Beatrice Phillips (1878-1945) had an impressive record of criminal convictions. From a first offence in 1896, we estimate that she was convicted no less than 227 times over the following 47 years. And there may well have been more. Her prison record sheets were so crammed with listed offences that it was very difficult to count them! Of course unless the offences resulted in a prison term, convictions would not appear on her record sheet at all, and we found reference to other offences reported in the newspapers that reflect that. Although we don’t know this for certain, it is quite possible that she was the most-convicted woman in Victoria.[i]

Almost all of Beatrice’s offences related to poverty – vagrancy, having no lawful means of support – but she was also convicted of drunkenness, using obscene language, damaging property and theft. These offences were by far the most common committed by women at this time, although few were quite such persistent offenders as Beatrice!

Embarking on a life of crime

The details of Beatrice’s first encounter with the law are confusing. The first page of her prison record (there were five subsequent pages) records a conviction for using obscene language on 4 May 1896 in Richmond. She was fined, with a two-month term of imprisonment in default. The same note mentions ‘and 10 others under one month’, although whether they came before or after the May 1896 conviction is not clear. None of these convictions was reported in the press. Within two years however, Beatrice had acquired enough of a reputation for her convictions to merit the attention of the ‘Police News’ sections of the newspapers. On 13 August 1898 for example, she was charged with ‘offensive behaviour’, although the description of the offence suggests more high spirits and drunkenness than anything more sinister. Constable Hall disagreed. He told the court that:

about 2 o’clock on Sunday morning accused was misbehaving herself at a coffee stall in City road. She was pulling a young man about and dancing on the footpath. When witness spoke to her she caught him round the neck and tried to kiss him. A fine of 20/- was imposed, in default seven days’ imprisonment. (The Record, 13 August 1898, p. 4)

Clearly it didn’t pay to try to kiss a policeman on duty!

In December 1898 Beatrice was again in trouble and this time she was described as a ‘young woman with a bad record’. She was found by Constable McIntyre at about 1 AM:

sitting on a doorstep in Park street [South Melbourne] and upon being requested to go home replied with a volley of abusive and filthy language. For this she was fined 5/-, in default 12 hours’ imprisonment. (Argus, 28 December 1898, p. 5)

Sadly for Beatrice, her spell in the cells allowed the police to realise that there was a warrant out for her arrest for breaking and entering and stealing kitchen utensils valued at 12/-. The police did the rounds of the second-hand shops, recovered most of the stolen property, and promptly charged Beatrice with the offence. Back to court she went.

A precarious living

Women like Beatrice lived precarious lives, prey to exploitation and abuse. But occasionally the tables were turned – somewhat. This proved to be the case when Beatrice appeared in court on the theft charge in January 1899. Her accuser was one Frantz Fredericson, who claimed to have seen Beatrice in City road the previous evening. Fredericson maintained that he had refused her ‘solicitation’ for a drink, ‘whereupon she threatened to make it warm for him’. However it transpired that the ‘truth’ of the matter lay elsewhere. A sharp-eyed, elderly neighbour then gave evidence, confirming that she had indeed seen Beatrice break a window, enter the property and leave some time later with a parcel. However she also said that she had seen Beatrice enter the property with Fredericson at about 11 o’clock the previous evening and that ‘she was kicked out by him when he went to work’. Quite a different story! Beatrice immediately confirmed this account:

That’s right, that’s the truth your worship! He got all he could out of me and put me outside without a penny. That was why I took the things away from that place.

Police Magistrate Mr Keogh was unimpressed. ’That will do’, he was reported as saying. ‘You are imprisoned till the rising of the court.’ It was a victory of sorts. By all accounts the elderly witness relished her moment in the lime-light, the prosecution was discomfited, no conviction was recorded, and the courtroom was highly entertained.

Imprisoned ‘For Her Country’s Good’

Beatrice’s escape from prison was to be short-lived. In the following week she was brought before the court in South Melbourne once again, this time charged with having no visible, lawful means of support. The Record reported the matter under the heading ‘FOR HER COUNTRY’S GOOD’.

Inspector Crampton said that the accused was in the habit of roaming about at all hours of the day and night, and for her own good as well as those enticed by her, it would be advisable to put her out of harm’s way for a time. She was sent to gaol for three months. (The Record, 14 January 1899, p. 4.)

