Chaos followed the discovery of gold in Victoria in 1851. Bustling towns appeared almost overnight and government struggled to maintain law and order.

A licence to dig

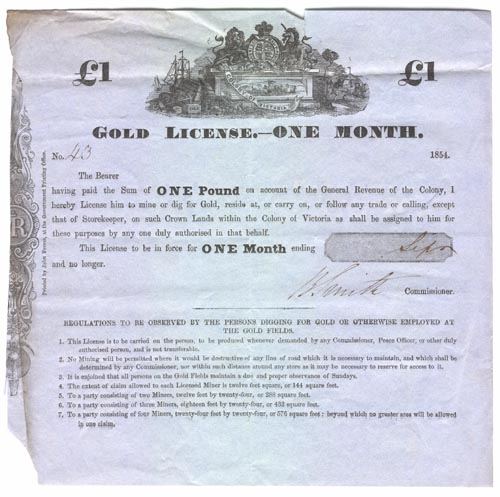

The tiny colonial administration was overwhelmed. To keep some control over the gold seekers and help pay for the administration of the goldfields, Lieutenant-Governor La Trobe introduced gold licences in September 1851. Miners paid 30 shillings per month (later reduced to £1 per month or £8 per year) for the right to dig a small ‘claim’, usually about eight feet square (2.4m²).

Not surprisingly the licence system was unpopular. The licence was expensive – 30 shillings was a substantial sum for most diggers, who might spend months digging for gold without success.

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria.

This gold licence cost 30 shillings and was valid for only one month. By contrast squatters could hold 20 square miles of land for an annual tax of 10 pounds!

The licence allowed the bearer to 'mine or dig for Gold, reside at, or carry on, or follow any trade or calling, except that of Storekeeper' on land designated as a gold claim.’

