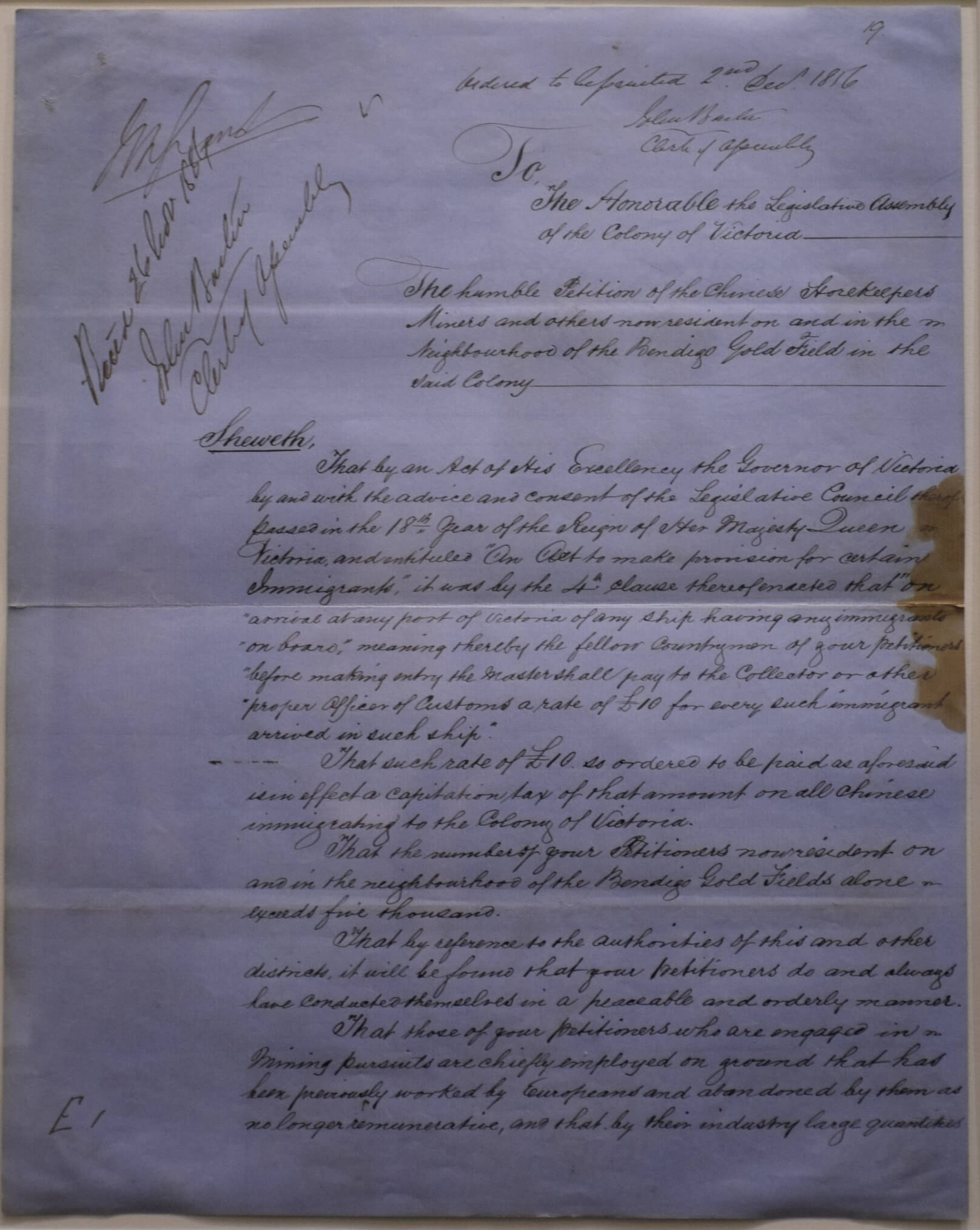

The humble petition of the Chinese Storekeepers, miners and others now resident on and in the neighbourhood of the Bendigo gold fields in the said Colony, ordered by the Legislative Assembly to be printed 2 December 1856

By late 1858 the population of the Victorian goldfields had reached 150,000. Over half were British immigrants: 40,000 were Chinese. Fleeing violence, famine and poverty in their homeland, Chinese gold seekers called Australia the ‘New Gold Mountain’.

Racism on the goldfields

Chinese miners faced discrimination on the goldfields from the start. Their appearance, dress and language set them apart and other miners were quick to label their cultural and religious practices ‘barbaric’.

