The first campaigns for women’s rights began in Victoria in the 1880s. At that time the focus of activity was the right to vote, for although adult men were enfranchised from 1857, women were excluded. It was to be a long campaign. Early suffragists were also concerned about access to education, about violence against women, (especially domestic violence,) and about the exploitation of women in the workforce. These were issues that continued to resonate through the decades, and remain relevant today.

The (long) campaign for the suffrage

Women in Victoria first joined together to fight for the right to vote in the 1880s. There were several suffrage societies and in 1894 an umbrella organization, the United Council for Woman Suffrage, was formed to coordinate efforts. Suffragists believed that women should have the same political rights as men, including both the right to vote and the right to stand for election to parliament. It seems extraordinary now, but in the 1880s many men and even some women, believed that women’s very nature disqualified them from voting or from holding public office. It was argued that women were less rational than men, but also that women would be tainted by mixing with men in the hurly-burly of politics. Woman’s realm was said to be the home and the maternal role her ‘highest calling’. Such ideas continued to define women’s lives until well into the 1950s and sixties.

Early suffragists did not march in the noisy protests that marked later protest movements. They were acutely aware of the need to reassure male legislators of their respectability, and often shied away from issues, like birth control, that might seem controversial. Their weapons were the petition and the dignified delegation to parliamentarians. They did hold very large public meetings however, and those meetings could become rowdy, especially when male agitators turned up to heckle speakers. Early feminists were taught how to deal with such spectators without compromising their dignity. Vida Goldstein was said to be especially adept at managing hecklers with grace and humour.

Woman suffrage, vanguard of a deputation that waited on the Legislative Council last week

Australasian, 17 September 1898, p. 26.

Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia

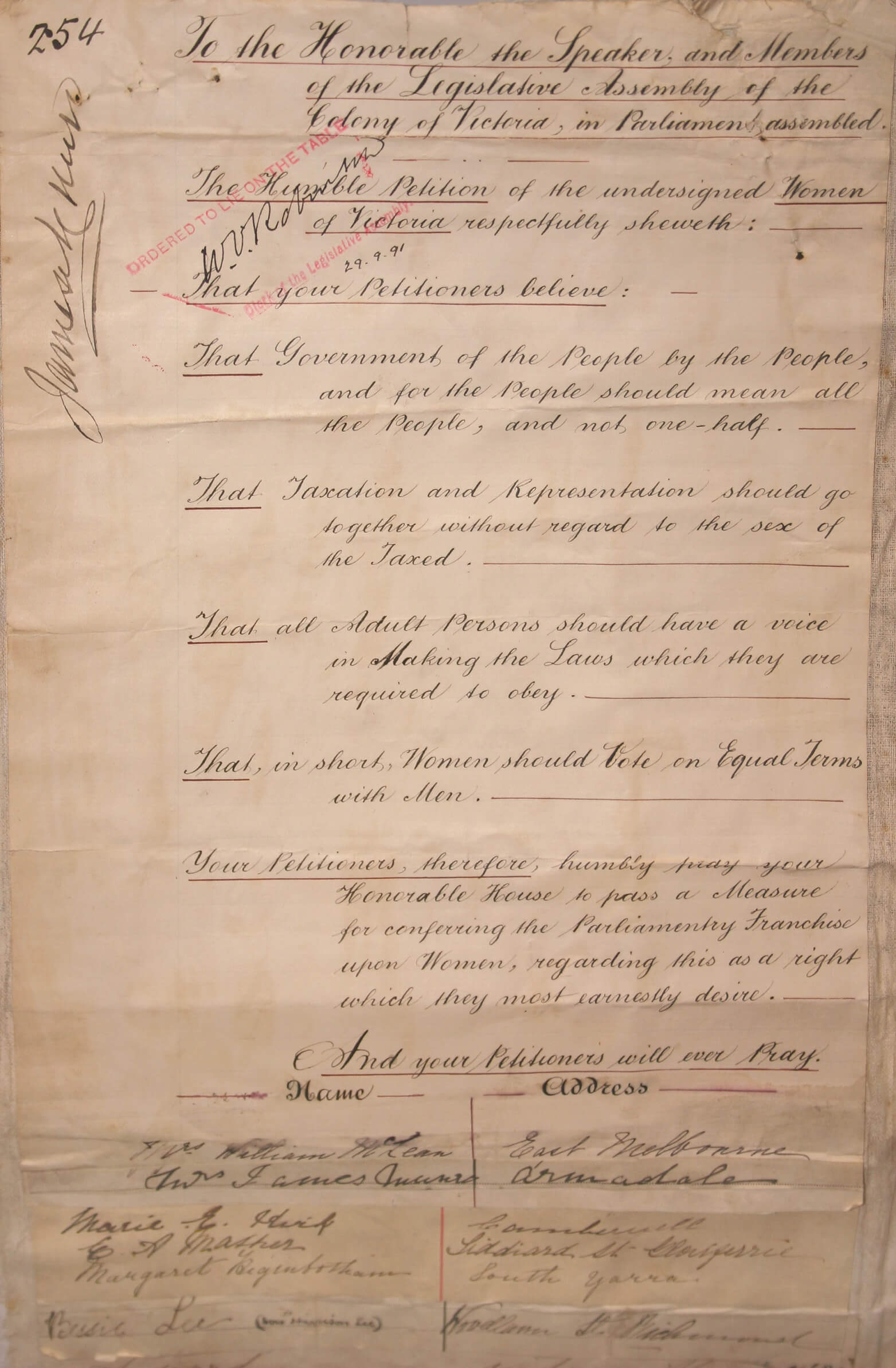

‘Monster’ petitions

The early suffrage societies were hugely energetic and gathered signatures on petitions all over the state. One such petition, the so-called ‘Monster petition’, collected nearly 30,000 signatures in 1891. It extended to 260 metres in length and is thought to have been the largest petition presented during the nineteenth century. It was so large that it had to be presented in a huge roll to the Victorian Parliament. The ‘Monster petition’ is held in the collection of Public Records Victoria and a digital copy is available online. The petition is also included on the Australian register of the Memory of the World project.

Sadly however, the petition did not convince the obdurate Victorian parliament, which refused 19 separate suffrage bills from 1889, before finally granting women the right to vote in 1908. Although the first in Australia to organise, Victorian women were the last to receive the vote. And even then they could not stand for parliament: that right was not conceded until 1924. By that time Victorian women had been full federal citizens for nearly a generation!

The ‘Monster Petition’. Reproduced courtesy Public Record Office Victoria, VPRS 3253/P0, unit 851

Although it seems incredible now, there were also women, along with many men, who opposed the extension of the suffrage. The petition below argued against women’s suffrage and was presented to the Victorian Parliament in 1900. The text of the petition repeats many of the arguments commonly presented in opposition to women’s emancipation.

Anti-suffrage petition, 1900

Reproduced courtesy Public Record Office Victoria. VPRS 2599/P0 Original Papers Tabled in the Legislative Council, unit 193

“To the Honourable the President and Members of the Legislative Council of Victoria in Parliament Assembled The petition of the undersigned women, resident in Victoria, humbly sheweth :

"That there is a Bill before your Honourable House to confer the Parliamentary franchise on women. That your petitioners are convinced that this measure will not be for the good of the State for the following reasons: - It will be the cause of dissension in families. Many women have neither the time nor opportunity to inform themselves concerning great public questions without neglecting the training of their children and the comfort of their homes. Suffrage for women will force them from the peacefulness and quiet of their homes into the arena of politics, and impose a burden upon them in addition to their present duties. The present feeling in favour of the measure will pass away, but the effect of the measure will remain.

“The women of Victoria as a body have never yet expressed an opinion upon the subject of women’s suffrage. We believe that if they had an opportunity of so doing they would be against its adoption. The movement in favour of it has been promoted by a comparatively small minority of the women in Victoria, backed by a political party which hopes to increase its influence thereby.”

Working women

Although they had the vote, women were anything but equal in other ways. They could not serve on most decision-making bodies, or on juries, and were often forced to leave the workforce when they married. Until well after World War II the Victorian workforce was strongly gendered, divided into ‘men’s jobs’ and ‘women’s jobs’. Women were paid far less than men (usually just over 50 per cent), even when they performed the same work. Single women and supporting mothers found it impossible to earn enough to live decently. Moves to improve women’s working conditions began in the late-nineteenth century with campaigns to end ‘sweating’ and other exploitive practices. Early labour women organized marches and petitions, trying to raise public awareness and support, with some success, but fundamental gendered divisions in the workforce remained.

