In December 1898 Melbourne was transfixed by a gruesome mystery. The body of a young woman was found in the Yarra River at Richmond, her naked body jammed into a boot box. No one came forward to claim her. For nearly a month the police sought desperately to identify her, while thousands of Melburnians filed past her body in the morgue. Finally she was identified as seventeen-year-old Mabel Ambrose, the tragic victim of an abortion gone wrong. She was one of many young women who died after abortions at this time, although most did not excite such an extraordinary degree of interest. Olga Radalyski and Travice Tod were charged with her murder.

Mabel Ambrose’s story

Mabel Ambrose was a 17 year-old seamstress and domestic servant from South Yarra. In 1898 she lived with her widowed mother and two other children in a poor household, often dependant on charity. Mrs Ambrose was the widow of a telegraph operator and the family had lived in the country near Lang Lang until Mabel’s father fell ill with typhoid fever and died in the Melbourne Hospital. The family then moved to South Yarra. It was claimed that Mabel was apprenticed as a dressmaker, but the court proceedings suggest that she was actually employed as a domestic servant in the year before her death.

Apparently Mabel liked a good time and had been warned by the local South Yarra police constables about forming ‘bad habits and associations’. There was some inference in court evidence that Mrs Ambrose (whose real name was Mary Ann Disccatia) drank consistently and that she could not control Mabel, who had stayed out all night on several occasions. The two younger Ambrose children were subsequently removed from their mother’s care and committed to the industrial schools. (Age, 31 January 1899, p. 5)

In 1898 Mabel began seeing a local real estate agent Travice Tod. Tod collected the rent from Mabel’s mother and according to Mrs Ambrose, ‘when he called they would talk and laugh together for a couple of hours.’ (Age, 26 January 1899, p. 5) Mabel’s mother liked Tod and may have harboured hopes for her daughter’s future. In her evidence at the inquest Thekla Dubberke also claimed that Mabel had told her that Tod had offered marriage. But Travice Tod had no intention of marrying Mabel. He was already engaged to a girl in the country and the wedding was not far off. When Mabel found herself pregnant, Tod took her to see Madame Olga Radalyski, to help her ‘get rid of her trouble’.

Olga Radalysiki’s story

Madame Olga Radalyski was the working name of one Elizabeth Elburn. She was actually a publican’s daughter from Essendon, but liked to pass herself off as a Russian, presumably to add an exotic note to her business as a ‘futurist’ or ‘palmist’ (a reader of palms) and masseuse. There was great interest in all of these minor off-shoots of the occult at this time. In 1898 Radalyski was living in South Yarra in a house she shared with another woman, Thekla Dubberke, (aka Beatrice Jamieson or Vera Orloff). Olga was by then separated from her husband. The house may have doubled as a brothel on occasions, but Radalyski also offered certain ‘medical electric treatments’, probably designed to procure miscarriages. Dubberke’s occupation was never stated. Although she seems to have acted as a sort of assistant to Radalyski, she also paid half of the rent on the house. She was apparently maintained by at least one ‘gentleman’ at this time, but also had a relationship with a Collins Street doctor – Dr William Gaze. The nature of their relationship was never made clear, but the implication was that it was a casual sexual relationship. Tod also collected the rent from Olga Radalyski and was said to have given her a reduced rental, although the reason for the reduction was not made clear. Olga apparently agreed to help Mabel ‘for his [Tod’s] sake’.

Home remedies and backyard abortions

By the 1890s it was possible for a doctor to perform a curette to remove an early pregnancy with relative safety, but it was illegal to do so. A doctor who performed such an operation faced a serious charge of ‘malpractice’. The actual charge was ‘performing an illegal operation.’ Nevertheless it is fairly clear that such operations were performed, for wealthy patients in private clinics, or for needy girls by certain doctors in their rooms clandestinely. Thekla Dubberke admitted to one such procedure. But of course such operations were expensive, since the doctors risked prosecution. Even so-called back-yard abortionists usually charged a sizeable fee – two guineas (£2/2s) was a common charge, which was a large amount for a poor serving girl to find. Not surprisingly, many tried so-called ‘home remedies’ first. These included taking large doses of one of the many purgative medicines sold by chemists, or making up a concoction at home. Many patent medicines sold at this time advertised their effectiveness in treating a range of ailments, including ‘female irregularity’ – a euphemism for pregnancy. They rarely worked. Parsley tea was said to be effective, if consumed in large enough quantities. Others resorted to scalding hot baths, jumping off tables and other such remedies – usually without success.

