Trains, tracks and stations are an integral part of our landscape, linking past and present. Those who worked the railways, however, tend to be forgotten. Where they are remembered — often in coffee-table books celebrating the steam age… they are usually stereotyped as whistle-blowing driver, flag-waving signalmen or cap-donning station masters. Colourful though they may be, these images convey nothing of the complex reality of working on the railways.

Eddie Butler-Bowdon, In the Service? A history of Victorian railways workers and their unions, 1991

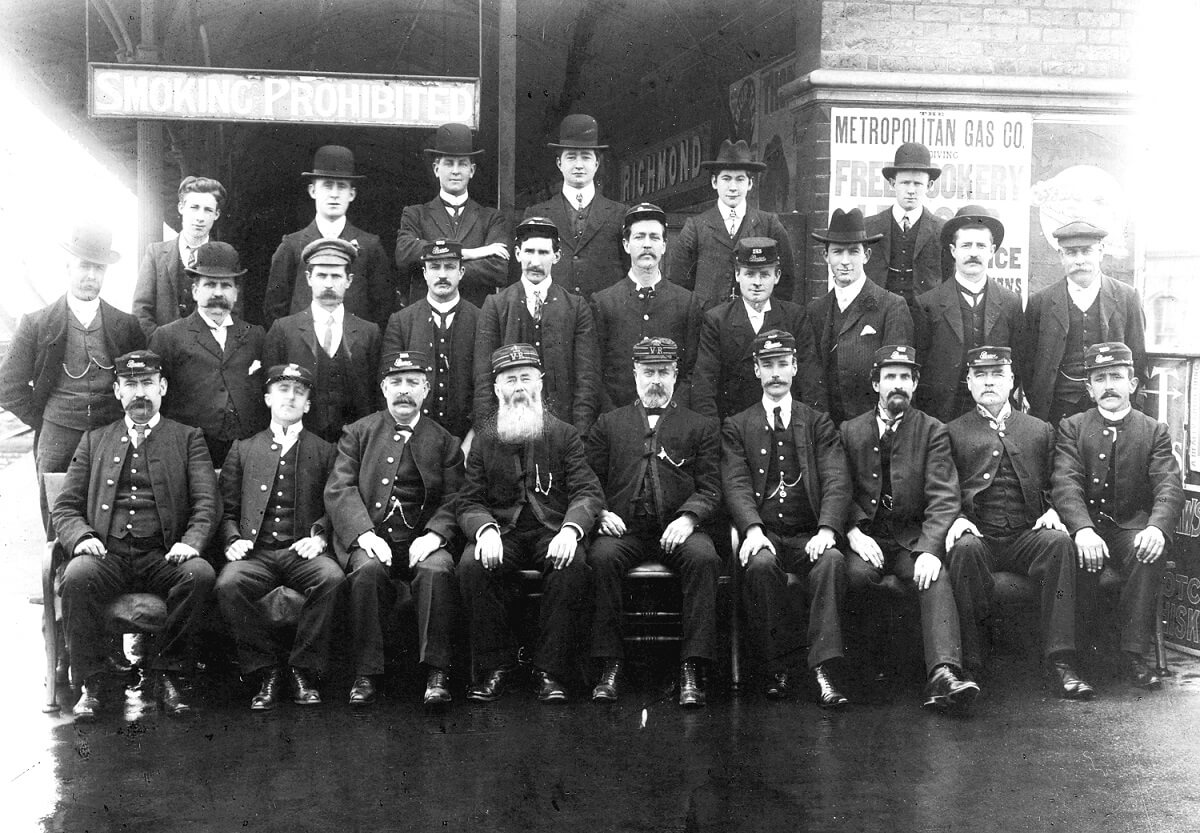

Station staff, Richmond, c.1890

Reproduced courtesy Public Record Office Victoria

