The first steam-powered ships arrived in Victoria in the 1850s. The SS Great Britain was the first to arrive under its own power in 1852, but smaller craft may well have arrived earlier on board sailing ships, for use on the river. Like most early steam ships, the SS Great Britain also carried sail, in case the engines failed at sea and to increase speed. It was the first steam ship to be powered by a propeller, designed by engineer Isambard Brunel. It carried 15,000 passengers to Australia over the next 20 years, including the first English cricket team to tour Australia (in 1861) and author Anthony Trollope (in 1871). In time steam engines replaced sailing ships, but the transition was a long one, extending over the next 50 years. Until into the twentieth century sailing ships moored alongside steam ships at wharves in Victoria.

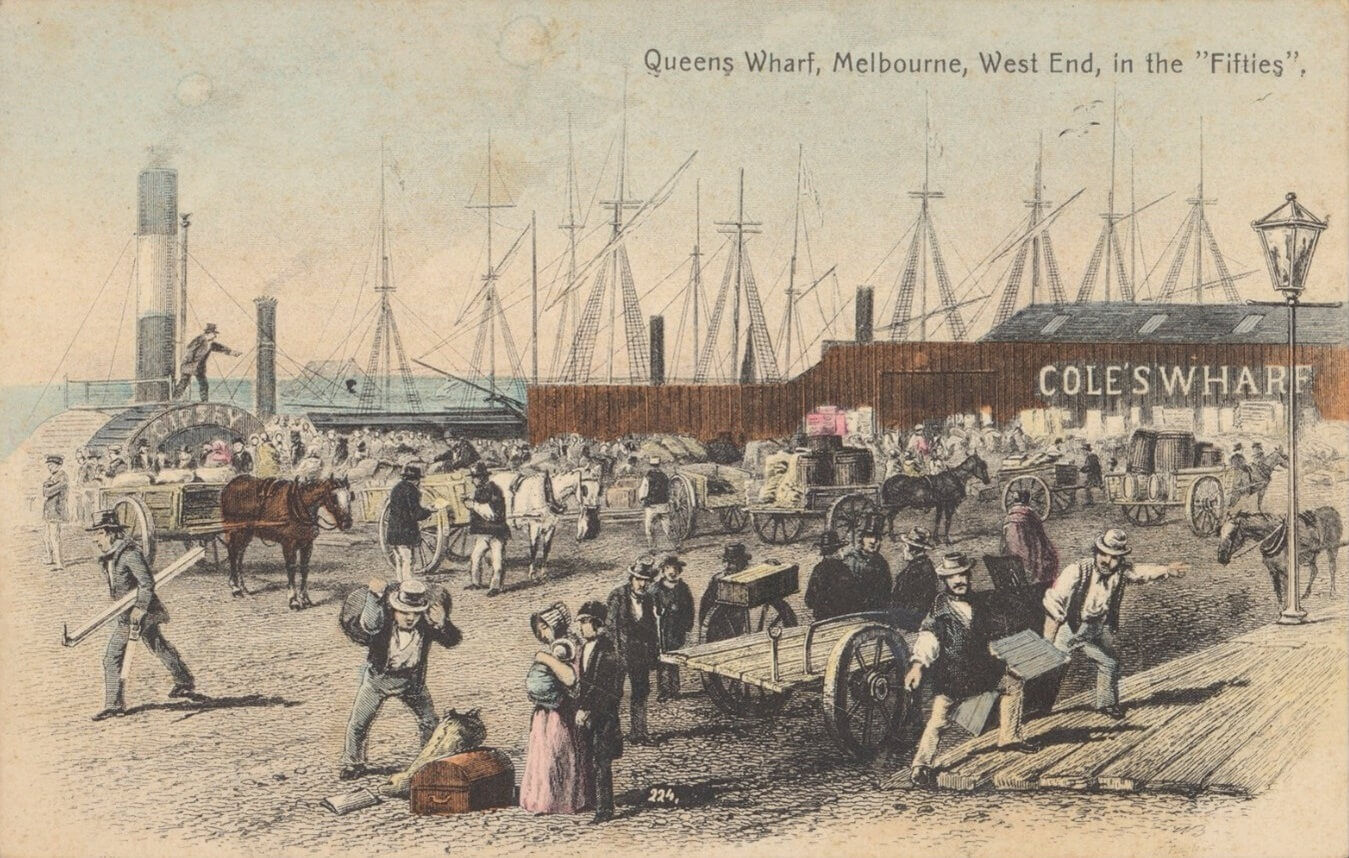

S T Gill Queen’s Wharf, Melbourne, West End, in the “Fifties”

