During the 1850s the population of Victoria almost trebled as gold seekers surged into Melbourne then onto the goldfields.

The gold licence

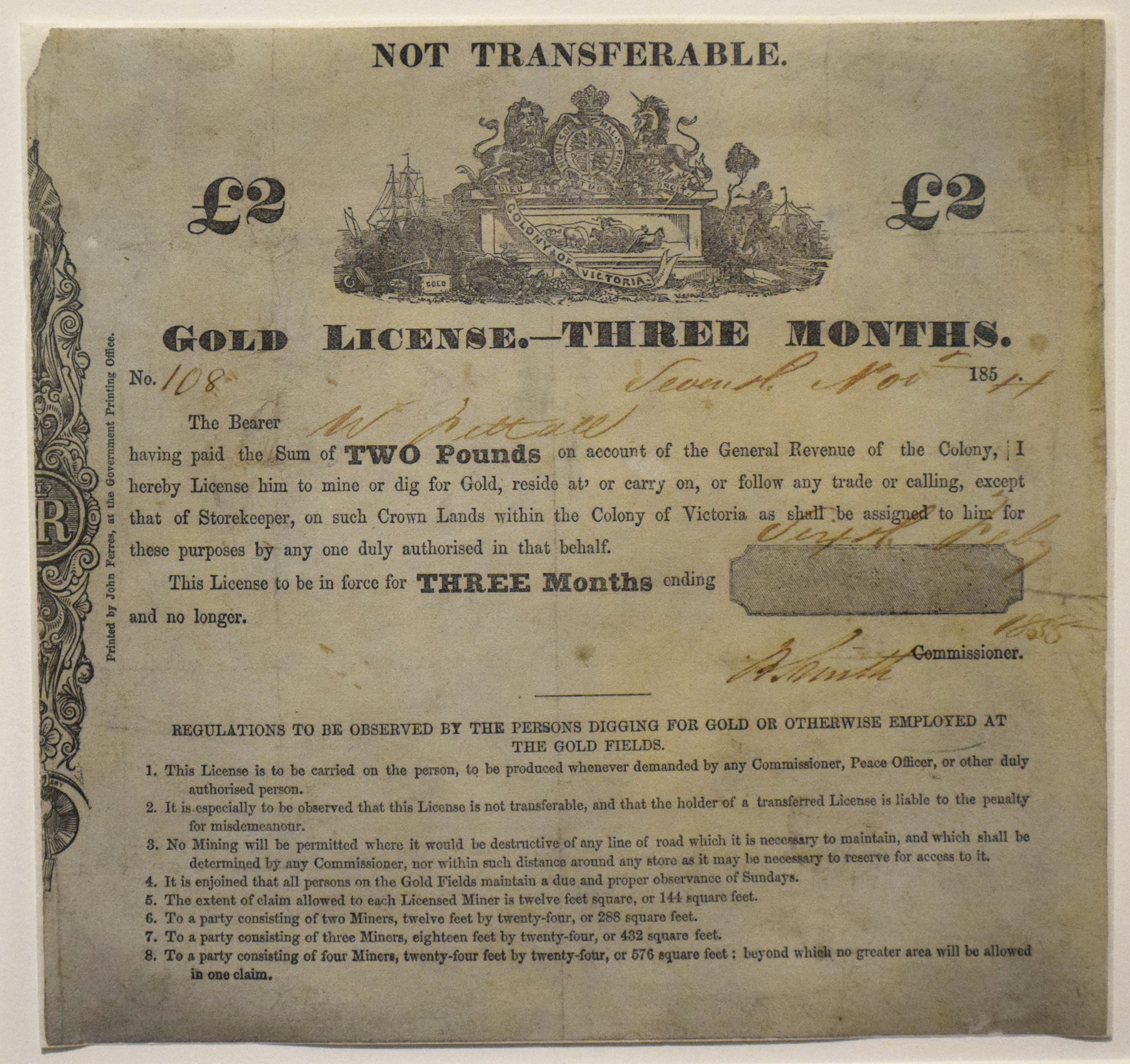

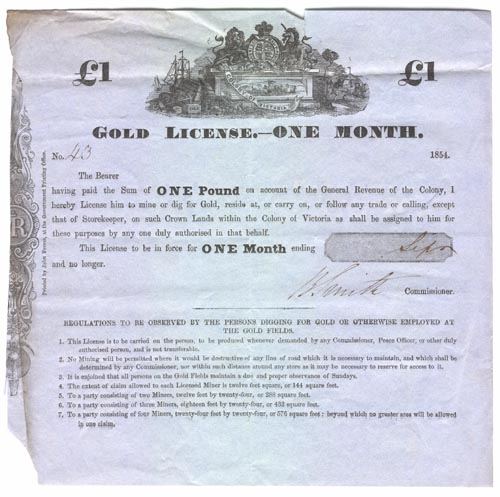

The colonial governments in Melbourne and Sydney imposed a licence fee to dig for gold. This licence gave a miner the right to peg out a small ‘claim’ of eight feet square (2.4m).

Licences helped the government keep track of the large number of people moving to the goldfields. They also raised money to pay for roads, administration and police.

An unfair tax

From the start miners complained that the licence was expensive and unfair, since they were required to pay whether they found gold or not. They also felt that it was unreasonable that miners were taxed when they were not represented in the government. (Because they did not own the land, the majority of the diggers did not have the right to vote or to stand for election to Victoria’s Legislative Council.)

Disaffection grew as the fees rose and policing methods became more punitive.