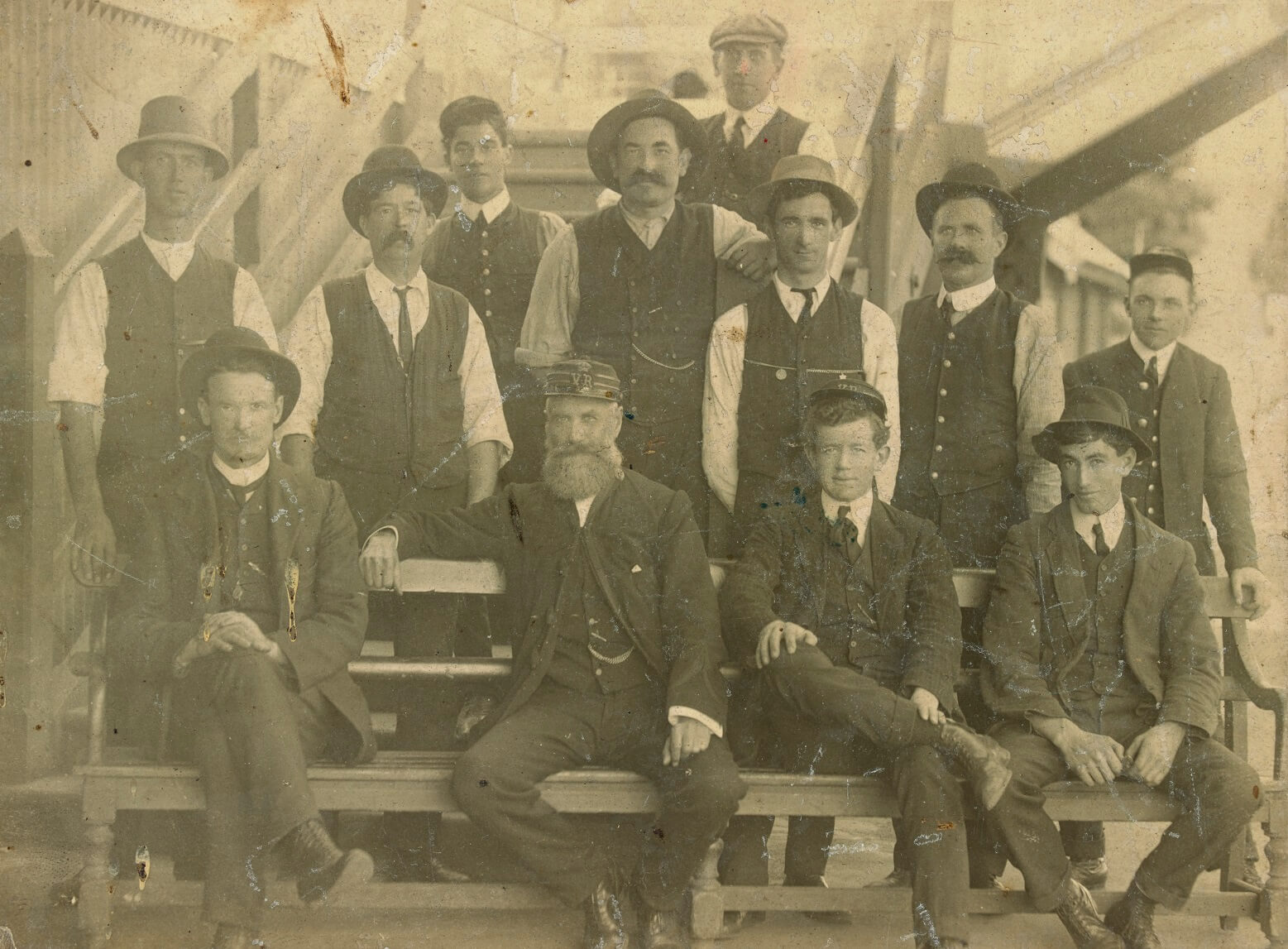

Whittlesea Station and staff, c.1890s

Reproduced courtesy Public Record Office Victoria

Station staff, Woodend, 1910

Reproduced courtesy Public Record Office Victoria

Railway jobs have disappeared with increased automation and road transport, and perhaps the greatest impact has been on station staff. Until recently they performed duties ranging from ticket-collecting and sales, to cleaning and bag-handling. In the 1970s there were 76 staff at Frankston Railway Station, working rotating shifts— a Station Manager, Assistant Station Manager, clerks, signalman, guards, parcels and yard assistants, station assistants, carriage cleaners and a ladies’ waiting room attendant.

