It is an easy thing to say “I’ll go to the diggings” but no one knows what it means till he has tried it.

Author and miner, William Howitt

Object 2 in Gold Rush: 20 Objects, 20 Stories is a watercolour by Samuel Thomas Gill, on loan from State Library of Victoria. In this work, Diggers on the way to Bendigo, Gill captures the essence of the long, dusty and sometimes dangerous trek to the Victorian goldfields.

Below is a transcript of the talk presented by Dianne Reilly during Rare Book Week on Sunday 1 July 2018.

‘The artist of the goldfields’, Samuel Thomas Gill, always known as ST Gill, was one of Australia’s most significant and best-known artists in his own lifetime, and his delightful sketches and watercolors have not lost their charm or their significance since they were created. However, his fame has taken a very long time to materialize as published records of his life and work. Over the years, Gill’s sketches and watercolours have been made accessible in a piecemeal way through a number of published biographical sketches and studies:

- In 1913, historian A.W. Greig first launched the artist in the public domain by publishing an article about him in the Victorian Historical Magazine, published by the Historical Society of Victoria.

- The next history to be published was not until 1971 when Keith Macrae Bowden privately published his monograph Samuel Thomas Gill, Artist.

- Gill’s Australian Sketch-Book of 24 lithographs, first published in 1864-65, was reissued to great acclaim by the Lansdowne Press in 1974.

- Almost a decade later in 1981, literary historian Geoffrey Dutton’s liberally illustrated ST Gill’s Australia coincided with a revival of interest in Australia’s colonial art, ensuring that Gill reached his rightful place in the story of Australian art.

- The following year (1982), The Victorian Gold Fields 1852-3, edited and introduced by historian Michael Cannon, was published by Currey O’Neil with the State Library of Victoria. This focused on 40 watercolours by Gill, commissioned by the State Library in 1869.

- Gill’s engravings for Victoria Illustrated 1857, originally issued by Melbourne publisher Sands and Kenny, were published as a reprint with Nicholas Chevalier’s 1862 companion volume by the Lansdowne Press in 1983.

- In 1986, the Art Gallery of South Australia released S T Gill: The South Australian Years 1839-1852.

- Fast forward to 2015, and State Library Victoria and the National Library of Australia joined together to present a major touring exhibition Australian sketchbook: Colonial life and the art of ST Gill. This was the first-ever retrospective to focus comprehensively on the life and work of Gill, and through his art, it provided a window onto everyday life on the goldfields and in the bush, cities and towns of 19th-century Australia.

- The exhibition was accompanied by a wonderfully-researched book S.T. Gill & His Audiences by Emeritus Professor Sasha Grishin of Australian National University, who had also curated the exhibition. This is the most recent major publication to be devoted to Gill and presents a radical reassessment of one of the most important figures in Australian colonial art.

The Old Treasury Building Museum’s current exhibition Gold Rush: 20 Objects 20 Stories presents the turbulent tale of Victoria’s gold rush through the individual stories of 20 objects, and three of S T Gill’s paintings are there to convey the story through his eyes.

Gill is renowned for his many sketches and watercolours depicting the daily life of diggers in Australia in search of that elusive metal - gold. Michael Cannon, has written that Gill was a born reporter, and much more than that, he was a creative interpreter of human existence – and especially life in colonial Australia. How did this career begin?

Adelaide

ST Gill was 21 years old when he arrived in Adelaide from England on board the ‘Caroline’ with his parents and younger brother and sister in December 1839. Born in Somerset on 21 May 1818, he was the eldest of five children of a Baptist minister and schoolmaster, Rev. Samuel Gill and his schoolteacher wife Winifred. As a boy, he had some training as an artist since his parents recognised his extraordinary talent, but after the death from smallpox of two of his siblings, the Gill family emigrated to South Australia. Gill was to spend 41 years in Australia before his death in Melbourne in October 1880.

He soon established himself in Adelaide as a portrait painter, placing several hundred advertisements for his studio in the South Australian Register and other newspapers. Not only did he solicit ‘the attendance of such individuals as are desirous of obtaining correct likenesses of themselves, families, or friends’, he also advised that he could create ‘correct resemblances of horses, dogs, etc. with local scenery etc. executed to order’.