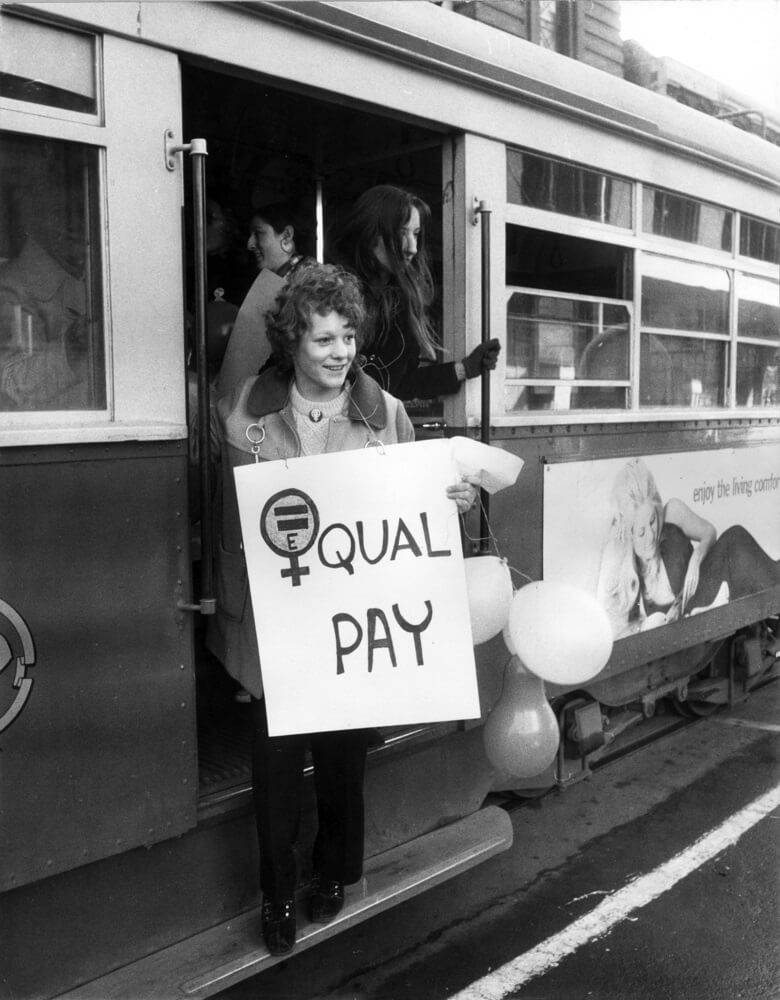

The campaign for equal pay

Feminists first began to argue for equal pay in the early years of the twentieth century, but it was not until 1937 that a specific organization was formed to campaign for reform. The Council of Action for Equal Pay was led by two remarkable socialist women – Muriel Heagney and Jessie Street – and they helped to shift the debate in favour of more equitable rates of pay, as more women moved into the wartime workforce. The Council was active from 1937-46, and although equal pay was awarded to only a few women workers during the war, women working in men’s jobs were often awarded pay increases, generally to between 75 and 90 per cent of the equivalent male rate. It was a start, although these decisions had not helped the many women working in equally ‘essential’ ‘women’s’ jobs (often in the clothing, textiles and food industries).

Munitions workers in a Bendigo factory, April 1943.

Reproduced courtesy Australian War Memorial

Images like this helped to demonstrate the competence of women in jobs previously reserved for men.

After the war, the campaign faltered. Those women who had moved into ‘men’s’ jobs were forced to leave as servicemen returned. It seemed that little had been gained. But then in 1950 the Australian Conciliation and Arbitration Court established the first minimum wage for women, set at 75 per cent of the male rate. Feminists were bitterly disappointed, but it was at least an improvement on the old rate of 54 per cent.

The campaign resumes

An active equal pay campaign resumed in the late 1950s and accelerated in the 1960s. In between radical women maintained a campaign to improve the rights of women at work. Socialist women’s groups marched each year to mark International Women’s Day on 8 March, often combining their marches with calls for peace, or universal disarmament.

