A child’s life

Goldfields must have been exciting places for children, but also unsettling and dangerous. Families moved about a lot. They often lived in makeshift shelters and there were hazards everywhere. Open fires, unprotected mineshafts and fast-flowing water courses all took their toll. But the greatest threat to children, especially young children, was disease. Whooping cough, measles, diphtheria, and scarlet fever spread quickly in the crowded, unsanitary conditions. In the 1850s one quarter of all the recorded deaths in Ballarat involved children under five.

A sobering record

Dysentery, a type of gastroenteritis causing vomiting and diarrhoea, was the great killer, particularly during the summer months when the streams ran dry and water was scarce and polluted. In March 1852 the Argus reported, ‘Dysentery...[is] now stalking abroad through the Diggings... Death follows death in quick succession, until the humble little burial place of four graves, to which one of your correspondents has alluded, has gradually assumed the appearance of a town cemetery.’

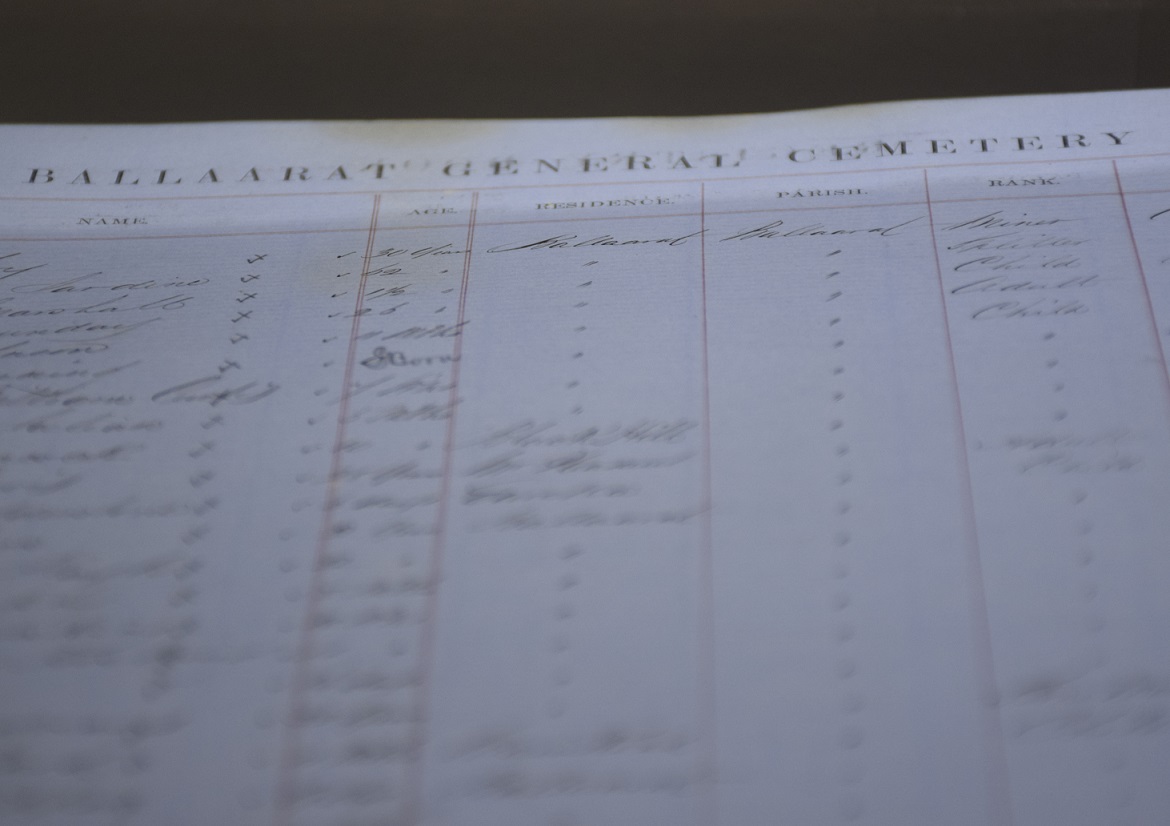

The record book from the Ballarat Cemetery is a sobering reminder of infant mortality. Of the 40 entries on one page, for example (February 1857), 26 were children, including 17 children under 12 months who died of dysentery.

Calling the ‘doctor’

Most families on the early goldfields could not afford a doctor. In 1854 four-month-old Jean Edoes Carey died of a fever. When the coroner asked Patrick Carey why he had not sent for a doctor, he replied: ‘Because we had not a blessed sixpence in the tent’. Click here to read the Coronial inquest into the death of Jean Edoes Carey (6mb). Reproduced courtesy Public Record Office Victoria.

In any case doctors at this time could do little to fight a child’s raging fever, or treat diarrhoea. A popular remedy for dysentery was chalk, opium and brandy – but these were expensive ingredients and hardly suitable for a child.

