-Warning-

This exhibition contains material that refers to deceased persons, and colonial records using language now considered offensive. They are included here as historical evidence.

Womin-dji-ka (Welcome)

Words, as respectful and honest as these ones are, can only express a small tribute to the awe, inspiration, empathy and empowerment we feel today for what they experienced to ensure our survival.

The pain, sadness, confusion and unjust hardships they endured and overcame are testament to the residual present day health and wellbeing of our Country and our people, their descendants.

What happened during colonisation and the following attempts at genocide challenged and tested our resilience and resistance to the degradation of our land, our culture and our people.

We are proud of and honoured by the innovative ways in which they upheld the integrity of our once silenced lifeways, traditions and belief systems.

In a time when their voice was not heard and their stories forbidden to be shared they persevered and now we have arrived to a new day where the opportunity exists to unveil storied untold.

The strength, and wisdom of our ancestors has enabled us to walk in their footsteps towards our own healing, and walk the path of healing our Country. For this we thank you, our Martiinga Kuli Murrup (Ancestral spirits).

Today we walk our Culture knowing that when we strive for the balance of Bunjil’s creations, for us and for the future generations, you walk with us.

-Rebecca Phillips, descendant of Caroline Malcolm, Dja Dja Wurrung

In 1835 British squatters first made camp on the northern bank of the Yarra River. This was home to the Wurundjeri clan of the Woiwurrung people who called the Yarra ‘Birrarung’ - the ‘river of mists and shadows’.

‘Encampment of Aboriginal Australians along the bank of the Yarra’ by John Cotton, c.1845. Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria.

This scene shows daily life for the Woiwurrung people whose lands included Birrarung. It shows a woman with ritual scarification marks on her chest, wearing a possum-skin cloak.

‘The Settlement’ grows

‘The Settlement’ soon became a town. Land was sold and bush was cleared for the creation of roads and buildings.

In 1839 one visitor noted: ‘When I was here three years ago there were but two houses of any note whatever ... Now I find a town occupying an area of nearly a mile square, on which are some hundreds of houses…’

…grasslands lay for hundreds of kilometres to the west and north of Melbourne, into which squatters and their sheep made rapid forays - Historian, Richard Broome

The settlement grew quickly and expanded inland. Between 1836 and 1851 the settler population increased from 224 to 77,345. The number of sheep skyrocketed from 3,000 to 6,000,000!

no country for blackfellows like long time ago – Billibellary, Ngurungaeta (leader) of the Wurundjeri or Woiwurrung people

‘Billibellary’s young lubra with infant at her back’ by William Thomas, c.1839. Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria.

Billibellary was Ngurungaeta (leader) of the Wurundjeri or Woi wurrung people. His wife’s name is not now known, but the child was Susannah. Sadly, she died at the age of eight.

Billibellary was an important figure in early Melbourne. He was one of the Elders present at the signing of Batman’s Treaty in June 1835 and was a strong leader and advocate for his people. He often gave advice to Assistant Protector William Thomas. Thomas mourned his death in 1846: ‘I have lost in this man a valuable counsellor in Aboriginal matters’.

European settlement of the Port Phillip District devastated the Aboriginal population. European farming, violence and introduced disease severely weakened and scattered tribes, contributing to declining birth rates.

Dispossessed of their land and the food sources that had long sustained them, the First Peoples faced starvation. By the time gold was discovered in Victoria, the Aboriginal population had fallen to about 2,000.

In 1839 a ‘protectorate’ system was established in Port Phillip to convert and control Victoria’s Aboriginal people. Four assistant protectors, under chief protector G.A. Robinson, were appointed. Under the Protectorate, Aboriginal groups were encouraged to move to reserves of land established away from the town centres, but an indifferent colonial administration provided few resources for them. Aboriginal people protested their treatment and loss of land, to no avail.