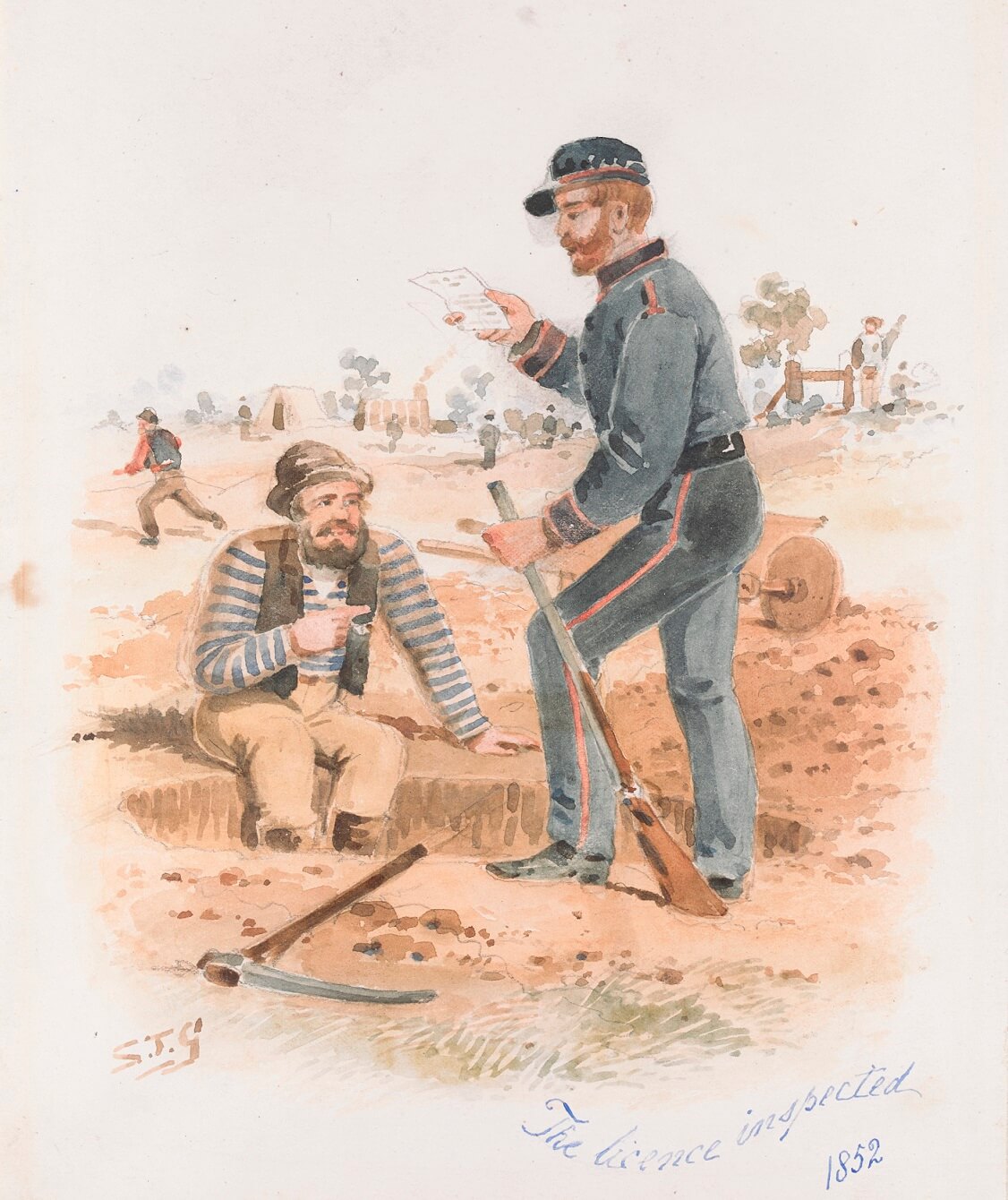

Gold commissioners, assisted by police, ran ‘licence hunts’ tracking down miners who had not paid their fees. Licences were to be carried at all times and little leniency was shown. The system was also open to abuse. Without a licence diggers could be fined or gaoled, and police were able to claim half of the fine as a reward. Wrongful arrest, perjury and even blackmail occurred and normal policing was neglected.

Mounting tensions

Resistance to the licence fee spread throughout the fields. The first protest meeting was organised at Buninyong on 25 August 1851. Alfred Clark, a reporter for the Geelong Advertiser, attended the meeting and wrote:

Tonight for the first time since Australia rose from the bosom of the ocean, were men strong in their sense of right, lifting up a protest against an impending wrong, and protesting against the Government. Let the Government beware!