This conviction was recorded in her prison register.

‘A Disreputable Den’

When not in prison, women like Beatrice lived a hand-to-mouth existence in conditions of desperate poverty. Along with others she tried to earn enough to survive by soliciting in the gardens (the Carlton and Fitzroy gardens were common haunts), but this was dangerous work, and Beatrice seems to have drunk most of the proceeds away. If there was anywhere she could call home, it was probably a room in premises like that in Blakeney Place South Melbourne, described by the police in January 1901 as a ‘disreputable den’ and a ‘house of bad repute’. It was from this address that she was arrested yet again for vagrancy and sentenced to six months’ imprisonment. The police gave her ‘a very bad character’ and described her as ‘a thorough nuisance’. Apparently that was enough! While a young man arrested with her was discharged with only a caution, the owner of the property was charged with ‘keeping a house frequented by idle and disorderly persons’, and sentenced to one month’s imprisonment. The property itself was described as a ‘filthy den, destitute of all furniture, with only some rags by way of bedding.’

‘An Undesirable Character’

According to the Record, Beatrice already had some 38 prior convictions by the time she appeared yet again in the South Melbourne Police Court in August 1902. She was aged about 24 and was charged with ‘being an undesirable character.’ What this meant precisely is unclear, but the press account noted that the arresting police ‘gave the accused a bad character, stating that she was constantly on the City road at night accosting men. She did no work and was a perfect nuisance about the place’. When asked to explain herself, Beatrice allegedly responded: ’it is all drink’. She was fined five shillings, with one month’s imprisonment in default, but it seems that on this occasion she may have managed to pay the fine, since no related prison term appears on her record.

‘The Worst Woman in Melbourne’

Nothing improved for Beatrice over the next two years and in October 1904 the Geelong Advertiser amused itself at her expense by describing her as ‘the worst woman in Melbourne’, after a play then running in the theatre. The charge that gave rise to this title was similar to her other offences – vagrancy, this time compounded by criminal damage (smashing the window of the cab conveying her to the watch house). Beatrice apparently ‘made an earnest appeal for mercy’, but the Bench was unmoved, committing her to prison for 12 months, with additional fines for the vagrancy and damage.

A new City Watch House - first prisoner

On 1 September 1909 a brand new City Watch House opened in Russell Street in the city. The police were very proud of their new facility and opened it up for public inspection on the opening day. For most of the day it was empty of occupants, but then in the evening the first prisoner was arrested. It was none other than Beatrice! On this occasion she was charged with using obscene language, but according to a lengthy report in the Age, that was just the beginning! Beatrice was obviously well-known to the Age correspondent, who described her as 'an excitable woman at any time', but who 'was positively explosive last night'. He went on to describe her antics as the hapless police tried to arrest her, to the amusement of a watching crowd of onlookers.

Beatrice had evidently been swearing loudly and profusely in Russell Street, when she attracted the attention of Sergeant Satchwell. His suggestion that she moderate her language met with a stream of personal abuse, at which the sergeant hailed a cab to take her to the watch house. As he tried to drag her out of the cab and onto the watch house steps, Beatrice succeeded in tripping him up and rolling him in the gutter. Sergeant Satchwell managed to right himself and began to try to force Beatrice up the steps to the entrance, whereupon she tripped him up again. Two constables had to come to his aid to get her inside, while the crowd enjoyed the show.

Once inside the new facility, a newly-appointed matron came forward to search Beatrice, in line with a new procedure for searching women prisoners - in vain. As the correspondent noted in amusement: 'All she [the matron] could do was circulate around the edges of a disturbance that looked like a whirlwind and made a noise like a thunder storm.' In the end both constables and the sergeant were required to hold Beatrice down while the matron performed her search. Meanwhile Beatrice went on yelling. She was calmed eventually when she was joined in the cell by another prisoner, charged with damaging property. This woman was possessed of a 'really fine contralto voice' and she 'sang Beatrice to rest with Killarney'. Peace descended at last on the watch house.