Initially International Women’s Day was a socialist initiative, and was known as International Working Women’s Day. It was marked first in 1911, following the declaration of a National Women’s Day in the United States in 1909. Socialists all over the world gradually took up the call, including in Australia. The group shown marching towards the Old Treasury Building in 1962 (below) included members of the Communist Party of Australia and their placards suggest the range of issues they embraced at that time.

Women march along Spring Street, Melbourne for International Women’s Day, 1962

Communist Party of Australia Collection. Reproduced courtesy University of Melbourne Archives

In the late 1960s the equal pay campaign achieved public notoriety through the actions of a group of labour women, who took their demands for equal pay directly to the public. Zelda D’Aprano was prominent in the group. An employee of the Meat Industries Union, D’Aprano was frustrated by the continued exclusion of women from the decision-making process on equal pay claims and decided on a campaign to draw attention to the issue. In October 1969 she chained herself to the entrance of the Commonwealth Building in Spring Street in support of equal pay. The ploy worked wonderfully and this picture appeared in The Age on 21 October:

Zelda D’Aprano was instrumental in forming the Women’s Action Committee in Melbourne, campaigning for equal pay and better working conditions for women. In 1972 the Commonwealth Conciliation and Arbitration Commission finally endorsed the concept of ‘equal pay for work of equal value’, paving the way for more equitable pay and conditions for women in the workplace.