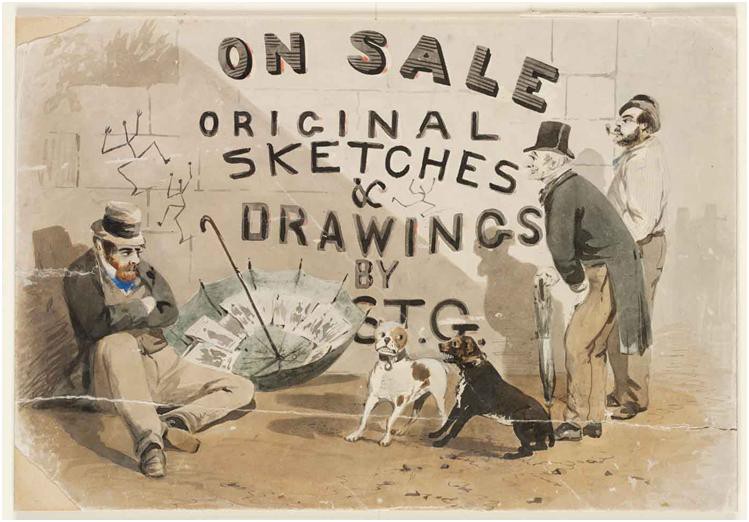

Gill loved animals and the bush, and he seemed more at home in the saddle in rural Australia than he did in town. He was particularly fond of dogs, and felt a certain affinity with them. We know he owned dogs for most of his life and frequently inserted them into his paintings and lithographs. It was his practice to include his own dogs in the scenes he was drawing. He often used dogs as personifications through which to create a commentary on human society. ‘Invalid Digger’ (1852) is one of his most compassionate images of the digger down on his luck, with his adoring sheep dog. The digger’s hand is bandaged and his injured foot is shown bare and swollen, but the viewer’s attention is specially drawn to the loving relationship between the canine and his master. In a late self-portrait, titled On Sale Original Sketches & Drawings by S.T.G. (c.1870) (pictured below), the artist shows himself seated against a brick wall, next to an inverted umbrella full of his drawings, which he offers for sale. We seem to have seen his canine companions shown here in earlier sketches, especially the American bulldog, with his own unique personality, and they are his only companions. As in so many of his other self-portraits, he is slumped on the ground, while the potential buyers look quizzically at him as if not knowing what to make of the art.

Gill understood horses well and painted them brilliantly. One of his works shows Tim Whiffler, winner of the 1867 Melbourne Cup. In many of his sketches and paintings, it is immediately apparent that he knew a great deal about the anatomy of the horse and its technique of movement. An accomplished horseman himself, it was as a result of being in the saddle so much as he travelled through the South Australian countryside that his work began to assume an Australian style.

He was able to communicate in his sketches the distinctive characteristics of the Australian landscape, so much so that the Adelaide newspaper, the South Australian Register praised his style in glowing terms: ‘It was only the other day we had the opportunity to see some of his bush scenes. They are the most vivid and lifelike of any that have been before presented to us. He gives the true idea of South Australian scenery. Nothing is exaggerated, nor any point lost’. In fact, Gill is considered by many art historians today to be ‘the first artist to give visual expression in his works to the emerging Australian character’.

ST Gill recorded the impressive departure of the explorer Charles Sturt from Adelaide in 1844 in search of a route into Central Australia, his large painting breathing life into the scene he viewed of colonial pomp and ceremony, showing bystanders amazed by the spectacle, and others on horseback viewing the parade, while their dogs, full of confidence and personality, dart hither and thither.

Gill also visited that other great pioneer traveller Edward John Eyre at his home on the Murray. Both explorers – Sturt and Eyre – had their own sketches of their observations while exploring ‘worked up’ by Gill to illustrate the published accounts of their journeys: Eyre’s Journals of Expedition and Discovery into Central Australia (journey 1840-1; published 1845) and Sturt’s Narrative of an Expedition into Central Australia (journey 1844-46; published 1849).

Horrocks Expedition

In 1846, Gill joined as a draughtsman the ill-fated expedition to the head of Spencer Gulf of explorer John Ainsworth Horrocks. Although the journey was curtailed by the death of Horrocks – tragically, he had accidentally shot himself when his bad-tempered camel moved unexpectedly – Gill went on to produce 33 watercolour paintings documenting the doomed expedition. These were included among 62 works of various artists exhibited in February 1847 in the Adelaide ‘Exhibition of Pictures: The Works of Colonial Artists’ at the Council Room in North Terrace. Following the exhibition, these pictures were raffled for a guinea a piece.

Some of Gill’s most memorable works from his twelve years in South Australia are his streetscapes of a fledgling Adelaide which had been surveyed and laid out on a grid pattern (similar to Melbourne) by Colonel William Light in 1837. [Just an aside: it was Colonel Light whose father, also Colonel Light, Colonel Francis Light, who had laid out George Town, the capital city of Penang, one of the Malay states, now a UNESCO World Heritage site since 2008.]

Gill drew the Adelaide streets, including Hindley Street and Rundle Street (below), largely surrounded by bush and parklands, less than a decade after the city had been established. As art historian, Professor Sasha Grishin has noted in his recent book ‘one can say that Gill’s early urban images were propagandist and promoted the image of the colony of South Australia as a thriving English transplant in the antipodes’. These streets are shown as swept perfectly clean, and populated by well-dressed perfectly happy labourers, peddlars and the occasional merchant or landowner. Especially the dogs have not a care in the world! The reality was, of course, somewhat different, with drought and lack of water often reducing these streets to dust bowls.

While in South Australia, Gill produced his first lithographs, a medium which was to become a vital part of his art practice in later years. His ‘Heads of the People’ series was published in 1849, documenting the images of 22 prominent Adelaide men including the Mayor and an Immigration Agent with, as he described them, ‘unmistakeable likenesses’. While the portraits were no doubt accurate impressions of these luminaries, there is an element of the caricature in them, Gill exaggerating the striking characteristics of each one so as to create a comic effect.

Gill was also greatly interested in the new art of photography, a newspaper reporting in November 1845 that ‘A daguerreotype has been sent to the colony, and is in the hands of Mr Gill, the artist. It appears to take likenesses as if by magic…We understand that Mr Gill will soon be prepared to show us as we are, and beyond a doubt, his wonderful machine will be “the glass of fashion and the mould of form”’. With numerous photographers becoming established in Adelaide about this time, it appears that Gill’s attempts to earn a living from daguerreotypes failed and he soon sold the apparatus.