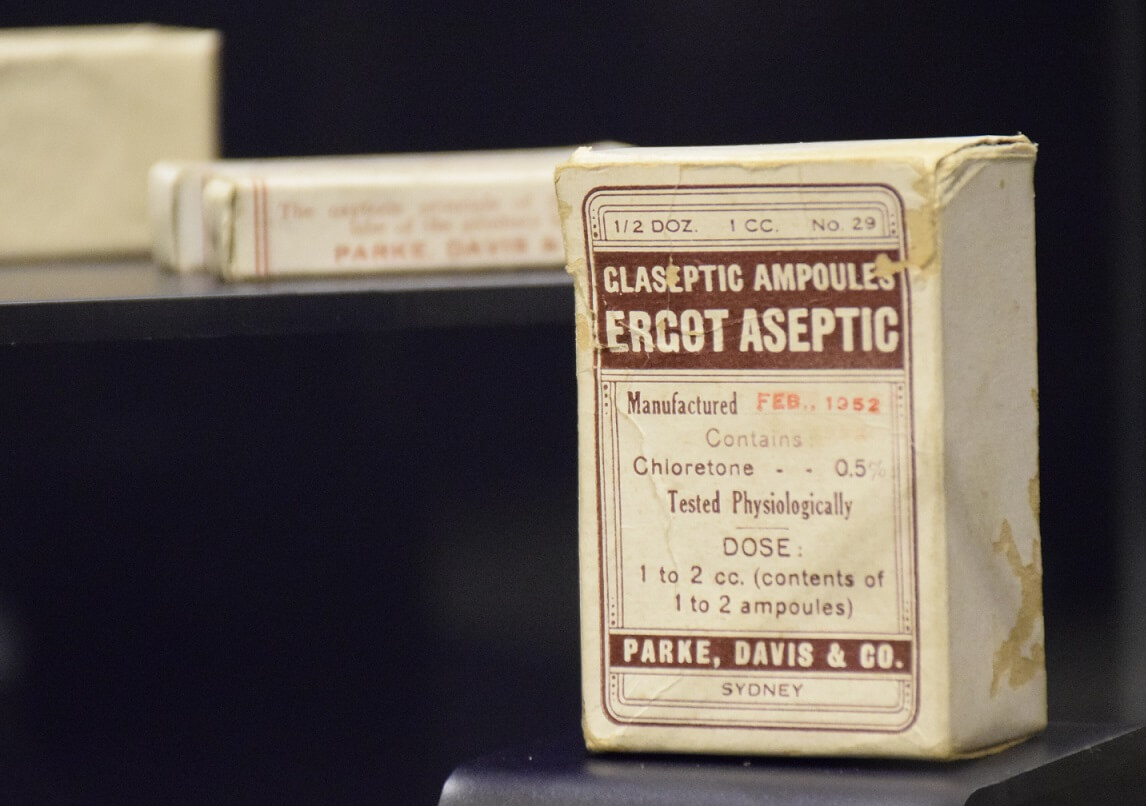

One substance that was known to have an effect was ergot – made from a fungus that grew naturally on rye. It had a legitimate use in the management of childbirth to strengthen contractions, and was used for this purpose by doctors, but it was also known for its use as an abortifacient. Tod managed to convince a friend, who worked in a shop that sold patent medicines, to purchase a preparation that might have been ergot for him. After refusing initially, he eventually complied, but it did not work on Mabel. Thekla Dubberke also said that she bought some ergot from the dispensing chemist at the Alfred Hospital, (Horsham Times, 27 January 1899, p.2) although the dispenser denied having supplied her with anything (Age, 31 January 1899, p. 5). Mabel complained of pain after the administration of the ergot, but again it did not produce a miscarriage.