All in all it was not the most auspicious beginning for the new watch house, as the Age noted. Their headline read: 'THE NEW CITY WATCH HOUSE/ OPENED IN TRIBULATION.' It was not the best day for Beatrice either. Since the next day was a public holiday, she was held in the cells again overnight to appear in court the following day. The outcome of this appearance is not recorded.

A lifetime behind bars

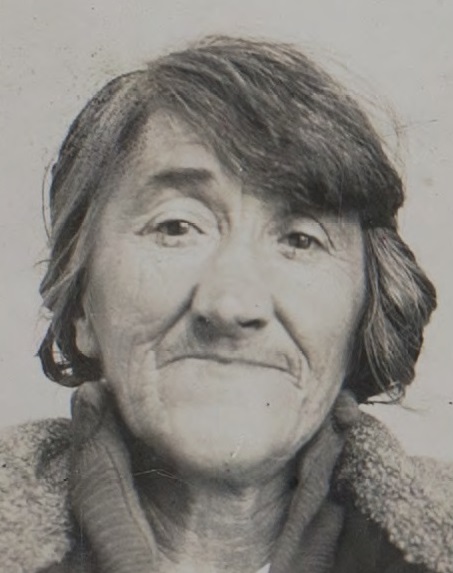

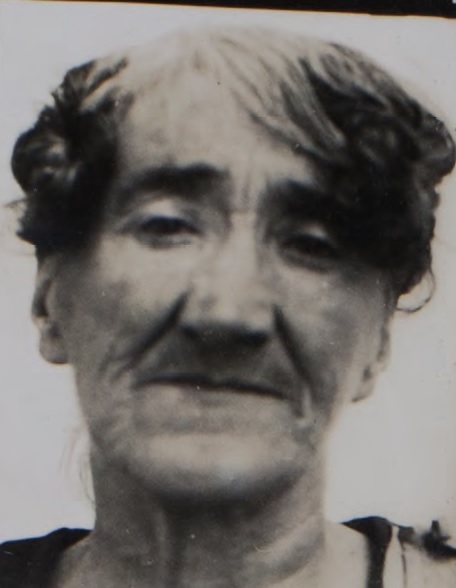

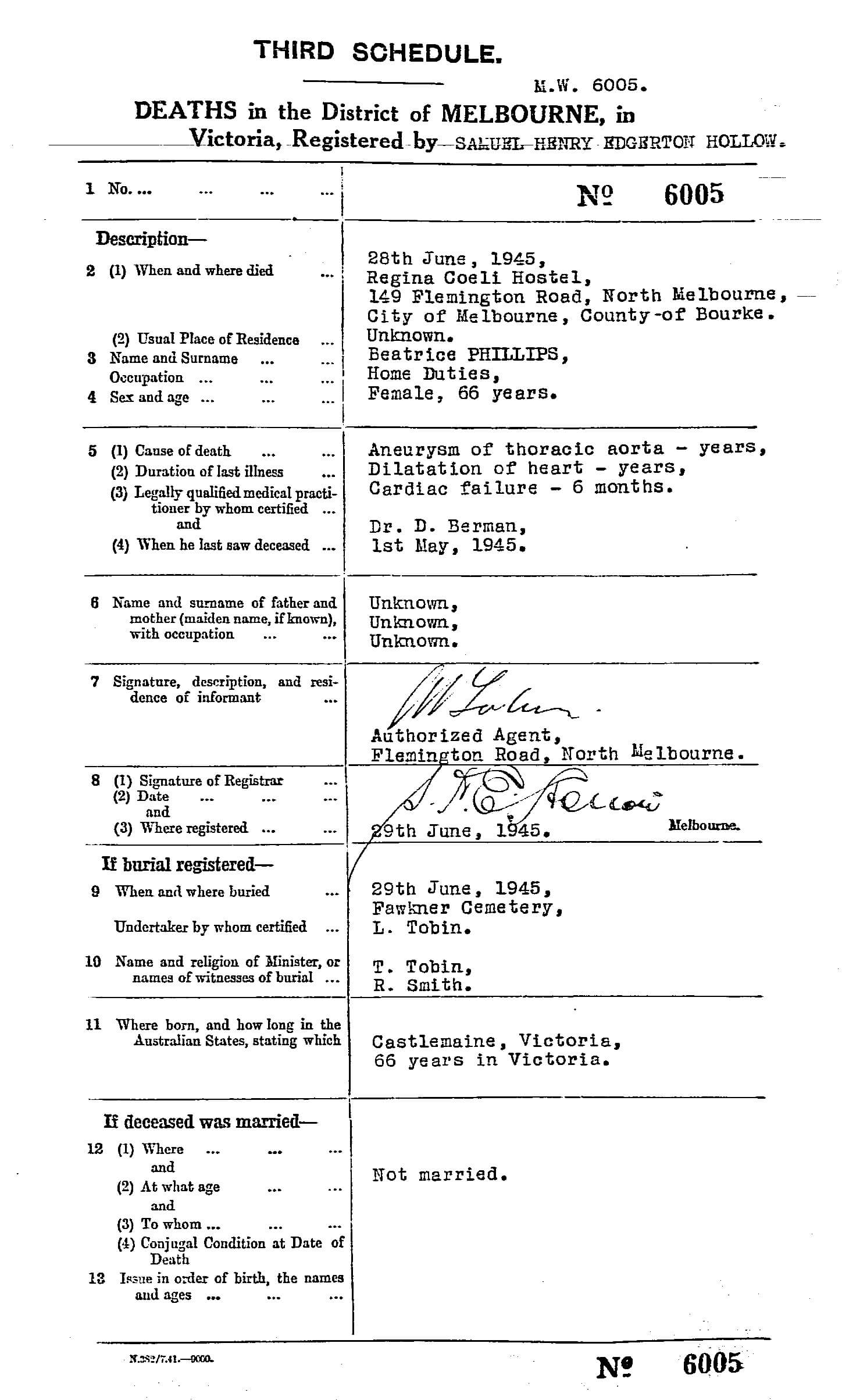

This was to be the pattern of Beatrice’s life for the next forty years. She would serve a stint in prison, have a brief interlude of ‘freedom’, then commit another offence and return to prison. At intervals the authorities evidently tried a little rehabilitation for Beatrice. At the end of August 1910 for example she was sent to 'Jika Reformatory Prison' for several years. On her release in April 1913 her prison sheet records that she was 'handed over to [the] Sisters of Mercy, Oakleigh Convent', although we have not yet confirmed how long she remained in the convent, or what she did while she was there. But by 1915 her regular stints in prison had resumed. Later in Beatrice's life she was rarely free for more than a week or two at a time and the prison photographs reveal an increasingly ravaged appearance, no doubt reflecting the effects of drink and hard living. On one occasion she seems to have been detained after drinking methylated spirits. By then prison might have been Beatrice's only refuge. She