Australian women have been key organisers of peace activism since the foundation of the Australian Section of the Women’s International League of Peace and Freedom (WILPF) in Melbourne in 1920. In Melbourne, the first big protest against nuclear weapons was held at the Assembly Hall on Collins Street in August 1946. This meeting, which focused on opposing the use and manufacture of atomic bombs, was organised by the editorial board of the lifestyle magazine Women’s Digest. Along with communist organisers, women dominated peace activism and would drive the development of anti-nuclear protest in Victoria and Australia over the next decades.

The Nuclear Age

The Nuclear Age burst onto the global stage dramatically in August 1945 when the US bombed the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Although many initially supported the attacks for ending the World War II in the Pacific, there was also widespread criticism of the cruel impact of the atomic blasts in the days and months after the attack. But despite the fear that nuclear weapons engendered, they would become an inescapable part of the ‘new normal’ of the Cold War. The Soviet Union tested its first nuclear weapon in 1949 and from then it became a race between the US and the Soviets over who held the most nuclear weapons.

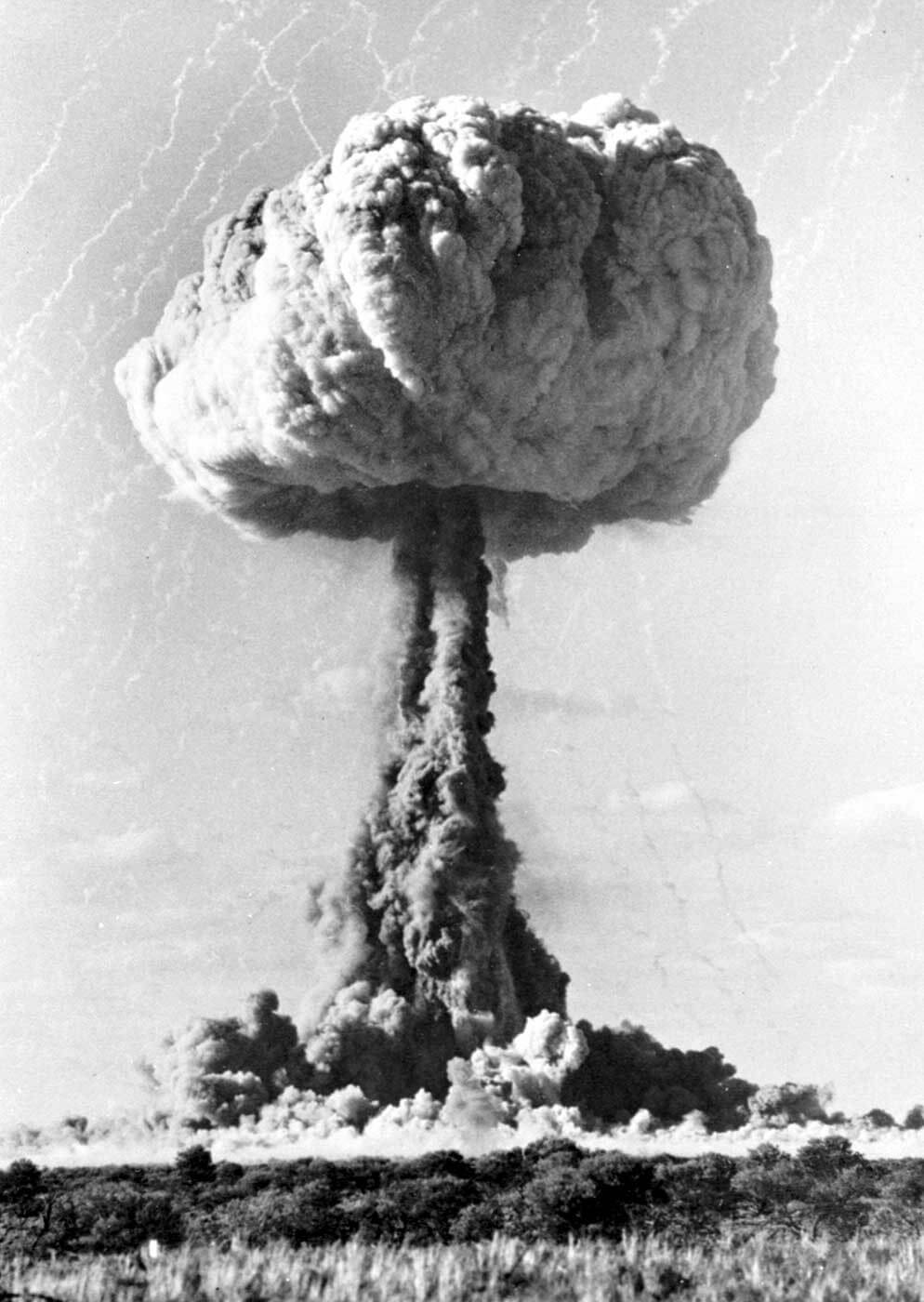

Atomic blast during Operation Buffalo nuclear tests, Maralinga, South Australia.

Image courtesy National Archives of Australia.

The Nuclear Age in Australia

Australia was brought directly into the Nuclear Age in 1952 when British atomic weapons tests began on Australian soil, first at the Monte Bello Islands off the coast of Western Australia, then at Emu Fields, and eventually at Maralinga in South Australia. Although some were concerned about the dangers of fallout, the Minister for Supply Howard Beale promised that ‘there would be no danger to people or stock on the mainland’ and that ‘the tests would take place only when weather conditions were satisfactory.’

‘Series of Atom Bomb Tests Planned in 1956’, Canberra Times, 13 September 1955.

This was, of course, misleading information, as the testing site was on the lands of the Maralinga Tjarutja people. The 1980s Royal Commission into British Nuclear Tests in Australia revealed that the British nuclear tests were devastating for the Maralinga Tjarutja people, both from the health effects of fallout and from the forced removal from their lands.

Anti-Nuclear Campaigning in Australia

After the widespread support for the Allied cause in World War II, the Australian peace movement was small at the end of the 1940s and struggled to win support from the wider public. This was, in part, due to the large influence of the Communist Party of Australia (CPA) in the movement. This period of peace activism was dogged by pervasive anti-communist sentiment within broader Australian society. Echoing rhetoric put forth by politicians such as Prime Minister Robert Menzies, many Australians feared communist infiltration in the country. The dominance of communists and communist organisations in peace activism in Australia and around the world convinced many that it was a ‘front’ for communist subversion.