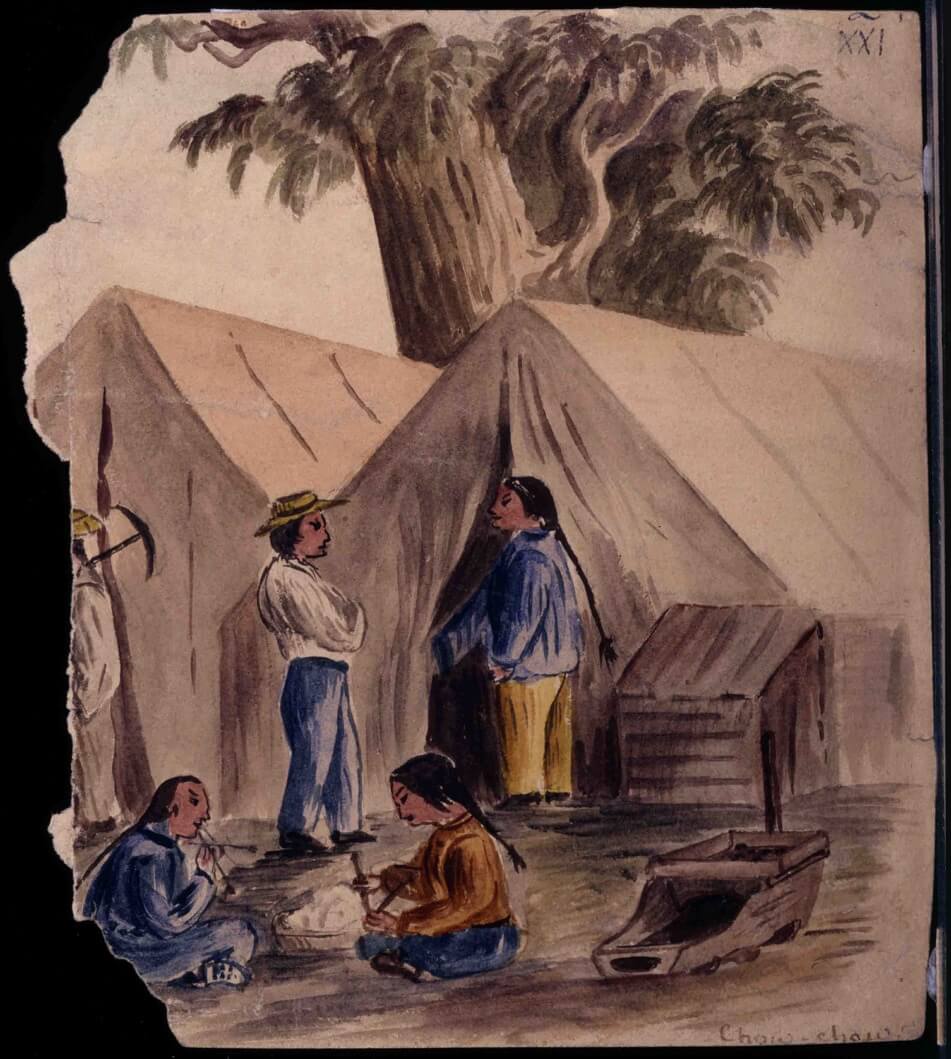

Working the fields

The Chinese worked as teams, often re-working ground abandoned by European miners. They were patient, even sweeping the floors of abandoned huts. They sometimes found gold others had missed. However unfairly, this became another source of conflict.

Restricting the Chinese

As the number of Chinese miners on the goldfields grew, so did public demand for their numbers to be restricted. In 1855 Victoria passed An Act to Make Provision for Certain Immigrants, the first of its kind in Australia. The Act imposed a capitation (poll-tax) of £10 on every Chinese arrival, and restricted passage to one Chinese person per ton of ship’s cargo.

To avoid the tax ships began to sail instead to Adelaide, Kingston and the small seaside town of Robe in South Australia. From there, the Chinese trekked 500 kilometres to the Victorian goldfields – a journey taking many weeks. It is estimated that 17,000 Chinese, mostly men, walked from Robe.