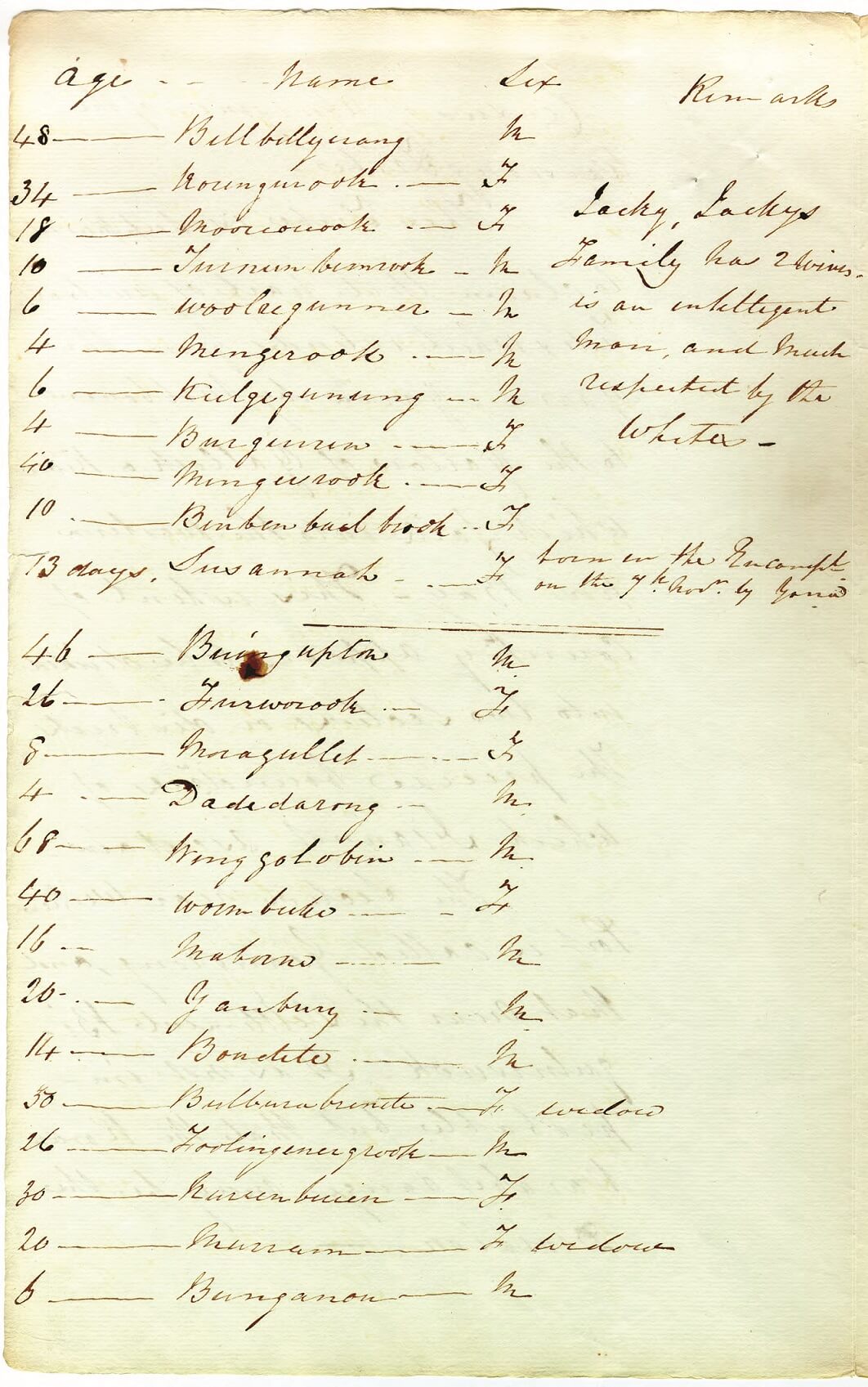

Extract from Assistant Protector William Thomas’ census of the Warworong (Woiwurrung) and Bonurong (Boonwurrung) tribes, 1839. Reproduced courtesy Public Record Office Victoria, VPRS 10/P0, unit 1, item 242.

William Thomas served as Assistant Protector of the Port Phillip and Westernport Districts. In November 1839 Thomas provided the first detailed census of the Warworong (Woiwurrung) and Bonurong (Boonwurrung) tribes. In his cover letter Thomas noted, ‘that the whole of the two tribes when united probably would not exceed two hundred and thirty’. Thomas later reported that the Boonwurrung and Woiwurrung, who numbered about 350 in 1835, totalled only 28 in 1857.

This page records the birth of Billibellery’s daughter, Susannah, ‘female born in the encampment on the 7th Nov. by Yarra’. She was just 13-days old when the note was made.

The full document can be viewed on the Public Record Office Victoria website.

Introduced sheep and cattle scared away the game, trampled the grasslands and waterholes and ate the root vegetables, such as murnong, that formed the First Peoples staple diet. Not unreasonably, Aboriginal people tried to ‘share’ the settler’s food - picking crops and killing livestock to replace their lost supplies. This sometimes led to violent clashes and reprisals.

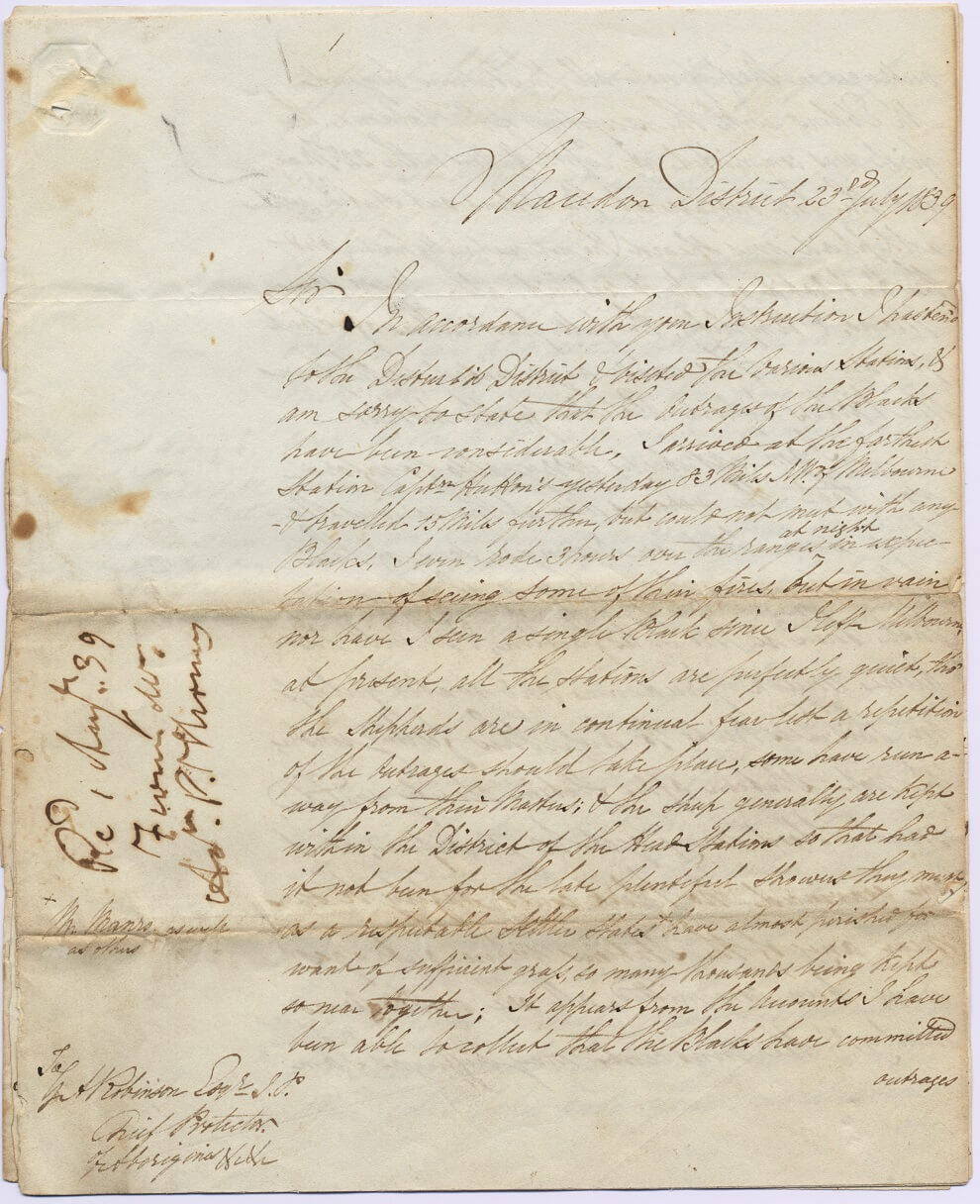

In 1839 William Thomas wrote to his superior, Chief Protector of Aborigines George Augustus Robinson, imploring him to help the ‘Wadawurrung’ People: ‘…the poor Natives cannot find it [murnong], thus they are reduced to the greatest extremity at this period of the year… it is only at this season of the year that outrages [violence] occur in this district an evident proof while they can get a sufficiency they will be harmless but the cravings of nature drives them to excess, tho’ I deplore the outrages they have committed, I cannot help commiserating their misfortune.’