was probably unemployable, did not qualify for a pension, and her opportunities for soliciting were long gone. Prison may have been her only option for a bed and a meal. Her last recorded conviction was in June 1944 and she died of heart failure in June 1945 at the Regina Coell Hostel on Flemington Road. Her age at death was recorded as 66 years - a surprisingly long life in the circumstances.

Further reading

Graeme Davison, David Dunstan & Chris McConville (eds) The Outcasts of Melbourne: Essays in Social History. Sydney, Allen & Unwin, 1985.

Raelene Francis Selling Sex: a hidden history of prostitution Sydney, University of NSW Press, 2007.

John Stanley James The Vagabond Papers (expanded edition). Ed. Michael Cannon. Melbourne, Monash University Publishing, 2016. First published in 5 vols in 1877-78. Abridged edition Melbourne University Press, 1969.

Alana Piper & Victoria Nagy, ‘Versatile Offending: Criminal careers of Female Prisoners in Australia, 1860-1920’, Journal of Interdisciplinary History, Vol. XLVIII, No. 2, Autumn 2017, pp. 187-2010.

[i] In a study of female offenders in Australia Alana Piper and Victoria Nagy identified Elizabeth Turnbull as the most-convicted woman in their study, with 188 convictions between 1910 and 1947. ‘Versatile Offending: Criminal Careers of Female Prisoners in Australia, 1860-1920’, Journal of Interdisciplinary History, Vol XLVIII, No. 2, Autumn 2017, p. 200.

[ii] ‘Phillips, Beatrice, No. 6656. PROV VPRS 516/P2, unit 12. Her later offences were recorded as record 7565