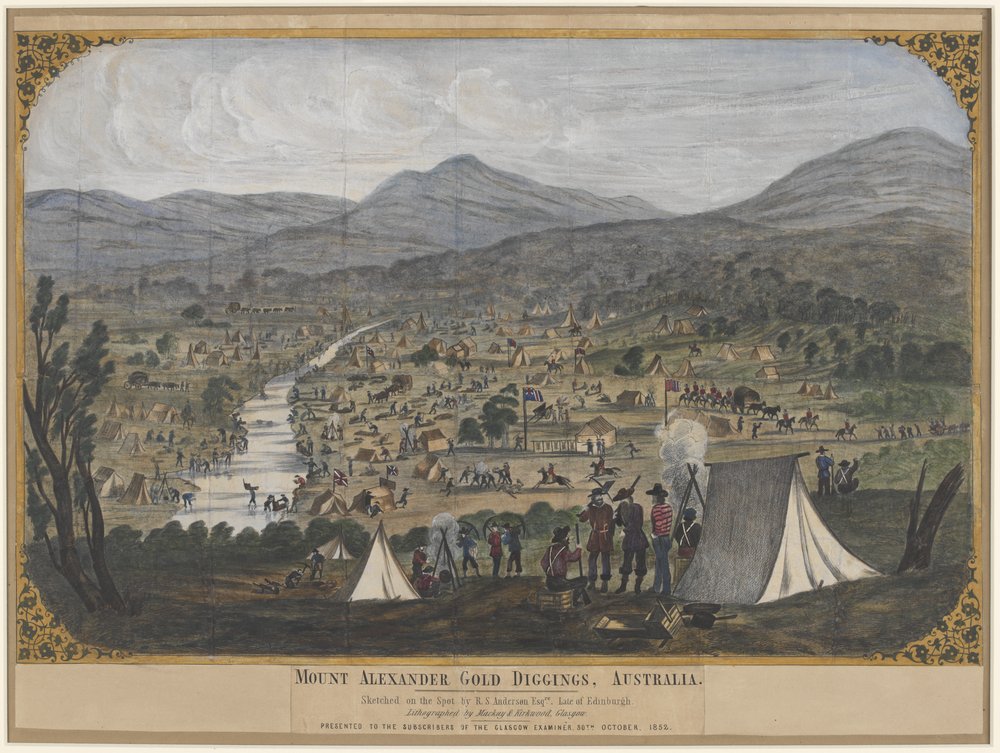

There are, we should say, about a thousand cradles at work, within a mile of the Golden Point, at Ballarat. There are about fifty near the Black Hill, about a mile and a half distant, and at the Brown Hill Diggings there are about three or four hundred more; to say nothing of hundreds on the ground not yet set at work. Allowing five for each cradle, the population within a radius of five miles must be a population of about seven thousand men.

Geelong Advertiser, 14 October 1851

‘…tubs, cradles, windlasses and wee-gees… all – all in motion – a perfectly confounding phantasmagoria of impetuous action and mire’.

Author and miner, William Howitt

At the fields a digger’s first task was to purchase a miner’s licence and peg out a small ‘claim’ of eight feet square (2.4m). Miners looked for two kinds of gold - alluvial gold, in the surface soil and the gravel and silt of creek beds, and buried gold, in the deep quartz reefs underground. It was the surface or alluvial gold that started the gold rush. For those who got there first, fortunes were literally lying on the ground!