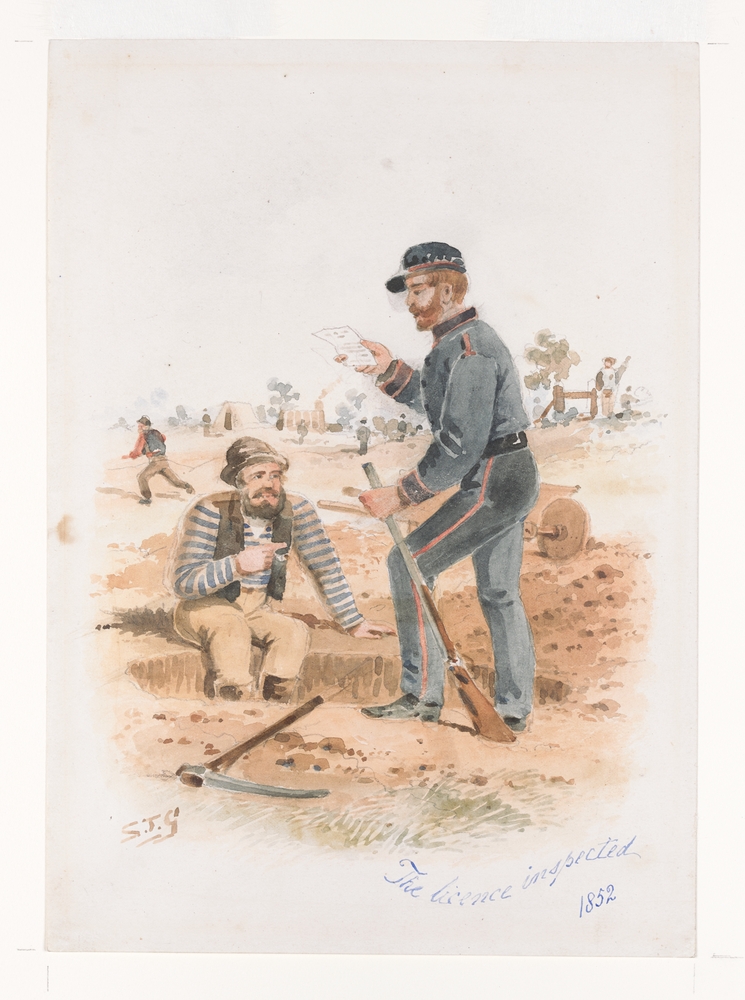

Gold commissioners, assisted by police, conducted regular ‘licence hunts’, often treating miners with cruelty and contempt. Assistant Commissioner Armstrong was said to beat diggers unconscious with the brass knob of his riding crop!

Object 5

Gold Rush: 20 Objects, 20 Stories

Object property of Gold Museum Ballarat.

<Previous Object | Next Object>

For more educational information about the Eureka Stockade, please visit the Public Record Office Victoria website.

The monthly fee of £1 for a licence imposed great financial hardship on the average miner, who might spend long periods digging for gold without any success. As opposition grew many miners refused to buy a licence. Others simply could not afford one.

This licence, dated 1854, cost £1.

