Warning: This account includes references to sexual offences and sexual behaviour that some readers may find disturbing. Parental guidance is recommended.

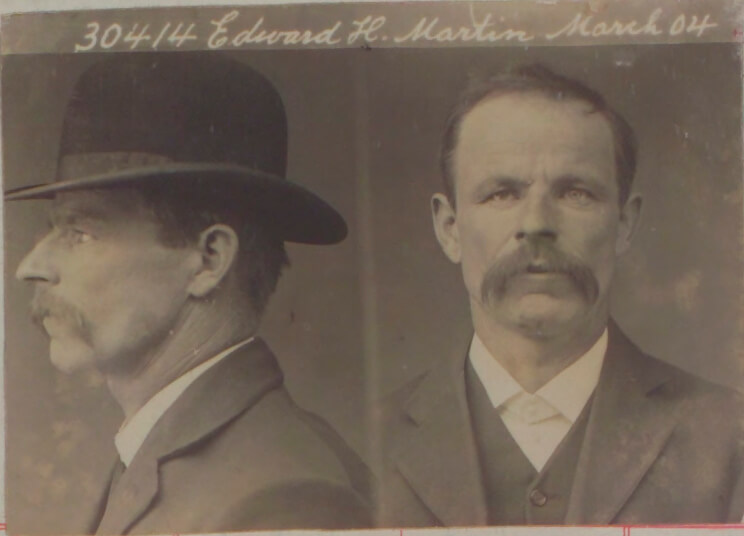

Sarah Lawton and Gertrude (known as Gertie) Bigwood were two little girls whose only real ‘crime’ was poverty. They were arrested in January 1904 in Bourke Street and subsequently appeared as witnesses in a carnal knowledge case. The case was proven and Edward Henry Martin was sentenced to three years with hard labour. But the two girls were also sentenced. Convicted of being ‘neglected children’ and judged to be leading ‘lives of depravity’, they were both sent to institutions. Sarah remained in the reformatory for seven years – more than twice the length of Martin’s sentence.

Alone and at risk in the city

On the afternoon of 12 January 1904 Sarah Lawton (aged 11) and Gertie Bigwood (aged 12), both from Collingwood, were in Bourke Street near the Parliament House steps. Sarah was begging, or ‘cadging’ as she called it, when she and Gertie were offered a shilling to ‘go with a man to his office’. From the evidence they gave it is unclear whether they actually intended to go to the office, but they were certainly following the man when Constable Crisfield of the Russell Street police station saw them ‘acting suspiciously’ and arrested them. The man was not pursued.

At the police station both girls gave evidence that implicated another man, Edward Henry Martin, a 35 year-old bootmaker from Collingwood, in criminal behaviour at his shop. Martin was arrested and taken to face the girls, who in the meantime had been placed with Miss Sutherland, a well-known provider of care for neglected children. The girls repeated their accusations directly to Martin in the presence of police, and Martin was subsequently charged with ‘carnally knowing a girl under the age of 16 years and over the age of ten years’. He was sent to trial at the Melbourne Supreme Court. The legal age of consent for girls at this time was 16 years, increased from 12 in 1891. Carnal knowledge of a child under ten years was still a capital offence in Victoria, while the offence on a child of Sarah and Gerties’ age carried a maximum penalty of 10 years’ imprisonment. (Crimes Act 1890 Vic, s. 45 & Crimes Act Amendment Act 1891, Vic s. 5)

The statements the girls provided to police made it clear that both had been approached by men for sex on repeated occasions. Like many children at this time, they were out and about in the city unsupervised, sometimes at all hours. Whether begging like Sarah, running messages, going to the shops, or working at one of the many jobs that employed children, there were many young people alone and at risk in the city of Melbourne well into the twentieth century. And clearly there were plenty of men waiting to prey on them. This is not a new phenomenon.