Letter from Assistant Protector William Thomas to G.A. Robinson, Chief Protector of Aborigines, 1839. Reproduced courtesy Public Record Office Victoria, VPRS 13172/P1, unit 31.

Victoria’s Gold Rush

For many of Victoria’s First Peoples, the gold rush represented a second wave of dispossession. As settlements spread over the interior, Aboriginal people were further displaced, their camping sites and hunting grounds destroyed and their waterways polluted.

...we had quietness and greenness, and the most deliciously cool water, sweet and clear. But this quietness and greenness cannot last. Prospectors will quickly follow us. We foresee that all these bushy banks of the creek will be rapidly and violently invaded. The hop-scrubs will be burnt, the bushes in and on the creek cleared away, the trees on the slope felled, and the ground torn up for miles around. The crystalline water will be made thick and foul with gold-washing; and the whole will be converted into a scene of desolation and discomfort.

Author and miner, William Howitt

Among those most affected were the Wathaurung, near Ballarat, and the Dja Dja Wurrung from country near Bendigo in central Victoria. It is estimated that prior to European contact there were up to 3,240 members of the twenty-five Wathaurang clans. By 1861, only 255 individuals were recorded in the Ballarat area.

Against the odds, however, some individuals were able to adapt. Recent scholarship suggests that Aboriginal Victorians who survived the initial onslaught found some opportunities on the goldfields, including policing, guiding and, of course, finding gold.

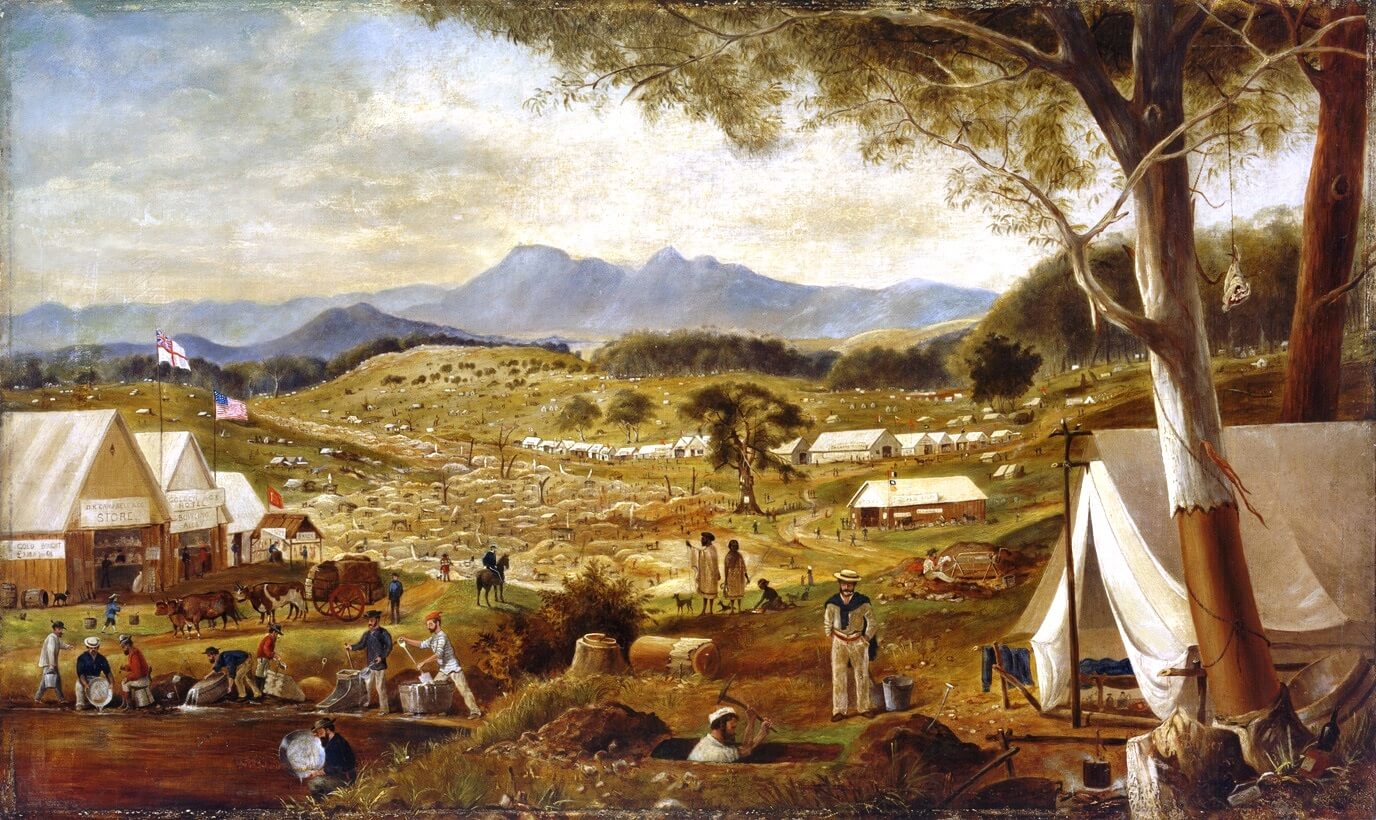

‘Gold diggings, Ararat’ by Edward Roper, c.1855. Reproduced courtesy State Library New South Wales.

Many diggers commented on the presence of Aboriginal family groups on the goldfields. Edward Roper’s painting of the Ararat diggings shows a group of Aboriginal people standing in the centre of the field. One of the figures is kneeling and could be panning for gold.

The impact on the environment is also clearly visible. Here we see a vast, largely treeless field, with mounds of unearthed clay. The landscape has been literally turned upside down by the diggers.