Reproduced courtesy Public Record Office Victoria

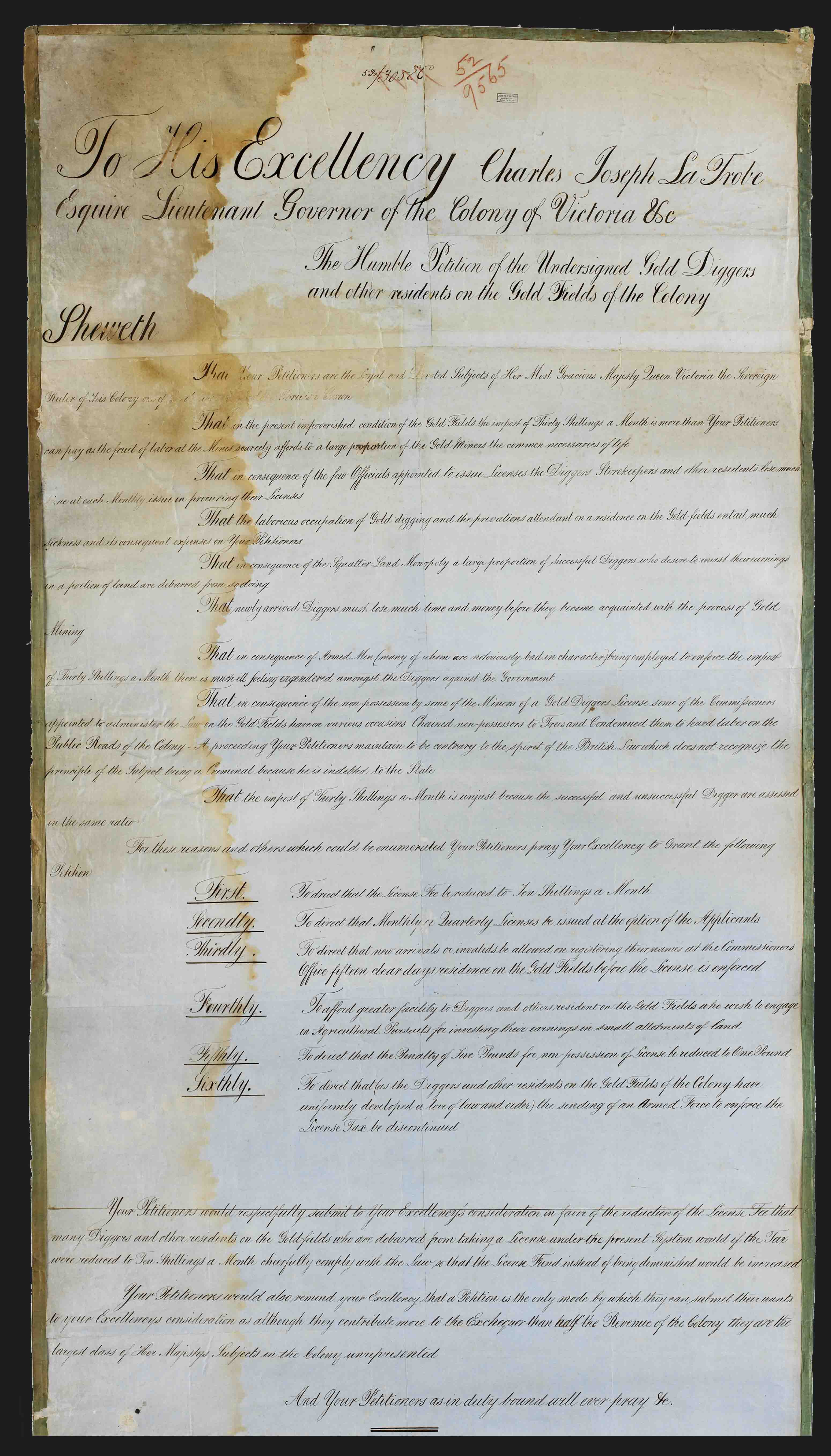

Organised resistance to the license fee spread throughout the fields, with large public meetings and demands for redress. Several petitions were collected.

This 1853 petition was signed by more than 5,000 people, including diggers at Bendigo, Ballarat, Castlemaine, McIvor (Heathcote) and Mount Alexander (Harcourt).

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

(LEFT) Watercolour by Samuel Thomas Gill, 1872. Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

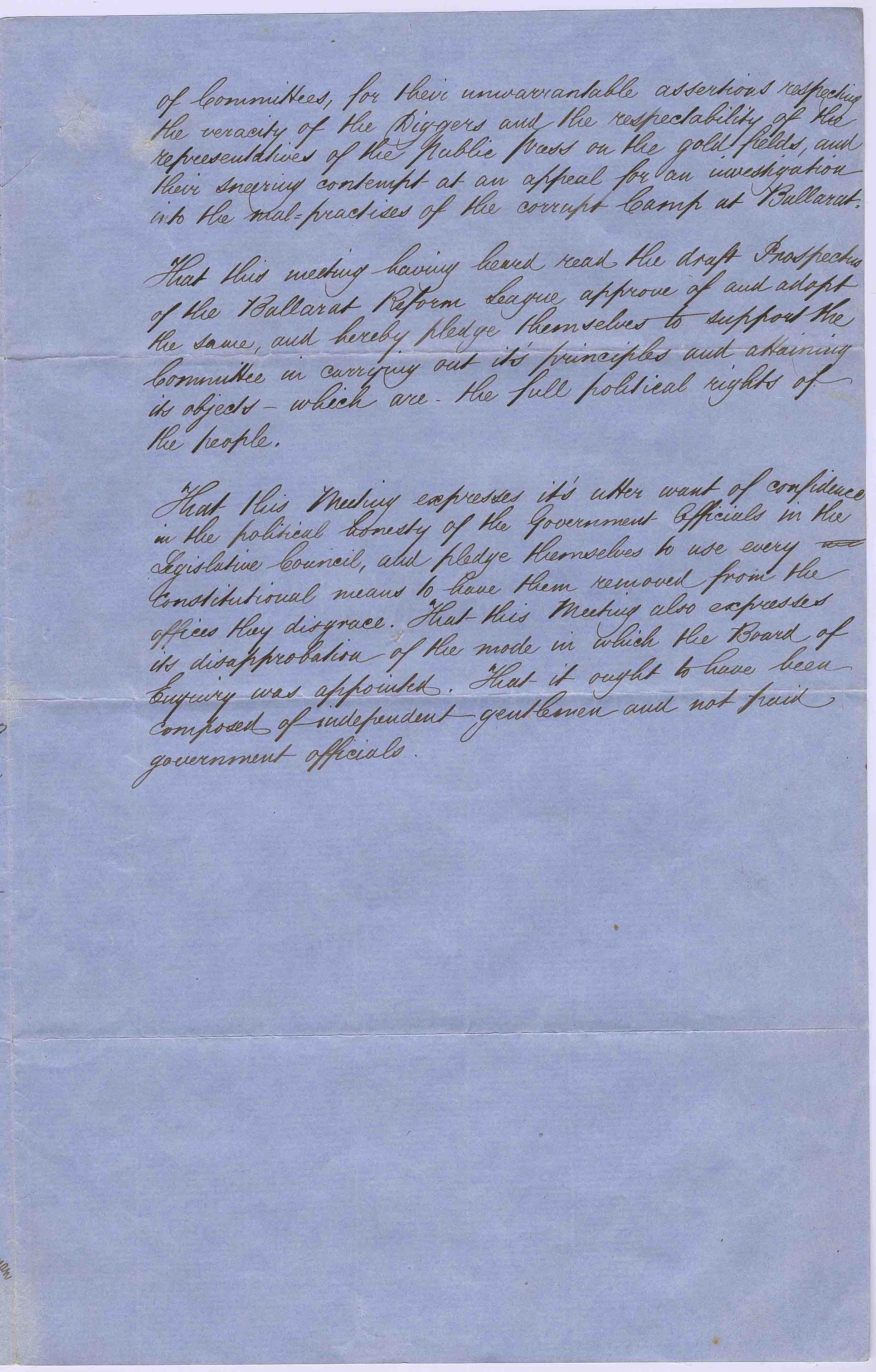

(RIGHT) Diggers licenceing [sic] Forest Creek by Samuel Thomas Gill, 1872

Watercolour reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

Licences had to be carried at all times and there was very little leniency shown by police. Even if a miner had lost his licence, or it had been destroyed in dirty or wet working conditions, he could be fined or gaoled.