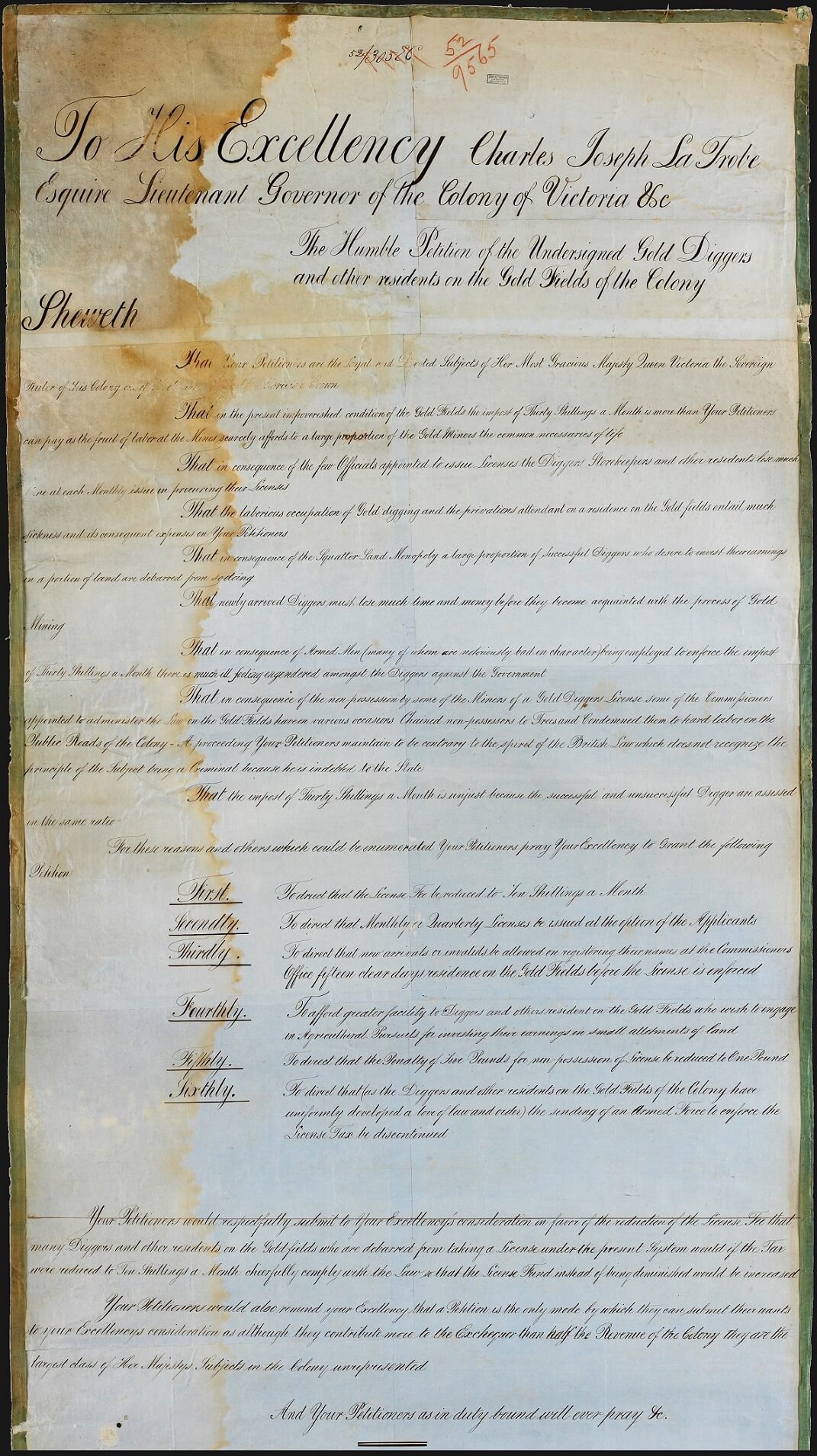

A Miner’s Association was formed at Mount Alexander (Castlemaine) in December 1851 and at Bendigo in 1853 the Red Ribbon Rebellion was led by the Anti-Gold Licence Association. Diggers wore red ribbons in their hats as a sign of protest, refused to pay their licences and collected a ‘monster’ petition which was presented to Lieutenant-Governor La Trobe. The petition demanded immediate reform of government administration, a reduction in the licence fee, the right to vote and land reform (with poor returns from diggings, miners wanted affordable land on or near the goldfields).

A constitution for Victoria was being developed in the early 1850s. At issue was the all-important question of suffrage – who could vote to elect members of parliament. In 1851 Victoria had a single Legislative Council chamber, with one third of the members nominees of the Lieutenant-Governor and the others elected on a restricted property franchise. This kept legislative power in the hands of wealthy property-owning men. Agitation on the licence question soon merged with wider demands for democratic reform. The miners began to claim ‘No taxation without representation’!

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria.

In December 1851 the government moved to double the licence fee. On 15 December an estimated 15,000 angry diggers attended a Monster Meeting at Forest Creek in Castlemaine to protest. Two days later the government revoked the increased fee.

The lure of gold attracted a diverse group to the diggings. Some had been politically involved in movements such as Chartism in England or political revolutions throughout Europe. These men brought ideas such as equal rights and votes for all (men).

Chartism was a working class movement which emerged in Britain in the 1830s. The aim of the Chartists was to gain political rights and influence for working class men. Chartism got its name from the formal petition, or People’s Charter, that listed the six main aims of the movement. These were:

1. a vote for all men (over 21)

2. the secret ballot

3. no property qualification to become an MP

4. payment for MPs

5. electoral districts of equal size

6. annual elections for Parliament.

Political deliberation is the poor man's right arm. It brought the Magna Carta to the barons, Catholic emancipation to the Irish, and triumphant repeal of the Corn Laws for the people of England. Surely it would bring democracy to the gold diggers of Victoria.

George Thomson, Chartist and Leader of the Red Ribbon Movement, August 1853

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria.

Miners involved in the Red Ribbon movement organised the Bendigo Petition in mid-1853. More than 5,000 diggers signed the petition, which was more than 13-metres in length. The petition, calling for a reduction in monthly licence fees and land reform for diggers, was presented to Lieutenant-Governor La Trobe on 1 August 1853.

At Ballarat, the tension between miners and government representatives increased dangerously.