New technologies, different market conditions and changing management practices have altered the number and nature of the tasks to be done. Ticket-machines allow many stations in regional and metropolitan areas to be unmanned. The role of country Station Master no longer exists, with a single station manager responsible for several stations or an entire branch line. Well-tended station gardens and attractive waiting rooms linger in the memory only.

Station Master, Mr Valli, photographed c.1928

Reproduced courtesy Public Record Office Victoria

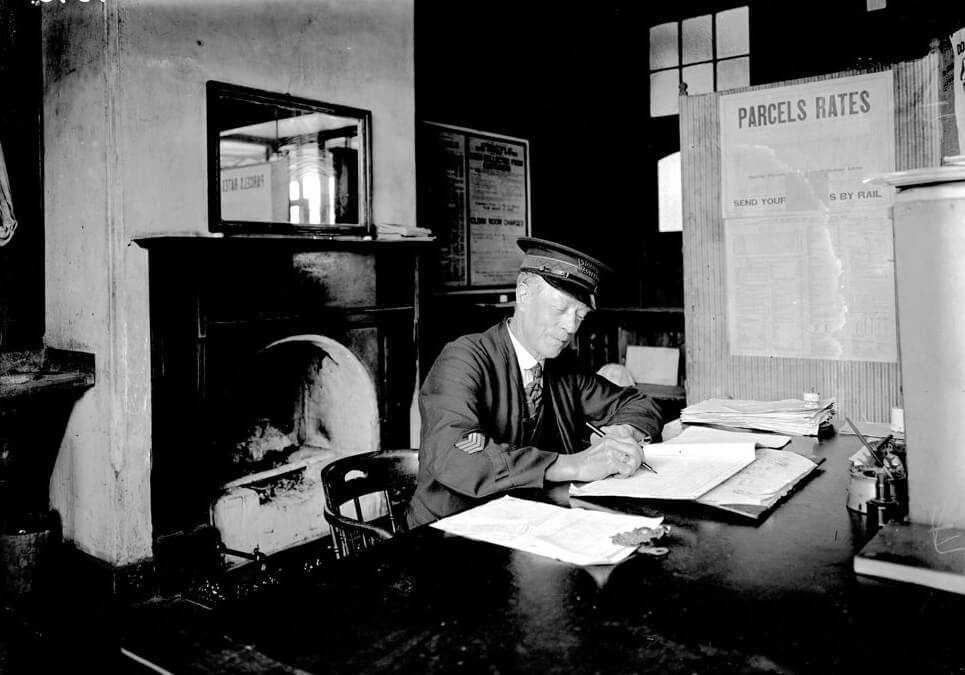

Station Master at work in his office, Macedon Station, c.1928

Reproduced courtesy Public Record Office Victoria

Until quite recently, large terminus stations and small country branch line stations were managed by Station Masters. The Station Master (SM) was responsible for all railway operations including the staff, train running, yard shunting operations and all financial balances. Harold Clapp, Chairman of the Commissioners of Victorian Railways in the 1920s called stationmasters ‘his front line soldiers’.

The position, with enormous responsibility, went to outstanding employees. The following instructions issued to Station Masters in 1876 were explicit:

The Station Master shall always communicate his instructions in clear and precise terms. He shall keep himself thoroughly acquainted, by constant personal intercourse, with the character and conduct of every man under his control, and maintain discipline and order… He shall enforce regularity, order, cleanliness, and neatness throughout the Station, keeping it clear of weeds, the ballast raked, and nothing left lying on the surface which is not properly there. Every article must be kept in the place appointed for it.

The public profile of the Station Master gave him a certain prestige, rivalled only by the engine drivers. In the country especially, the Station Master was a well-respected figure with significant social standing in the local community. He was provided with a station house to live in and often sought out for advice, particularly on bureaucratic matters, such as how to fill out tax returns!

Station Master Mr Foster and family at Middle Creek, 1931

Reproduced courtesy Public Record Office Victoria

Porters, Tulloch and Holmes, and Station Master, H. Pithec, at Lancefield Junction Station, 1890

Reproduced courtesy Public Record Office Victoria

Porters assisted the movement of heavy items around the station, either goods and parcels to the guard’s van, or passengers’ luggage to the train — all part of the service once provided to travellers.

