The 1930s were the heyday of Victorian Railways, but after the Second World War branch lines and passenger services contracted and then disappeared. Between 1978 and 1987, 56 country lines were closed entirely.

These closures, combined with the introduction of modern technologies, dramatically reduced the railway workforce. For example, in 1915 Melbourne was the first Australian city to electrify its suburban railway network with immediate economic benefit. On the St Kilda line, ten crew, working five electric trains, offered comparable service to the twenty-one crew, eight locomotives and six trains required in the days of steam. From the 1950s diesel replaced steam. Diesel trains had smaller crews, did not need to stop for water and ran for days without refuelling. Unlike steam engines, they required little routine maintenance.

Labour-saving techniques have been introduced in many areas, including the workshops, and track repairers, a familiar sight in earlier times, have been largely replaced by machines. Centralised signalling has replaced the signalmen who were needed at each junction, siding or crossing loop and automatic boom gates have made the role of ‘gatekeeper’, once in charge of the gates at a level crossing, obsolete. Technological advances have been accompanied by reduced dependency on rail transport. Trucks now compete with trains for long distance haulage and, since the Second World War, there has been a dramatic growth in ownership and use of private cars. Furthermore, in 1946, the Commonwealth Government-owned airline, TAA, commenced operation.

Recent changes have further reduced and fragmented the rail staff community. For example, driver-only suburban trains commenced running in 1993, with the last suburban train crewed by a guard running in November 1995. This contentious decision continues to be debated, many feeling that the guard’s role in ensuring safe travel was important. The end of paper-based ticketing saw further job losses, with loss of ticketing staff and staff supervising ticket barriers. As with all industries, change is ever-present. Even train drivers could see fundamental changes to their careers as autonomous technologies proliferate.

Driver and fireman on an A2 class steam locomotive at Spencer Street Station, c.1950

Reproduced courtesy Public Record Office Victoria

The steam locomotive driver and fireman were members of the Rolling Stock Branch. The driver was a particularly high-profile member and had spent many years working his way up, starting as a young apprentice or ‘washer’ in the workshops. Every young boy wanted to be a train driver!

The fireman managed the output of steam, a crucial position. The boiler, stoked with wood or coal, had to respond to changes in power needs as the train climbed hills, changed speed, and stopped at stations.

From the 1950s diesel trains replaced steam and the fireman lost his job, along with others — the ‘engine cleaner’, who washed the sooty locomotives, ‘the ‘pumpers’, who ensured the water tanks were filled, and the ‘call boy’, the youngest employee, who woke the sleeping locomotive drivers to start their shift.

One day while waiting for his train to arrive, one of the local drivers told me of his early years in the Rolling Stock Branch as a caller-up. It was a time when household telephones were uncommon and wind-up alarm clocks unreliable or easily ignored. Large loco depots employed a lad between 14 and 18 years of age as a caller-up, and part of his job was to make sure the early morning loco crews were woken for duty.

For practical reasons, nearly all train crews lived within a bicycle ride of the station, so about 45 minutes before a driver was due at work, the caller-up would pedal his bicycle to the engineman's home and knock on the bedroom window until he received an acknowledgement. The driver was expected to give the lad the numbered copper disc that he had collected before leaving work the previous day, as evidence that he had been woken. More often than not, all the lad heard was an ill-tempered voice telling him the disc was on a nail beside the window.

He often had a number of drivers to call and to check later they had reported on time. If a driver did not arrive at work when rostered, the caller-up would return to the house and not leave until he had the driver's signature acknowledging that a second call had been made. The extra visit incurred the displeasure of the depot foreman and the driver received a good ticking-off when he did arrive.

Thomas E. Yates, What a Journey: Life in the Victorian Railways 1948-1987, 2004

Interior of a S Class steam locomotive cabin. The driver is seated at the regulator and the fireman is shovelling coal into the firebox. It must have been heavy, hot work.