Gill was a prolific and popular artist, and he quickly developed a high profile in South Australian colonial society. Before he left Adelaide in 1851, he was commissioned to paint a number of watercolours to publicise the short-lived copper mining boom to the north at Kapunda and Burra Burra, soon to be replaced in 1851 by another mining boom – this time for gold - in Victoria.

Some historians consider that this rather shy and sensitive artist was overshadowed by painters of less talent than himself. He was a prolific artist, but known to be a very poor businessman who did not follow up on debts that were owed to him. He did try to work his way out of the insolvency he had filed for in September 1851 with a number of paintings and lithographs, including fine equine images. His financial downturn, together with an unfortunate inflammation and paralysis of his right hand for several months when he was unable to use brush or pencil, no doubt led to his decision to depart South Australia to seek his fortune on the Victorian goldfields.

Victoria

From 1851, Adelaide was virtually depopulated as able-bodied men hurried to Victoria. Gill himself arrived at the Mount Alexander (Castlemaine) diggings early in 1852. In this area of central Victoria, the surface and shallow workings, especially at Forest Creek, were very productive. It was reported that, in nineteen days, three diggers had uncovered here 360 ounces of gold, and another group had obtained £1000 worth of gold in a mere two weeks. The yield was so rich that diggers even deserted Ballarat for the Mount Alexander field. This was at a time when more than two tons of gold were arriving in Melbourne each week from Ballarat and the new diggings around Castlemaine and Bendigo.

In his watercolour Diggers on the way to Bendigo, 1852 (below) which is on display in the Old Treasury Building exhibition, Gill depicts prospectors on the road from Melbourne. They are carrying their blankets and the essential mining equipment of tin dish and cradle. In fact, they had to pass north through the Black Forest, where travellers were sometimes waylaid by highwaymen. They had to be well-armed and often had the protection against thieves and bushrangers of a fierce dog.

Gill was with a group who dug for gold at Pennyweight Flat, near Castlemaine on Forest Creek where many Adelaide diggers had gathered. Forest Creek had its Adelaide store and Adelaide restaurant, and Adelaide gold-office where South Australian diggers could deposit their gold for safe escort home. However, Gill soon gave up mining to indulge his passion for recording all aspects of life and work around him in sketches and watercolours. His images of Forest Creek are strong in detail and topographic in style. The viewer is treated to detailed mining scenes, and yet there are intimate glimpses of diggers as they maintain a semblance of normal life in these unfamiliar circumstances.