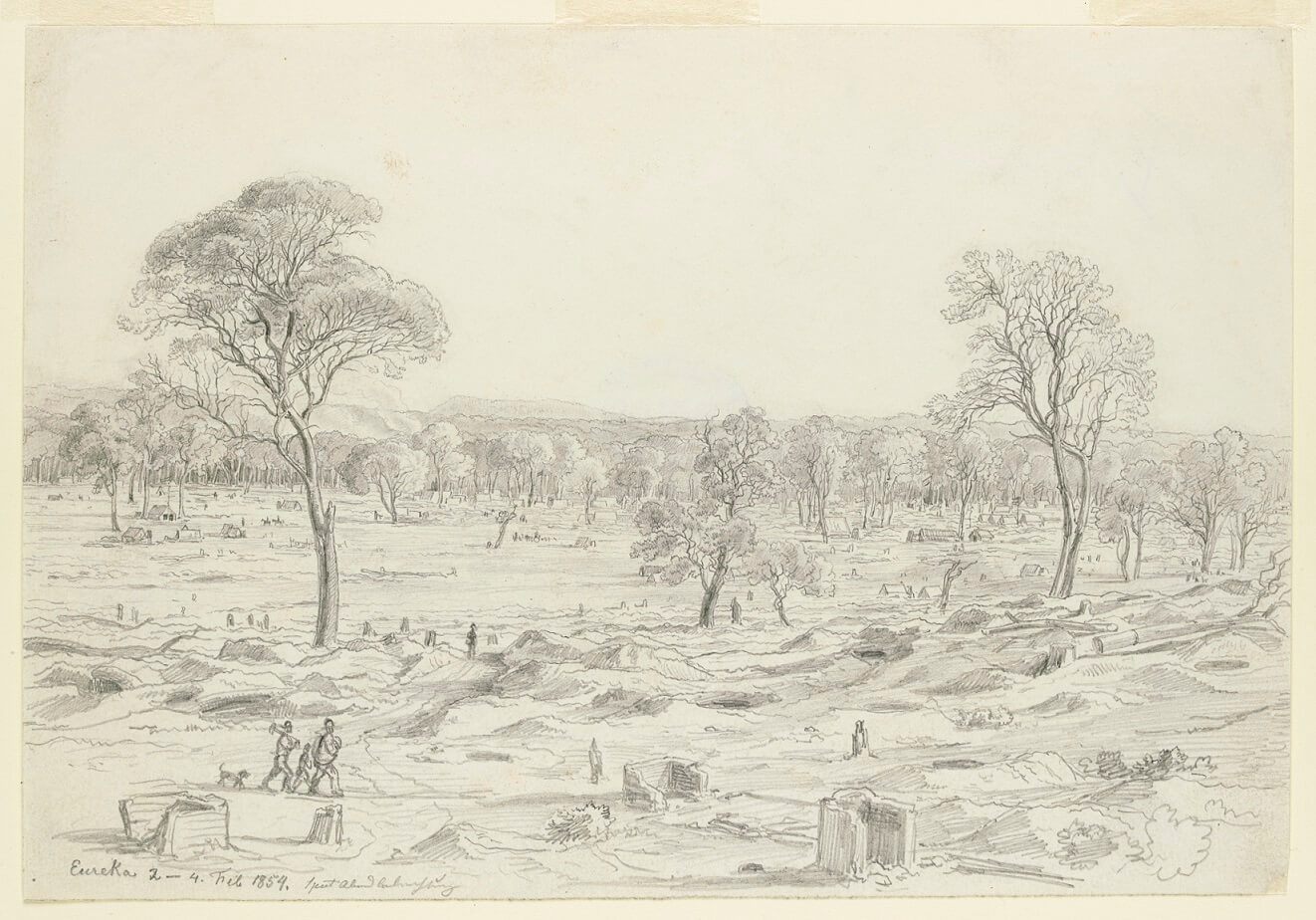

Sketch by Eugene von Guérard, 1854. Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria.

Most miners cared nothing for the environment they destroyed. Creeks and streams became muddied alluvial sites. Timber was felled and wildlife was hunted and shot. Author and miner, William Howitt, wrote in 1855: ‘The diggers seem to have two especial [sic] propensities, those of firing guns and felling trees. It is amazing what a number of trees they fell.’

Forced from the land that sustained them, Aboriginal families and communities suffered from widespread disease and depression. Birthrates fell drastically. Around Bendigo, Assistant Protector Edward Stone Parker reported only 25 births between 1843 and 1858.

Some colonists saw clearly what was happening on the frontier. Edward Wilson, editor of the Argus newspaper lamented in an editorial in 1856:

In less than twenty years we have nearly swept them [First People] off the face of the earth. We have shot them down like dogs. In the guise of friendship we have issued corrosive sublimate in their damper and consigned whole tribes to the agonies of an excruciating death. We have made them drunkards, and infected them with diseases which have rotted the bones of their adults, and made such few children as are born amongst them a sorrow and a torture from the very instant of their birth. We have made them outcasts on their own land, and are rapidly consigning them to entire annihilation.

Guiding the way

… after great difficulty we were happily enabled to complete a bargain with two of the natives to put us upon a track which would lead us to Forest Creek'. For this piece of service we would almost have given all the gold we had.

John Sherer, The Gold Finder of Australia, 1853

In an unfamiliar landscape many newcomers depended on Aboriginal guides to point the way to the goldfields. Local Aboriginal people located food, bush medicine and precious waterholes for horses and other stock. One miner, George Baker, was completely dependent on his guides when overlanding from Adelaide to the diggings at Castlemaine:

We started to go through the “short desert” taking with us two blackfellows with their lubras and picanninies [women and children] to show us where the water was. It was a very hot and windy day, and we had forgotten to take water with us. It was towards evening when the blackfellows found water, and we were in a very exhausted condition.

Shearers, scourers and timber cutters

Demand for labour was high on pastoral runs during the gold rush and many First Peoples took the place of white labourers.

At ‘Terinallum’ in the western district of Victoria, Aboriginal people made up some 75 per cent of the station’s workforce:

‘[F]or it is all Gold in this neighbourhood – every body totally Ignorant about wool … I am washing the sheep now. I have got a lot of Blacks engaged for washing, they are doing very well as yet.’

Aboriginal workers showed an aptitude for pastoral life. According to one newspaper, ‘blacks were employed and they turned out their shorn sheep in a far more satisfactory manner than the majority of whites so engaged’. The task of droving often fell to Aboriginal workers, who were described as ‘bold and daring riders and good bushmen and could pick up any stragglers [cattle] they might fall in with on their journey.’