The industrial activities of the Communists prove them to be destructive and disloyal, a fifth column for a potential enemy. Why should Communists do these things? The answer is that Communism is a materialistic doctrine, void of spiritual content. It is not only anti-Christian, but is opposed to all those nobler aspirations which spring from the religious faith of decent people. True, Communism itself has been called, by some, a religion. But it is a religion of hatred; it derives from the darkest recesses of the human mind; it has nothing in common with the Christian gospel of love and brotherhood. If it had, it could not preach the class war or use envy and malice as its characteristic weapons.

In this great and free country of ours we have at least learned that hatred of other men is no instrument of progress but is merely a sign of decadence and despair.

When, therefore, I say to you that the Government is pledged to make war upon Communism I am not talking about an attack upon individuals as such (though we are determined to root out key Communists from key positions), but upon a set of evil ideas which are quite foreign to our civilisation, our traditions, and our faith.

Those who persist, as does the Leader of the Opposition, in regarding Communism as just some variant of democratic political philosophy entirely overlook the fact that Communism is debased, treasonable, utterly undemocratic; in form a subversive conspiracy; in practice opposed to high standards of living and real prosperity; destructive, if it succeeds, of all human freedom.

We are pledged to fight it, and to defeat it.

- Robert Menzies, ‘Election Speech’ (Canterbury, Victoria, 1951)

WILPF and Anti-Nuclear Activism

Apart from the CPA, WILPF was one of the largest peace organisations concerned about nuclear weapons in the early 1950s. On the sixth anniversary of the first atomic bombing at Hiroshima, the Australian Section of WILPF organised a meeting in Melbourne to ask, ‘must it happen again?’ Nuclear disarmament quickly became one of the key issues of concern for WILPF, both globally and domestically. Under the Honourable Secretary of the Australian Section, Anna Vroland, WILPF was particularly concerned with the impact of British nuclear tests on First Nations peoples in the testing areas. Anna Vroland was a dedicated advocate for First Nations Australians throughout her life and was concerned that not only were nuclear weapons tests a mere step away from nuclear war, but ‘already to aboriginal people, the tests have been utterly disastrous.’