Neglected children

Constable Crisfield thought that the girls were ‘neglected children’ and they were duly charged with neglect before the City Court on 13 January 1904. In his evidence Detective-Sergeant Dungey claimed that: ‘the girls had made a statement which revealed a terrible state of depravity.’ While police enquiries were conducted, he asked the Bench to remand the girls to ‘the Schools’ for a fortnight. The girls allegedly ‘wept bitterly’ throughout the proceedings. Both mothers were in court. Initially Annie Lawton claimed that she had six children and had kept the second girl home to do some housework. She also claimed that Sarah had left school because she was 13. (Age, 14 January 1904, p. 9) However later evidence was presented to confirm Sarah’s actual age as 11. Mrs Bigwood claimed that she worked all day until ‘late at night and she thought her girl went to school.’ (Herald, 13 January 1904, p. 2) The Bench remanded both girls to the schools.

The trial

Martin’s trial took place in the Melbourne Supreme Court on 15 February 1904. Both girls were called to give evidence, as was Sarah’s mother.

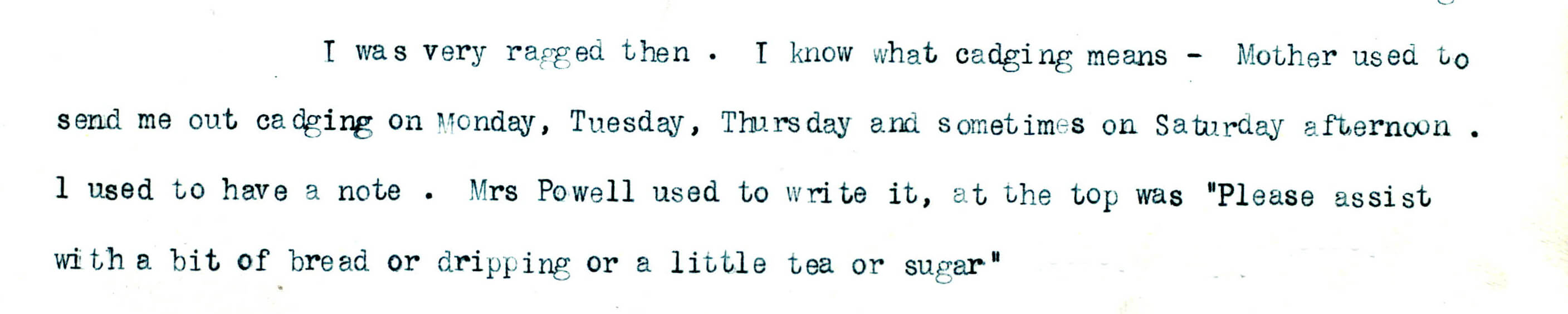

Each lived in severely impoverished circumstances. Sarah’s mother, Annie Maria Lawton, gave her address as 58 Rupert Street Collingwood, but it was obvious from Sarah’s account that the family had moved several times in the past year. Mrs Lawton described herself as a ‘married woman’, but said that her husband William had been away for five months and she had not heard from him for five weeks. She had six children to support. She could neither read nor write and admitted that she sometimes sent Sarah out begging. A sometime lodger in the house wrote begging notes for Sarah to carry.

Gertie gave her address as 54 Gipps Street Collingwood, where she lived with her widowed mother, a charwoman, who had three children at home.