At that point Tod moved Mabel into Olga’s house so that she could use her ‘electric medicine’ on Mabel.

A ‘darling little battery’

Electric medicine was a new fad in the 1890s. Several quite legitimate physicians made use of it and public lectures were presented promoting its results. (An example appeared in the Leader, 26 November 1892, p. 44) However evidence presented at the inquest into Mabel’s death made it clear that Olga Radalyski employed what she called her ‘darling little battery’ for what was referred to in court as ‘illegal purposes’. It was later suggested that the ‘electric medicine’ was administered both externally and internally and that it was quite painful. Mabel was said to have cried during these ‘treatments’, but they did not kill her. Unfortunately they did not provoke a miscarriage either. At some point Radalyski tried to borrow an ‘instrument’ from Dr Gaze, but he refused to lend it to her, saying that it was far too dangerous. Mabel was also administered ‘enemas’ using ‘Condy’s fluid’ – a disinfectant made from potassium permanganate. That was equally ineffective. This all went on for several weeks, during which time Tod was a frequent visitor. At one point he apparently commented: ‘Poor girl: I couldn’t help having some regard for her.’ (Age, 26 January 1899, p. 5)

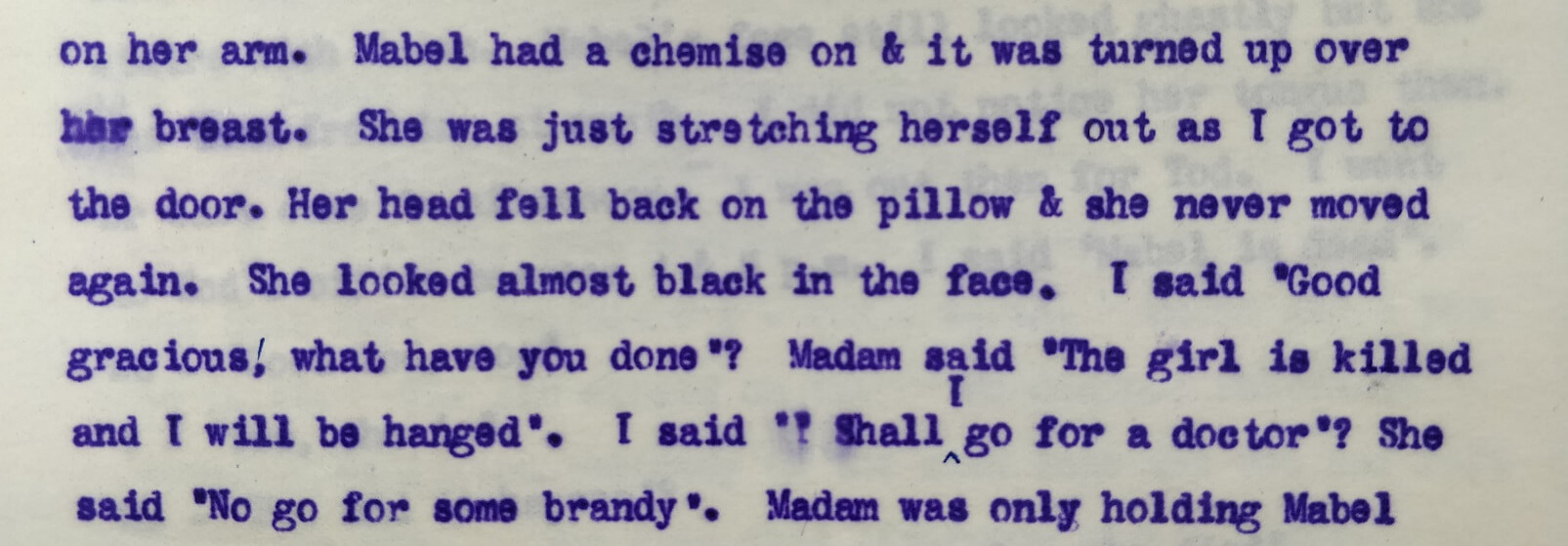

During or after the last particularly painful ‘treatment’ session Mabel apparently began to scream with the pain. Alarmed Olga placed a hand over her mouth to keep her quiet and smothered her – or that was the story presented to the court. The doctor who conducted the post mortem on Mabel’s body was unable to confirm this explanation, although he did confirm that she died from suffocation. There was also some speculation that she might have had some kind of fit. However, at that point panic erupted in the house.