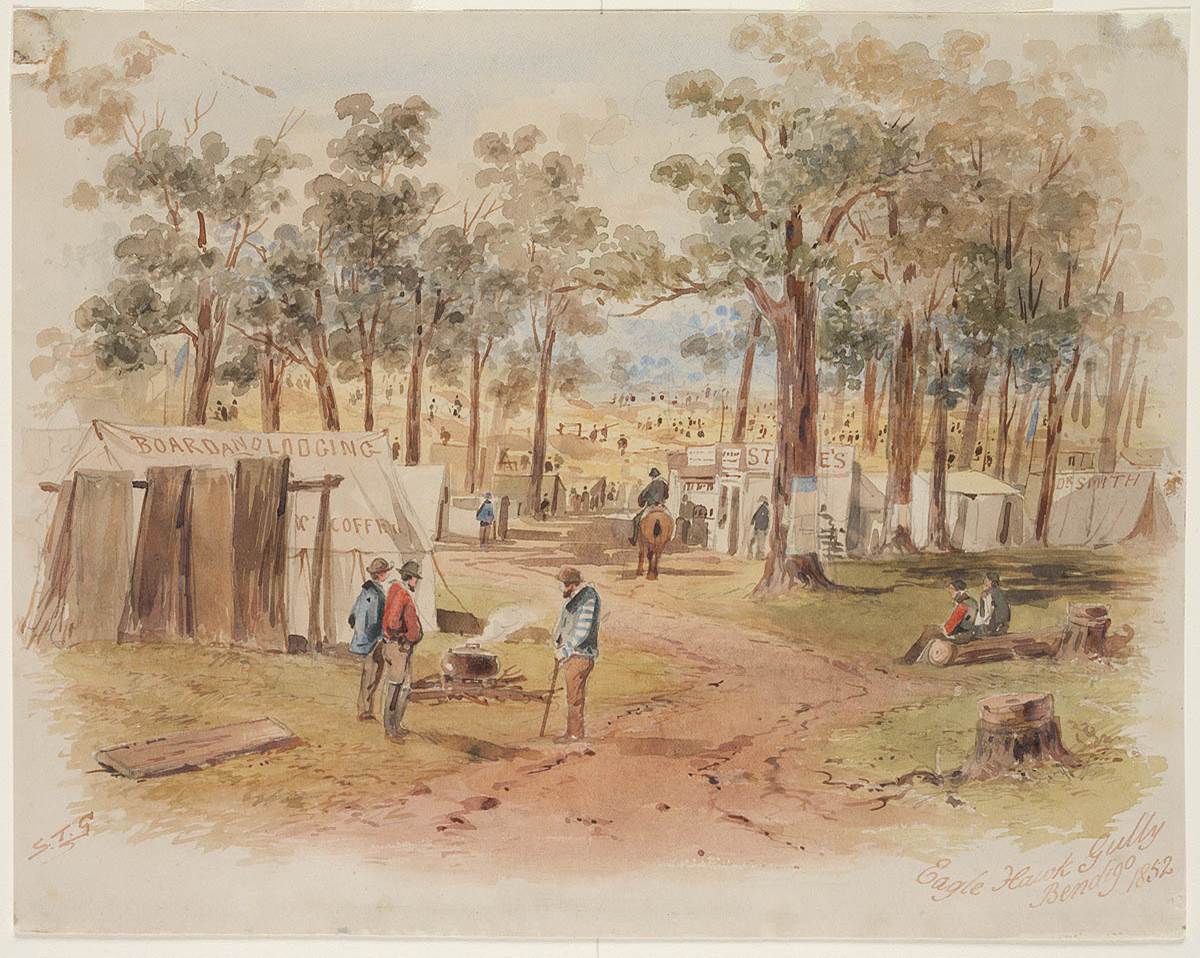

‘Eagle Hawk Gully, Bendigo’ is perhaps one of Gill’s finest paintings. This work shows a panoramic view of the settlement created following the discovery, in April 1852, of large deposits of gold there, only five miles from Bendigo itself. Hastily erected board and lodging tents such as the one to the left usually contained rough stringy-bark camp stretchers available for five to ten shillings a night. For a further five shillings, lodgers were supplied with the universal mutton, damper and tea for breakfast, lunch and dinner. Directly across the main road was the store for general supplies, and Dr Smith’s medical tent.

Another lucrative trade was sly-grog, selling liquor without a license. It was illegal to sell liquor on the goldfields, and if it was discovered, the vendor was fined £50, and his tent was burned down. In spite of this, the trade flourished. Sly-grog sellers did a roaring trade from what they called their “lemonade” tents, most likely paying the police to look the other way while they served spirits and other alcohol to diggers. The writer of 'A Lady’s Visit to the Gold Diggings of Australia in 1852–1853' (1853), Mrs Ellen Clacy, described the female owner of one such establishment as ‘a most repulsive looking object’, but I think Gill was kinder in his rendition of the women publican in his pictures.