Women’s Role in the Movement

Women’s labour and dedication were crucial in the first decades of the anti-nuclear movement in Melbourne, although their labours were often unseen. One of the many mixed peace organisations, the Australian Peace Council (APC), was formed in Melbourne in July 1949. Although men were often the public face of these organisations—the so-called ‘peace parsons’ who fronted the APC, for example—women’s labour drove the organisation behind the scenes. Women were in key positions as secretaries or treasurers, roles which might seem less important, but were, in fact, central to the effectiveness of the organisation’s activities.

There were some women, however, who believed they should take a more visible role. Following in the tradition of suffrage campaigners from the beginning of the twentieth century, some women anti-nuclear activists realised the necessity of placing themselves at the centre of debates, ensuring that their voices were heard. Anna Vroland regularly wrote to the media to ensure that ‘the view of informed women’ was ‘sufficiently widely known.’

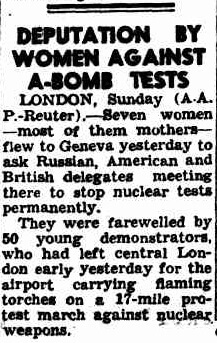

Women as Mothers

Women’s maternal role was central to their visible activist identity. Although never a mother herself, Aileen Palmer was convinced that it was women’s role as mothers, or potential mothers, that was the reason they were ‘beginning to understand they must take a foremost place in the struggle against A and H bombs.’ As mothers, this argument went, women had a duty to protest nuclear weapons and fight for peace to defend their children. This argument was used repeatedly by the Union of Australian Women, who positioned their activism as a natural maternal instinct. The first sentence of a brief article in the Canberra Times sums up clearly the emphasis newspapers placed on the maternal nature of these women. Reporting on a group who had flown to Geneva to campaign for unilateral disarmament, the Times opened the article by introducing them as ‘seven women—most of them mothers’.

On the other hand, this was also a factor preventing many women from active campaigning. Women had the added burdens of childrearing and homemaking, as well as paid employment for many, on top of any protest activities. Meetings were often held midday during the week, preventing women who worked from attending and limiting the women who could dedicate the time necessary to largely middle- or upper-class women who did not work and were not responsible for young children.

The Victorian Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament

The Victorian Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (VCND) was formed in Melbourne in May 1960 by young intellectuals inspired by the British CND formed two years earlier. VCND formed in opposition to the perceived politics of the earlier peace movement, which was often centred around socialist activists or dominant figures within the Communist Party of Australia (CPA). In contrast to the more moderate tactics of the mainstream peace movement, VCND wished to follow the pattern set by anti-nuclear activists in Britain and use civil disobedience to agitate for unilateral nuclear disarmament.

Early Activities of the VCND

The first members of VCND were based at the University of Melbourne. They were early examples of an expanding group of ‘New Left’ student protesters in Australian universities, who rejected the more rigid divisions of the Cold War. Both the widespread fears of communism and the strict bureaucratic nature of the CPA meant that peace organisations were often strictly aligned to communist or non-communist camps. Though some early activists dismissed these as arbitrary divisions, it was not until the early 1960s that the peace movement more generally began to adopt a broader, more inclusive approach. VCND marked a turning point in peace activism, as fears of communism lessened, by consciously adopting a more open policy. Like the CND organisations that would follow it in Brisbane, Sydney and Perth, the VCND membership consisted mostly of students, middle-class activists and white-collar professionals. Unlike earlier peace organisations that had adopted nuclear disarmament as only one among many issues of concern, VCND was exclusively anti-nuclear.

ASIO surveillance photo showing Carol Goldson bottom left, from ASIO, ‘HOLDSWORTH, Roger Maxwell’ (1966-1969), A9626, 674, National Archives of Australia.

Carol Goldson

One of the key women involved in VCND was Carol Goldson, known also as Carol Siansky and Carol Holdsworth. Carol was seven years old when the atomic bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945 and was conscious of the threat of nuclear weapons growing up. She was born in Melbourne and educated at a Catholic primary school, despite the fact that her parents were former Communist Party members. During her primary schooling, Carol was exposed to anti-communist views through her teachers, the nuns warning the students that communists were terrible people who would ‘come in and hang the nuns and priests’. For young Carol, this message was confusing, given she knew some very non-threatening communists – her parents. This marked the beginning of Carol questioning the different beliefs and attitudes of those around her. She identified as a practising Catholic until the age of 13 but as she got older, Carol found her beliefs more closely aligning with that of her parents. This change in attitude was, in part, shaped by her time at University High School. While there, Carol was exposed to new ideas and it was there that she decided she was no longer a Catholic.