Initial panic

The account of what happened next was given by Thekla Dubberke (Vera Orloff). Although she was not present in the room when Mabel died, she and Tod were instrumental in what followed. At first those in the house tried desperately to ‘revive’ Mabel. They tried to pour brandy down her throat as a stimulant, they rubbed brandy around her heart and then packed her body with hot water bottles to warm her up. Later in the day they persuaded Dr Gaze to come and see Mabel. He confirmed that she was dead, but refused to issue a medical certificate. According to a statement he made later, he advised them to report the death and arrange for burial.

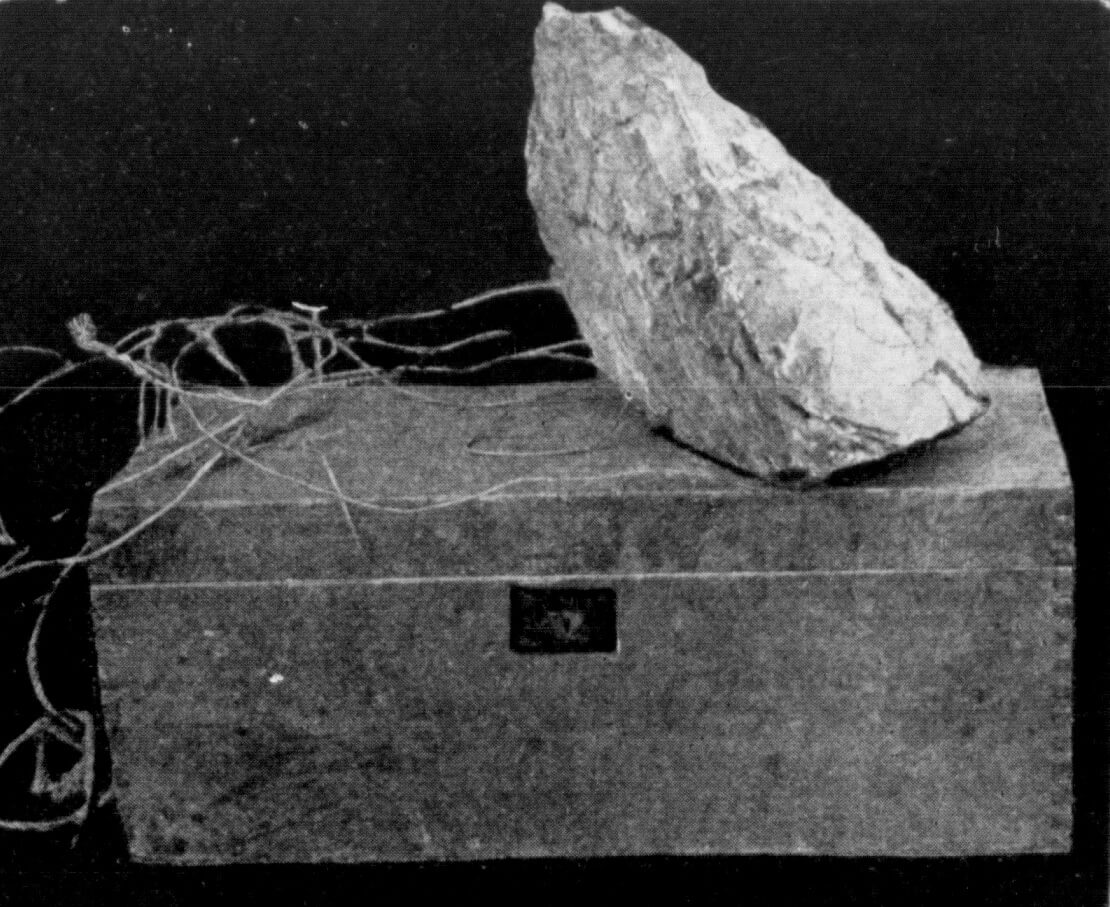

Of course they were afraid to do so. Madame apparently cried out ‘I have killed the girl and will be hanged’. Between them they decided to put the body in a sack and bury it ‘far away’. Tod brought a sack, and they packed Mabel’s body into it, but they decided to use a boot box instead. A ‘boot box’ was a wooden box, commonly used to store personal possessions, but of a size that would fit in the boot (back) of a buggy. There was some suggestion that Tod cut off a lock of Mabel’s hair as a keepsake, (a rather unlikely suggestion in the circumstances,) but it was also suggested that her hair was cut off to make her more difficult to identify. They debated whether to knock out a tooth for the same purpose. There was also speculation that they may have stamped on Mabel’s body to fit her into the box. Tod hired a buggy and he and Thekla took the box down to the Yarra, where they weighted it with a stone and pushed it into the river. By this time it was already decomposing and the smell was quite evident.

A gruesome discovery

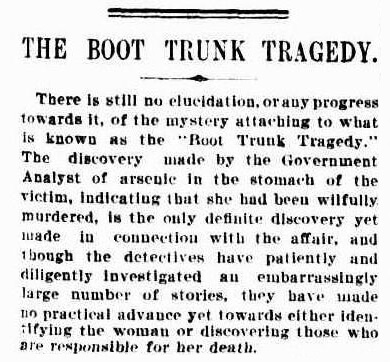

On 17 December three little boys playing near the river in Richmond, made a gruesome discovery. The box containing Mabel’s decomposing body was taken to the Morgue and enquiries began immediately in an attempt to identify her. What became known as the ‘Boot Trunk Tragedy’ (Age) or the ‘Yarra Mystery’ (Argus) was to dominate Melbourne’s newspaper reporting for the next month and more.

The Yarra Mystery