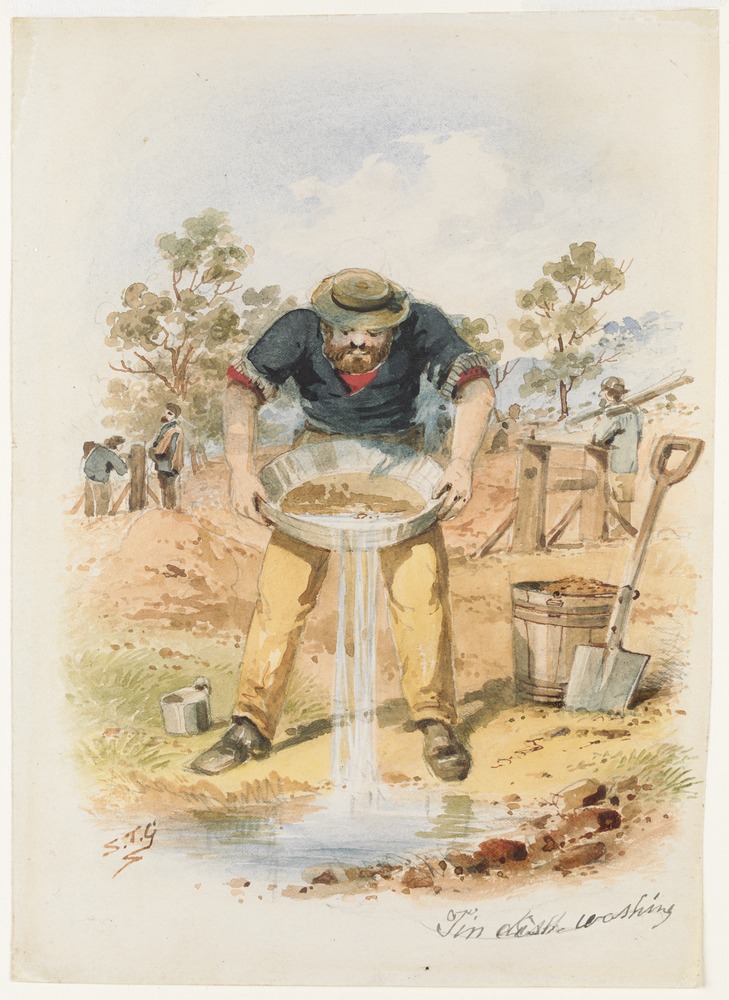

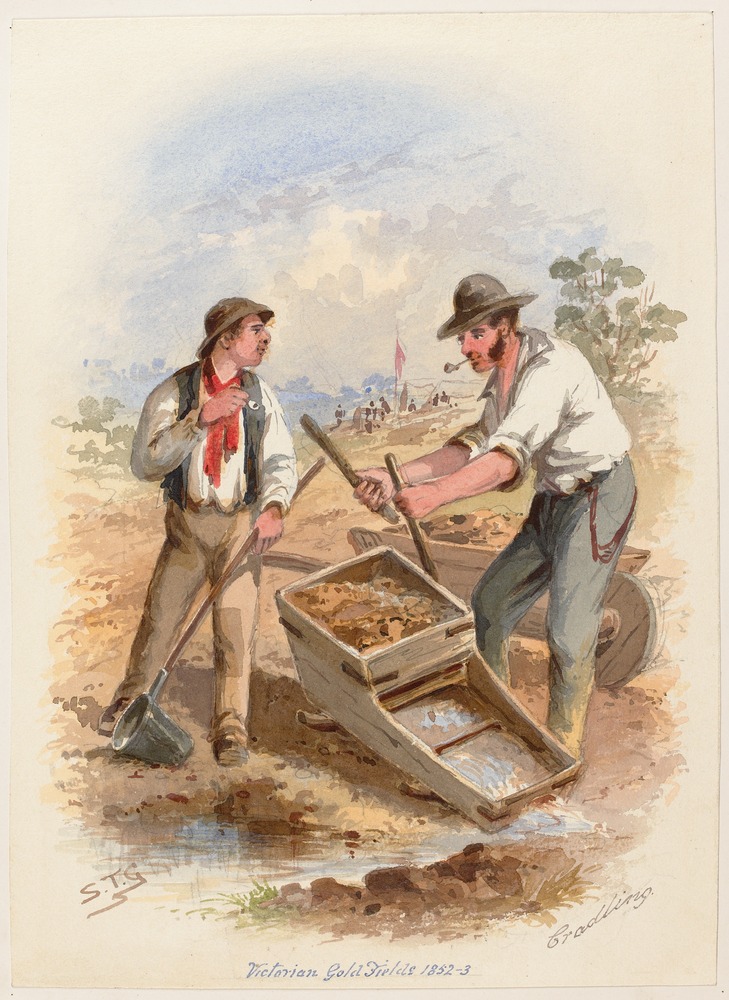

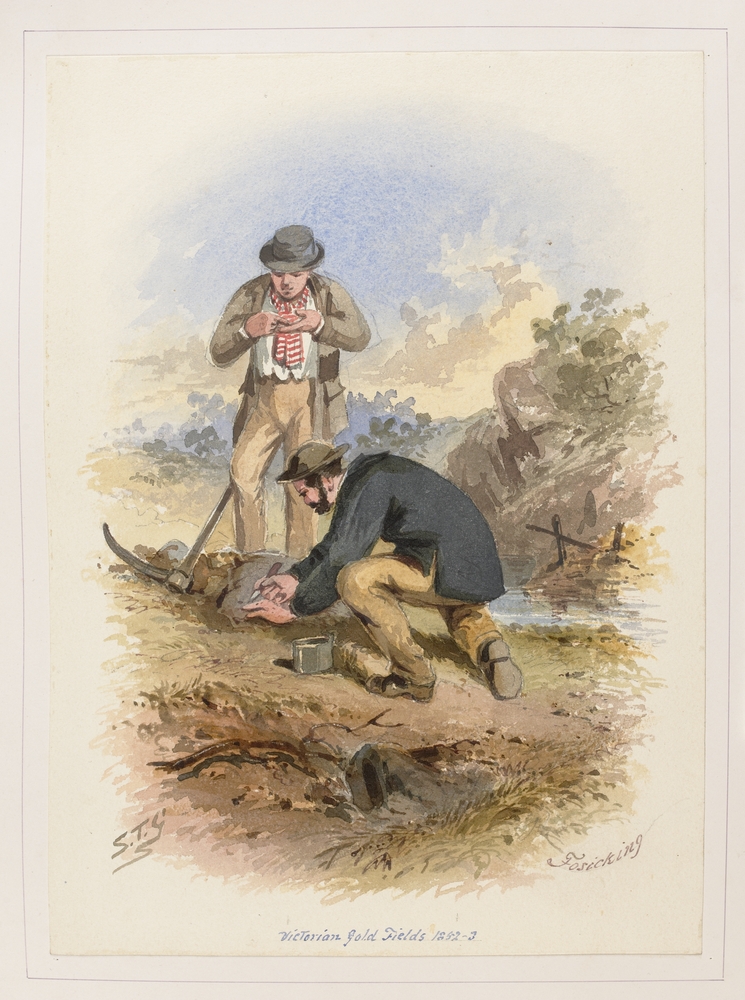

Gill was fascinated by all he saw. There was so much of human interest as he rapidly sketched the population at the diggings, including Diggers of High Degree and Diggers of Low Degree. His close-up views of the processes involved in surface gold mining are documented for posterity in Tin Dish Washing, Cradling, Puddling and Fossicking (below).