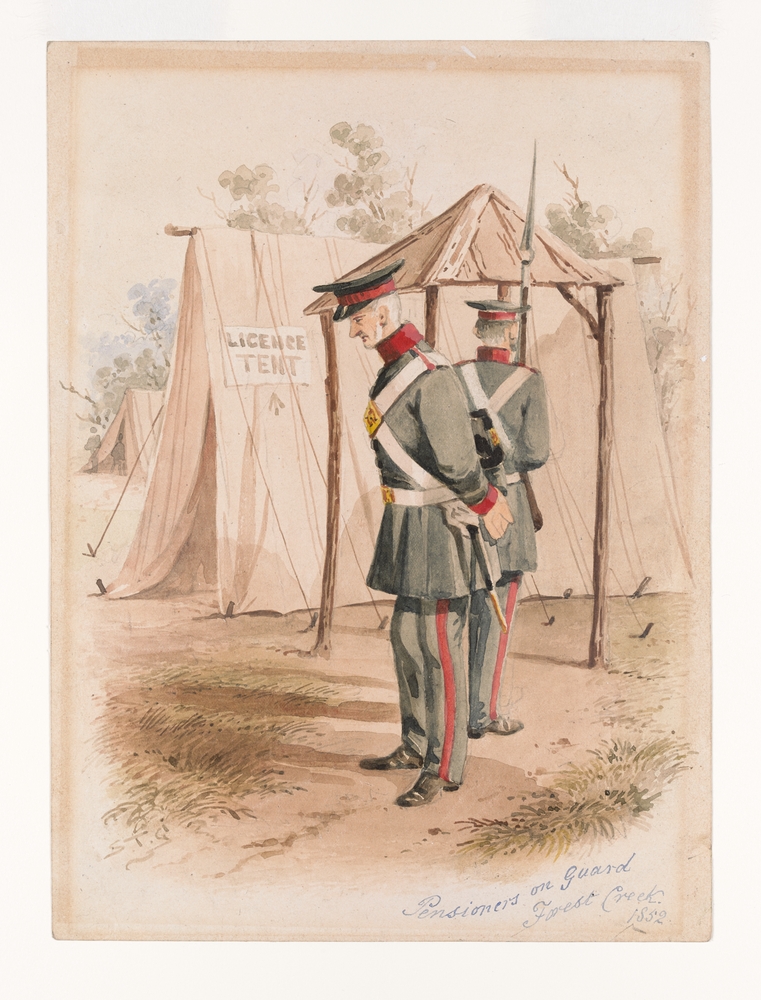

This watercolour by Samuel Thomas Gill shows two elderly men in uniform standing outside a licence tent. One has a rifle with a fixed bayonet. These 'pensioners' were military men who had retired from service and were recruited to help police the goldfields due to a shortage of regular officers. [Most of the police had deserted to the gold fields to try their luck - on one day in November 1851, 50 of the 55 Melbourne City Police resigned!]

Watercolour by Samuel Thomas Gill, 1872. Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

Mounting tensions

Resistance to the licence fee spread throughout the fields. Miners’ Associations or Leagues were formed in several of the major goldmining areas in 1853 and 1854, urging reform of the licence system and fairer administration of the goldfields.