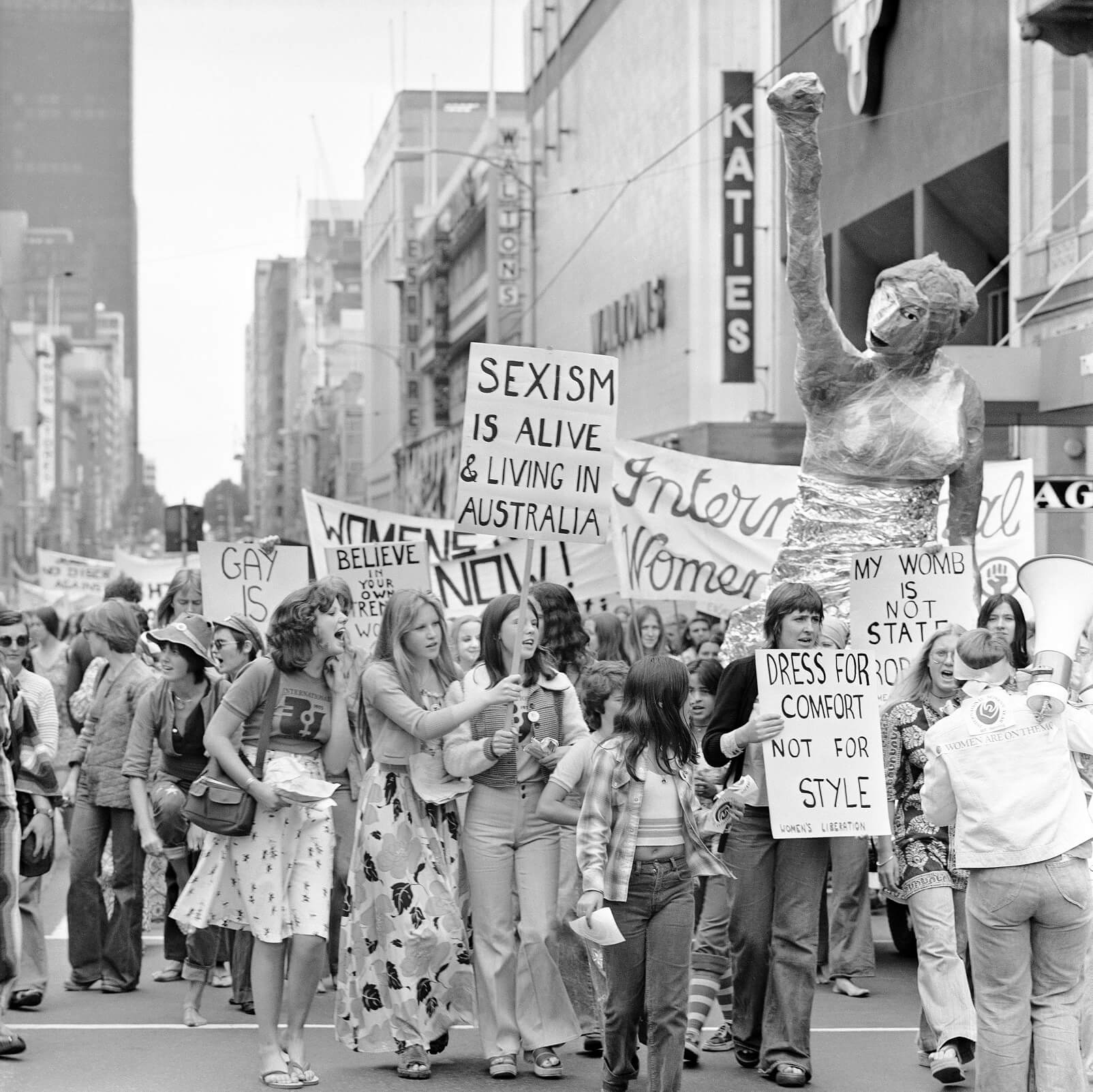

Women’s Liberation Movement

At the same time that Zelda D’Aprano and her labour colleagues were campaigning for equal pay, a more revolutionary challenge to women’s traditional position in society was emerging, at first amongst young, educated women. Known as the Women’s Liberation Movement, it demanded an end to all gendered assumptions about male and female roles. In street marches and public meetings they demanded an end to discrimination on the basis of sex or sexual preference, and campaigned for a range of reforms, including legalized abortion, affordable contraception and better access to child care. Like their earlier feminist sisters, they denounced continuing levels of violence against women and campaigned against sexual exploitation of women in all its forms. They organized huge street marches and other protests, including protests against the practice of ‘beauty contests’, which they held to be demeaning to women. While the Women’s Liberation Movement often tried to avoid all forms of hierarchical organization, others saw the need for political organization to advance the feminist agenda. The Women’s Electoral Lobby (WEL), formed in 1972, went on to become an influential force in politics at both the state and federal level.

International Women’s Day march, Melbourne, 8 March 1975.

Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia

The first UN-designated International Women’s Day saw Victorian women marching on a range of issues. Placards protested against general discrimination on the basis of sex, and in favour of gay rights, access to abortion and sensible dress styles. International Women’s Day marches often drew supporters from all so-called ‘second-wave’ feminist groups.