6 October 1854 - Fire at the Eureka Hotel

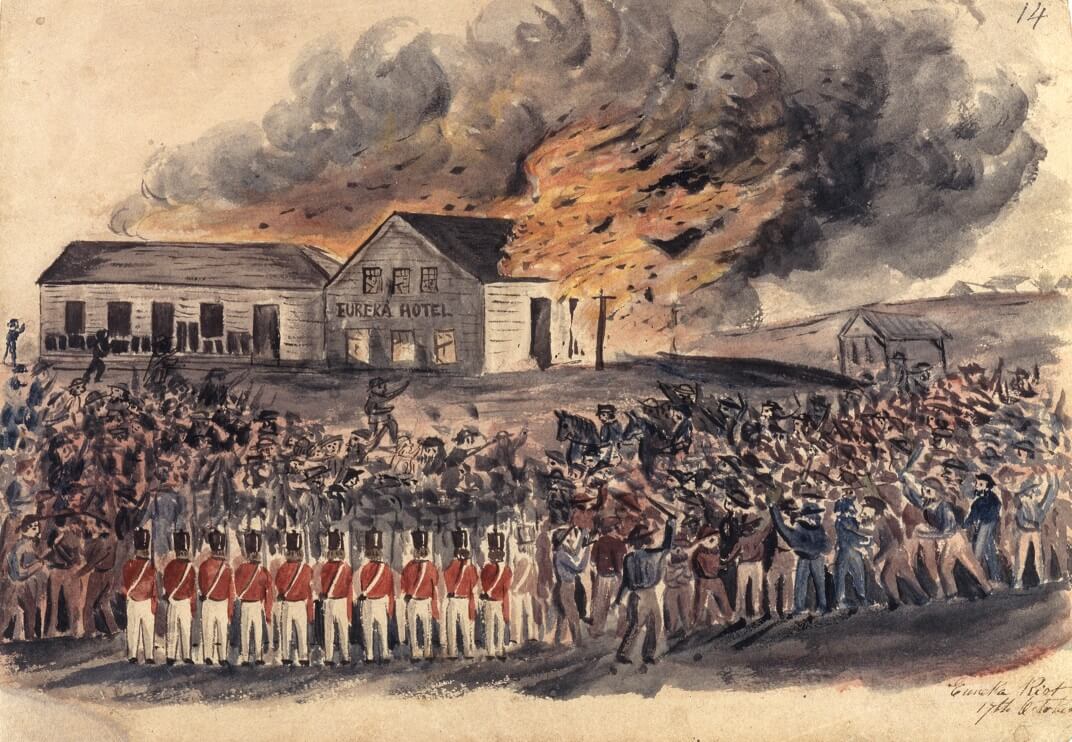

On 6 October 1854 a young digger, James Scobie, was murdered outside the Eureka Hotel. Suspicion fell on the publican, James Bentley, an ex-convict from Van Dieman's land (Tasmania). Bentley was arrested but, despite his evident guilt, was exonerated after a brief hearing. The presiding magistrate was John Dewes, a friend rumoured to be a business partner of Bentley.

17 October 1854

With news of Bentley’s release a crowd of thousands gathered near the Eureka Hotel. Tempers flared and the hotel was burnt to the ground.

‘Eureka Riot 17th October (1854)’ by Charles A Doudiet. Reproduced courtesy Art Gallery of Ballarat.