Portrait of Victorian Railway porters, unknown station, c.1890

Reproduced courtesy Public Record Office Victoria, VPRS 12800/P1, item H 1696

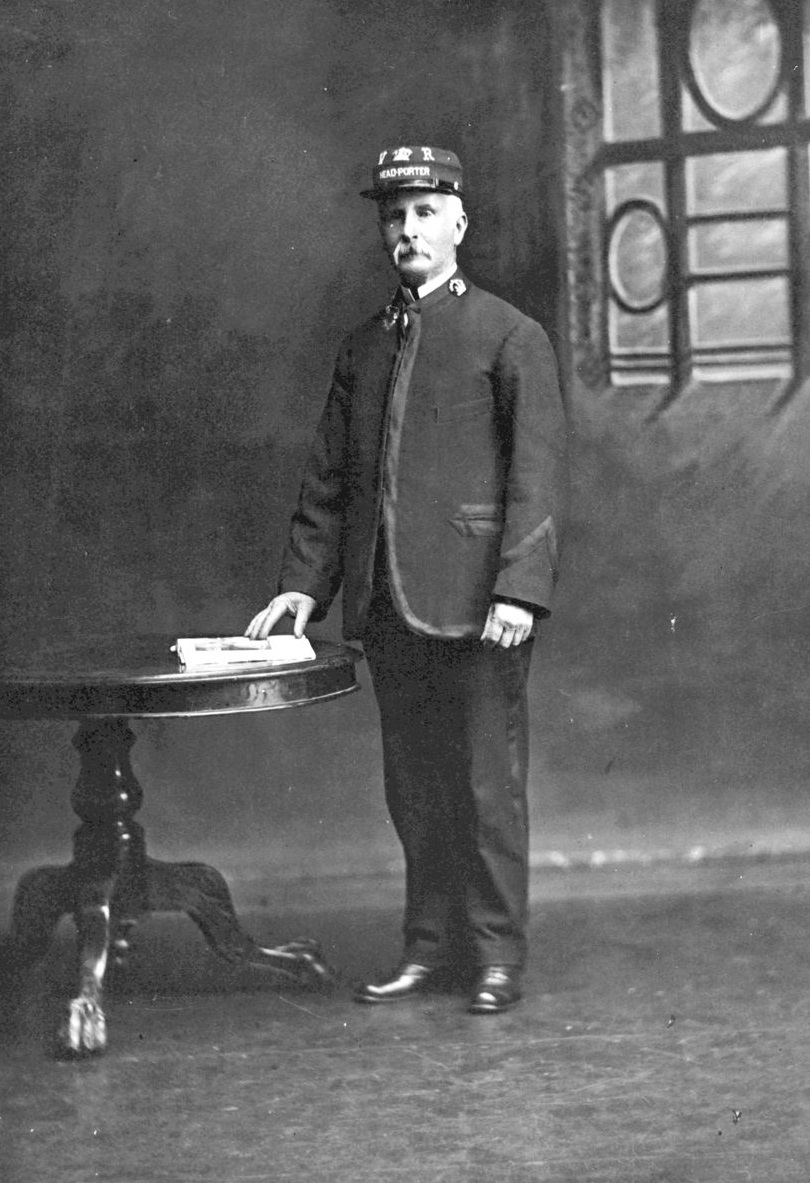

Mr George Morris, Head Porter at Maryborough Railway Station for ten years, from 1890 to 1900

