[A]dvise him first to go and dig a coal-pit; then work a month at a stone-quarry; next sink a well in the wettest place he can find, of at least fifty feet deep; and finally, clear out a space of sixteen feet square of a bog twenty feet deep; and if, after that he still has a fancy for the gold-fields, let him come…

- Author and miner, William Howitt

A gold digger must be a Jack-o-all-trades; he must be able to strip bark, fell a tree, and saw it, dig sods, make embankments, put up a hut, mend your clothes, draw firewood after chopping it, bake, boil, and roast, use a pick and spade, delve, dig, and quarry, load, and unload, draw a sledge, and drive a barrow, cut paths, make roadways, puddle in mud, and splash ankle deep in water, with occasional slushings from head to foot, bear sleet and rain without flinching during the day, and sleep in damp blankets during the night, thankful that they are not entirely saturated – if you can do all this, and have spirit enough to attempt it, and endurance enough to carry it on for three months, why there is gold and rheumatism in store for you.

- Alfred Clarke, The Geelong Advertiser, 19 September 1851

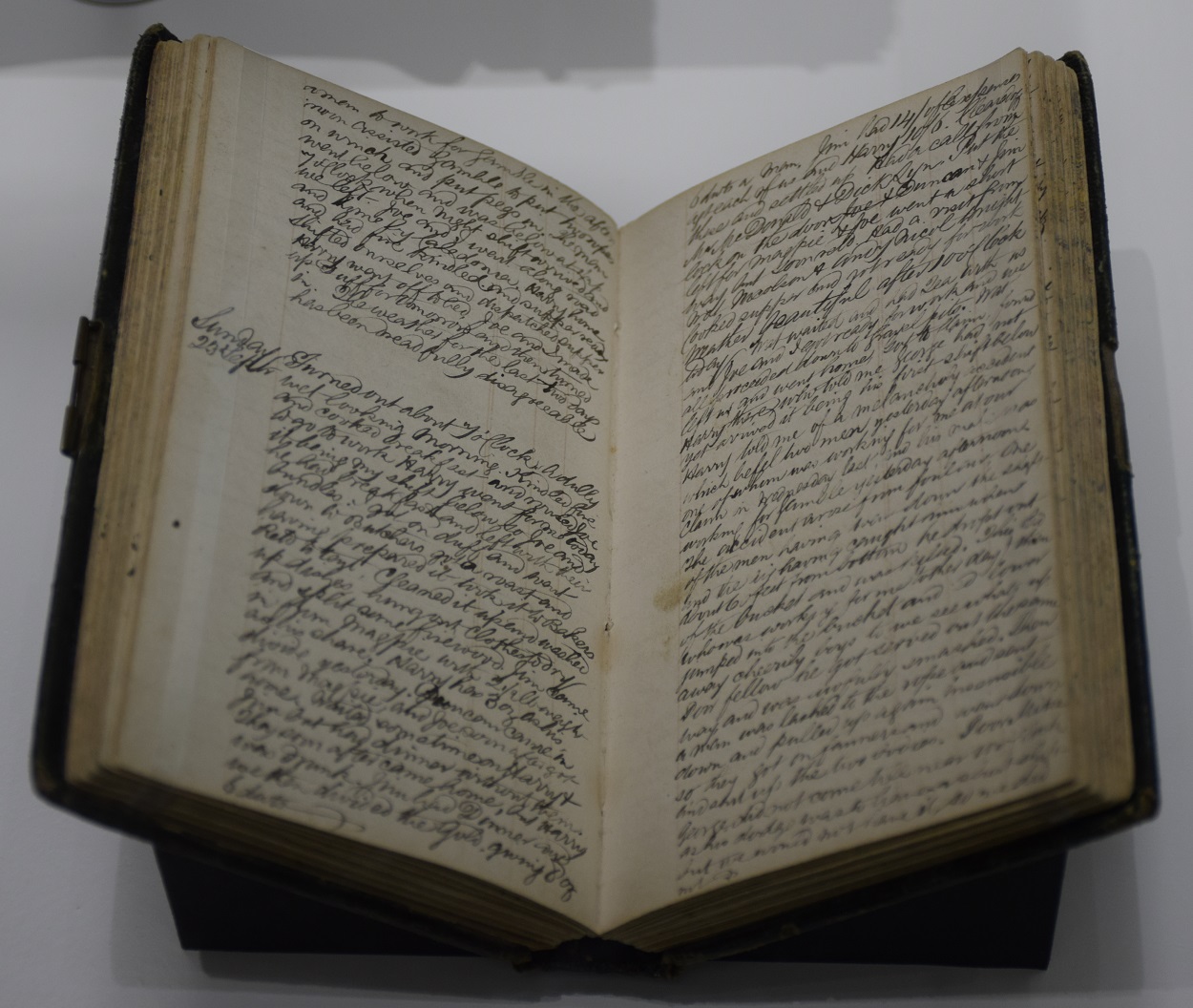

Object 8 in the exhibition is a 223-page diary written by a Scottish gold-digger on the Ballarat goldfields. The diary is on loan from State Library Victoria.