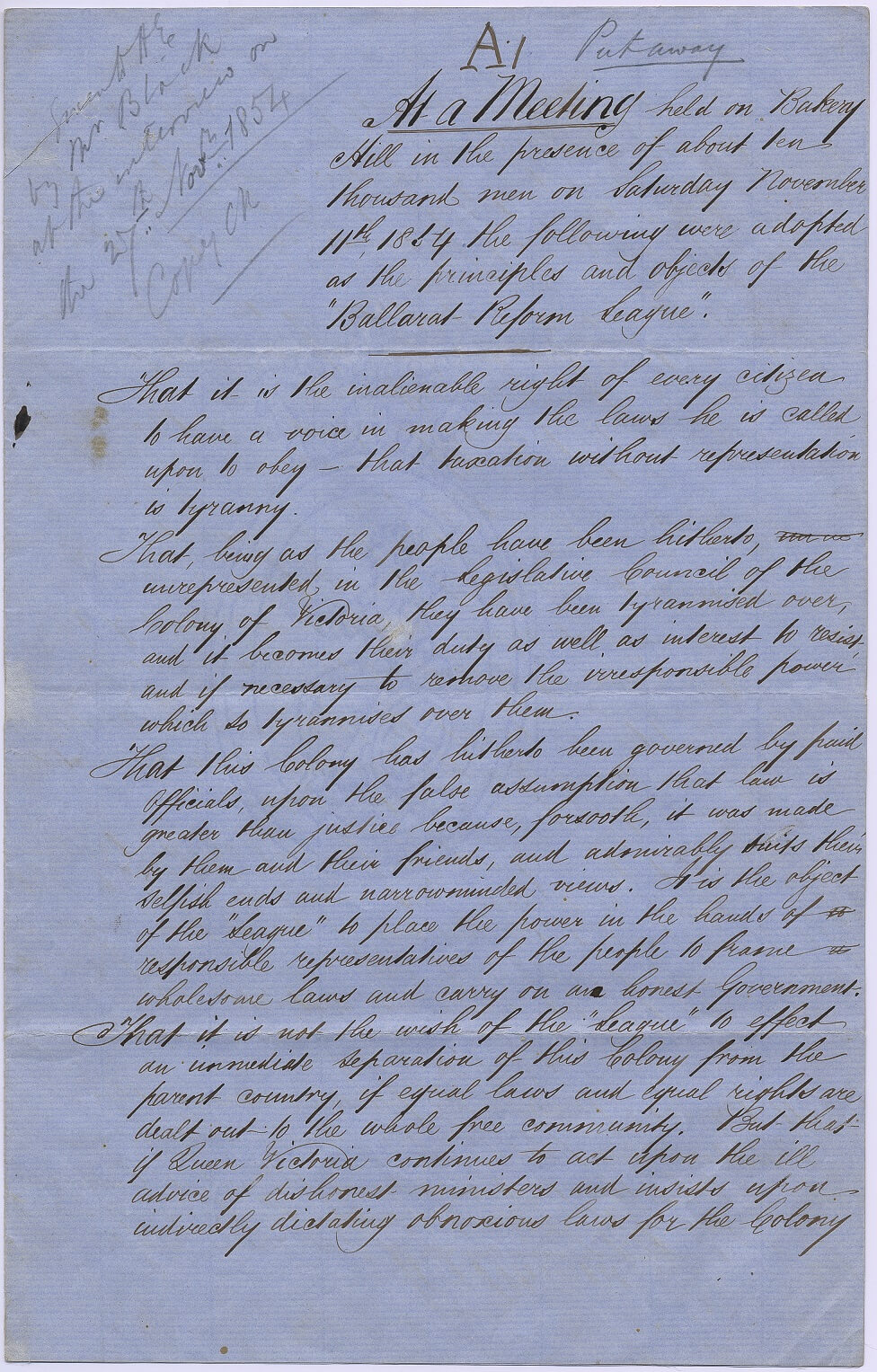

11 November 1854 - The Ballarat Reform League

On 11 November 1854 the miners held a mass rally at Bakery Hill in Ballarat. Here, the Ballarat Reform League was formed.

The League drafted a four-page charter calling for fair representation for the goldfields in the Legislative Council, no property qualifications for MPs, payment of members and manhood suffrage (votes for all men). The Charter also demanded the immediate ‘disbanding’ of the Gold Commissioners and the ‘total abolition of the diggers’ and storekeepers’ licence tax’.

Reproduced courtesy Public Record Office Victoria.

That it is the inalienable right of every citizen to have a voice in making the laws he is called upon to obey – that taxation without representation is tyranny.

In both the language of the Charter and its principal demands the Ballarat Reform League drew on the immediate legacy of the British Peoples’ Charter and the language of the American Declaration of Independence. It failed to convince Governor Hotham, who eventually moved against the miners in force at the Eureka Stockade.

In 2006, the Charter was inducted into the UNESCO Memory of the World Register of significant historical documents.

27 November 1854

The League presented the new Lieutenant-Governor Charles Hotham with the charter and demanded the release of three miners imprisoned for setting fire to Bentley’s hotel. The delegation was unsuccessful. Fearing a miners’ rebellion, the Gold Commissioner at Ballarat called for extra troops.