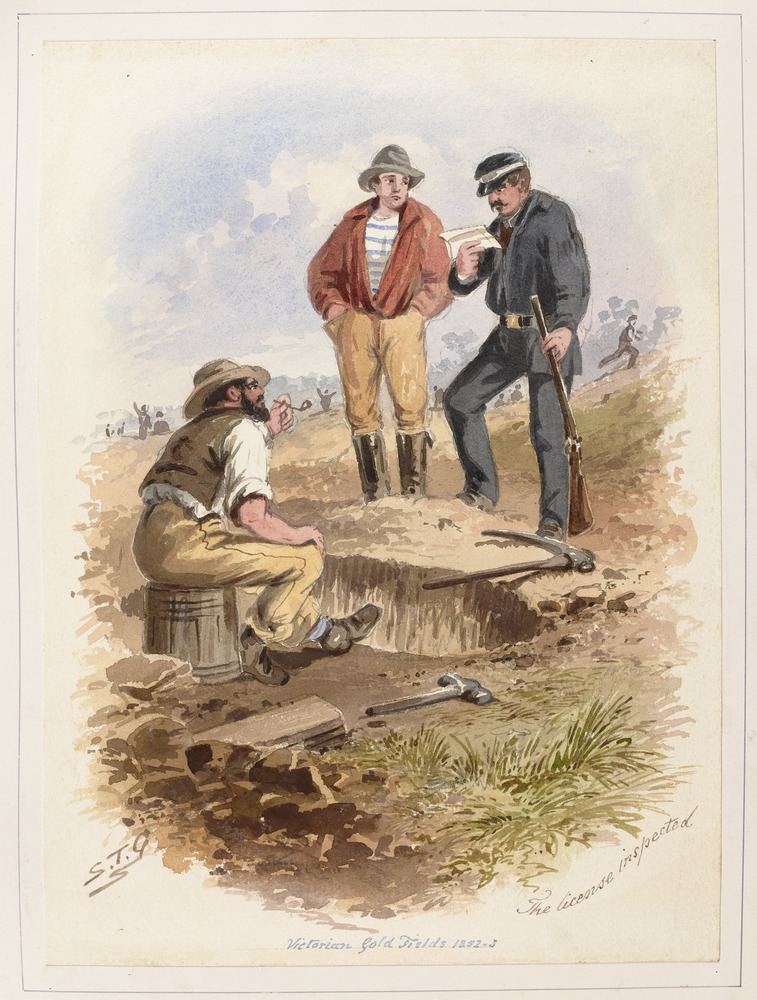

There was, however, a great deal of unrest at Ballarat, foreshadowing the more serious events heading to the bloodshed at Eureka Stockade in 1854. The licence fee of 30/- per month had been introduced by Lieutenant-Governor Charles Joseph La Trobe as a source of revenue to meet the expenses of maintaining order on the goldfields, and of establishing much needed roads and other services. The penalty for mining without a licence was a fine of five pounds, and for further offences, imprisonment for up to six months. La Trobe, in a momentary lapse of good sense, increased the licence fee in 1853 to £3 per month, but quickly reduced it again in the face of uproar from the miners. We can clearly observe the presence of the law on the goldfields through Gill’s eye-witness records in The licence inspected (below) and Diggers licensing, Castlemaine camp.

Licence boundaries for mines were strictly enforced, and the approach of the police was signalled by the cry of ‘Joe! Joe!’ as miners without licences scrambled to escape the grasp of the law. ‘Joe’ or ‘Charlie Joe’ were terms of derision for the Lieutenant-Governor whose name appeared on so many government notices on the goldfields, and it became synonymous with the oppression many diggers felt from what was seen as an unsympathetic government.

The Mount Alexander Gold Escort beautifully captures the watchful atmosphere prevailing as the valuable gold nuggets and gold dust were safely transferred to Melbourne. The original Old Treasury Building in William Street, demolished in 1922, received early consignments of gold for safe-keeping, but this building was replaced by the Old Treasury building as we know it, designed by nineteen-year-old architect J.J. Clark, and built between 1858 and 1862.

Gill’s first two series of lithographs of Victoria, each of 24 black and white sketches, were published by Macartney and Galbraith in Melbourne in 1852 as Sketches of the Victorian Gold Diggings and Diggers as they are. The first series of 24 sketches also appeared in London in August 1853 under the imprint of H.H. Collins & Co., and Piper Brothers & Co.

In Gill’s sketches, women and family members are often shown as active participants in mining activities, as in Zealous Gold Diggers (below) where a woman nurses her baby in one hand, while she rocks the gold-extracting cradle with the other, and her little boy ladles water into the cradle. In the later engraving from this picture, she has her small daughter this time, handling a shovel quite effectively, while her husband pours buckets of water into the cradle.

After nearly two years on the goldfields, Gill turned to Melbourne where he must have considered that better opportunities for work awaited him.

Here he recorded life and happenings in this rapidly growing city, where more curious scenes awaited his paintbrush. In a fine watercolour, Dress Circle Boxes, Queen’s Theatre, Lucky Diggers in Melbourne, 1853, the interior of the theatre, completed in 1845, is vividly portrayed, packed with miners and their rather doubtful ‘lady’ friends at an evening performance. The viewer observes the interaction between the more prosperous miners in the boxes and the more impecunious diggers in the stalls. This picture is similar in many ways to his later Subscription Ball, Main Road, Ballarat, 1880.

Gill’s The Digger’s Wedding captured the euphoria of the successful gold miner who returned to the city to establish himself in metropolitan life. Bride and groom are seen driving through the streets in an open carriage, the best man quite overcome from celebrating, and offering a glass, or is it a bottle of champagne to the bemused driver. The hire of a carriage was six pounds a day and champagne cost at least three pounds a bottle, often the cost of such celebrations amounting to £100 or even £200.