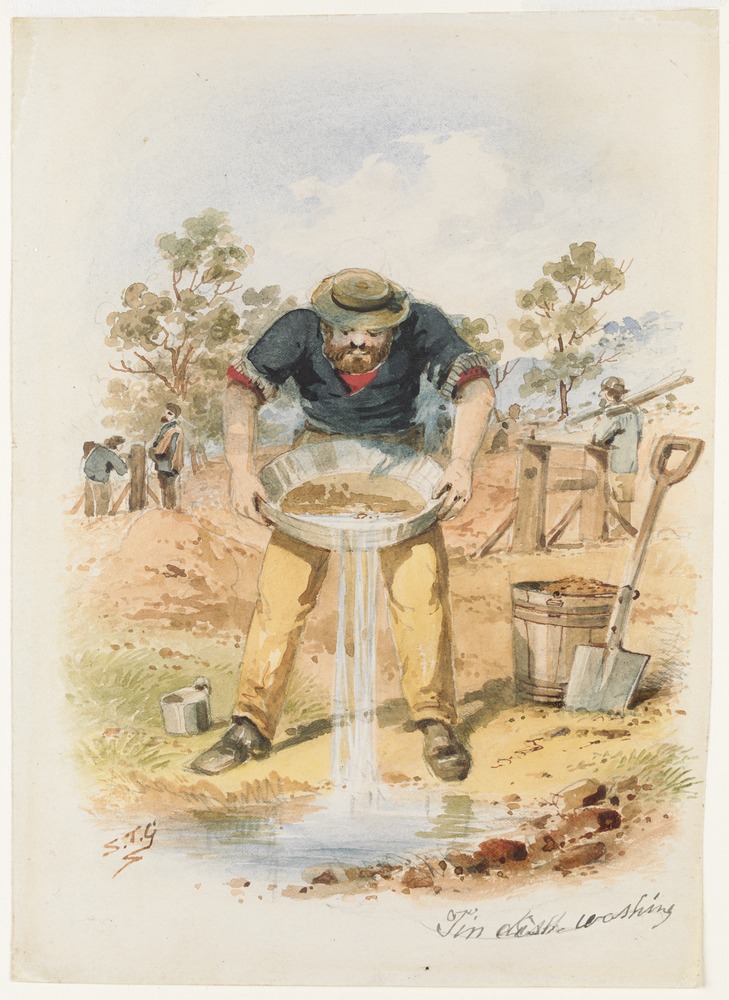

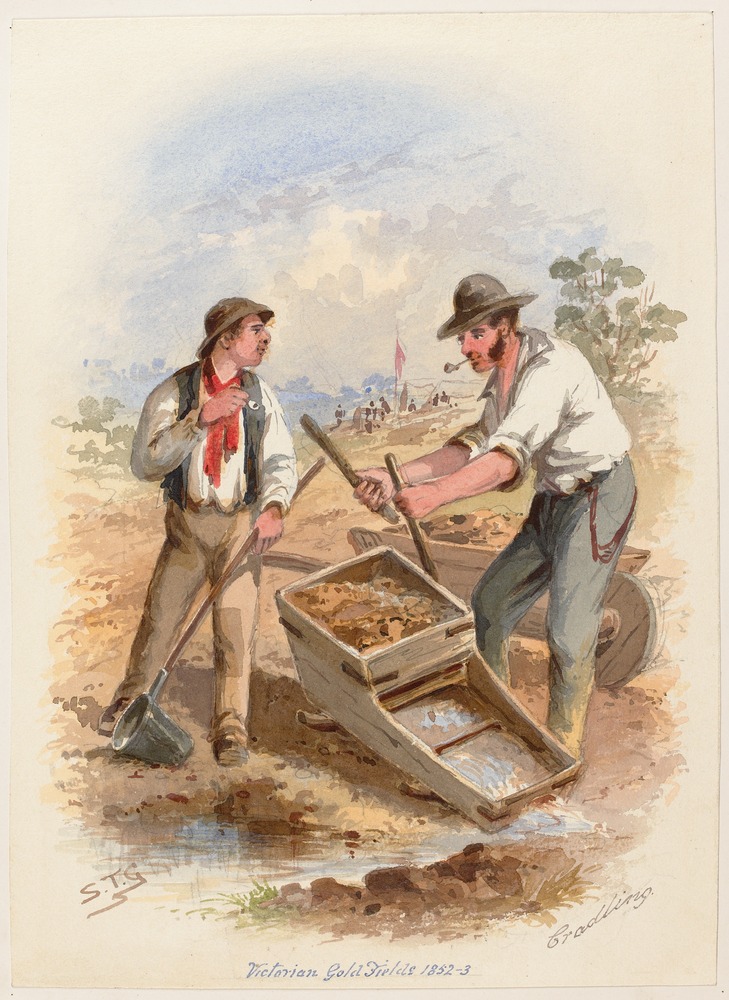

Alluvial gold

Mining shallow alluvial gold was straightforward. All you needed was a regular water supply, picks and shovels, pans, and a cradle like the one here. The top of the cradle was filled with soil and water, then rocked forcing water and soil through the sieve, leaving any gold behind. It was back-breaking work.

Alluvial gold could also be found at greater depths. Shafts were sunk, sometimes to thirty metres or more, dirt winched to the surface and put through a cradle. As holes deepened, miners formed teams to share the tasks of digging, raising and washing the dirt.

Buried gold

By the late 1850s the shallow alluvial gold was mined out and miners had to dig deeper. They looked for the ancient, buried rivers or ‘deep leads’, the gold contained in quartz reefs deep underground.

This type of mining required powerful machinery and by the 1860s most men on the Victorian fields were working for wages, employed by mining companies. They alone could command sufficient capital to reach this underground gold.