The diary was written over a six-month period, from 8 July 1855 to 1 January 1856. It is closely written in black ink in a ruled cash book bound in black leather. The author’s name remains a mystery, but his handwriting, spelling, grammar and talent for description suggests a good education.

The diary includes the account of a fire that killed 11 people, the murder of a butcher, theatrical performances by Lola Montez, Charles Thatcher and others, the arrival of new prostitutes in town, even the escape of a Bengal tiger from the Montezuma Circus into Ballarat's Main Street. But it is the author’s description of daily life on the goldfields that makes this diary so interesting!

Daily life

The diary contains descriptions of daily chores, meals and weather conditions.

It opens with the following typical entry:

Got up about 9 o’clock. Had breakfast and accompanied John Adams, Dugie Weir, Jim Young & Bill Douglas out to Magpie Gully to assist in erecting their log hut. Engaged all day in getting up the logs and building chimney. Returned after sunset pretty tired and hungry.

One of the lucky ones

The first rush to Ballarat was in 1851 when nuggets of gold could be found in the shallow surface soil and the lucky ones could make small fortunes easily and overnight. This miner arrived in time for the second rush, when miners had to work in incredibly trying conditions, sinking deep shafts and tracing the underground leads.

Some found great nuggets on the Ballarat field. Others, like the miner, discovered some gold, enough to pay his way: ‘Took home our tools and on getting home, dried gold and cleaned it & weighed it out. ‘This is the last of the Tucker Hole and a good hole it has been.’

‘Such work… will finish me, but there is no help. I shan’t give in.’

Mining was hard, hazardous, dirty work, with no certain return at the end of it. This miner worked in shifts, day and night, in deep shafts up to 40-feet deep. He was often waist-deep in water: ‘Got to work and went down and sunk until about one o’clock. Shaft dreadfully wet. It fairly spouted mud and water out of the drifts above. Before I was 5 minutes down I got such a soaking as I would have on being plunged into a creek.’

Labouring in the cold, dark, wet earth took its toll: ‘Feel very stiff & sore after my drenching. Hands and arms fearfully cut up, cracked and smashed. Such work for a month will finish me, but there is no help. I shan’t give in.’

Tent living

Life on the goldfields was exciting but conditions were harsh. The miner lived in a simple tent; canvas thrown across a timber frame, pegged to the ground over a dirt floor. For more comfort, he built a mudbrick fireplace at one end.

The tents were cold in winter, hot and stuffy in summer and unpleasant when it rained: ‘Got home and found the tent afloat and my blankets wet’. Flies and ‘troublesome fleas’ were a scourge during the summer months, as was the ‘incessant mosquitoes’.

With very few women on the goldfields, men had to perform what was traditionally female work. The miner took it in turns to cook and keep the tent, but he wasn’t particularly good at it though: ‘Kindled fire and cleaned up tent. Boiled kettle and prepared supper. Ironing my blankets, I burned one of them.’

A simple diet

The miner’s diet was very simple. It consisted mostly of mutton and duff (‘duff’ is a flour pudding boiled in a bag), with the occasional potato. Such diets, with almost no fresh fruit and vegetables, left diggers prone to all manner of ailments, including scurvy. The diet certainly accounted for the continual festering of abraded hands and knuckles, which few diggers could afford, and aggravated the incidence of the infectious diseases which were a feature of digging life.

Disease

Hygiene was an issue on most goldfields, especially in the 1850s. Streams around the diggings were soon polluted by gold washing, refuse and worse, causing widespread dysentery, then the dreaded typhoid fever. Other common inflictions were the respiratory diseases, rheumatism and cramp produced by working in water and sleeping in damp clothes or on wet ground.

The author had numerous bouts of dysentery, each time making him ‘too weak to work’. He also suffered from an ongoing bronchial complaint, ‘easily tired today cough being rather troublesome.’ His cough became so bad that his doctor advised, ‘the sooner I cut my acquaintance with the Diggings the better for me.’

A dangerous job

A digger’s life was dangerous and many died trying to make their fortune. Accidents were common. Mine shafts collapsed, killing diggers trapped under rock and timber. Shafts flooded with water while men were working in them, or filled with poisonous, deadly fumes, known as ‘foul air’.

In his diary the miner tells of a man ‘smothered today in a shallow sinking’, and recounts the death of two men working near him:

The accident arose from foul air. One of the men having went down the shaft and the air having caught him when about 60 feet from bottom he dropped out of the bucket and was killed. This lad who was working for me t'other day then jumped into the bucket and sd. lower away cheerily boys to we see what's up. Poor fellow, he got served out the same way and was awfully smashed.

In 2013 UNESCO added this goldfields diaries to the Australian memory of the world register. Founded in 2000, the UNECSO Australian memory of the world register was the first in the world; now there are more than 60 national Memory of the World programs, and is designed to list documents that have significant documentary heritage.

Click here to read the full diary online at State Library Victoria.

Author: Ann Wilcox