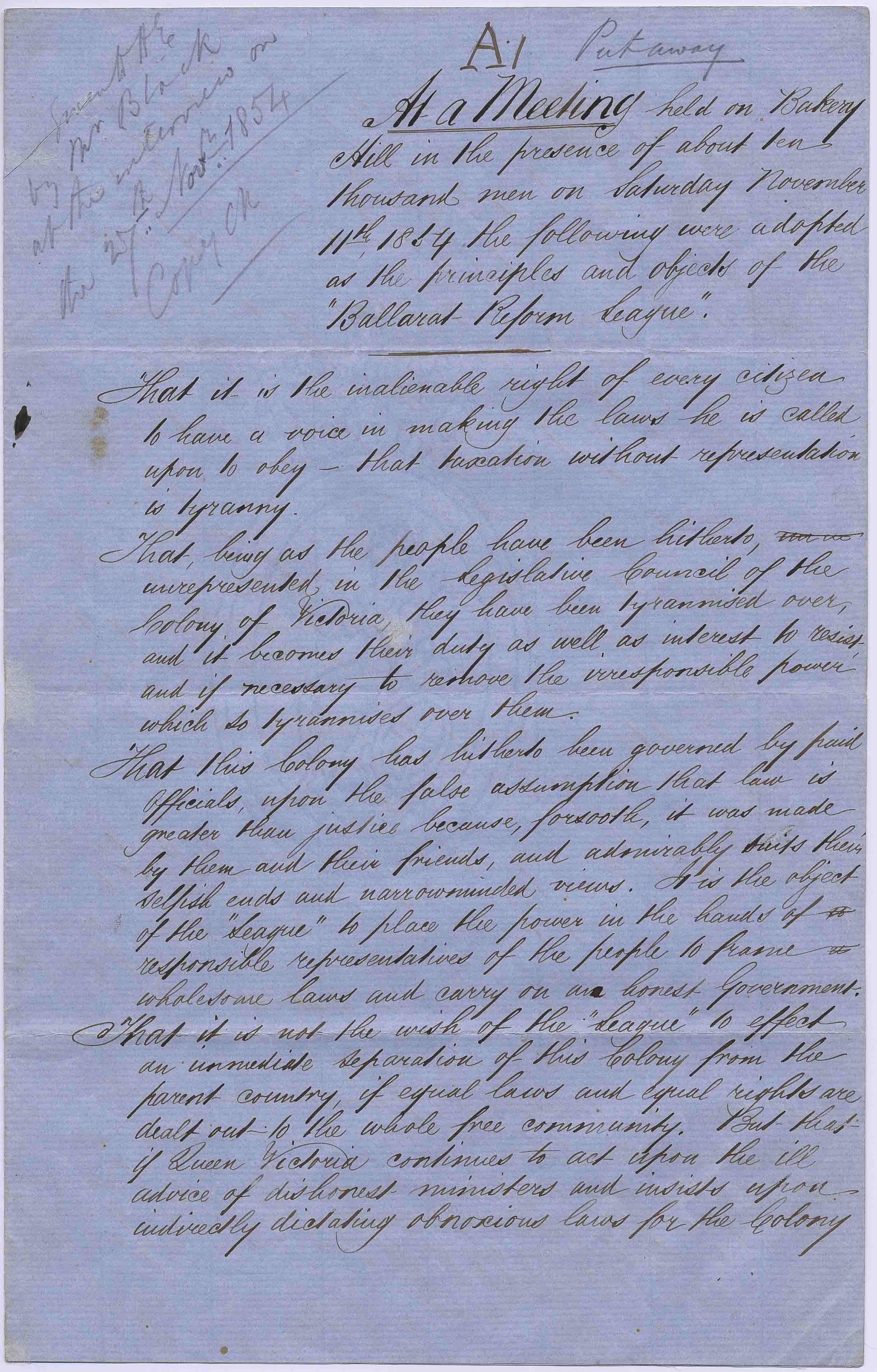

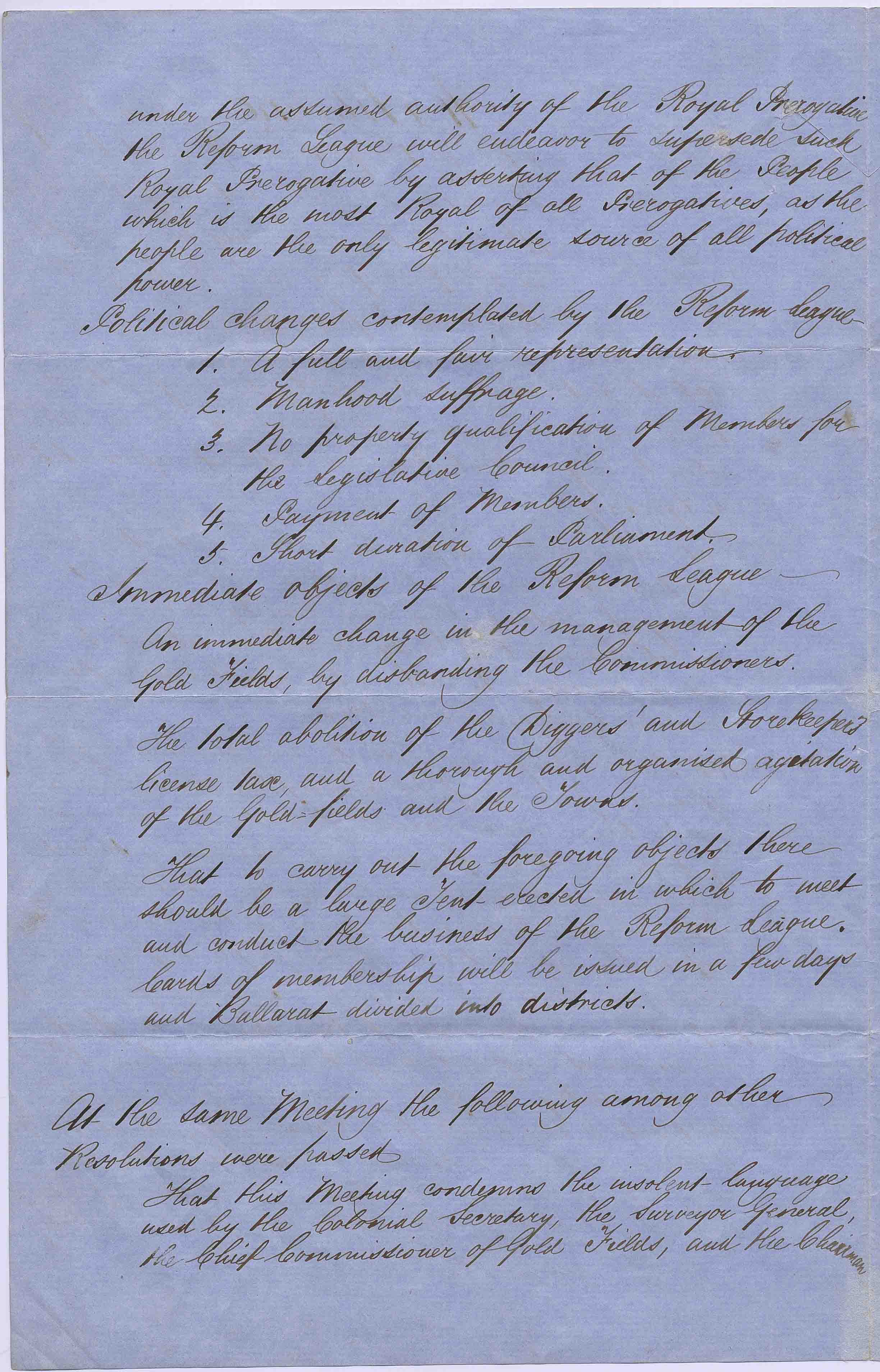

In November 1854, at a mass rally at Bakery Hill in Ballarat, the Ballarat Reform League was formed. League members took their inspiration from the British Chartist movement, in which some of the miners had been directly involved before coming to Victoria. (The Chartist movement was a step by the new working-class, born out of the Industrial Revolution, to improve their rights and gain political representation.)