Carol began to worry about nuclear weapons as a young teenager. She remembers there was a lot of talk about the possibility of nuclear war and threat posed by nuclear weapons. It was around this time that she read a book about the aftermath of the Hiroshima bombing, which affected her profoundly.

Transcription: I can remember being when I was about 15 looking at the young, young children and thinking, feeling really sorry for them, because, you know, thinking they probably won't get to be my age before something terrible happened. So it's easy to forget how, how those, those things can be so such a preoccupation, but then, yeah, it was. I guess it might be similar to what a lot of younger people are feeling now in the face of climate change. I don't know, but I suspect it must be something like that.

After high school, Carol worked in administration at Melbourne University and soon met her first husband, Peitro (Peter) Siansky, through a Ukrainian dance group. They married when Carol was 18 and had a daughter but the marriage did not last. Carol moved back in with her father and grandmother and began studying Arts at university part-time. It was during this period of her life that Carol joined the VNCD in about 1963, in her early twenties. It was at the university that Carol would have picked up a flyer from the organisation, which sparked her interest in joining a formal anti-nuclear group, where she could be part of a structure working towards nuclear disarmament. Carol rang the number on the flyer for more information and ended up going to a meeting. The previous VCND committee was outgoing and so in 1964, she became Assistant Secretary before becoming the VCND Secretary in 1965. She remarried in 1966 to Roger Holdsworth, with whom she had another child. While juggling her duties as Secretary of the organisation, Carol was also studying part-time, raising her children, and working full-time, first in the mailroom at Ampol Petroleum and eventually as a teacher at Brunswick Girls School.

Youth and Anti-Nuclear Activism

Carol was often an ‘ad hoc’ campaigner over her lifetime, but nuclear disarmament was one issue that especially concerned her. When asked why she felt so strongly about nuclear disarmament compared to other issues, Carol revealed that it was, in fact, her age that drove her to the movement.

Transcription: I think that, yeah, the youth, I think, and the way things, things are so urgent when you're young and not today, they're not now, but that sense that, that sense that I have to do something about this, this is, this is terrible. We're all gonna die, but yeah. But yeah, there was that, I think it was that. And, and I suppose being at that stage of life, it certainly was true for me that I thought I could do something that might make a difference what I do, which I’m afraid I no longer feel that. I feel we probably should do things because it's the right thing to do, but you know, as for the expectations, that’s another matter.

Radicalisation in the Movement

Young women like Carol, who joined the anti-nuclear movement in the 1960s, had come of age in the 1950s. This was, for most, a period of overt conservativism, but it also saw the beginnings of a youth culture centred around radicalism and youthful rebellion. For young women in particular, the 1950s was a period when some teenage girls were beginning to question the traditions and values of their parents. Experience in organisations like VCND provided an opportunity for young women to move outside the expectations placed upon them by society: marriage and motherhood. For Carol, VCND was her social life, a place where she could get away from the day-to-day realities of working, studying and raising children.

Transcription: Well it played a big part at the time and, and of course, you know, the friendships I made then … have sort of flowed through the rest of my life and, you know, some people that perhaps I wasn't directly in contact with then, but whom through contacts I made then, I subsequently, you know, became involved with, you know, have had a big effect in my life. It just, I suppose, yeah, it sort of opened up a whole, a whole range of, of contacts and networks that weren't directly connected to that CND, but, you know, broadly that sort of flowed from that, in fact, probably nearly, nearly all one way or another. I mean, I've found for instance in later life in places I've worked or, you know, maybe schools I worked in, particularly I would be in contact with people who had been part of the broader peace movement back in those days. Yeah, it was all wider than it seemed at the time, I suppose.

