Martha Needle (1864-1894) was one of Australia’s worst female killers. In 1894 she was hanged for the murder of her fiancé’s brother, Louis Juncken. But before that she probably poisoned both her former husband and all three of her children.

Early life

Martha Needle was born on 9 April 1864 near the small rural town of Morgan in South Australia. Her parents Joseph Henry Charles and Mary Charles separated seven months before Martha was born and when Martha was two, her mother remarried – ‘another brutish man – 39-year-old Daniel Foran’.

Police reports suggest an impoverished, unhappy childhood, marred by violence and abuse. Martha’s mother was an alcoholic who had ‘convictions for drunkenness, indecent language and wilful damage’. One of Martha’s neighbours later gave evidence that her mother ‘used to beat her pretty severely at times… I have seen her hit her with a stick, and she told me her mother used to tie her up and hit her with a rope.’

Martha’s stepfather was worse. In 1876, he was gaoled for sexually assaulting Martha, aged only 11:

Daniel Foran, who was charged with indecently assaulting his stepdaughter, Martha Charles at Adelaide in December, 1875, and found guilty was next brought up for sentence. His honour alluded to the enormity of the crime of which the prisoner had been found guilty, and sentenced him to the full term allowed by the Act, viz., two years with hard labour. (South Australian Advertiser, 4 April 1876)

Marriage

At the age of 17 Martha married Henry Needle, a ‘short, strong-built’ carpenter, five years older than her. The couple moved to Sydney so that Henry could find work and it was here that their first child, Mabel Hannah was born, on 13 November 1882.

On 6 October 1884, Martha’s second child, Elsie, was born and around 1885, the couple left for Melbourne and settled in Richmond. Henry had a good income and the couple was described by neighbours as ‘comfortably situated and well-matched’. (Argus, 15 June 1894).

Tragedy

Towards the end of 1885, their eldest daughter Mabel got sick, suffering from fever, vomiting and spasms of the stomach. She died on 28 December 1885: Martha stated that she simply ‘seemed to fade’. There was no suspicion surrounding her death. The doctor, Frederick Elsner, certified that the three-year-old had died from ‘cerebral tumour (congenital) and respiratory and cardiac bronchitis’.

After Mabel’s death, the pleasures of marriage palled. Henry could not find work locally and had to travel to Sydney, where he would stay for several months. A newspaper later reported that Martha began to go out at night alone – and that she had become renowned locally for having ‘a flighty disposition fond of company, and with a weakness for the admiration of the sterner sex, which was invariably accorded to her’. The birth of their third child May in 1886 did little to improve their marriage. Henry became increasingly jealous and morose.

In 1889, Henry suddenly fell ill. His doctor, George Hodgson, recalled that Henry had been a robust man but was now suffering from acute vomiting. His behaviour was also noted as odd. On one visit the doctor observed that Henry had left untouched some chicken broth and jelly that Martha had served him.

Henry died on 4 October 1889, with Martha by his side. The official cause of death was ‘sub-acute hepatitis, persistent vomiting, enteric fever, and exhaustion, due to obstinacy in not taking nourishment’. Despite the mysterious nature and sudden onset of the illness, no post mortem was performed. No suspicion attached to Martha who seemed to give him devoted care.

About a year after Henry’s death, six-year-old Elsie began to fall ill. In the courtroom later her doctor [vaguely] recalled that he thought Elsie was suffering from measles; but he remembered the young child had been vomiting. The one clear memory that the doctor had was of Elsie’s ‘appealing’ mother. He told the courtroom that Martha had never appeared ‘inattentive or unkind’; nor had she ever obstructed his attendance. Elsie suffered for almost 2 months, passing away on the 9th December 1890.

When Elsie was ill I visited frequently. The prisoner’s manner towards the child could not have been more kind and attentive… When Elsie died I saw the accused the same night. She was greatly distressed over it. (Evidence of Otto Juncken, The Queen v Martha Needle, 1894)

Only seven months after the death of her older sister, four-year-old May’s health also deteriorated. The previously healthy child began to display peculiar and worrying symptoms, the most notable was constant vomiting. The little girl died on 27 August 1891. Her death certificate listed ‘Tubercular Meningitis’ as the cause, but her doctor later testified: ‘The case attracted my attention particularly. I was always puzzled by the case. I could not arrive at a diagnosis satisfactory to myself’. Martha Needle’s care of her daughter was not questioned – in fact, she was praised:

Mrs Needle’s conduct towards May could not have been more kind than it was. She seemed to have all a motherly love and affection for her. I saw her after the child was dead. She was greatly distressed over it. (Evidence of Otto Juncken, The Queen v Martha Needle, 1894)

A new start

After May’s death Martha moved to Richmond to keep house for Otto and Louis Juncken. She and Otto soon became engaged, but during this time Martha’s behaviour began to cause concern. She would become unresponsive or rigid for long periods: on at least one occasion she went out to ‘search for’ her dead children. Not surprisingly Louis became concerned and opposed the engagement.

The crime

On 25 April 1894 Louis fell ill with strange symptoms - vomiting, a sore mouth and gums, a sore tongue. He died on 15 May.

I remember Louis getting ill… He suffered from vomiting and sore mouth and tongue and sore gums. Mrs Needle was attending him and myself. She prepared the food and gave the medicine. (Evidence presented by Otto Juncken, The Queen v Martha Needle, 1894)

Barely one month later Otto’s remaining brother Herman also fell ill. Puzzled by Herman’s symptoms, his doctor arranged for analysis of the vomit. It revealed arsenic coloured by charcoal – similar to the constituents of a popular rat poison, ‘Rough on Rats’. The doctor called the police.

Caught in the act!

After Herman’s recovery the police set a trap. Police hid outside the Juncken house as Herman went in to tea. Within minutes Martha was caught ‘in the very act of offering a cup of tea containing 10 grains of arsenic.’ A box of Rough on Rats was found in the cupboard.

Louis’ body was quickly exhumed and found to contain 3.4 grains of arsenic. Two grains were enough to kill. Police also exhumed the bodies of Henry Needle, Elsie and May Needle children. All contained traces of arsenic.

The trial

Martha was tried in September 1894 on a charge of murdering Louis Juncken. In her defence her counsel attempted to argue that Martha’s long periods of ‘unconsciousness’ meant that she was not responsible for her actions. The murder of her children seemed especially inconsistent with her apparent behaviour as a fond mother.

I noticed she was subject to fits or faints. They would occur any time…. The fits came without warning. She would fall suddenly right down as if she were struck. She would be quite unconscious… (Evidence of Otto Juncken, The Queen v Martha Needle, 1894)

But doctors called to give evidence were reluctant to commit themselves and Justice Hodges rejected the plea of insanity, observing: ‘the law cannot wait while philosophers, physicians and scientists settle metaphysical problems. …Justice must be swift and sure’.

The final chapter

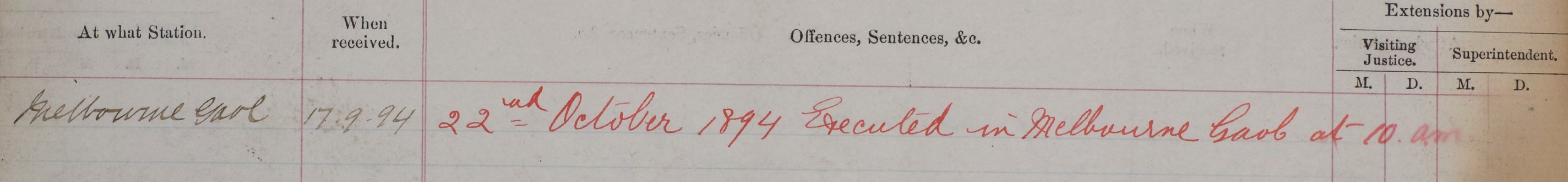

The jury found Martha Needle guilty and gave no recommendation to mercy. She was hanged at Melbourne Gaol on 22 October 1894, leaving all her belongings to Otto, who supported her to the end.

Mad, or bad?