The League drafted a four-page Charter summarising its principles and demands. Demands included:

- Free and fair representation in parliament;

- Manhood suffrage;

- The removal of property qualifications for members of the Legislative Council;

- Salaries for members of parliament;

- and fixed parliamentary terms.

This Charter was presented to Governor Hotham.

Tensions come to a head

But anger grew as the colonial government refused to compromise. On 29 November 1854 a meeting at Bakery Hill in Ballarat attracted more than 10,000 angry miners. The Southern Cross (‘Eureka’) flag was flown for the first time and licences were burned. The following resolution was passed:

‘That this meeting, being convinced that the obnoxious licence fee is an imposition and an unjustifiable tax, pledged itself to take immediate steps to abolish same by at once burning all their licences. That in the event of any party being arrested for having no licence, that the united people will, under the circumstances, defend and protect them.’

Eureka Stockade

On 30 November 1854 miners in Ballarat met again and elected Peter Lalor as their leader. They swore to fight together against police and military. Using timber from nearby mining shafts, they built a stockade and prepared to defend it.

On 3 December almost 300 mounted and foot troopers and police stormed the stockade. The miners were overpowered almost immediately. Some 22 diggers and six soldiers were killed.

The police arrested and detained 113 of the miners. Thirteen were taken to Melbourne to stand trial. However, many people in Victoria opposed what the government had done in Ballarat and one by one the 13 leaders of the uprising were tried by jury and acquitted.

After Eureka

In the aftermath of the Eureka uprising, Royal Commissioners investigated conditions on the goldfields. By April 1855, as a result of their recommendations, the government abolished the miner’s licence and introduced a miner’s right, renewable annually for £1. Although the constitution was yet to be passed, as an interim measure, twelve new seats were added to the existing Legislative Council, eight of them to represent goldfields electorates.

That it is the inalienable right of every citizen to have a voice in making the laws he is called upon to obey – that taxation without representation is tyranny.

In the language of the Charter and in its principal demands, the Ballarat Reform League drew on the immediate legacy of the Peoples’ Charter in Britain and on the rhetoric of various movements for democratic reform in Europe in the late 1840s. Its basic tenets were even older, drawing on the principles of the American and French revolutions and on even more ancient assertions of the ‘rights’ of citizens to have a voice in the way they were governed. It failed to convince Governor Hotham, however, who eventually moved against the miners in force at the Eureka Stockade.

In 2006, the Charter was inducted into the UNESCO Memory of the World register of significant historical documents.