In fact, anti-nuclear activism introduced many young women to radical politics. Their participation in the anti-nuclear movement also represented a space outside the more conventional opportunities available to them. Nuclear disarmament activism was also fun and thrilling, a social activity as much as a political one, and offered these young women a chance to broaden their horizons. This was one of many ‘layers of motivation’ for young women. The cause of nuclear disarmament was, by itself, important. Yet a chance to go out demonstrating with friends also offered a sense of freedom and escape from the realities of everyday life.

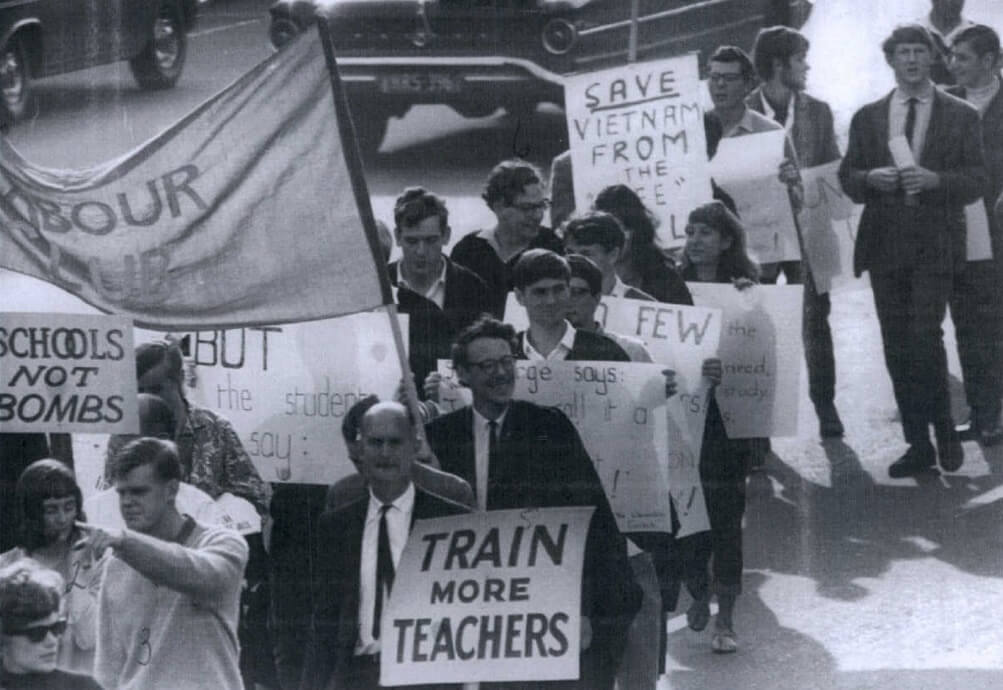

The Anti-Vietnam War Movement

The Australian Government announced the National Service Scheme in November 1964. Five months later, in April 1965, Prime Minister Robert Menzies announced that Australian troops would be sent to Vietnam. Almost overnight, anti-nuclear and peace groups pivoted to protesting against the Vietnam War, with a particular focus on Australian involvement and on conscription. In May, the organisation ‘Save Our Sons’ (SOS) was founded in Sydney by Joyce Golgerth, whose son had just been ‘called up’ in the conscription ‘lottery.’ Soon, women across the country joined the cause.

Transcription: The urgency died away a bit and there were serious moves to come to an agreement which subsequently happened of course, where international agreements were reached. Where, you know, non-proliferation was the goal. But then in the meantime, the, the Vietnam War blowing up, that became, that became the urgent issue. So although, I guess anybody who'd previously been concerned about the possibility of nuclear war and the, you know, the, uh, the dangers of, you know, nuclear energy generally still felt the same. But it sort of had receded a bit into the background. That's what, that's my perception.

And, and then of course, you know, a lot of women were, who perhaps weren't as perhaps fired up to actually do anything much about the nuclear question were, oh, energized during the Vietnam War period by, you know, the fact that young Australian men were being conscripted and you had, you know, the rise of Save Our Sons, which was, you know, I guess it just all was so close and so real that a lot more people could, could be galvanized into doing something.

Women and Anti-Vietnam Protest

Through SOS, women became one of the most visible groups of anti-Vietnam campaigners. Their activism continued to make use of the motherhood motif employed by anti-nuclear activists. SOS members always wore respectable and sensible clothing and framed their actions around protecting their sons – even if their activities sometimes landed them in jail. In the beginning, SOS employed more peaceful and lawful strategies, including petitions and silent vigils. As the war and conscription continued however, they turned to more radical tactics, including wearing revealing anti-war outfits to the Melbourne Cup or refusing to pay their taxes.

