Sailing vessels dominated Victoria’s maritime industry until the late-nineteenth century. John Batman and John Pascoe Fawkner sailed into Port Phillip from Van Diemen’s Land (later Tasmania) in 1835, and for many years after that most people travelled around Victoria by ship around the coast. Journeys inland were slow and arduous until the gold rush forged better roads. Meanwhile all foodstuffs and other goods had to be imported by ship from either New South Wales, Van Diemen’s Land or Great Britain.

Founding of Melbourne, Landing from the Yarra Basin, August 29th 1835. Engraving from original watercolour. Artist unknown. C. 1885

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

The journey by sailing ship from Britain was long and dangerous. Before the Suez Canal was dug in the 1860s, sailing vessels leaving England had to travel to Australia around the Cape of Good Hope, a journey that could take up to four months. Sailing conditions in the Southern Ocean were dangerous, with the risk of running into icebergs if a ship strayed too far south. But ships could encounter gales and high seas at any point in the voyage and some of the most dangerous sailing conditions were sometimes encountered in the Atlantic Ocean not far from the coast of Britain.

The crew

Sailing ships required many ‘hands’ to maintain them and keep them on course. In addition to seafarers (mostly called sailors or mariners in the nineteenth century), who were expected to manage the sails and steer the ship, the crew of a large seagoing vessel normally included officers, a ship’s carpenter and a sailmaker. There might also be a cooper, to make or repair barrels. Drinking water and food rations were stored onboard in barrels. Large vessels carrying passengers often employed a doctor and/or a surgeon for the inevitable emergencies on long sea voyages. Children also found employment on ships, as cabin boys and junior sailors.

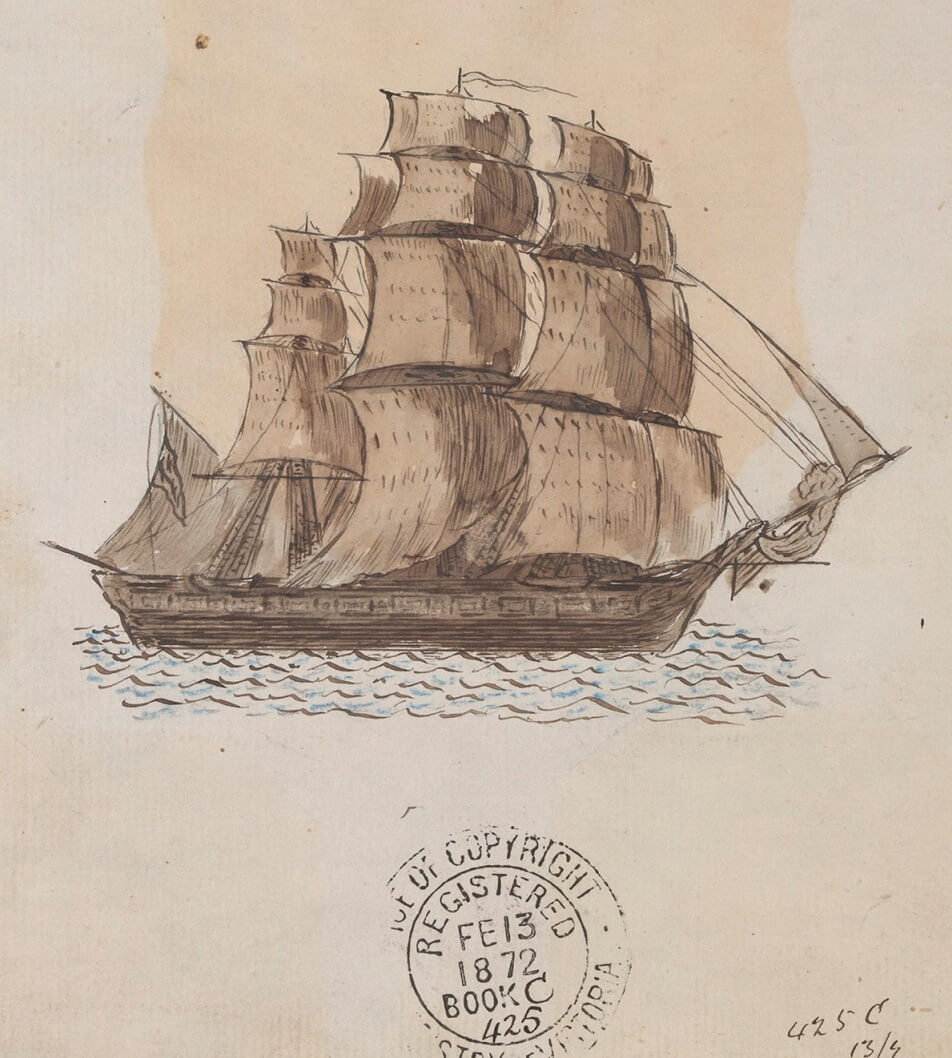

Full-rigged sailing ship under sail, William Watson artist, 1872. Pen & ink drawing

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

Associated trades

Many other trades were associated with sailing vessels. They included sailmakers, riggers, ropemakers, ship chandlers (who supplied vessels with their many requirements), shipwrights (who built or repaired ships), block and mast makers. And then there were the specialist instrument makers, who made the sextants, compasses and chronometers essential to navigation.