Reproduced courtesy Public Record Office Victoria

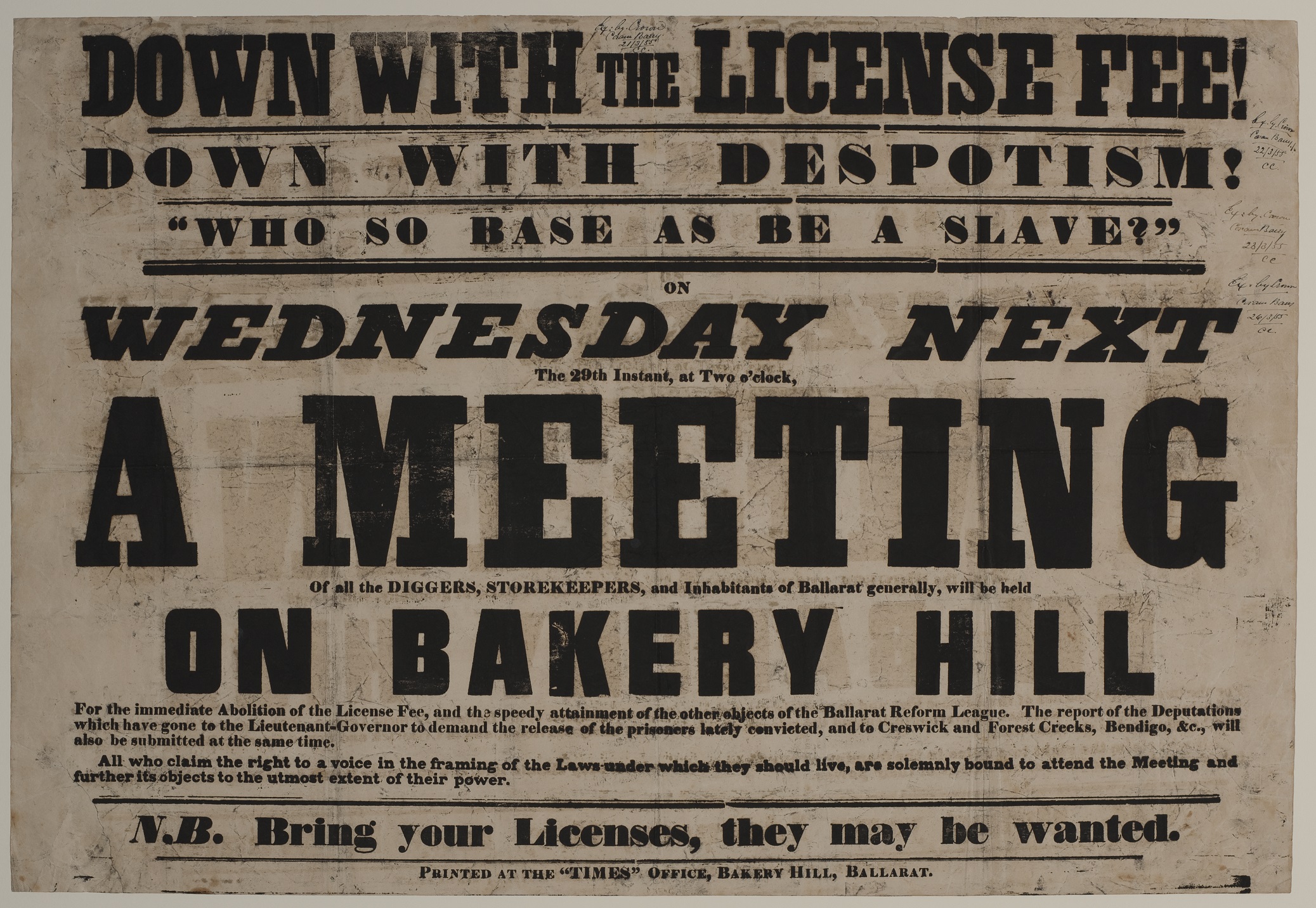

This poster called for a meeting of Ballarat miners on 29 November 1854. The language used was strong, showing the seriousness of the miners’ grievances.

It is said that ten thousand Ballarat residents attended the meeting. While some Ballarat Reform League leaders urged the crowd to use peaceful means to achieve their aims, there were angry calls for miners to burn their gold licences. The following day, about a thousand miners began constructing a rough stockade at the Eureka diggings.