For weeks the police were mystified. No woman matching the body’s description had been reported missing and they had no clues to her identity. As was often done in these circumstances, the body was put on public display in the Morgue and people were invited to view it. Literally thousands did so. As the Age reported:

Seldom has an individual case in the criminal records of Melbourne created such general public interest as the crime which has become known as the Boot Trunk Tragedy. There was a record attendance at the Morgue yesterday, numbering over 1500 people. The total number of callers since the discovery of the woman’s body on 17th December has been over 5,000. No other case for many years past has given the detectives anything approaching the amount of work entailed in the present investigation. (Age, 10 January 1899, p. 5)

Some of these visitors were looking for missing relatives but most seem to have come on the off-chance that they might recognise the body. Or they came out of morbid curiosity. There was certainly less sensitivity around viewing dead bodies in the past. As the remains continued to decompose, police eventually buried the body, but preserved the head in alcohol and left it on display. Apparently Tod went to the Morgue to see it and told his friends that it didn’t resemble anyone he knew! In the meantime he told Mrs Ambrose that Mabel was alive and well, living in a ‘respectable house’ in South Yarra. Mrs Ambrose had been surprised and disappointed when Mabel did not come home for Christmas, but believed what ‘Mr Tod’ told her. This was a good short-term strategy for Tod, but risky in the long-term, as it indeed transpired.

Mabel identified

Eventually Mabel was identified when Constable Organ from the South Yarra Police visited the Morgue and noted certain similarities to Mabel. It transpired that he had been suspicious about her disappearance for some time. He visited her mother and persuaded her to view the head. Although Mabel’s features were much altered by decomposition and the preservation process, Mrs Ambrose at last realised that the mysterious body was that of her daughter. It was not long before the police came knocking on Tod’s door, and very soon after that Olga Radalyski and Thekla Dubberke were also arrested. Thekla very quickly told the police her full story. Both Tod and Radalyski were formally charged at the City Police Court on 12 January.