Reproduced courtesy Public Record Office Victoria

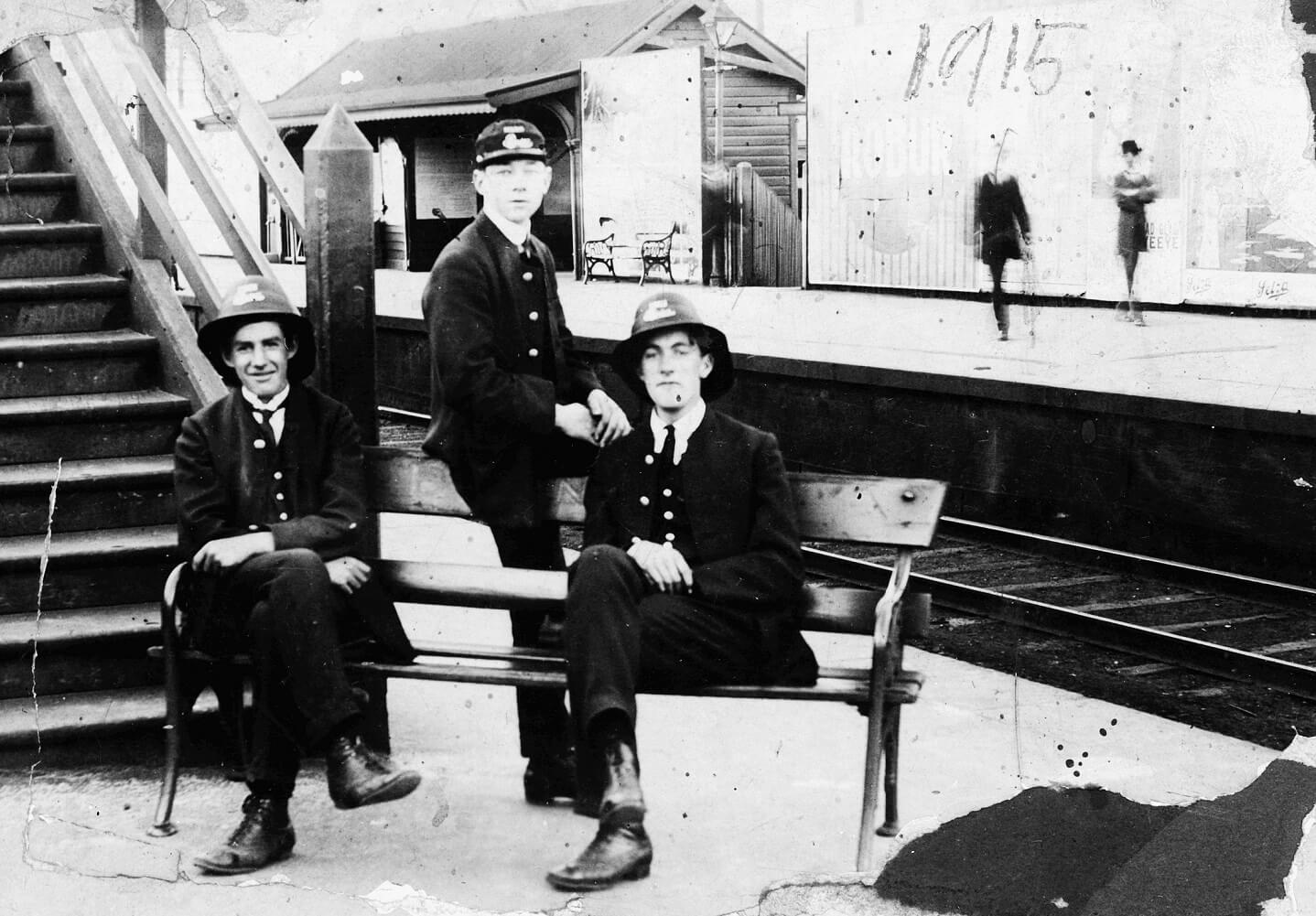

Lad Porters, W. Noble, L.R. Bewry and A. Knight, at Burnley Railway Station, 1916

Reproduced courtesy Public Record Office Victoria

A typical career progression would see a porter advance to become a head porter, then a ticket collector or booking clerk, which could lead to the senior roles of assistant station master or station master. Boys as young as fourteen were employed as ‘Lad Porters’, the most junior grade of station staff.

The role of porter was taken over by female workers during the Second World War. Victorian Railways employed female porters and ticket collectors from June 1942. The ‘manpower shortage’ during WWII allowed women to undertake heavy manual labour, previously considered to be unsuitable.