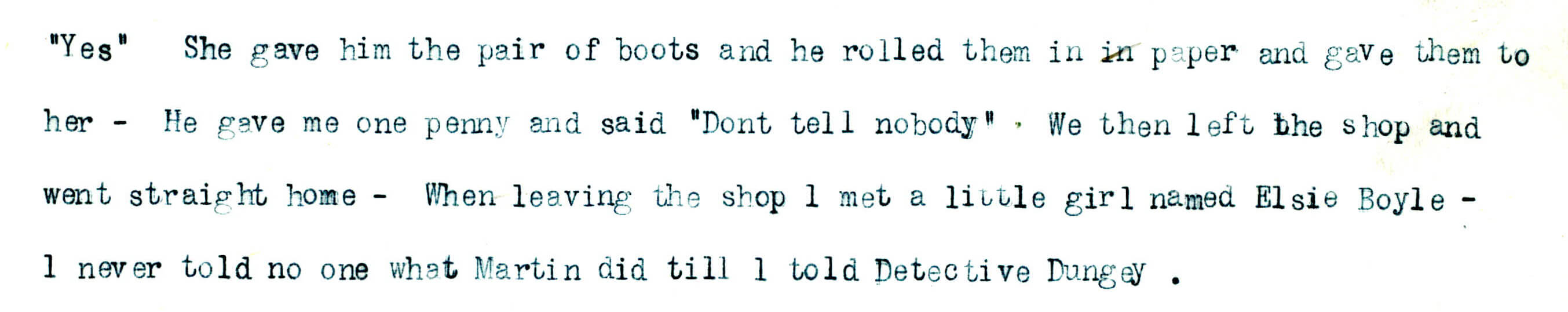

The evidence the girls gave was very matter-of-fact – disturbingly so in the view of both the Bench and the court reporters present. Although the versions of evidence printed in the newspapers were heavily censored, their disapproval was emblazoned in headlines like ‘SHOCKING DEPRAVITY’ and ‘JUVENILE DEPRAVITY’. Sarah told the court of her visit to Martin’s shoe shop some weeks before, in company with her little sister Violet, aged eight. Both girls were looking for old boots. After directing Violet to a pile of old boots in a corner of the shop, Martin offered Sarah a penny if she would come into the back room with him. The offence took place in the back room. Sarah told the court that she knew what Martin intended to do and that he was not the first. She went on to detail three other encounters -the first with ‘a boy’, and two others with men, one in a wood yard and one in a laneway at night. On both of those occasions she was offered a penny. She also told the court: ‘I did this sort of thing for the money. I did not get beaten if I didn’t bring the money home, I spent it on cakes and lollies.’ [sic.] (Trial brief the King vs Edward Henry Martin, transcript of evidence. PROV)

Under cross examination Sarah naively repeated her story about the man in Bourke Street: ‘I knew that for the shilling he was to do what Martin done, put his thing into mine. I was willing to do it for a penny.’ She also admitted that she was frightened and crying when she was arrested, because she thought she was going to gaol, and that as a consequence she might have said that ‘it was six or seven men that had done it to me’. However on the witness stand she suddenly remembered another instance – ‘an old man in Clifton Hill to whom I took the laundry – He felt me on the legs and privates and gave me a half penny to get a lolly.’

Statements like this suggest the ubiquity of sexual assaults on vulnerable children at this time.

The medical evidence

Despite Sarah’s account, which clearly described penetration, the medical evidence presented was ambiguous. Dr Archibald Grant Black said that he had examined Sarah on 12 February and found ‘some dilation at the entrance of the vagina’, though ‘the hymen was intact’. On cross-examination he observed that the:

dilation could be caused by a man having connection with her…and still leave the hymen intact…The hymen would not necessarily burst on connection as described by the girl. The dilation was too much for a girl of her age but her symptoms were consistent with her evidence today.

Nevertheless he agreed: ‘It is probable that the hymen would burst if Martin put his penis into her as described by the girl’.

Gertie Bigwood’s evidence

Gertie Bigwood’s evidence was even more graphic. She too had been into Martin’s shoe shop and described how he had exposed himself to her and asked her to expose herself to him. Afterwards he gave her a penny. Although he had not touched Gertie on that occasion, she alleged that he had ‘put his hand on my privates’ on another occasion, and added that he told her that he had ‘f…d’ the ‘girl that goes around begging’. She also claimed that he had offered her sixpence to go into the back room with him but ‘I would not because I thought he would put me on the floor and put something into me.’ (court transcript of evidence)

The verdict

Called to give evidence, Henry Martin simply denied everything, claiming that another man was also present in the shop at the time. However after a visit to the premises in question, the jury found Martin guilty. A question to the prosecutor from the Bench then revealed that Martin had appeared previously on a similar charge, but the case had not proceeded. In pronouncing sentence Justice À’Beckett commented: ‘the only thing to be said in mitigation of the prisoner was that he was not the first to commit an offence on the child, and met with no resistance.’ Martin was sentenced to three years’ imprisonment, served at Pentridge Prison. (Argus, 27 February 1904, p. 19). From his prison record we learn that Martin was married, but living apart from his wife.

‘Taken off the streets’

In delivering their verdict on the Martin case the jury had commented that: ‘Constable Crisfield was to be complimented for having arrested the children and taken them off the streets.’ Their comment reflected widespread public concern about street children and their propensity to enter a life of crime. In the case of girls it was feared that life on the streets would also lead to a life of immorality.