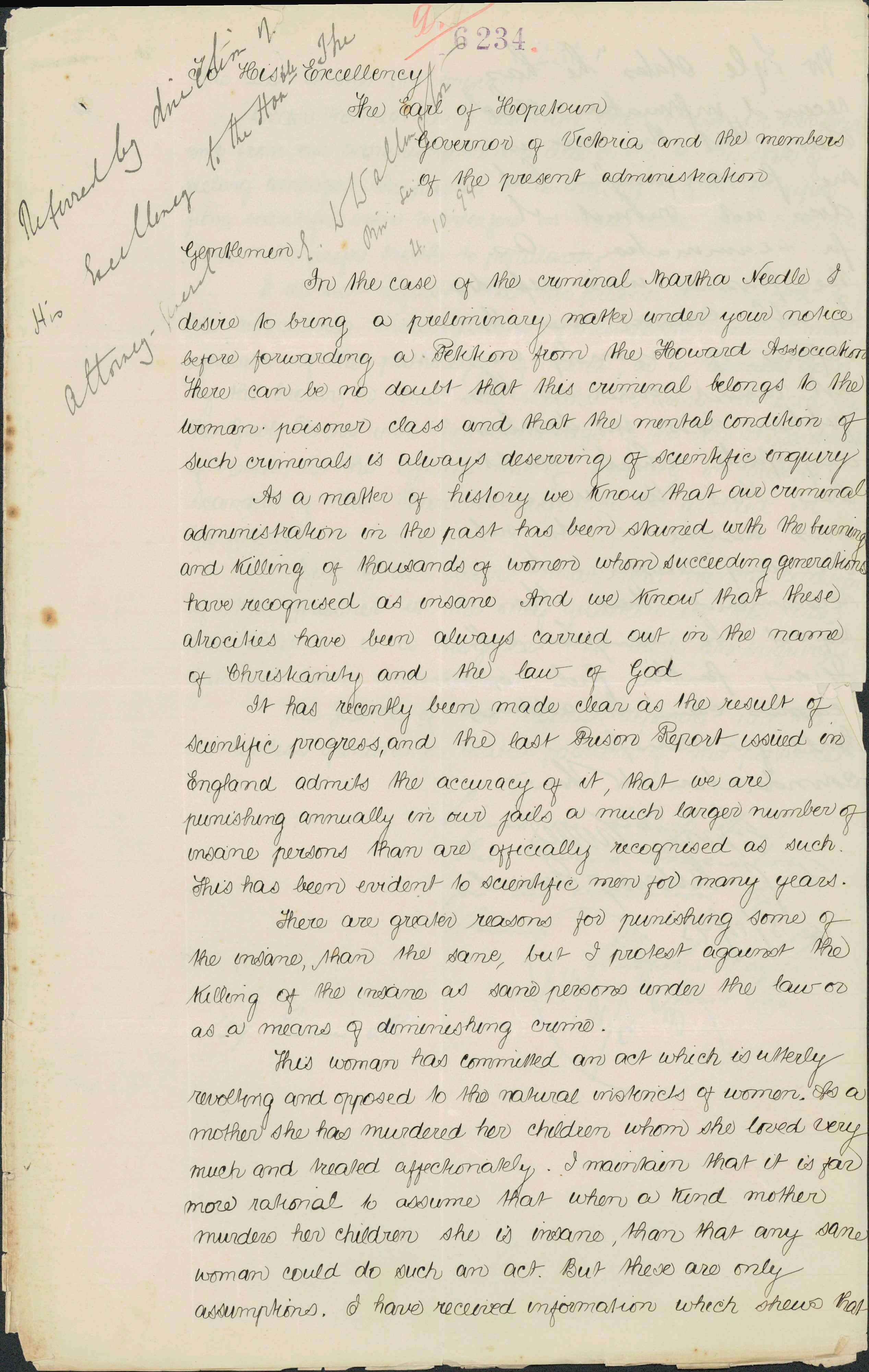

A few days after Martha’s trial had ended, lawyer Marshall Lyle wrote to the Governor, the Earl of Hopetoun, on behalf of the Victorian branch of the Howard Association for the Prevention of Crime.

Lyle conceded Needle had committed acts ‘utterly revolting and opposed to the natural instincts of women. She had murdered children ‘whom she loved very much and treated affectionately.’ But he argued it was only ‘rational to assume that when a kind mother murders her children, she is insane.’

Lyle claimed that ‘criminal administration in the past has been stained with the burning and killing of thousands of women whom succeeding generations have recognised as insane.’ Even in Victoria ‘we are punishing annually in our gaols a much larger number of insane persons than are officially recognised as such.’