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

During the gold rushes, Melburnians often observed a ‘sea of masts’ from ships anchored in the harbour. In this busy 1850s wharf scene artist S T Gill drew both travelers, carrying trunks and bundles, and workers transporting cargo (both crates and barrels), while in the background an overseer supervises unloading. The overseer appears to be standing on the paddle wheel of a steamship and two funnels from steamships are painted behind the wharf. Paddle wheelers were very effective in harbours and rivers but performed poorly on the open sea, as waves rocking the ship lifted the paddles out of the water. As this scene indicates, a small army of workers serviced ships tied up at the wharves. They included not only those who worked on the wharf, loading and unloading, but also the many carters who transported goods from the wharves to businesses in the city. In the image above Queen’s Wharf is still called Cole’s Wharf, its original name.

Cole’s Wharf

Cole’s Wharf was a privately-owned and operated wharf built by entrepreneur (Captain) George Ward Cole in 1841. Cole’s career began as a mid-shipman in the British navy during the Napoleonic Wars. He saw action in Santo Domingo and then in the United Sates, and eventually qualified for appointment as a Lieutenant and then as a First Lieutenant. At the end of the war, in common with many others, he was placed on half-pay and appointed to the rank of Commander but chose to go into the merchant navy. As Captain or Commander he sailed on various trading voyages, some perhaps on his own account. At one time he was based in Sydney. In 1840, at the age of 47, he arrived in Melbourne with his son and two stepsons (the wife of his short-lived marriage had died,) and decided to stay.

Cole was an energetic man, with a clear eye to the future. He saw immediately that Melbourne’s elementary port facilities were a hindrance to development and set about negotiating permission to develop a private wharf. Estimates of the cost of this enterprise vary between £60,000 and £80,000, but regardless, it was an enormous sum. Cole must have been a very wealthy man, although the source of his wealth is obscure. At the same time he set about finding a wife and in 1842 married Thomasina Anne McCrae, apparently against the wishes of some members of her family. He built several houses, including a large house, St Ninian’s, in Brighton and in 1859 commissioned a fine pair of portraits of himself and his wife from the artist John Irwin.

John Irvine, Mr G.W. Cole c. 1859

Reproduced courtesy Bayside City Council Art and Heritage Collection

John Irvine, Mrs G.W. Cole c. 1859

Reproduced courtesy Bayside City Council Art and Heritage Collection

Cole survived the economic downturn of the 1840s in Melbourne, although he came near to bankruptcy, and developed diverse business interests around his wharf. However after

Separation in 1851, government cast increasingly-envious eyes on the profits to be made from wharfage fees, and passed successive pieces of legislation to claim those profits. Cole eventually sold his wharf to the government in 1868 for a fraction of its cost, but only after many years of wrangling and legal argument.

Although disappointed in his plans for the wharf, Cole pursued many other interests. As a strong advocate of the benefits of steam, he became director of the Port Phillip Steam Navigation Company and in 1851 built the first screw propeller steamer to be commissioned in the Southern Hemisphere. The City of Melbourne provided the first regular steam ferry service across Bass Strait. His business interests were diverse and included many investments in property. Although he was never able to implement such schemes himself, he proposed many improvements to the river and the harbour, including several flood mitigation measures that were very similar to the proposals eventually advocated by Sir John Coode. From 1853-55 and then 1859-79 he served as a member of the Legislative Council. Cole was apparently a fair employer, earning praise in 1860 from the Age newspaper for his ‘liberal’ views and his support for working people.