The following week, both girls appeared in the City Court for the adjourned hearing of their charges of ‘being neglected children.’ This time they appeared before Police Magistrate Mr Panton. The Age correspondent commented: ‘The evidence showed the children to be either remarkably ignorant or lamentably depraved morally.’ Mr Panton had dealt with many cases of child neglect and seems to have been preoccupied with the number of children begging in the streets. In his view, this placed them in grave moral danger. If Sarah and Gerties’ experiences were anything to go by, it may be that he was right. In any case, the police had little difficulty in convincing Mr Panton that Sarah and Gertie would profit by time in ‘the Schools’ and they were duly committed to the care of the Department for Neglected Children.

To ‘the Schools’

Industrial and reformatory institutions were created in Victoria through the Neglected and Criminal Children’s Act (1864). Initially they were run by the state, but increasingly from the 1870s they were managed by private organisations, including the Salvation Army (for Protestants) and the Sisters of the Good Shepherd (for Catholics). ‘Industrial training schools’ were designed for ‘neglected children’, while reformatories were aimed at children who had committed criminal offences. However the lines between the two were often blurred, and many neglected children like Sarah and Gertie, who were found ‘guilty’ of ‘depraved conduct’, were sent straight to the reformatories.

In this case Sarah was sent to Murrumbeena Reformatory, which at that time was run by the Salvation Army. Murrumbeena was said to be one of the kinder reformatories. Located in a large house on the outskirts of Melbourne, it was surrounded by an extensive and well-maintained garden. The Salvation Army only administered Murrumbeena for 13 years from 1899, but their archives still hold some photographs showing both inmates and staff. They are reproduced here by courtesy of the Salvation Army Heritage Centre Melbourne. Since the time overlaps with Sarah’s time at Murrumbeena, we like to think that she is one of the girls shown here, but of course we can’t be sure. Unfortunately the photograph is not dated.

Calisthenics at the Murrumbeena Girls Home, c.,1910

Reproduced courtesy Salvation Army Heritage Centre Melbourne

Gertie, in line with her religion (Roman Catholic), was sent to Oakleigh Reformatory, which was administered by the Sisters of the Good Shepherd.

The registration pages for the girls, held in the archives of Public Record Office Victoria, are also shown here – Sarah at Murrumbeena and Gertie at Oakleigh. In each case the ‘cause of commitment’ was recorded as: ‘Found wandering and leading a depraved life’. Interestingly each girl’s mother was also named, with a brief description. Ellen Bigwood was described as ‘Charwoman, poor, bears a good character. Has 3 children at home.’ Sarah’s mother, here called Maria Lawton, was simply described as ‘respectable’. By this time it seems that Sarah’s father might have returned home too. He is named as William Lawton, ‘Laborer [sic], poor circumstances. Respectable. He is ill and unable to work.’ The Lawtons’ address had also changed once again. They were still living in Collingwood, but now two streets away at 33 Down Street.

Gertie remained at Oakleigh for two years, after which she was sent out to service with a Mrs Martin Larkin. Sarah remained at Murrumbeena until 1912. She had a brief period in service with a Mrs Lambert in Balaclava in 1911, but returned to the home within two months. The last entry on her record in April 1912 said simply ‘Remaining in Home.’ All in all Sarah spent at least seven years at Murrumbeena – twice the length of Martin’s sentence.

Postscript

Records like these allow us brief glimpses into past lives. Sometimes it is possible to trace subsequent histories through other official records, like those held by the Registry of Births Deaths and Marriages Victoria, or through the courts or police records and/or newspaper reports. In the case of Sarah and Gertie we did manage to find some additional information. Each girl bore an illegitimate child shortly after leaving state care. Gertie gave birth to a daughter, Fran, in 1913 in Collingwood. No father’s name was recorded. Gertie was then aged about 21. She does not appear to have married and there is no record of her death in Victoria. Sarah gave birth to a son, Leonard Victor, at the Women’s Hospital in Carlton in 1915. She was also aged 21 years at the time. No father’s name was given. Five years later, on 14 February 1920, she married widower Frederick Ryall Crawford, a 31 year old boot finisher. Sarah’s occupation was given as ‘home duties’ and both gave their address as 7 Garfield Street Fitzroy. From the marriage registration we learn that Sarah’s father had died in the interim, but that her mother was still alive. No children from the marriage were traced.