A baggage porter assists a female passenger at either Flinders Street or Spencer Street Station, c.1940

Reproduced courtesy Public Record Office Victoria

Photograph of a female railway porter employed by Victorian Railways, c. 1944

Reproduced courtesy Australian War Memorial

At 14 I joined the Railways as a lad porter at 2/- per day. Employment was hard to get and to qualify for a Lad Porter it was necessary to pass Board of Selection, Medical, Eye & Ear, Educational, before being appointed to the permanent staff. No uniform was provided, but if you desired to purchase one it was made to measure at Lincoln & Steward for 28/4 — 3 piece — buttons and all.

-J.H. McCarthy, ‘Early Days with the Victorian Railways’

Station Officer changing the indicator clocks at Flinders Street Station, c.1960

Reproduced courtesy Public Record Office Victoria

This is a photo of Steve taken in the 1960s. Steve was the man who turned all of the clocks to the departure times with his long pole… Steve was probably one of the busiest workers at the station during peak hours.

Michael Binney, quoted in Jenny Davies, Beyond the Façade: Flinders Street, more than just a railway station, 2008

Automation has made many railway jobs unnecessary and obsolete. Clocks at Flinders Street Station show the departure times of the suburban trains and, until 1983, were changed manually by a railway officer using a long pole to turn the hands through the base of the clock. During an eight-hour shift, the clocks would be changed 900 times!

The railways planned to replace the clocks with digital displays in 1983, but after a public outcry, they remained in place. They are, however, computer-operated today.

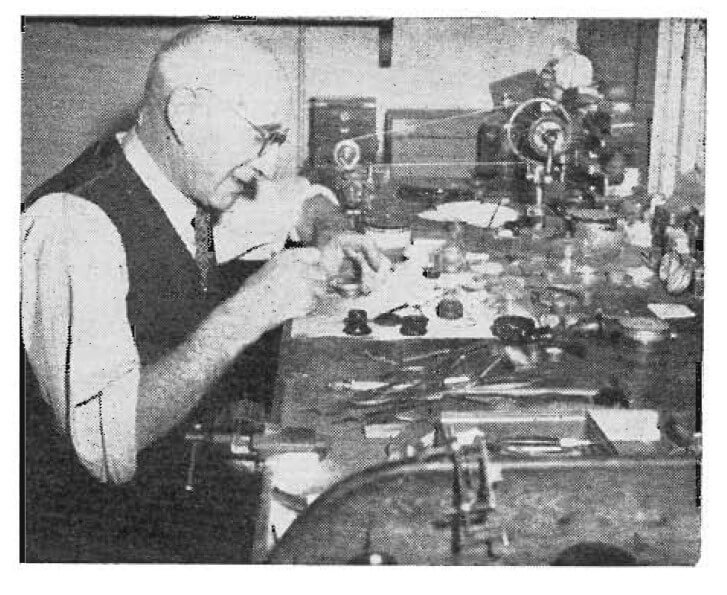

The watchmaker at his work bench

Courtesy ‘Behind the Railway Scene’, publicity brochure published by Victorian Railways, 1950