Doctors on the goldfields also had a dubious reputation. ‘It is no joke to get ill at the diggings; doctors make you pay for it’, wrote Ellen Clacy in 1855, ‘many are regular quacks, and these seem to flourish best.’

Here artist Samuel Thomas Gill depicts a family at work. While the man pours water into the cradle, the woman rocks it back and forth, while nursing a baby. Behind her a boy is also at work, shovelling dirt. We know that children worked on the goldfields, sometimes alongside their parents, sometimes in teams with other men. The work was hard for children and could be very dangerous.

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria.

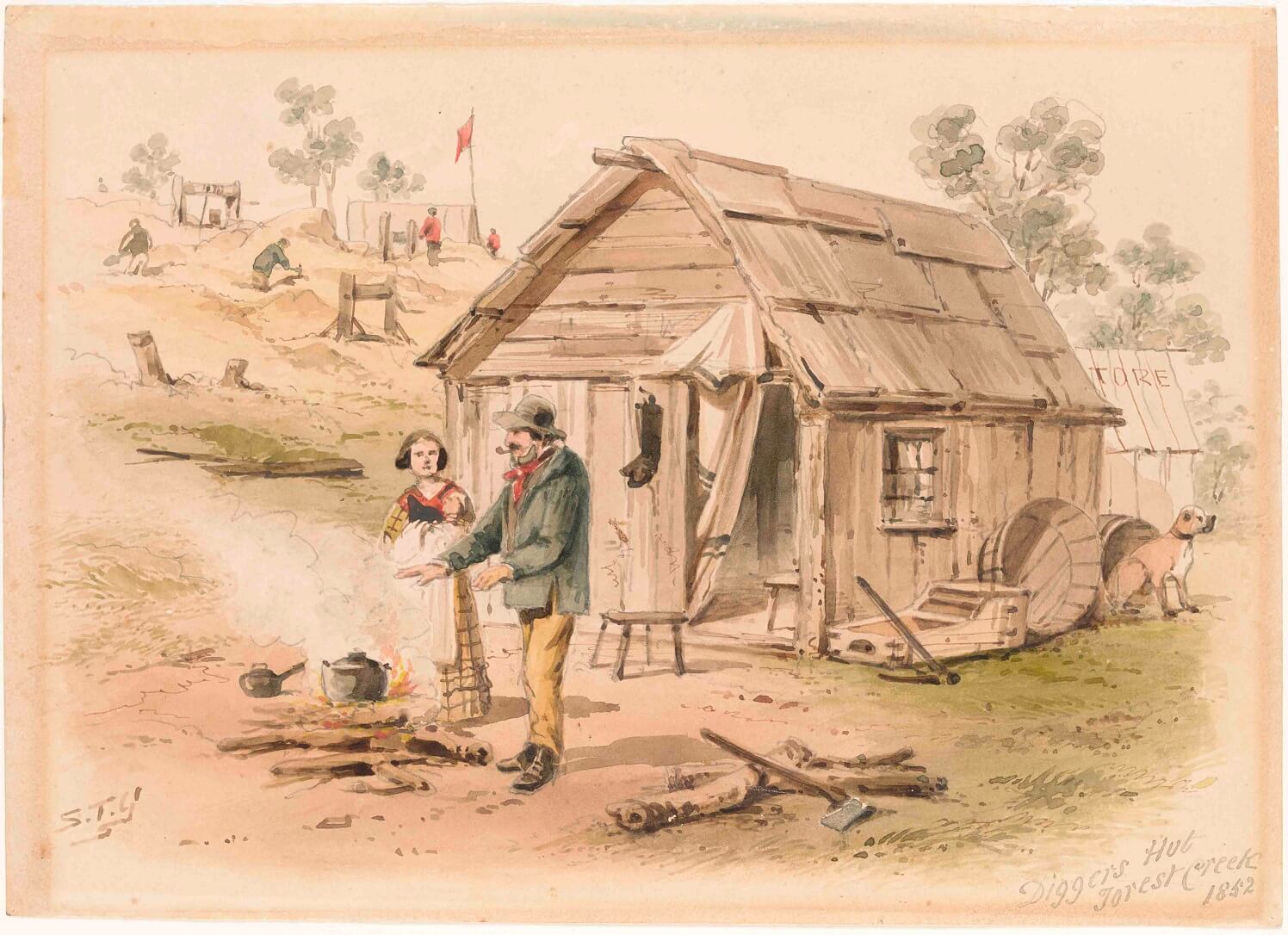

This digger’s hut is rough, but probably much better than most shelters on the diggings. Conditions were very hard for women, cooking over open fires and with no other facilities. Managing babies on the diggings must have been especially difficult – and dangerous!

Watercolour by Samuel Thomas Gill, 1872. Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria.

Author: Ann Wilcox