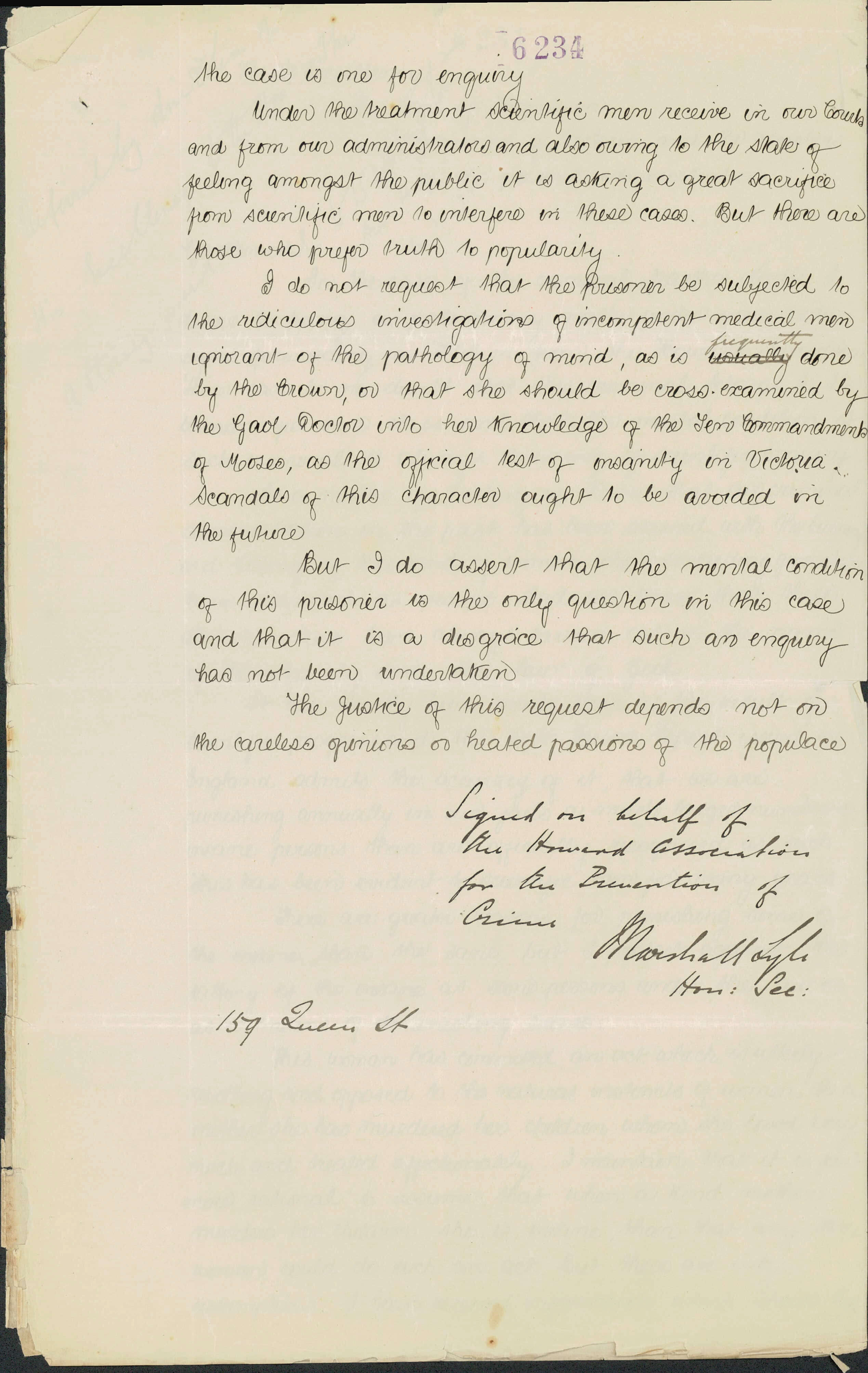

Lyle advocated for proper scientific inquiry of Needle’s case, rather than the Crown’s use of ‘incompetent medical men’. He questioned the gaol doctor’s test of Needle’s sanity which consisted of ‘a cross-examination into her knowledge of the Ten Commandments of Moses’. ‘Scandals of this character ought to be avoided in future’, he warned.

Lord Hopetoun referred the letter to the Government. Attorney-General Isaac Isaacs replied: ‘As the prisoner was defended by able counsel… and as this petition does not disclose any facts which would shew [sic] that the woman was insane, I do not see any reason to recommend that the request be complied with’.

Petition reproduced courtesy Public Record Office Victoria