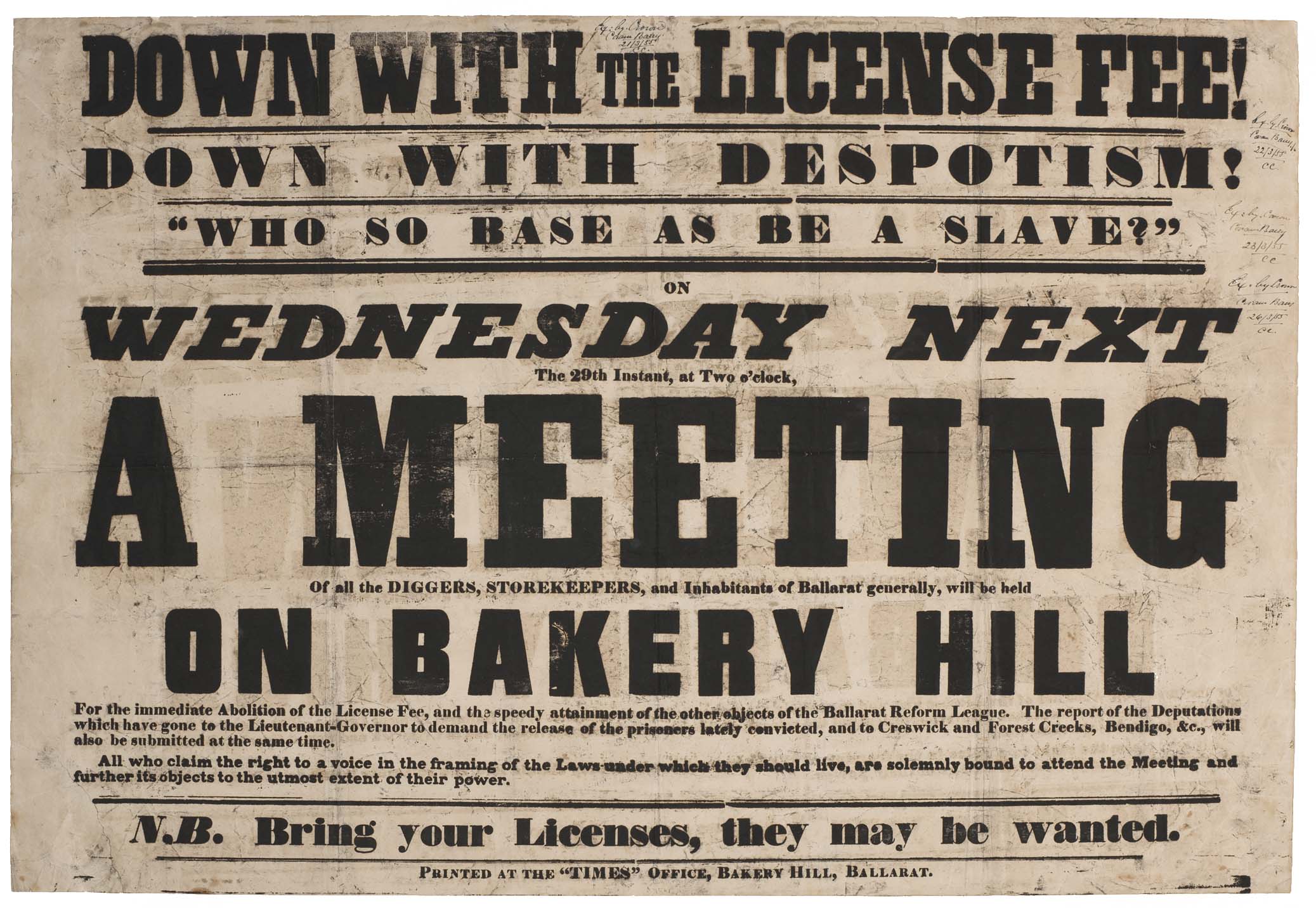

29 November 1854

More than 10,000 angry miners rallied at Bakery Hill in Ballarat. The Southern Cross (‘Eureka’) flag was flown for the first time and gold licences were burned.

Reproduced courtesy Public Record Office Victoria, VPRS 5527/P0, unit 4, item 1

Original meeting placard rallying ‘the inhabitants of Ballarat’ to Bakery Hill on 29 November 1854. Reports suggest that 10,000 people, about one third of Ballarat’s population, attended the meeting.

30 November 1854

Anger grew as the colonial government refused to compromise. Miners in Ballarat gathered again under the Eureka flag, electing Peter Lalor as leader. He led the men and women in an oath:

We swear by the Southern Cross to stand truly by each other, and fight to defend our rights and liberties.

Using timber from nearby mining shafts, the miners built a stockade and prepared to defend it.