Reproduced courtesy Public Record Office Victoria

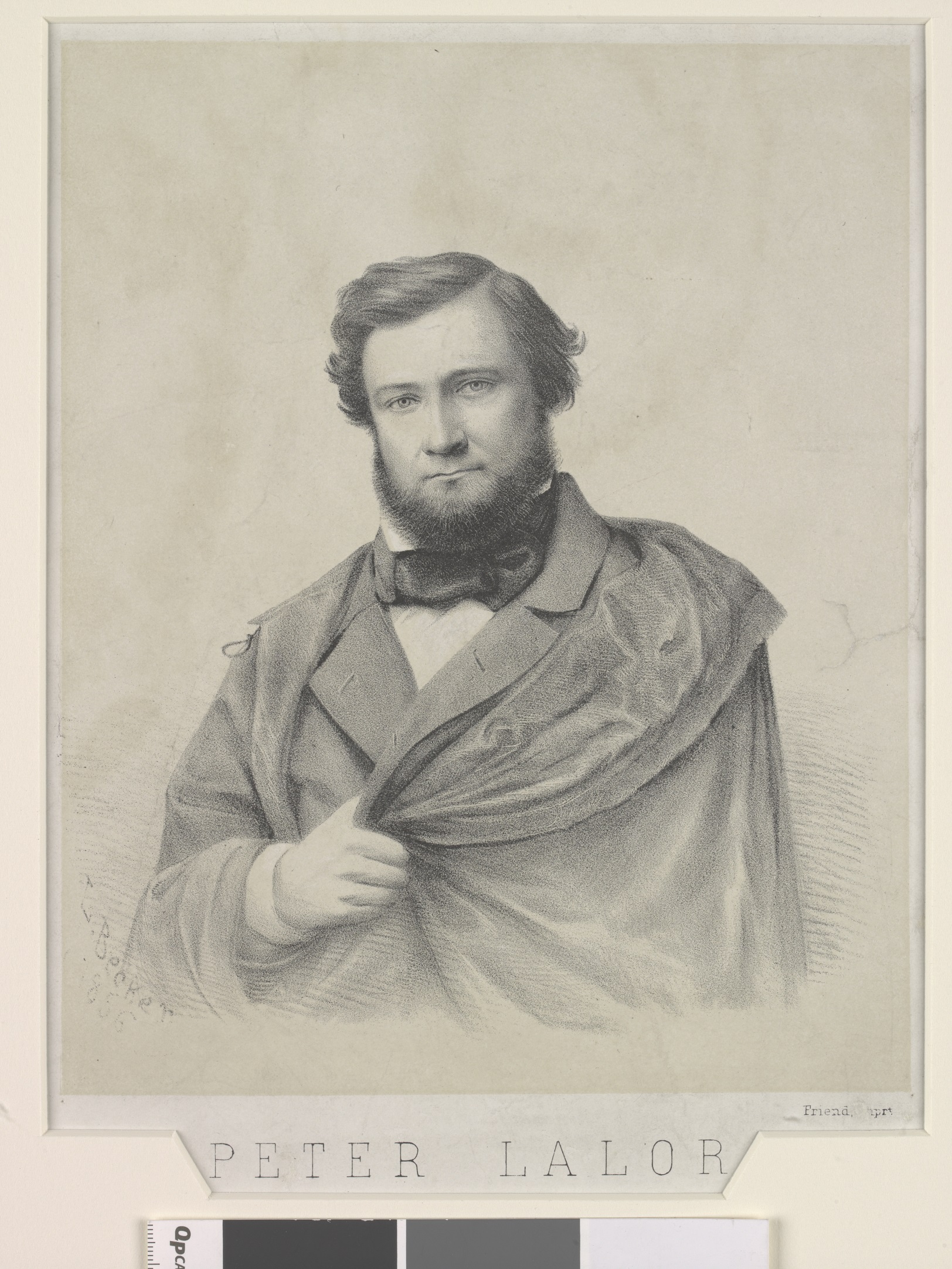

Irish-born Peter Lalor (1827–1889) emerged as a leader of the Ballarat miners in November 1854. He directed miners as they prepared their rough stockade at Eureka and swore to defend their rights. In 1855 the commission that Governor Hotham had appointed to inquire into the management of the Victorian goldfields recommended that miners should be represented in the Legislative Council. Lalor and John Humffray were elected to the Council in November that year. In 1856 Lalor became a member of Victoria’s first Legislative Assembly. He resigned from Parliament in 1887.

Lithograph by Ludwig Becker, 1856. Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

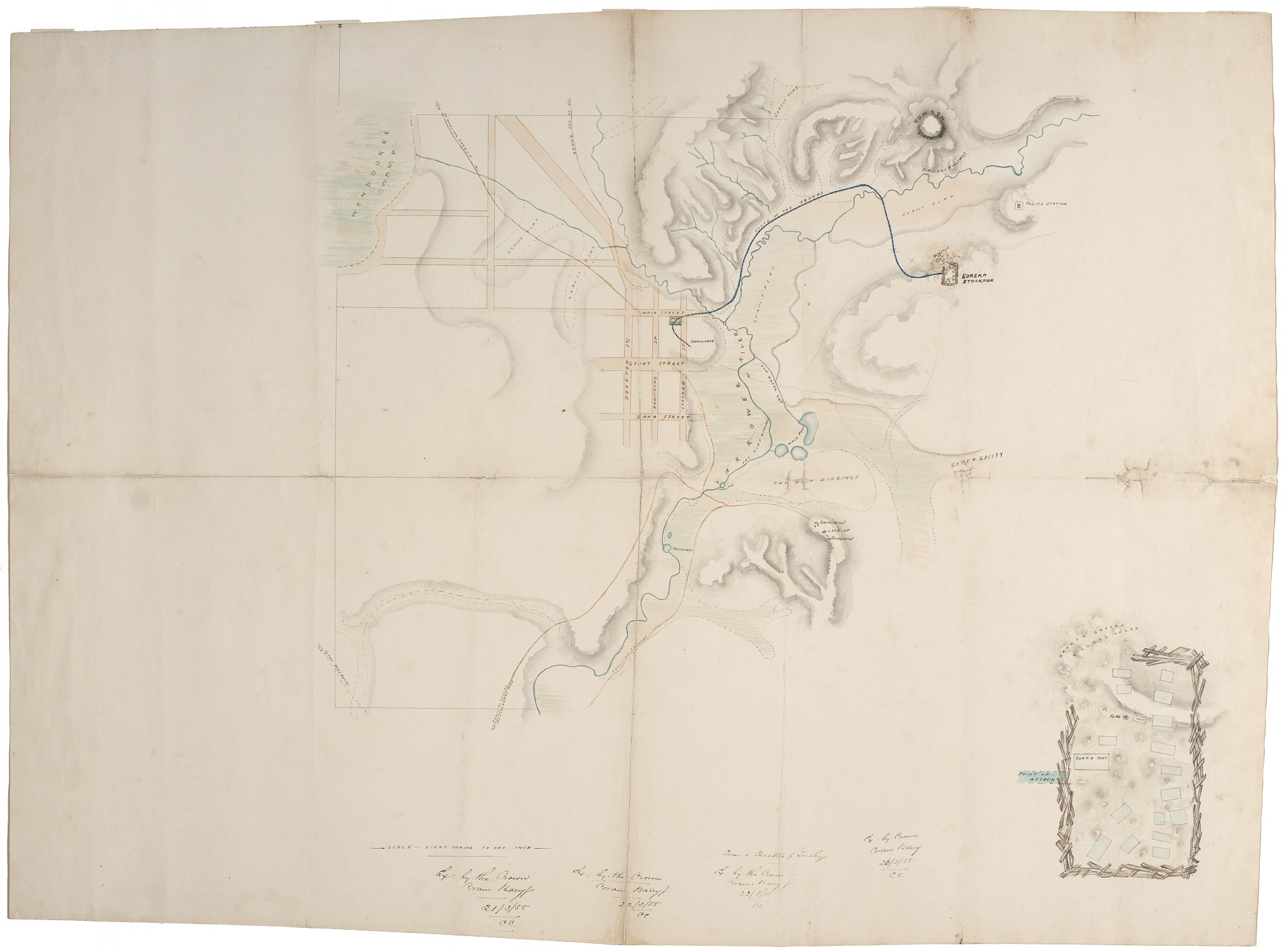

This map was used as an exhibit at the 1855 treason trials of thirteen stockaders. It shows the route taken by government troops from their camp to the miners’ stockade at the Eureka diggings in the early hours of 3 December 1854. It also includes a detailed drawing of the stockade itself. It is not known who drew the map and its accuracy was questioned in court. The exact location of the stockade remains a matter of debate.

Reproduced courtesy Public Record Office Victoria

![Diggers licenceing [sic] Forest Creek State Library of Victoria image.](https://www.oldtreasurybuilding.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Diggers-licenceing-sic-Forest-Creek.jpeg)