Gill was a keen eye-witness to the development of the City of Melbourne which prospered enormously as a result of the gold rushes. His etchings document a Melbourne, traces of which still remain today, as in the Mechanics’ Institution, and Sandridge and Williamstown.

Sydney

Despite the fact there are very few details available about Gill’s personal life, it is known that he went to Sydney by ship in May 1856 in the company of a lady. They established themselves in George Street where he gave art classes. He was soon in demand as a sports artist, contributing to the popular sporting paper of the era Bell’s Life, and publishing lithographic views of scenery in and around Sydney. Gill also gave painting lessons when he moved Woolloomooloo, and one of his pupils, William Garling junior, paid his teacher a fitting tribute:

His brush subjects had a great fascination for me and though his work perhaps was not of the highest order, I doubt if anyone could put the scenes on paper in a more realistic manner. Even now, I think the Gum trees he used to paint (when he was in proper form) were truer to nature than those of other artists – he was particularly good in the foliage – and was most successful in getting the peculiar blue green of the leaves.

In 1857, Victoria Illustrated, a volume of steel engravings based on Gill’s drawings, was jointly published by Sands and Kenny of Melbourne and Sydney, and Thomas Brown of Geelong. Gill was the artist, but engravers Arthur Willmore and James Tingle created the plates. While no text accompanied the illustations, Gill sketched the developing city of Melbourne and surrounds, with the addition of views of regional areas including Ballarat and Bendigo and rural scenes. Post Office, Melbourne, and City Police Station.

Then, in 1862, Gill was commissioned by Dr J.T. Doyle, an Irish medical doctor, lecturer and stage performer, to create a sketchbook detailing Doyle’s experiences in Australia. Gill was not to be acknowledged as the artist – he was really the ‘ghost artist’. As it happened, the planned lithographed album never materialised. While Doyle added his own inscriptions to each watercolour image, Gill surreptitiously and subversively claimed ownership of the works by neatly painting his initials ‘S.T.G.’ in many of the pictures. The watercolours Gill created for Doyle are in the collection of the State Library of New South Wales.

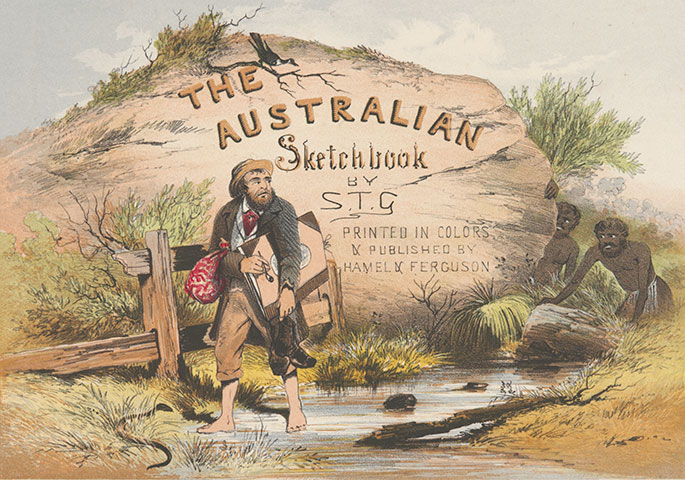

By 1864, Gill had returned alone to Melbourne where he undertook his major publication, The Australian Sketchbook. This appeared in print partially that year, the complete work of 24 chromolithographs or printing in colour, a medium still in its infancy, being published in 1865 by Melbourne printers Hamel and Ferguson. While bearing some similarities in subject matter to Doyle’s sketchbook of two years earlier, in this work, each image is signed with Gill’s traditional ‘S.T.G.’. Gill shows himself as being quite at home in the bush in this volume of rural rather than urban scenes, depicting mostly Indigenous life and the outback.

It was only in 1869 that the Trustees of the then Melbourne Public Library (now State Library Victoria) had the foresight of commissioning Gill to paint scenes of the Victorian gold fields as he recalled them. The album he produced was titled The Victorian Gold Fields 1852-53, and the original images are as fresh and beautiful today as they were when Gill painted them.

Sasha Grishin is rather convincing when he puts forward the theory that Gill’s ties with the bohemian set in Melbourne, in particular his friendship with the writer Marcus Clarke, then working as a librarian at the Public Library, and the journalist and art critic James Smith, later a trustee of the Library, may have led to Gill’s most important commission of the late 1860s. At a Trustees Meeting, as noted in the minutes for 8 April 1869, a modest sum of 15 shillings was advanced to Gill for incidental costs of paints and paper, towards the commission of 40 watercolours depicting life on the Victorian goldfields, as he remembered them in 1852 and 1853. The sum of £53/10/- was paid for the 40 pictures plus a title page, on receipt of the work. The Library then had the sketches bound into a single large volume, now considered one of the great treasures of the State Library collection. It was published by the State Library in 1982 and is regrettably, now out of print.

State Library Victoria has acquired over the years more than 600 works by S.T. Gill. The National Library of Australia, State Library of New South Wales and the Art Gallery of South Australia also have rich collections of Gill’s watercolour paintings, sketches and published graphics.

Doing the Block

One of Gill’s most important pictures is a watercolour and pencil sketch with Chinese white highlighting on buff paper titled Doing the Block, Gt. Collins Street.