Thomas Keane, Ships Chandler, Gawler Street, Portland, c. 1880.

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

The interior of Andrew Heriot’s sail loft, Nelson Place Williamstown, 1885

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

This sail making shop appears to employ both experienced sail makers and boy apprentices.

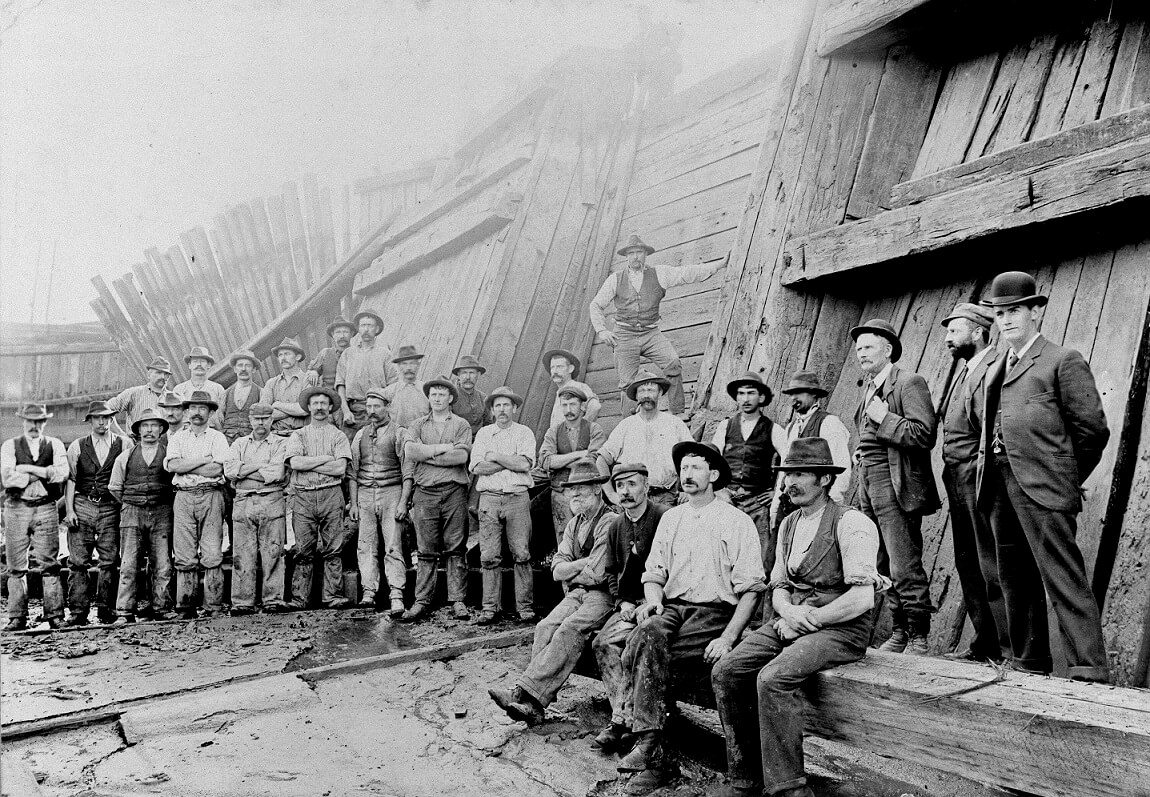

Workers at the Duke and Orr’s Amalgamated Dry Docks, c.1900

Reproduced courtesy University of Melbourne Archives

Dry docks were large structures used to build, repair and maintain vessels. They were built adjacent to ports with water access. Ships sailed into the dry dock, after which water was pumped out of the dock to expose the ship’s hull. Shipwrights (ships’ carpenters), metal workers and other tradesmen were employed in the dry docks. Work had to proceed promptly, especially on wooden-hulled vessels, to prevent the timbers drying out. Once work was completed, water was let into the dock through valves to refloat the ship. Above workers pose at the Duke and Orr’s Amalgamated Dry Docks, which were built in 1875. Most of the workers wear soft felt hats, though some wear caps. The overseers wear suits, but one man, perhaps one of the owners, has a (more expensive) bowler hat and sports a pocket watch. The old dock is listed on the State Heritage Register and now houses the historic barque Polly Woodside.