The Chinese voice

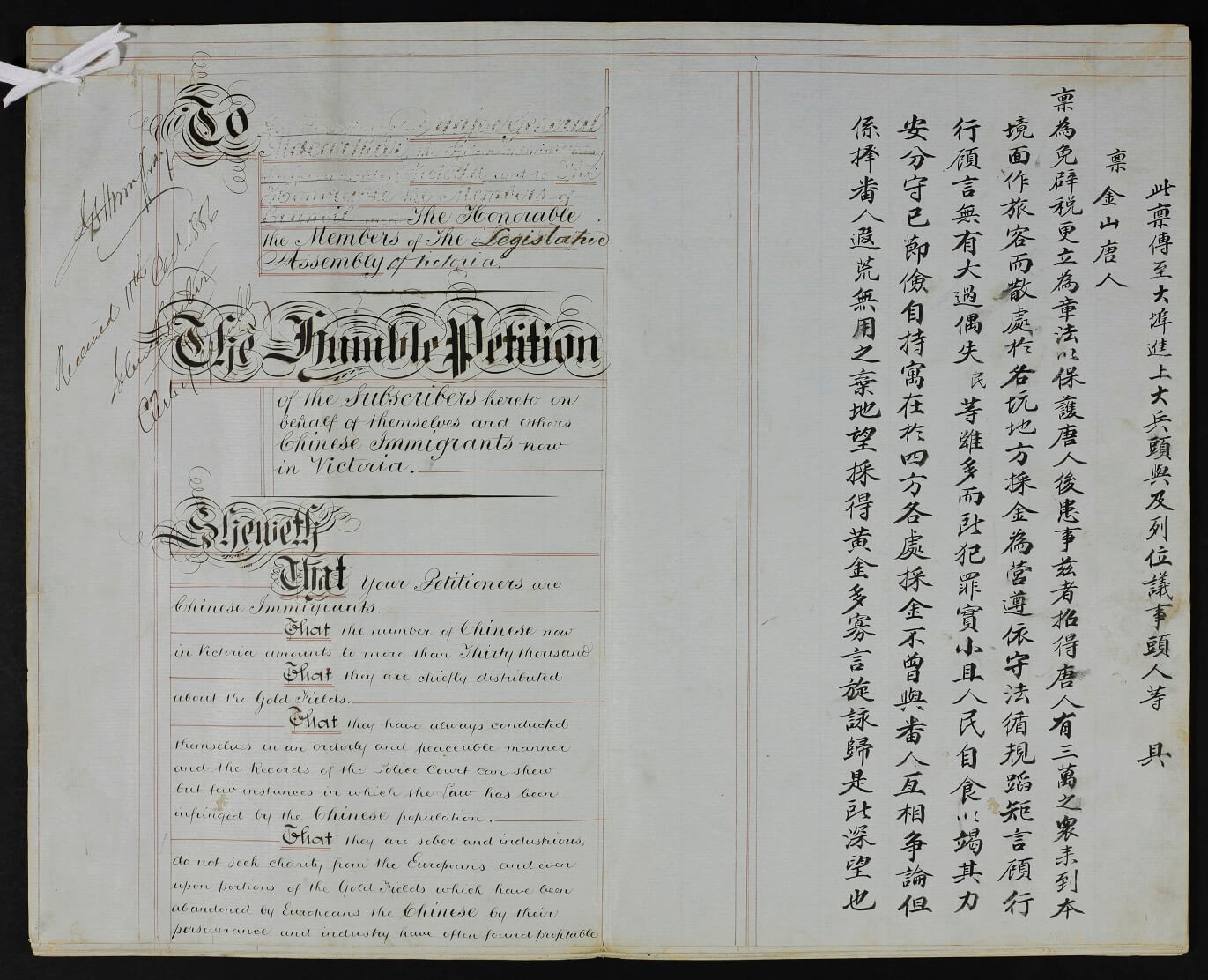

Many petitions protesting the £10 tax were sent to the Victorian government.

The petition on display in Gold Rush: 20 Objects, 20 Stories carries more than 5,000 signatures. It emphasises the positive character of the Chinese community, their ‘peaceful and orderly manner’ and the financial contribution they made to the colony. It points out that the entry tax was often evaded by landing in South Australia, and questions the perceived economic threat the Chinese posed to other miners, especially as they often worked abandoned ground.

Manuscripts such as this petition provide valuable insights into the adoption of constitutional protest by the Chinese community and help to document their participation in Victorian life.

Chinese diggers arrived at the Victorian goldfields in large numbers from the mid-1850s. In just two years the number of Chinese on the Ballarat diggings almost doubled - from 5,000 in 1856 to 9,000 in 1858.

Chow Chow (Chinamen on Ballarat) by Charles Doudiet, 1854. Watercolour reproduced courtesy Art Gallery of Ballarat

This petition from Chinese diggers also protested the 1855 immigration tax. This petition includes 3089 Chinese signatures.

Courtesy Public Record Office Victoria

Anna Kyi examines petitions of Chinese residents in these two articles in Provenance Number 8 September 2009: ‘Finding the Chinese perspective: Locating Chinese petitions against anti-Chinese legislation during the mid to late 1850s’ and ‘The most determined, sustained diggers’ resistance campaign: Chinese protests against the Victorian Government’s anti-Chinese legislation, 1855 to 1862’.

Provenance is a free journal published online by Public Record Office Victoria.

Author: Ann Wilcox