Reproduced courtesy Public Record Office Victoria

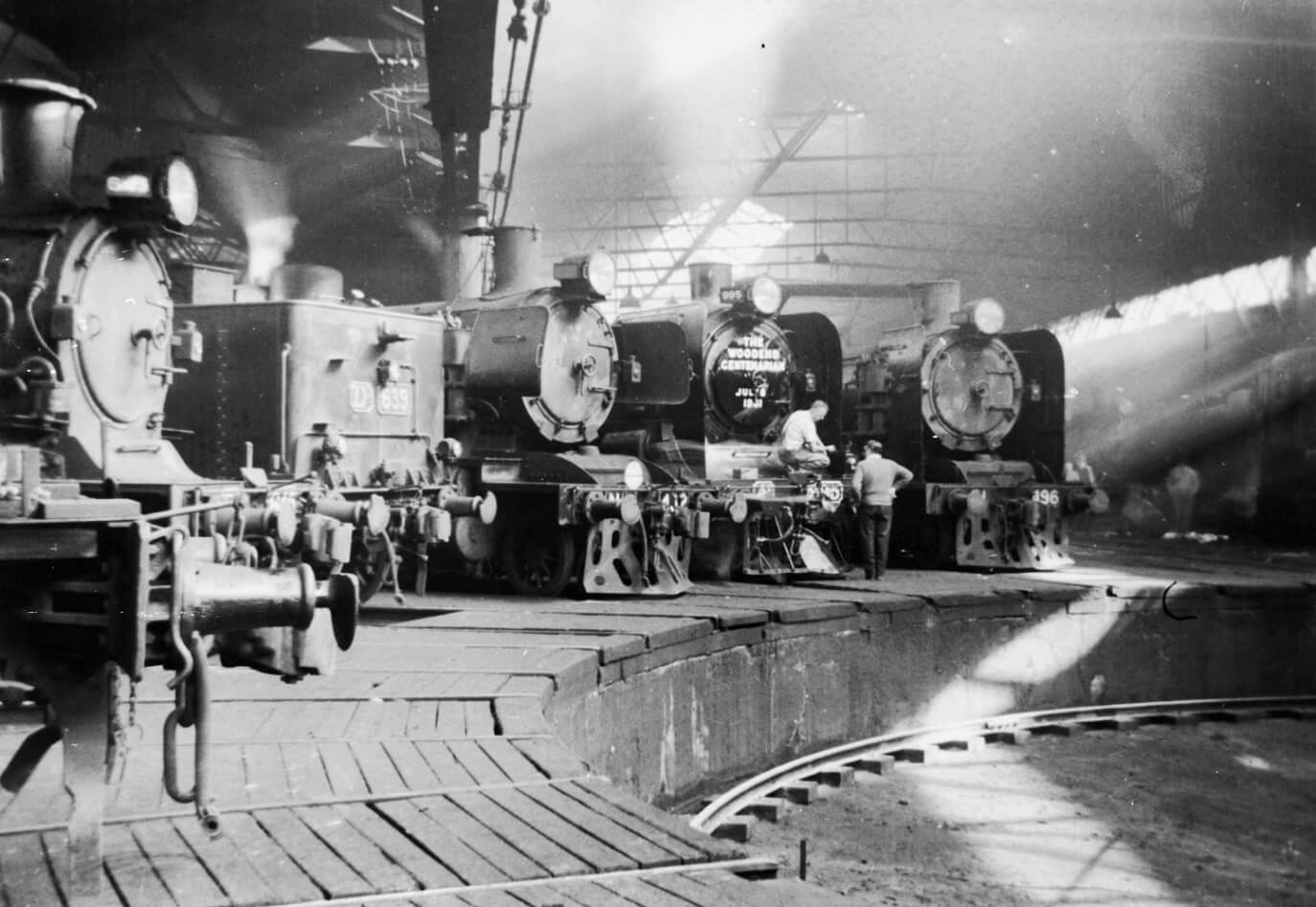

North Melbourne Locomotive Depot. Shows turntable with D Class Steam Loco No. 639, N Class Steam Loco Nos. 412 & 496, A2 Class Steam Loco No. 995 (Woodend Centenary Locomotive), D3 Class Steam Loco No. 645, July 1931

Reproduced courtesy Public Record Office Victoria

When an engine comes back to town after making a trip to the country, it is given board and lodging at North Melbourne in the State’s largest Locomotive Depot. This boarding-house for engines caters for 191 permanent lodgers, and a number of casuals. Service is high-grade. Over 450 Artisans, Technicians and Cleaners are engaged solely in looking after the guests, and there are 250 Drivers and 250 Firemen as well. The working lives of nearly 1,000 railwaymen, therefore, are centred around the North Melbourne Locomotive Depot – and its star boarders. Everything associated with locomotive running is attended to at the Loco Depot: washing out, oiling, watering and cleaning of engines, and the provision of train crews.

‘Behind the Railway scene’, publicity brochure published by Victorian Railways, 1950

Driver of an A2 Class Steam locomotive

Reproduced courtesy Public Record Office Victoria

Driver oiling an A2 Class Steam Locomotive

Reproduced courtesy Public Record Office Victoria

As soon as they come on duty… The Driver makes a painstaking examination, tests the brakes, oils movable parts, and satisfies himself that his charge is in perfect running order. The Fireman makes sure the fire is burning properly, that the level of water is correct, and that all his equipment is sound.

‘Behind the Railway scene’, publicity brochure published by Victorian Railways, 1950