A repeat offender

Of Edward Henry Martin, however, there is abundant evidence. Clearly this was no isolated offence for Martin. The first such offence we know of was in reported in May 1903, when Martin faced a charge of indecently assaulting a little girl of ten. The story is a familiar one. The child was sent to Martin’s shop by her mother to try and find a pair of boots. Martin took her into the back room, where he allegedly assaulted her. She cried, but did not tell her mother until that evening. The mother immediately went down to Martin’s shop with her daughter to confront Martin, who denied that the assault had taken place. Later both the child’s parents went to the shop to demand an explanation. When none was forthcoming they informed the police. Martin first appeared in the Collingwood Police Court on 2 May 1903 and the case was set down for trial. Martin then appeared in the Criminal Court before Mr Justice Hodges on 22 May. However Justice Hodges was not convinced that the child understood the meaning of an oath and decided that she could not be sworn. A nolle prosequi was recorded. This was a common outcome for cases involving young children, especially those in which there was no other witness to the alleged offence.

After his 1904 conviction Martin next appeared before the courts in 1915. By this time he was 46 years old and had moved to the middle-class suburb of Canterbury in the then outer east, perhaps to avoid returning to an area where his previous conviction was known. On 7 May 1915 he appeared in the Camberwell Police Court charged with having indecently assaulted a 12 year old girl in his shop on 19 April. The story is a familiar one. Florence Crump had been sent to the bootmaker, some five minutes from her home, with some shoes for repair. On a ploy of measuring her foot for shoes, Martin allegedly felt far up her leg. Any other particulars were not reported in the newspapers. Frightened and crying, she immediately ran home and told her mother: ‘Mr Martin has been so rude to me. He did such a rude thing to me’. (Truth, 8 May 1915, p. 5) Florence’s father immediately went to confront Martin, with Florence, and it was alleged that Martin admitted to part of the offence, saying ‘I know I’m a villain. I’m not worthy to live’. At the Camberwell Court he was committed for trial at the Supreme Court.

Martin appeared before the Chief Justice Sir John Madden on Tuesday 18 May. In the evidence submitted to the court on this occasion it was alleged that Martin had admitted the offence, ‘calling himself a miserable scoundrel who was not fit to live’. In court Martin admitted to part of the offence, but denied any ‘indecent intent’. The jury was not convinced however and found him guilty as charged, at which point his previous offence was also made known. In passing sentence Justice Madden called Martin ‘a dangerous individual’ and remarked that ‘the sentence he had previously received had in no wise tended to reform him.’ He contemplated sentencing him to a ‘whipping’, but ‘decided instead to impose the maximum sentence, three years’ imprisonment, with hard labour.’ (Truth, 22 May 1915, p. 7) The Truth’s headlines summed up their attitude ‘A SOCIAL LEPER/Beastly Bootmaker severely sentenced.’ The Age also reported the case, although with more restraint (and less detail) (Age, 19 May 1915, p. 14), as did the Woman Voter. Under the heading ‘SEXUAL CRIME’, the Woman Voter asked:

Is the man any more likely to be reformed after another three years in Gaol? Proper reformative treatment must go with the imprisonment, or the last state of the man will be worse than the first, and infinitely more dangerous to little girls. (Woman Voter, 27 May 1915, p. 2)

Trove was of great assistance in finding reference to Martin’s first and later offending history. His prison record lists no further convictions after 1915.

Legal process – an evolving field

When reading through the police evidence and witness statements included with the court transcripts it is immediately obvious that a great deal has changed in the management of matters involving children. In 1904 the creation of a separate children’s court was still two years away in Victoria, but even when it was created, it did not deal with matters like this in which the offender was an adult. Young children were still required to give evidence in court rooms crowded with adults and until the 1960s, before all-male juries. Just reading through the transcripts we can identify a range of procedural challenges for girls in particular.

We list just a few of them here.