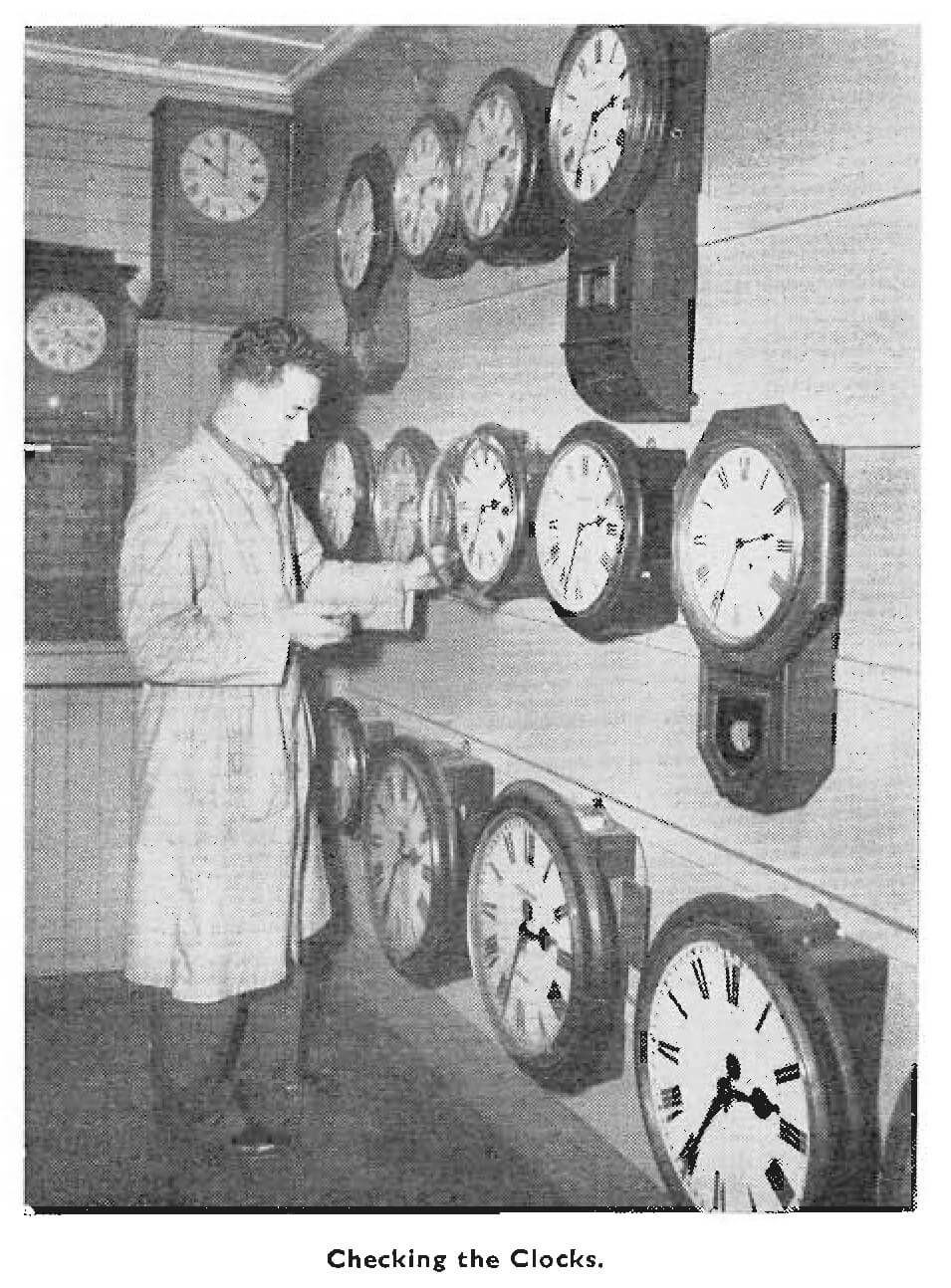

Checking the clocks

Courtesy ‘Behind the Railway Scene’, publicity brochure published by Victorian Railways, 1950

The Watch and Clock Repair room at Spencer Street could well be the setting of an Oppenheim thriller. To reach it, you go into the Station area through the Collins Street entrance. But instead of turning right towards No. 1 platform, or proceeding straight ahead to the suburban barrier, you turn left past the ‘phone boxes. It is inevitable that you steal a furtive glance over your shoulder before slipping down the small alley-way near the fire hydrant, and by the time you have reached the narrow staircase which winds up to the Repair room you’ll be wishing you’d brought a gun. Up the stairs. There’s a door at the top. It opens noiselessly. Inside men are poring intently over a long bench. Clocks – innumerable clocks, tick mournfully on the wall. A den of anarchists, perhaps, busy manufacturing time-bombs? Someone coughs, and you nearly jump out of your skin.

Then the Watchmaker comes over from his bench to greet you, and now you know that here is no anarchist – but a man who creates. For he is an artist, whose medium is springs and cog-wheels, staffs and pivots. He plays no small part in ensuring that railway time shall be the right time. He is the Watch and Clock Repairer – like his father before him.

The largest clock in the service is the tower clock at Flinders Street. You could say it’s also the most important, for it automatically controls hundreds of other clocks. Look at an office, or station platform, or signal-box clock in the metropolitan area, and just above the figure 1 you’ll see two clips. At every hour of the day or night, on the hour, those two clips come down and grip the minute hand of the clocks, drawing it exactly on to the “12”. So if it is a little fast, or a little slow, it is brought automatically to exact time each hour. The controlling mechanism for the operation is in the Flinders Street tower clock.