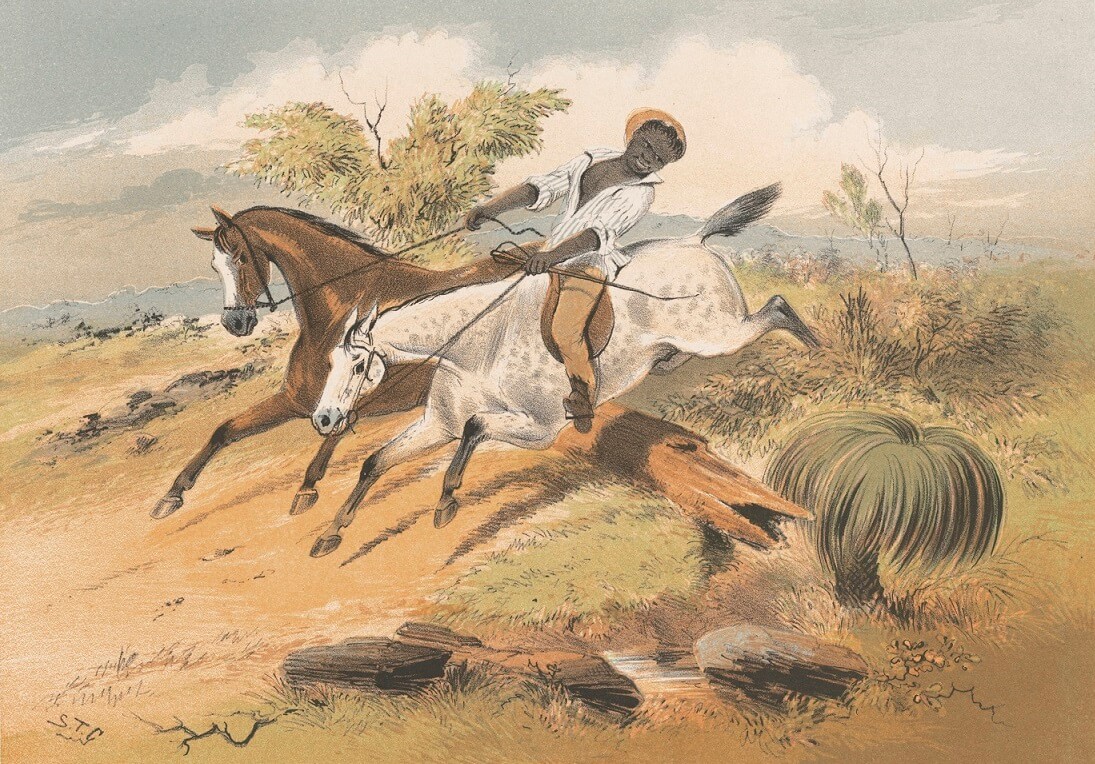

‘Squatters tiger’ by S.T. Gill, 1865. Reproduced courtesy National Museum of Australia.

‘Tiger’ was a nineteenth century term used to describe a young groom in charge of a gentleman’s horses.

‘Cattle branding’ by S.T. Gill, 1865. Reproduced courtesy National Museum of Australia.

Selling goods

First Peoples also adapted to the commerce of the goldfields, selling goods such as baskets, nets and dallong, heavy thick rugs or cloaks made from wollert (possum), goin (kangaroo) or tooan (flying foxes).

Dallong were highly sought after for their warmth. According to F. Hughes, a Castlemaine settler, possum skin rugs were ‘sold to settlers and lucky gold diggers at five pounds a-piece’. Miner G.H. Wathen spoke highly of an opossum-rug he purchased: ‘I was soon asleep on the ground, by the fire, under an overbowering banksia, wrapped in the warm folds of my opossum-rug’.

Aboriginal groups also quickly learned the value of the game they captured, trading it for money to hungry miners. Miner and author William Howitt, on the Campaspe River, observed ‘a number of natives fishing here, who had caught a good quantity of the river cod, and had learned to ask a good price for it’.

‘Ballarat, Victoria’ by S.T. Gill, c.1854. Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia.

Two Wathawurrung people, one carrying goods, on what is now Main Road Ballarat.

Finding gold

Aboriginal people quickly appreciated the value of gold and proved to be expert gold seekers. One miner described Aboriginal parties ‘busy knocking out stone from a [quartz] reef’, whilst a journalist wrote of their success: ‘The Aborigines of this district seem to have a peculiar faculty for picking up valuable nuggets of gold… They say, “whitefellow dig for gold, and blackfellow pick it up”’.

In fact some of the Victorian diggings were ‘discovered’ by First Peoples. In September 1852 Paul Gooch, a miner in the Canadian and Prince Regent gullies, reported in the Geelong Advertiser the discovery of the famous Eureka Lead in Ballarat:

The way in which the Eureka diggings were discovered was on the occasion of my sending out a blackfellow to search for a horse who picked up a nugget on the surface. Afterwards I sent out a party to explore who proved that gold was really to be found in abundance.

Law and order

The Native Police Corps played an important part in the gold rush story. The Corps was established in February 1842 by Henry Edmund Pulteney Dana. More than 100 Aboriginal men joined, recruited initially from the Boonwurrung and Woiwurrung clans, but later from all areas of the Port Phillip District.

Members of the Corps were given horses, uniforms and weapons, food and accommodation. They were promised a salary of three pence a day (about one quarter of a shepherd’s wage), but only the European officers were paid regularly.

Their duties were wide-ranging - finding people lost in the bush, escorting travellers, tracking bushrangers and other criminals and delivering mail. They were also the first police force on the Ballarat goldfields, arriving on 20 September 1851.