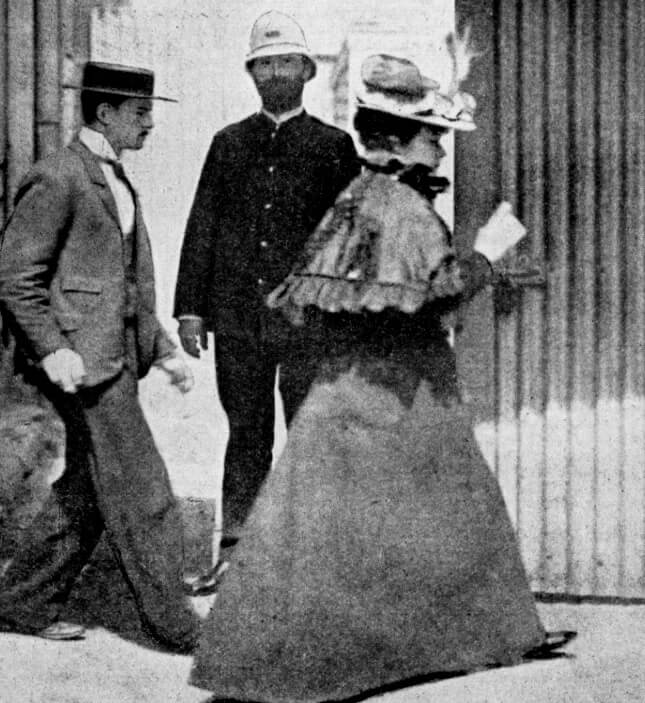

It was already clear by this time that Thekla Dubberke was likely to be the chief Crown witness and she left the court room before the other two were charged. The police reporter noted that ‘she had been standing at the door of the court, chatting with Detective Dungey in a very composed fashion’. The reporter added: ‘She is a good looking young woman, tall and of lady-like appearance, and did not seem to be much put about by her situation.’ Descriptions of the other defendants followed. Tod was described as ‘a slightly-built young man, of rather good appearance,’ and it was observed that he also ‘seemed fairly at his ease.’ Radalyski on the other hand, ‘looked older than 28, which she stated to be her age’. It was suggested that ever since Mabel’s death she had been haunted by the event and could not sleep. (Bendigo Independent, 13 January 1899, p. 2) The police sought an eight-day adjournment to prepare their evidence, which was granted.

The inquest

A preliminary inquest had been held just before Christmas, but was adjourned in the hopes that the body would be identified. It was resumed on 25 January. Given the intense interest in the case, the inquest proceedings were reported in great detail in all of the daily newspapers, and in many of the regional papers as well. The court was reported to be crowded with would-be spectators, but only those issued with tickets were allowed in. As anticipated both Radalyski and Tod were charged, while Dubberke, although technically still under arrest, was treated as the principal witness. Dr Gaze was also in court and after Dubberke gave her evidence was offered the opportunity to cross-examine her. He deferred his decision and the court adjourned for the day.

The inquest resumed on 30 January and there was some interest in the fact that in the interim Dr Gaze had appointed a legal counsel, Dr. McInerney. Under intense questioning Tod’s friend at the medicine shop also admitted that he had wondered about Mabel’s disappearance and had often asked Tod about it. On the day Tod was arrested he claimed to have viewed her head in the Morgue and recognised her, but was still making up his mind whether to speak to the police when they arrived to arrest Tod. There was some implication that several of Tod’s friends had suspicions that the body might be Mabel’s but had not said anything.

The inquest resumed for a third day on 1 February to consider the evidence of Dr James Neild who had performed the post mortem examination on Mabel’s body. In his evidence Dr Neild repeated his conclusion that Mabel had suffocated, but said that there was no evidence to suggest how that might have happened. Various other possible causes of death (including’ puerperal convulsions’ were debated and rejected. The doctor’s evidence was followed by the case summaries by both the Crown Prosecutor and the various defence lawyers. Tod’s defence barrister tried to suggest that Tod’s character had been considered unfairly. As the Age correspondent reported:

Tod had been accused of callousness, but he had acted with more concern for the girl’s welfare than 90 out of 100 cases of young men in a similar position, most of whom left the girl to get out of the trouble as best she could. (Age, 2 February 1899, p. 9.)

Sadly, his observation was probably accurate.