Peace Activism and Women’s Liberation

The same period saw the emergence of the Women’s Liberation Movement, a movement that demanded an end to all discrimination against women. Women protesting nuclear weapons or the Vietnam War in public spaces had often attracted criticism not levelled at men, namely, that they were ‘bad mothers’ or ‘bad wives’. Such criticism came from both men and women. Perhaps not surprisingly, there was significant overlap between peace activism and the Women’s Liberation Movement in the late 1960s and early 1970s. This was by no means straightforward, and there were tensions between the basic ideals of the two organisations. Many in the emerging WLM for example, rejected the maternalist tactics used by SOS which they saw as a backward step. Some older members of the peace movement on the other hand, were uncomfortable with the more radical tactics used by the women’s movement. The tensions reflected changing attitudes both of women and towards women at the beginning of the 1970s and the lively debates about what it meant to be a woman in the last decades of the twentieth century. Largely, however, exposure to protest tactics in anti-conscription or anti-war organisations was often the place where younger women cut their activist teeth. And, for some women, experience of sexism within the anti-Vietnam movement pushed them to campaign subsequently for women’s rights.

Anti-Nuclear Activism after the Vietnam War

Although anti-nuclear protest waned in the period of the Vietnam War, tense relations between the US and the Soviet Union in the early 1980s reignited fears of global nuclear annihilation dramatically. They were exacerbated by growing environmental concerns about nuclear power plants, which would be particularly evident after the 1986 Chernobyl disaster. People for Nuclear Disarmament (PND) was formed in 1981 in Melbourne, and Victoria was the base for much of the 1980s anti-nuclear protest.