Looking after that clock is, of course, a big responsibility. It is wound up weekly – and winding it up is some job, believe me! The clock face is eleven feet in diameter…

The Watchmaker and his team do not confine their activities to the suburban area – their responsibilities extend over the whole State. Often one of them goes out to a country station or box where the clock is playing tricks. Or, if the station clock is sent to town for repairs, a spare is supplied in its place.

In railway running, of course, the seconds are important. “On time” means just what it says: not a few seconds early, or a few seconds late. And in keeping the railway time, the Watchmaker and his men render valuable assistance behind the railway scene.

‘Behind the Railway Scene, 1950’, publicity brochure published by Victorian Railways, 1950

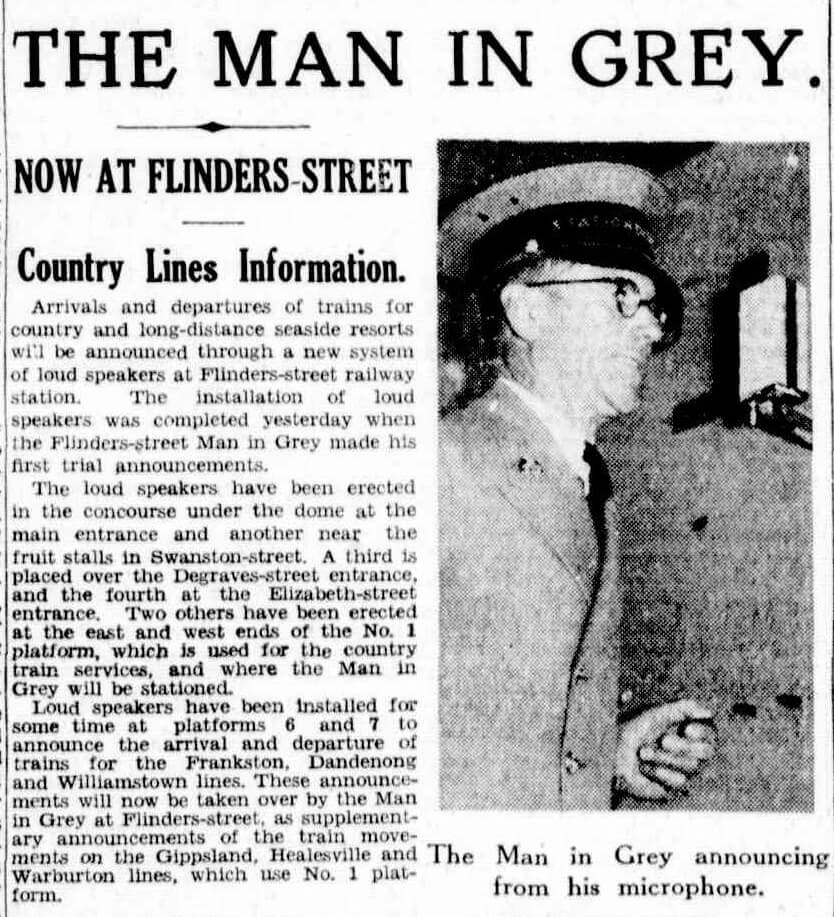

The ‘Man in Grey’ service was available at Flinders Street and Spencer Street stations. The ‘Man’ was hand-picked and specially trained. He was available to answer questions and give assistance to passengers, usually about train times, fares and platforms.

‘The Man in Grey now at Flinders Street Station’, The Age, 17 June 1937

Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia

Besides a ‘pleasant and affable manner’, he had a prodigious memory for timetables and services and would ‘take time off to explain everything in detail to all-comers… to drunks, from fuddled foreigners to earnest and garrulous old women, from temperamental musicians to giggling girls.’ In 1937 the Man was given a public address system at Flinders Street Station, with a loud speaker on each platform. During World War Two, when troops were leaving Flinders Street to travel to the Broadmeadows Army Camp, the Man would call out a solemn ‘good luck boys’.

The Man in Grey service ended in the 1970s.