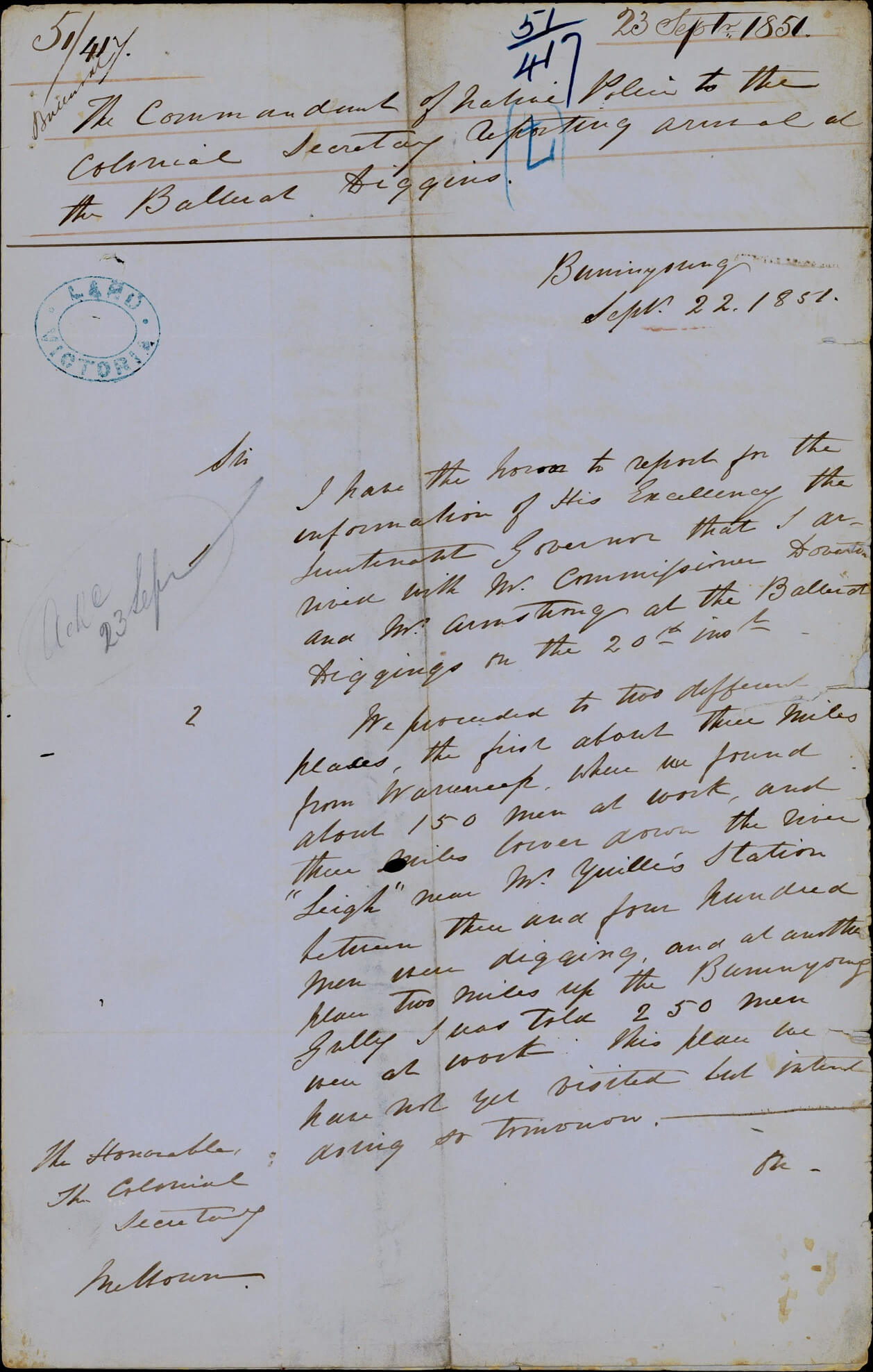

Superintendent of the Native Police Corps, Henry E. Pulteney Dana, to the Colonial Secretary, reporting his arrival to the Ballarat diggings, 22 September 1851. Reproduced courtesy Public Record Office Victoria, VPRS 2878/P0, unit, item 417.

On 21 September 1851 Dana and the Native Police troopers arrived at Ballarat to announce a new licence fee and issue monthly licences. Unsurprisingly the miners ‘appeared very much dissatisfied’ with this new tax. A public meeting was organised and speakers ‘attempted to pass resolutions and tried in their speeches to induce the people to resist the payment of Licenses’. After the meeting some men attempted to pay for their licences, but were attacked by an angry mob. Dana praised the intervention of the Native Police, who prevented serious injury.

On the goldfields

Their duties included the unpopular tasks of checking licences and collecting licence fees. Miner William Brownbill, arrested in 1851 for digging without a licence, described being guarded ‘by eight or nine black troopers, who in their uniform, and polished boots, looked as proud as possible.’ The Native Police also provided armed escorts for gold destined for Melbourne.

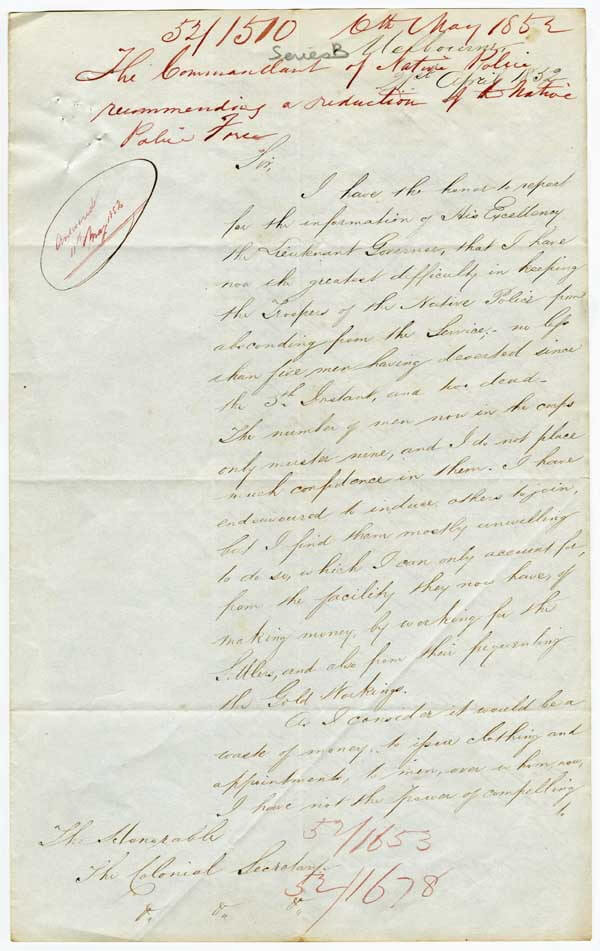

Superintendent of the Native Police Corps, Henry E. Pulteney Dana, reporting to the Colonial Secretary, 21 April 1852. Reproduced courtesy Public Record Office Victoria, VPRS 1189/P0, unit 16, item 52/1510

The lure of gold and the opportunities offered on the goldfields took their toll on the Native Police Corps. By April 1852 Aboriginal troopers were ‘absconding’. ‘I can only account for [this],’ Dana writes in this document, ‘from the facility they now have of making money by working for the Settlers, and also from their frequenting the Gold Workings.’

Authority

Attitudes to the Native Police Corps varied: some reflected prevailing racism. The presence of the Corps certainly angered some miners: they enforced the hated licencing system and there were reports of rough treatment from Dana and some troopers. One miner openly scoffed at the idea of them guarding the gold from Ballarat.