- When first arrested Sarah and Gertie were taken to the ‘Detective Office’ in Russell Street police station where they were questioned by Constable Crisfield and Detective Dungey. At this time there were no female police officers, and there is no indication that any woman was present while they were questioned. Both girls were questioned in detail about their experiences. Their mothers do not seem to have been informed at this stage, and after questioning the girls were placed with Miss Sutherland in La Trobe Street. Miss Sutherland was a well-known charitable worker who provided care for neglected and orphaned children, especially girls

- The police then went straight to Martin’s shop and confronted him with the details of the allegations. They took Martin to Miss Sutherland’s house and the girls were asked to repeat their allegations in front of Martin. Sarah and Gertie do not appear to have been intimidated by this, but many would have been. Martin was subsequently charged, but so were they – as neglected children. The next day they appeared in the Police Court, where they both ‘wept bitterly’. By this time their mothers had been informed and both also appeared in court. The girls were sent to ‘the Schools’ for 14 days while police enquiries were conducted.

- During this period of detention Sarah was physically examined by Dr Black. It is not clear whether anyone else was present during the examination or whether Sarah’s mother’s permission was obtained beforehand.

- The Supreme Court trial was once again heard in an open court and the proceedings were fully reported. No attempt was made to suppress the children’s names or the general nature of the offences, although some of the more graphic detail was withheld, as was some of the language the children used to describe their experiences. This was probably to protect newspaper readers from exposure to ‘indecency’ rather than a reflection of any concern for the children. There is no reference to any support being provided to the girls during the court process and both were cross-examined in the court before Martin. While again neither Sarah nor Gertie appears to have been reluctant to give evidence, there were many children who found this process so terrifying that they could barely speak. Some cried so bitterly that they could not give evidence and were then threatened with contempt of court. (see Jennifer Anderson’s paper on this aspect of proceedings.)

- Both girls were also cross-examined to ensure that they understood the meaning of an oath. Sarah’s response was recorded: ‘When I kissed the bible in the witness box I knew I was not to tell a lie. I do not know what would happen if I told a lie. If I told a story in the box I know I would go to gaol.’ Her little sister Violet, aged eight, also gave evidence. In her case a Justice of the Peace certified that although he did not think she understood the meaning of an oath as such, he believed she was ‘possessed of sufficient intelligence to justify the reception of the evidence and understands the duty of speaking the truth.’ However the child who gave evidence against Martin in his first trial was judged incompetent to give evidence, even though she was two years older than Violet and seemed to understand the need to tell the truth quite clearly.

- After the trial both girls appeared in the Police Court once again for their charges of neglect. This was a brief appearance. The evidence they had given in Martin’s trial was more than enough to convict them of ‘being neglected children,’ and they were immediately sent to the ‘Schools,’ which meant that they were committed into the care of the state. At this time, a committal for neglect meant that children were automatically made state wards until they turned 18, although this period could be extended until the age of 20 in some circumstances, unless they were discharged earlier. Whilst still a state ward, Gertie was sent into domestic service, a common pathway for teenage girls. Sarah also went out to service briefly, but then returned to Murrumbeena where she remained until 1912. By that time she was 18 years old.

This account has been drawn from the following original records held by Public Record Office Victoria:

Trial Brief The King v Edward Henry Martin, 15 February 1904, PROV, VPRS 30/Po, unit 1348

Ward registers PROV, VPRS 4527/Po, unit 68, volume 42

Prison register for Edward Henry Martin PROV, VPRS 515/P1, unit 57.

Additional material was accessed from the Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages, Victoria and Victorian newspapers as cited.

Further reading

Jennifer Anderson, ‘Using the Law: Working-Class Communities and Carnal Knowledge Cases in Victoria, 1900 – 1906,’ in Diane Kirkby (ed.) Past Law, Present Histories. Canberra: ANU e-Press, 2012.

Jill Bavin-Mizzi, Ravished: Sexual Violence in Victorian Australia Sydney: University of New South Wales Press, 1995

Jill Bavin-Mizzi, ‘Understandings of Justice: Australian Rape and Carnal Knowledge Cases, 1876–1924’, in Diane Kirkby (ed.) Sex, Power and Justice: Historical Perspectives of Law in Australia Melbourne: Oxford University Press, 1995.

Andy Kaladelfos, ‘Murder in Gun Alley: Girls, Grime and Gumshoe History', Journal of Australian Studies, Vol. 34, Issue 4, 2010.

Yorick Smaal, Andy Kaladelfos and Mark Finnane (eds) The Sexual Abuse of Children: Recognition and Redress Clayton: Monash University Publishing, 2016.