They say a person is defined by their chamber pot. Well probably not, but it is easy to imagine that this would be just the style that Mayor Smith or his wife Ellen would have fancied for themselves. Athena in her chariot fueling the Smiths sense of themselves and their position in newly forming Melbourne society.

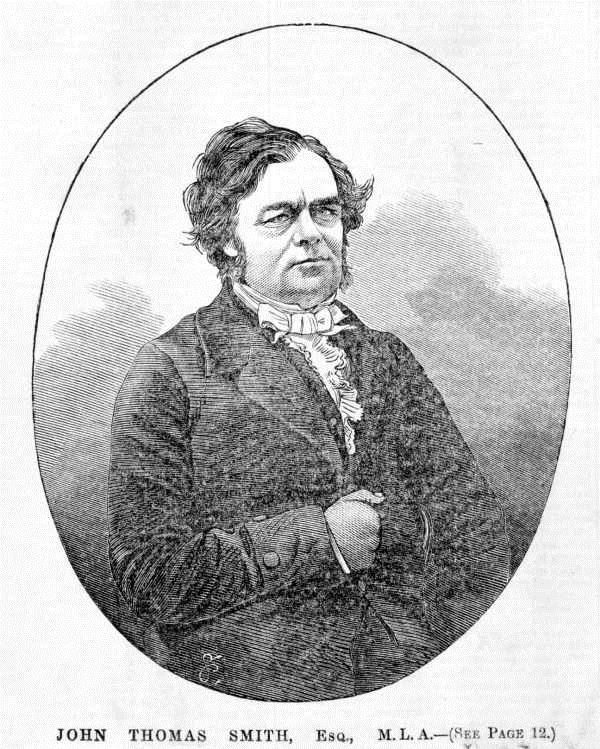

John Thomas Smith, 1863. Creator: Samuel Calvert; Source: State Library of Victoria.

The chamber pot was discarded by the Smiths in a disused cesspit at their Georgian manor on Queen Street, Melbourne. At a time when toilets were outdoors, people kept a chamber pot in their bedroom to tend to their overnight toileting needs. For those lucky enough to have a servant, the job of emptying it could be outsourced.

A Rapid Rise

John Thomas Smith had made the dazzling rise to Mayor of Melbourne in 1851, the very year that gold was found by Europeans in Victoria. This is quite an astonishing case of rapid social mobility in the gold rush era as Smith was the Sydney born son of a convict shoemaker. His mother was also born in Sydney to convict parents. Smith arrived in Melbourne in 1837 and in 1839 married Ellen Pender, an Irish Catholic free settler who came via Tasmania. She was the daughter of a publican and Smith was encouraged into the business by his father-in-law. The Smiths started amassing significant wealth running pubs and the Queen’s Theatre.

Gold rush Melbourne was a place of rapid change and rapid social mobility. The gold rush brought great opportunity to European settlers already in the colony prior to 1851, even if they never went to the gold fields. The growing city needed men like Smith: there was a lack of people with the requisite pedigree and the doors were wide open for him. It was essential to Melbourne’s governance and success that men such as Smith were accepted into positions of power.

Fancy Rubbish

In the 1860s the Smiths built a new stable in the area where their cesspit had been. They filled it with household rubbish before erecting the stables. This cesspit was excavated by archaeologists in the 1980s and the collection was subsequently stored at Museums Victoria. A recent research project has catalogued and analysed the contents of the cesspit.

This chamber pot found in the cesspit harks back to the grand, classical traditions of the old country but is not as grand as it seems. The transfer print is poorly applied and there are glaring gaps. It was, it seems, purchased from the seconds’ market. A flawed object sold at a cheaper price and a purchasing strategy that helped to determine and display the Smiths position in this new, flourishing gold rush city.

Much of the tableware chosen by the Smiths was colourful and elaborate, but also flawed.

Transfer-printed and hand-painted plate from the Smith’s cesspit. Note the patchy glaze and other flaws. Object is part of Museums Victoria’s collection. (Source: S. Hayes).

This was a family enjoying their wealth. In Gold Rush Melbourne, possessions (rather than background) became an important measure of status.

Read more about the Smith family and the archaeology of 300 Queen Street in this article and new book by Sarah Hayes.

Author: Sarah Hayes, Historian