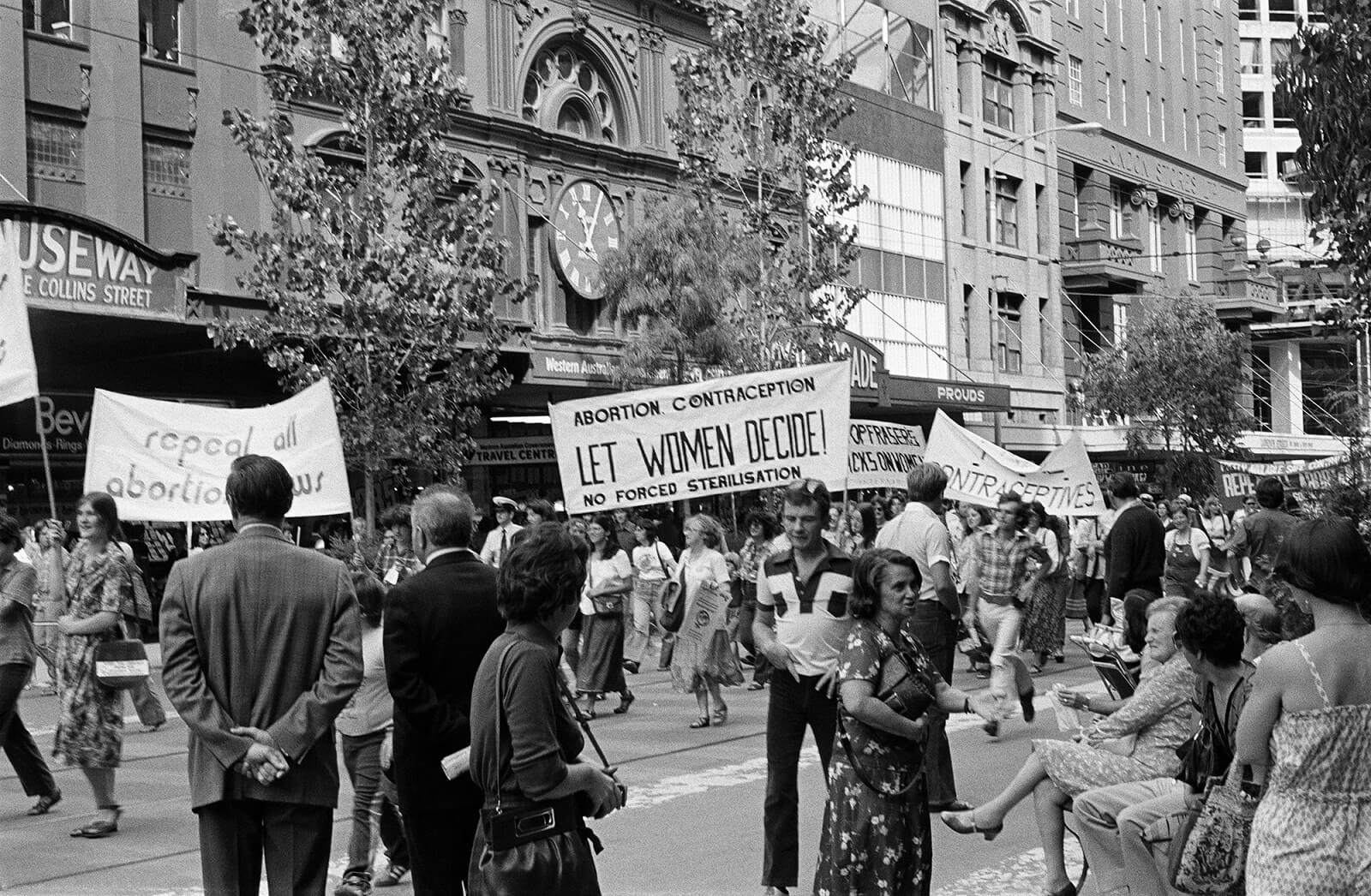

Women’s Liberation march in Melbourne, May 1979

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

The placards demand access to free and safe contraception and abortion law reform

And the fight goes on…

The decades of the 1970s and 1980s saw important reforms for women in Australia. They included anti-discrimination legislation, legalised abortion and the increased provision of child care (although still at a cost to parents). Workplace reforms continued into the 21st century. But other issues proved more resistant to change. Violence against women, both in the home and in public, continues. In 2012 ABC employee Jill Meagher was brutally raped and murdered near her home in Brunswick. Her murderer was a convicted sex offender, then on parole after five previous rapes. Public anger at the brutal attack was expressed through commemorative gatherings at the time and in this street march in Jill Meagher’s memory on the anniversary of her death.

March in memory of Jill Meagher, Brunswick, 29 September 2013

Reproduced courtesy The Age newspaper

Sadly, the incidence of domestic violence seems only to have increased during the COVID pandemic, while women also continue to experience sexual harassment, and even sexual assault, at work and in public. The Me Too (or #MeToo) phrase was first used in 2006, but became a global social media movement after 2017, encouraging women to speak out about sexual harassment in the workplace. Public outrage in Australia followed allegations by former Liberal Party staff member Brittany Higgins that she had been sexually assaulted inside Parliament House in Canberra in 2019. Protest marches demanding an end to sexual assault and workplace sexual harassment followed, when Hughes’ allegations were made public in 2021. On 4 March 2021 thousands of women marched in every capital city in Australia, united under the slogan ‘Enough is enough. March 4 Justice’.

Women's March 4 Justice - Melbourne. From the Melbourne #March4Justice.

Image courtesy Matt Hrkac.

Author: Margaret Anderson

Further reading

Marilyn Lake Getting Equal: the history of Australian feminism Allen & Unwin, 1999

Carla Pascoe Leahy, ‘Looking for the perfect Mother’s Day gift? Why not smash the patriarchy?’ The Conversation, 7 May 2021.

Susan Magarey Dangerous Ideas: Women’s Liberation – Women’s Studies – Around the Globe University of Adelaide Press, 2014

Susan Magarey, ‘Women’s Liberation was a Movement, not an Organisation’, Australian Feminist Studies, Vol. 29, no 82, 2014, pp. 378-390

Marian Sawer with Gail Radford, Making Women Count: A history of the Women’s Electoral Lobby in Australia University of NSW Press, 2008.

Beverley Symons, ‘Muriel Heagney and the Fight for Equal Pay During World War Two', Australian Society for the Study of Labour History.