Women’s anti-nuclear activism in the 1980s

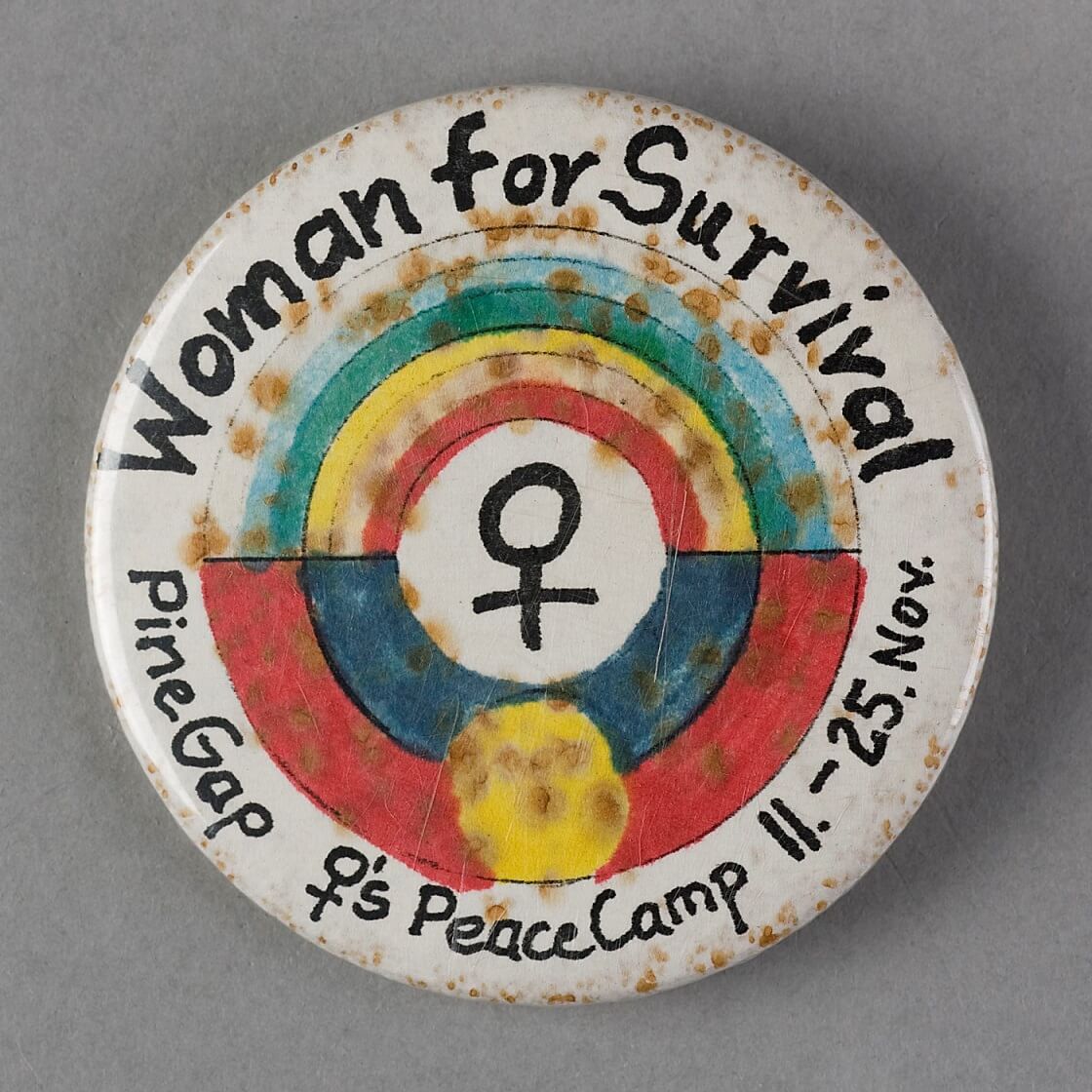

The overlap between women’s liberation and anti-nuclear activism reached its peak in the 1980s. Feminist ideologies drove extensive peace activism and inspired many women to campaign against nuclear technology. In 1983, inspired by the women’s peace camp at Greenham Common in the UK, Australian women decided to stage a two-week women’s protest camp at the US military base at Pine Gap in central Australia. Existing women’s peace groups joined together to form Women for Survival. A year later, in 1984, women again ventured en masse to protest at the US Stirling Naval Base at Cockburn Sound in Western Australia. Although the women involved did not all identify as feminists, women’s peace activism in this period was increasingly driven by radical feminist ideology – in this case, the view that nuclear war and nuclear proliferation was a symptom of a patriarchal society. This was reflected in one of the most prominent slogans of the movement: “Take the Toys from the Boys.”

Badge - 'Take the Toys From the Boys', circa 1960s-1980s. Photographer: Benjamin Healley. Source: Museums Victoria.

Badge, 'Woman for Survival', Pine Gap, Women's Peace Camp, 11-25. Nov, 1983. Source: Museum of Applied Arts & Sciences

Women’s activism and peace campaigning in the 20th century

Although women’s contributions to peace activism after World War II are generally glossed over prior to their involvement in Save Our Sons and the anti-conscription campaign of the 1970s, for most of the twentieth century, women’s and peace activism repeatedly intersected and converged. This was particularly apparent in the anti-nuclear campaigns of the 1960s and the 1980s. Women were crucial early drivers of peace activism right from the beginning of the century, and their involvement in peace activism would, in turn, provoke and encourage new ways of looking at the world that came to the fore during the Women’s Liberation Movement. By the 1980s, feminist activism was inextricably intertwined with peace activism. Women’s anti-nuclear activism has resulted in very few concrete achievements both nationally and internationally, yet the impact of women’s participation in these early peace campaigns went far beyond whether nuclear weapons were banned or world peace achieved.

Author: Hannah Viney

Further Reading:

Ann Curthoys and John Merritt, eds., Better Dead Than Red (Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 1986).

Jon Piccini, Evan Smith, and Matthew Worley, eds., The Far Left in Australia since 1945 (Abingdon, Oxon ; New York, NY: Routledge, 2018).

Malcolm Saunders and Ralph Summy, The Australian Peace Movement: A Short History (Canberra: Peace Research Centre, Australian National University, 1986).

Elizabeth Tynan, Atomic Thunder: The Maralinga Story (Sydney: NewSouth Publishing, 2016).

Carolyn Collins, Save Our Sons: Women, Dissent and Conscription during the Vietnam War (Melbourne: Monash University Publishing, 2021).

WILPF Australia, ‘Our History’, Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom (blog)

Suellen Murray, ‘Taking the Toys from the Boys’, Australian Feminist Studies 25, no. 63 (2010): 3–15