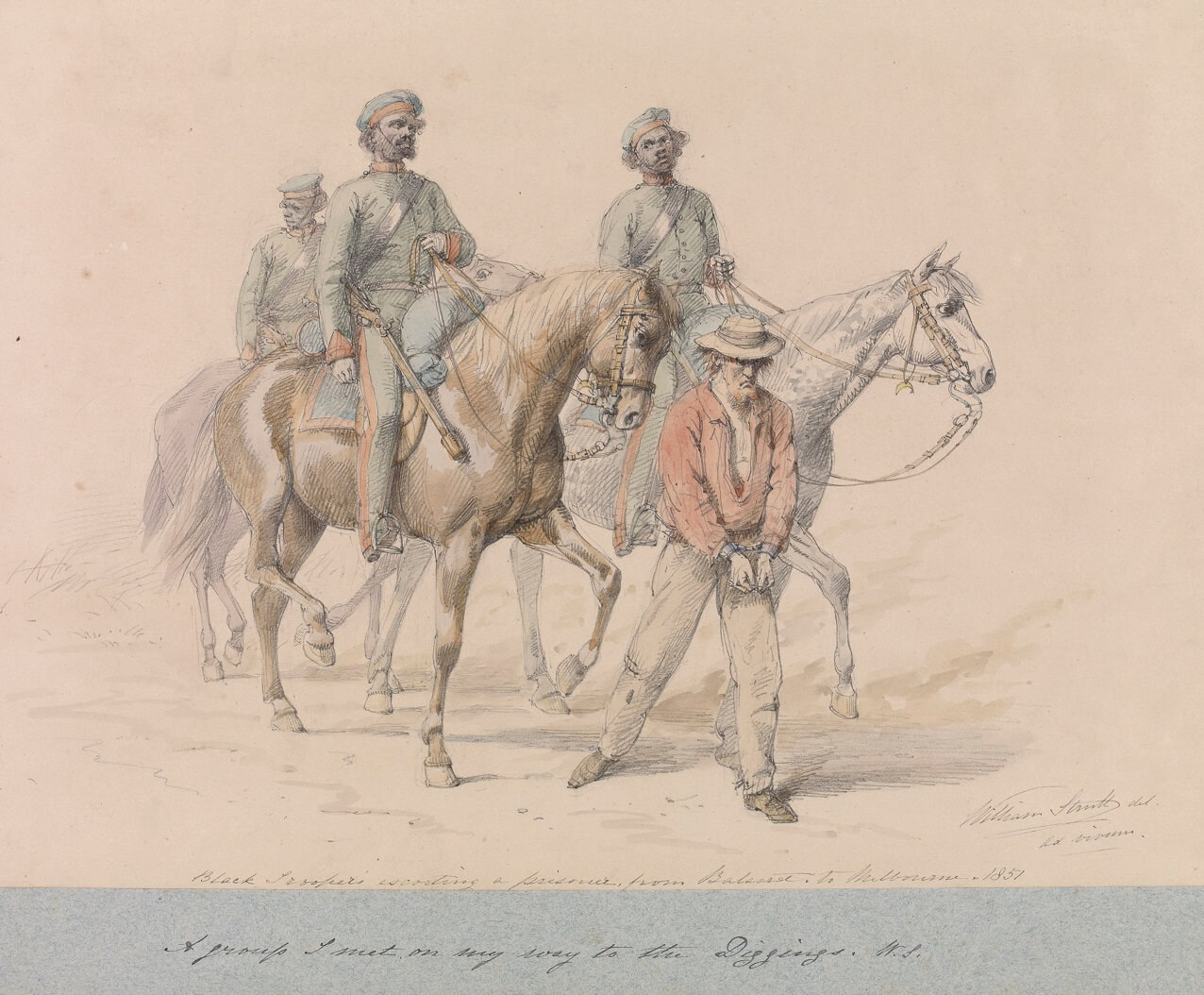

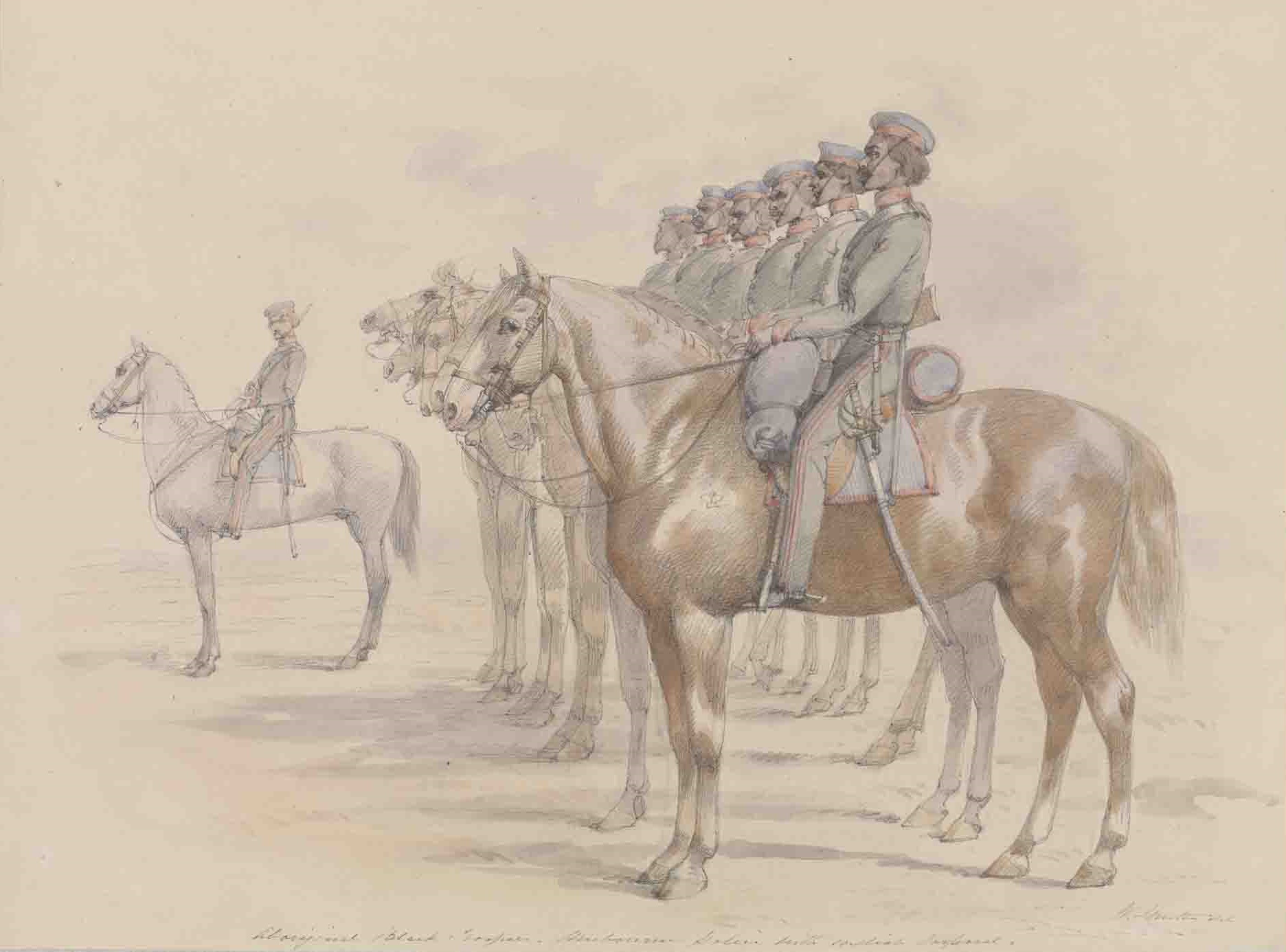

Watercolour by William Strutt. Reproduced courtesy Victorian Parliamentary Library.

The Native Police were more than a force for law and order. Troopers searched for those lost in the bush and tracked down bushrangers and criminals. Artist William Strutt wrote of this work: ‘With my friend M. walked on to the diggings. Met on our way a prisoner and a villainous squint-eyed scoundrel he looked… escorted by two well mounted and smart looking black troopers…’

Others, like artist William Strutt, openly admired the Corps. Strutt described them as ‘a useful set of men… they seemed to lend themselves wonderfully to military discipline, and as to their riding, you could literally say that man and horse were one’.

Watercolour by William Strutt. Reproduced courtesy Victorian Parliamentary Library.

William Strutt arrived in Victoria in the 1850s. One of his earliest commissions was to sketch and engrave the portraits of members of the Native Police Corps. Strutt spent many days at the Richmond Police Paddock sketching the men, their horses, uniforms and equipment.

This image, Aboriginal Black Troopers, Melbourne Police with English Corporal (1851), is accompanied by the following text: ‘Black troopers drilling. This valuable force, so useful as bush trackers, were disbanded at the discovery of gold. These men … were splendid horsemen’.

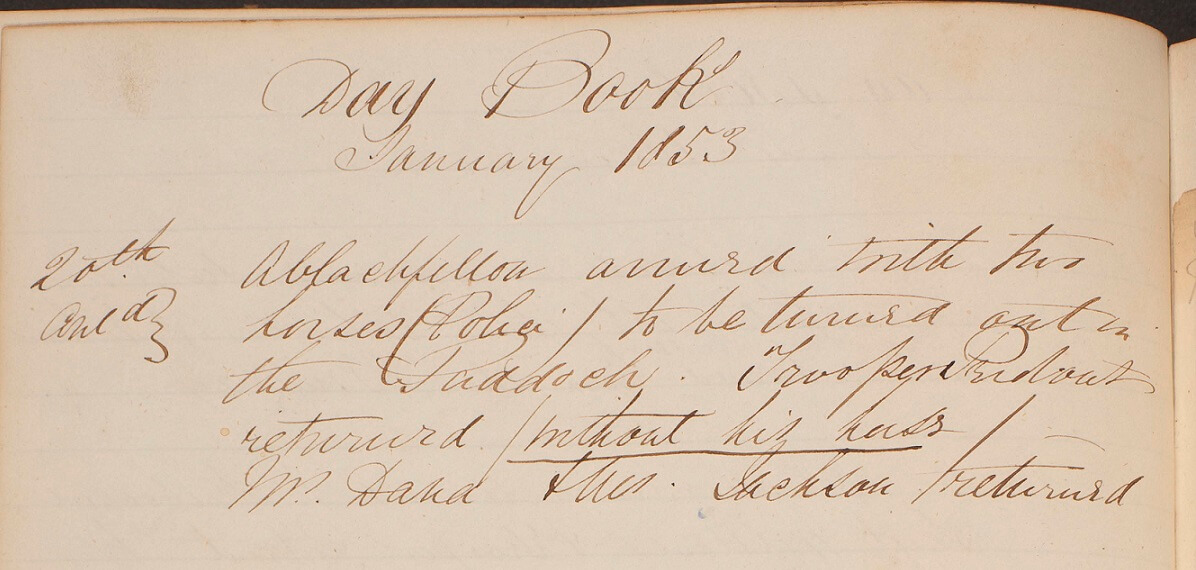