Tin dish washing by Samuel Thomas Gill, 1872

Watercolour reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

Cradling by Samuel Thomas Gill, 1869

Watercolour reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

Alluvial gold washing, Mt Alexander goldfields, Victoria by John Skinner Prout, 1852

Courtesy National Library of Australia

Mount Alexander gold diggings, Australia, by R.S. Anderson Esqre, 1852

Courtesy State Library Victoria

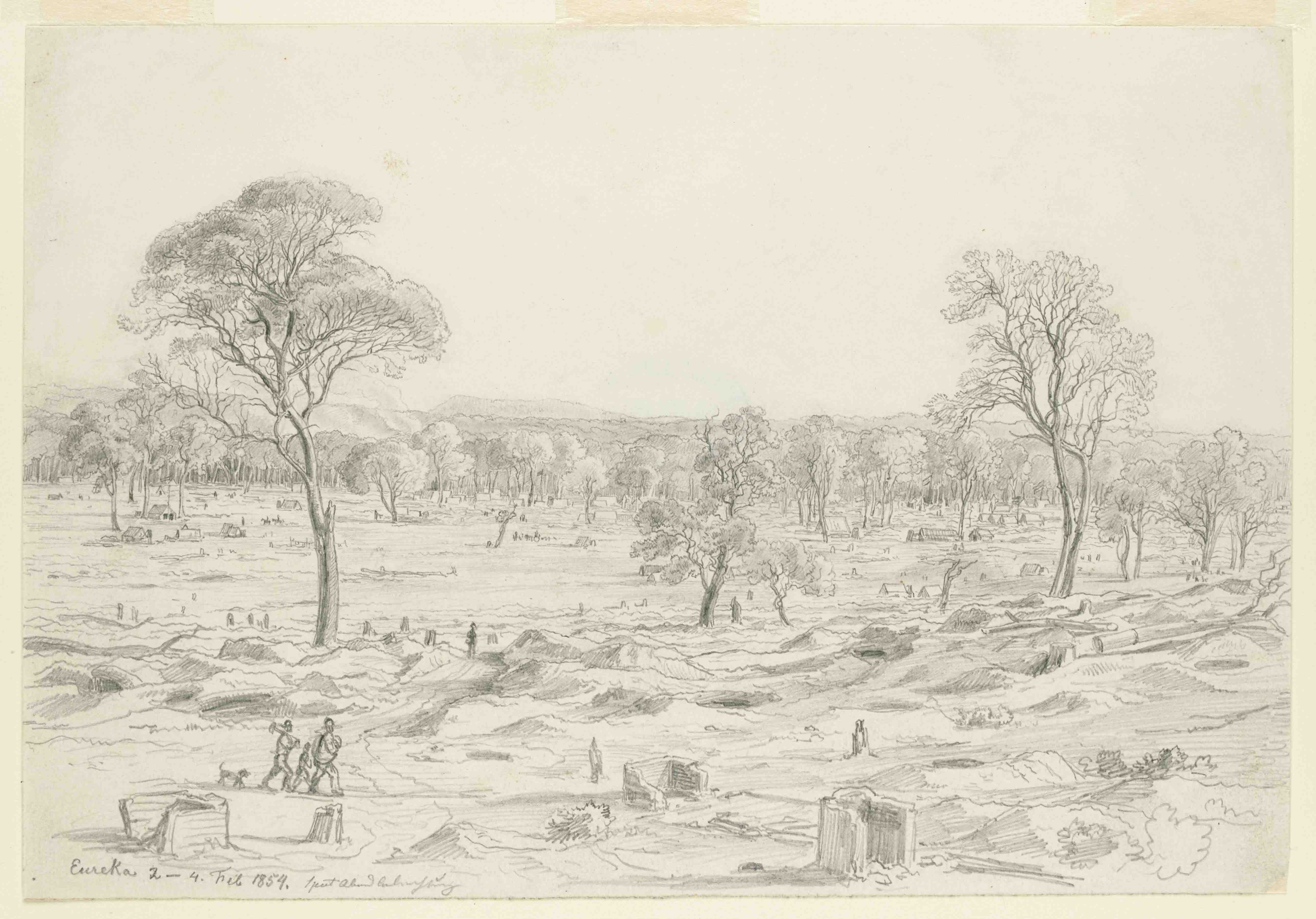

‘Every tree is felled… every feature of Nature is annihilated’, William Howitt

Both alluvial and deep lead mining took its toll on the environment. Trees were felled, scrub cleared, holes dug everywhere and pristine creeks fouled. In 1852, artist and miner Eugène von Guérard wrote: ‘Just a year since my arrival at Ballarat, and how changed it all is in that short time. Stretches of fine forest transformed into desolate-looking bare spaces, worked over and abandoned. In many parts, where a year ago all was life and activity, there now is a scene of desolation.’

As settlements spread over the interior First Nations people were further displaced, their hunting grounds destroyed and their waterways polluted.

Sketch by Eugene von Guérard, 1854. Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

Author: Ann Wilcox