty worked 14 hour shifts, sometimes longer, to ease the burden on her mother. The gates were extremely heavy, made of solid hardwood, which made them hard to push. The constant standing in cold winter weather caused chronic chilblains on Kitty’s legs and feet, for which the doctor had no treatment. Relief came from a surprising source. Once a year a WWI veteran would visit Kitty and sell her a special chilblain cream, which worked wonders. He visited all the gatekeepers in Melbourne, as many of them also suffered from chilblains.

Reproduced courtesy Kitty’s granddaughter, Rachael Cottle