A Day Book from the Corps’ headquarters at Narre Warren for the period 1845-53 is held by Public Record Office Victoria. It outlines the varied day-to-day activities of the Corps – from parading and chores such as cleaning equipment and digging potatoes, to guarding the penal stockade at Pentridge, tracking escaped prisoners and pursuing bushrangers.

Dana died in November 1852 and the Native Police Corps was disbanded shortly afterwards. A final entry in the Day Book on 20 January 1853 suggests an abrupt ending: ‘A blackfellow arrived with his horse (police) to be turned out in the paddock’.

After the Gold Rush

By the late 1850s it was obvious that the Aboriginal population was in crisis. A Select Committee of the Legislative Council (comprised only of white men) was appointed to consider what to do.

The solution suggested was to confine Aboriginal people to a series of land reserves or missions, under the control of a Central Board for the Aborigines. While some First Peoples opposed these reserves, others saw them as a refuge of sorts. But as time went on Aboriginal people lost almost all their rights to self-determination. The Aborigines Protection Act 1869 (Vic) created an alternative Board for the Protection of Aborigines, with sweeping powers to control all aspects of Aboriginal life. In particular it allowed the Board to remove Aboriginal children from their families. The Board continued in operation until 1957.

First Peoples and the Gold Rush was researched and curated by the Old Treasury Building in partnership with the Dja Dja Wurrung Clans Aboriginal Corporation and Public Record Office Victoria.

With special thanks to

Dr Fred Cahir, Federation University

Wurundjeri Woi Wurrung Cultural Heritage Aboriginal Corporation