Captain Cole appears to be one of the few wealthy men, desirous of a seat in Parliament, who have large liberal just views as to what is due to the welfare of the people, and as to what is the best and soundest policy for new countries such as ours. He comprehends the wisdom of being liberal to the working classes, in allotting them their share of the natural advantages held out by a new country. He is a lucky exception to his class; and we are pleased to see him again seated in the Legislature. (Age, 21 September 1860)

Praise indeed from this newspaper, which could be scathing in its opinions, especially of members of the Legislative Council. On Cole’s death in 1879 no less a humanitarian than Chief Justice George Higginbotham provided this obituary:

He was always thinking of the public welfare, and was never wearied in advocating measures which he thought calculated to promote it... No politician in recent Australian history appears to present a record of purer and more sincere patriotism, or of more unselfish and benevolent political action than Captain George Ward Cole. (George Higginbotham, quoted in Isaac Selby, The Old Pioneers' Memorial History of Melbourne, 1924, p.248.)

Cole left an estate valued at £17,950 to his wife, son and daughters. (Probate on the will of George Ward Cole 28 May 1879, Supreme Court of Victoria, Public Record Office Victoria, VPRS 7591/P2, item 19/131)

Ferries and paddle steamers ran regular services between Melbourne, Geelong and Williamstown, while smaller steamers ferried pleasure-seekers to the Cremorne Gardens in Richmond and to other scenic spots, including Dights Falls and the Botanic Gardens. Other ferries cruised the Yarra, some with dance floors for evening patrons. The paddle steamer Gondola carried passengers from Princes Bridge to the Cremorne Gardens, where visitors were treated to stage performances and fireworks displays, in addition to the gardens themselves. In the background to the left of the picture is a smaller passenger boat, powered by two oarsmen. The passengers are shielded from the weather by a canvas awning. It would have been a hard pull for the rowers, since there seem to be six passengers!

By the time François Cogné painted this lovely watercolour in 1864, the city of Melbourne had expanded significantly around the wharf area. Impressive stone buildings lined Flinders Street and included the Customs House, one of the first stone buildings erected in the colony. In the foreground several rowing boats are shown ferrying passengers across the river, while two wooden-hulled ships are anchored at the wharf. The steamship carries substantial masts because sail was used as auxiliary power to save on coal on long voyages. Sail was also used to increase the ship’s speed. Sail and steam could be used at the same time. Sail was also a back-up in case the steam engines failed at sea. Cargo has been unloaded onto the dock from the smaller, two-masted schooner and includes the ever-present assortment of casks and barrels. Today, the capacity of ships is still measured in tons, a reference to the number of tuns or casks a vessel could carry.

‘Railway Pier Sandridge’, by Charles Nettleton, photographer, c.1885

Reproduced courtesy Public Record Office Victoria

Sailing ships and steamers were anchored side by side at the busy pier at Sandridge (Port Melbourne) when this photograph was taken by Charles Nettleton in 1885. Sail and steam were complementary technologies and as late as 1885 Melbourne’s docks were still crowded with masts. Many wharf labourers posed for this photograph, alongside cargo in crates, bales and barrels. A steam engine in the foreground hauls several wagons loaded with cargo. The first trains were used to service shipping, carrying cargoes from the country to the docks.

Railway Pier Port Melbourne, 1879

Watercolour, Julian Rossi Ashton artist

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

Both sailing vessels and steam-powered ships are berthed at Railway Pier in this romantic watercolour painted in 1879 by Julian Rossi Ashton.

Railway Pier Port Melbourne, c. 1912

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

By 1912 the sailing vessels have largely given way to steamers, as shown in this postcard of Railway Pier.

Queen’s Wharf, probably just pre-World War I

VPRS 8362/P1, unit 5, item 431

Reproduced courtesy Public Record Office Victoria

This photograph was dated 1940 in the Public Record Office catalogue, but we think it is much earlier than this. It is certainly post-1883, when the ‘Falls’ were removed from the Yarra, and almost certainly pre-1940, when the last cable tram ran from Bourke Street. The number of horses and carts and the small number of motor cars suggests pre-1920s, as does the clothing of the only woman visible in the photograph. The conversion of the cable trams to electricity began in 1916, but there is no sign of the wires here, so a date pre-1916 may be indicated.. Are there other clues we have missed? The State Library Victoria has a similar image which they have dated 1911.