The work is annotated on the verso with the precise date and time that Gill completed it: ‘10 July 1880: 3.30pm’. It is fresh and as full of life as so many of his earlier works, and as Professor Grishin has noted, it ‘shows a mastery undiminished by his failing health. Gill completed it only 3 months before his death on 27 October 1880’.

To refresh your memory, the Block was that section of Collins Street between Elizabeth and Swanston Streets which, from the late 1840s, was a popular venue for those in fashionable society to parade up and down and to meet their friends and acquaintances. Today, it is recalled in the Block Arcade, which was named in 1890 to recall the earlier era and its well-heeled and perhaps snobbish society.

The growth of a wealthy and leisured class gave rise to these activities, much to the disapproval of Melbourne Punch, which referred to the ladies as ‘these hot-house plants, these honeyed exotics, these brilliant butterflies’, and would have preferred them to cultivate, ‘those various household arts so essential to make good wives’. The gentlemen who engaged in such perambulations were also severely dealt with: ‘The male portion likewise exemplify what is imagined to be the perfection of uselessness’.

While perfectly conjuring up the Melbourne scene in Collins Street in July 1880, I think we can also see here elements of the caricature, a skill which Gill possessed to a high degree. The scowl on the face of the lady on the left – had she seen someone wearing a hat similar to her own, or met someone she would rather have avoided? The paperboy – isn’t he a delight? – his barefooted sprint to make a sale so well captured. And the dogs – the greyhound/whippet meets the not so well bred terrier. This is Gill at his best!

Death

On 29 October 1880, the Melbourne Daily Telegraph newspaper reported:

A fearfully sudden death occurred yesterday afternoon. About half past four, a man, name unknown, about forty years of age, of slender build, 5ft. 8in. in height, with reddish beard, was observed to fall on the Post-office steps. Constable Connolly, who was on duty, at once had him placed in a cab for the purpose of having him taken to the hospital, but he expired almost mmediately. In his pockets were found a purse, key, and a book on which was written the name of Davies and Co., chemists, and several bills on which the name ‘Gill’ was written. The body now lies at the hospital dead-house awaiting identification and an inquest.

It was only later that evening, when the body was formally examined, that hospital-prescribed pills bearing his name were found in the pockets of the deceased. Gill had been attending the Melbourne Hospital for some time as an outpatient for a heart complaint and rarely travelled without his medications.

Unlike the present day, the inquest into Gill’s death took place the day after his demise. This was reported in both the Argus and the Age, the cause of death being cited as a rupture of an aneurism in the aorta. It seems that, on the day of his death, he had gone to the office of the architect Arthur Peck for some drafting work. However, Mr. Peck, on noticing that his hands were shaking, sent him home. He was observed at the General Post Office stumbling and falling against one of the pillars. The constable, who had sent him to the hospital in a cab gave evidence that he was “in the most filthy state”, and another acquaintance referred to him as having been ‘an habitual drunkard’. However, as the inquest deposed, ‘the cause of death was the rupture of an aneurysm of the aorta’. Sasha Grishin’s research has revealed that ‘Aortic aneurysm was a frequent cause of death in Melbourne at the time, and it was generally associated with high blood pressure, and a family history of heart problems’… ‘He may have drunk. He may have drunk to excess. But … he didn't die of a drink-related illness. He had a ruptured aorta, a heart attack. The post-mortem showed his liver was in very good condition."

Gill’s parents died when relatively young, his father aged 60, and his mother at 54, ‘so the artist’s breathing his last at the age of 62 was in keeping with the general family life expectancy’.

Burial

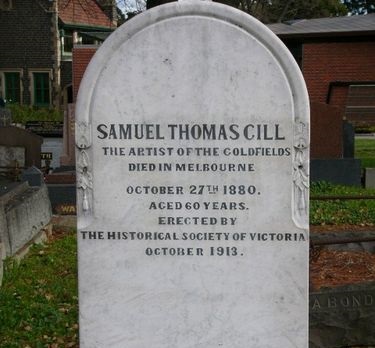

Gill was buried in a communal grave at the Melbourne General Cemetery. It was only in 1913 that the Historical Society of Victoria opened a public subscription to fund the removal of the artist’s remains to a private burial site with an appropriate headstone:

Samuel Thomas Gill

The Artist of the Gold-fields

Died in Melbourne, October 27th, 1880

Age 60 [sic] years

Erected by the Historical Society of Victoria, October 1913

Conclusion

Despite the fact that his life was undoubtedly, at times, very difficult and his circumstances trying and tragic, it was S T Gill who, so brilliantly, often conveyed in a light-hearted or even comic, or at times, sad way, the life styles of those he met and the landscapes they inhabited. The appeal of his art lies in the fact that he was able to document the past in its tiniest details, to give us today a picture of the past which is as fresh as it was at the time when he wielded his paintbrush. An obituary in the Melbourne journal Tabletalk in 1891 described his talent:

He was an absolute master of his materials, whether it was a simple black lead pencil, a brush full and flowing with Indian ink, or colours, bright, clear, pure and certain in their tones and gradations.

Without exception, S. T. Gill is Australia’s best known and most appreciated artist for evoking the colonial period of our history, especially the gold rush era. He drew history in the making for the most part, or history as he clearly remembered it. His output was vast, although it was not of an even standard. Some of it was good and some of it was very good!