The inquest resumed for a fourth and final day on 2 February. In his address to the jury Radalyski’s defence lawyer tried to discredit the evidence presented by Thekla Dubberke in particular. His opinion was scathing: ‘As to the credibility of the girl Dubberke, would anyone jeopardise the liberty of a cat on the uncorroborated statements of such a person’, he asked the court. The defence of Dr Gaze suggested that he ‘had done nothing more than make an ass of himself, especially in connection with the girl Dubberke’.

The Coroner’s summing up made the nature of the crime before them clear to the jury. ‘the unlawful attempt at malpractice was felony’, he advised, ‘and when death was caused, even unintentionally, in the commission of a felony, the crime was murder’. It was a sobering reminder. The Coroner also seemed to share the general view of Thekla Dubberke:

They saw the class of girl Dubberke, the informant, was. She stood in the box and gave her evidence without a blush, disclosing the whole terrible history of her life in connection with these proceedings without seeming to feel the matter in the slightest degree. But all that the jury had to consider was whether she was a truthful witness.

Almost reluctantly it seems, the Coroner felt obliged to admit that ‘he had seen nothing that had shaken her credibility with regard to her testimony.’

The jury considered their verdict for some two hours before returning and finding all four participants, including Dr Gaze, guilty of murder. Radalyski was found guilty of committing the act, while Dubberke, Tod and Gaze were all found guilty of being ‘accessories before the fact’. They also commended the diligence of the police. (Age, 3 February 1899, p. 6)

The Trial

The trial took place at the Supreme Court before the Chief Justice on 22-24 February 1899. Once again a large crowd assembled outside the courthouse, but very few were able to secure admission. However in recognition of the degree of interest in the trial, the court had opened up the side galleries. Those who gained admission were said to include ‘a large number of ladies.’

In the end only Radalyski, Tod and the hapless Dr Gaze were charged, while Dubberke was discharged in exchange for her evidence. During Thekla’s cross-examination a strenuous effort was made to discredit her on moral grounds. Questions like ‘did you lead a proper life when at Mrs. Macdonald’s’, or observations like: ‘then you only went wrong in Osborne Street’, made the defence position clear. Dubberke appeared remarkably unfazed by the questions and admitted freely that she had been ‘kept’ by several gentlemen, whom she refused to name. She also refused to alter her account of the events surrounding Mabel’s death. (Age, 23 February 1899, p. 5) Similar comments were made about Mabel Ambrose on the second day of the trial. In response to the question from one of the defence counsel: ’What sort of a girl was Ambrose’, Robert Gabriel, Tod’s friend, replied: ‘Well, she was not a desirable companion for any respectable person’. The relevance of such a question was not challenged by either the Crown Prosecutor or the Chief Justice.

The verdict

The jury retired at 3.40 PM on the third day of the trial. From about 7 PM a large crowd began to gather outside the court awaiting the verdict, but it was not until 9.35 PM that the jury returned. They found both Olga Radalyski and Travice Tod guilty of murder, both ‘with a recommendation to mercy’. Dr Gaze was acquitted and immediately left the dock to join his brother. The jury recommendation reflected their view that there had been no intention to commit murder. However sentence of death was duly pronounced, as was required at law. Olga Radalyski immediately fainted and was carried from the courtroom. (Leader, 4 March 1899, p. 22.)

Some weeks later the full Cabinet met to consider the fates of Radalyski and Tod. They resolved to recommend to the Governor-in-Council that the death sentence be commuted to ten years’ imprisonment for Radalyski and six years for Tod. We feature the prison record of Olga Radalyski in the exhibition. Oddly, although her true name and identity was known, the prison register recorded her as ‘Olga Radalyski’ and entered her place of birth as ‘Russia’. It just goes to show that even such official documents can mislead!

Author: Margaret Anderson

Further reading:

Judith A. Allen Sex & Secrets: Crimes Involving Australian Women since 1880 Melbourne, Oxford University Press, 1990

Janet McCalman Sex and Suffering: Women’s Health and a Women’s Hospital Melbourne University Press, 1998.

Many thanks to Danielle Broadhurst for providing additional details.