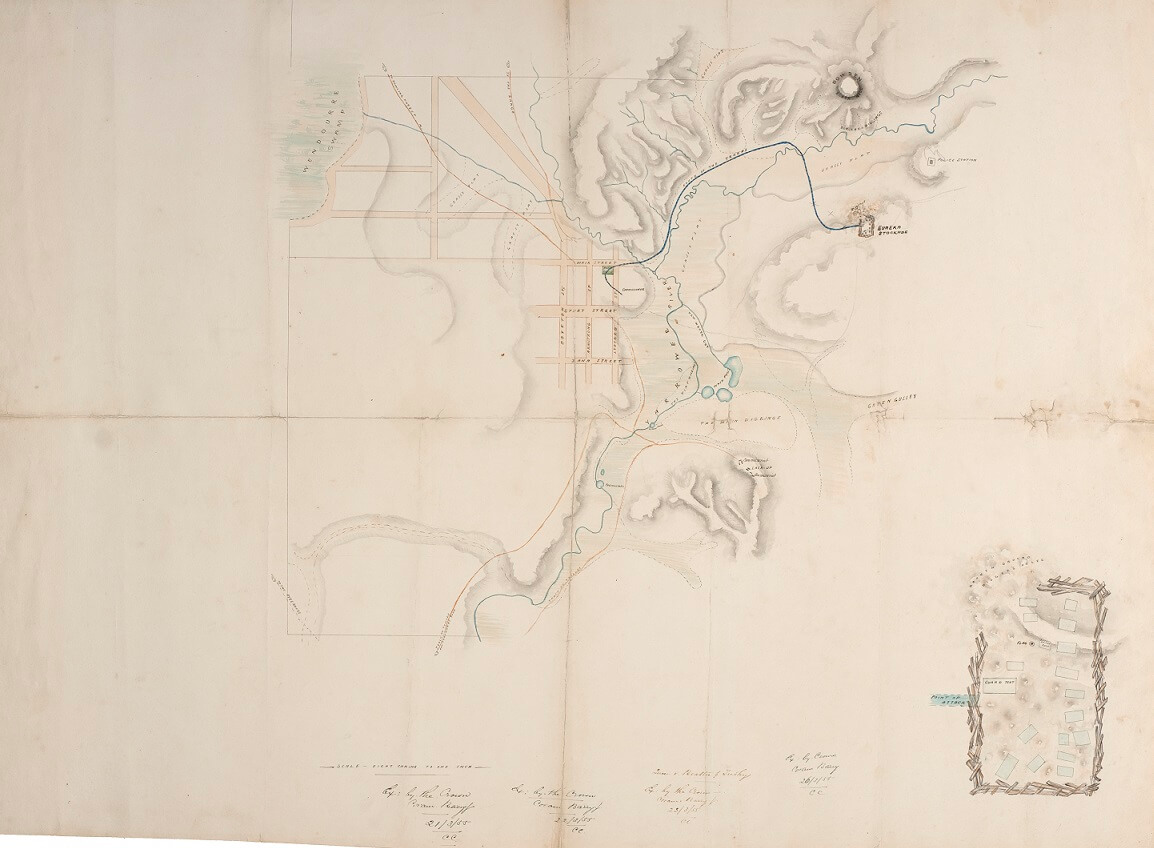

Reproduced courtesy Public Record Office Victoria

This map was an exhibit at the 1855 treason trials of thirteen stockaders. It shows the route taken by government troops to the miners’ stockade at the Eureka diggings in the early hours of 3 December 1854. There is a detailed drawing of the stockade itself.

The maker is unknown and its accuracy was questioned in court. The precise location of the stockade remains a subject of debate.

3 December 1854 - Attack on the stockade

Early on the morning of Sunday 3 December, with the stockade only lightly guarded, government troops attacked. Almost 300 mounted and foot troopers and police stormed the stockade. Outnumbered and trapped, the miners were overpowered almost immediately. Some 22 diggers and six soldiers were killed. The Geelong Advertiser later reported that ‘the corpses of the slain had been hacked by the mounted troopers out of sheer brutality… It was a needless massacre.’

The most harrowing and heartrending scenes were amongst the women and children I have witnessed through this dreadful morning. Many innocent persons have suffered, and many are prisoners who were there at the time of the skirmish but took no active part [...] At present every one is as if stunned, and but few are seen to be about. The flag of the diggings, "the Southern Cross," as well as the "Union Jack," which they had to hoist underneath, were captured by the foot police.

The Argus, 19 December 1854

‘Eureka Stockade Riot’ by J.B. Henderson, 1854. Reproduced courtesy State Library of New South Wales.

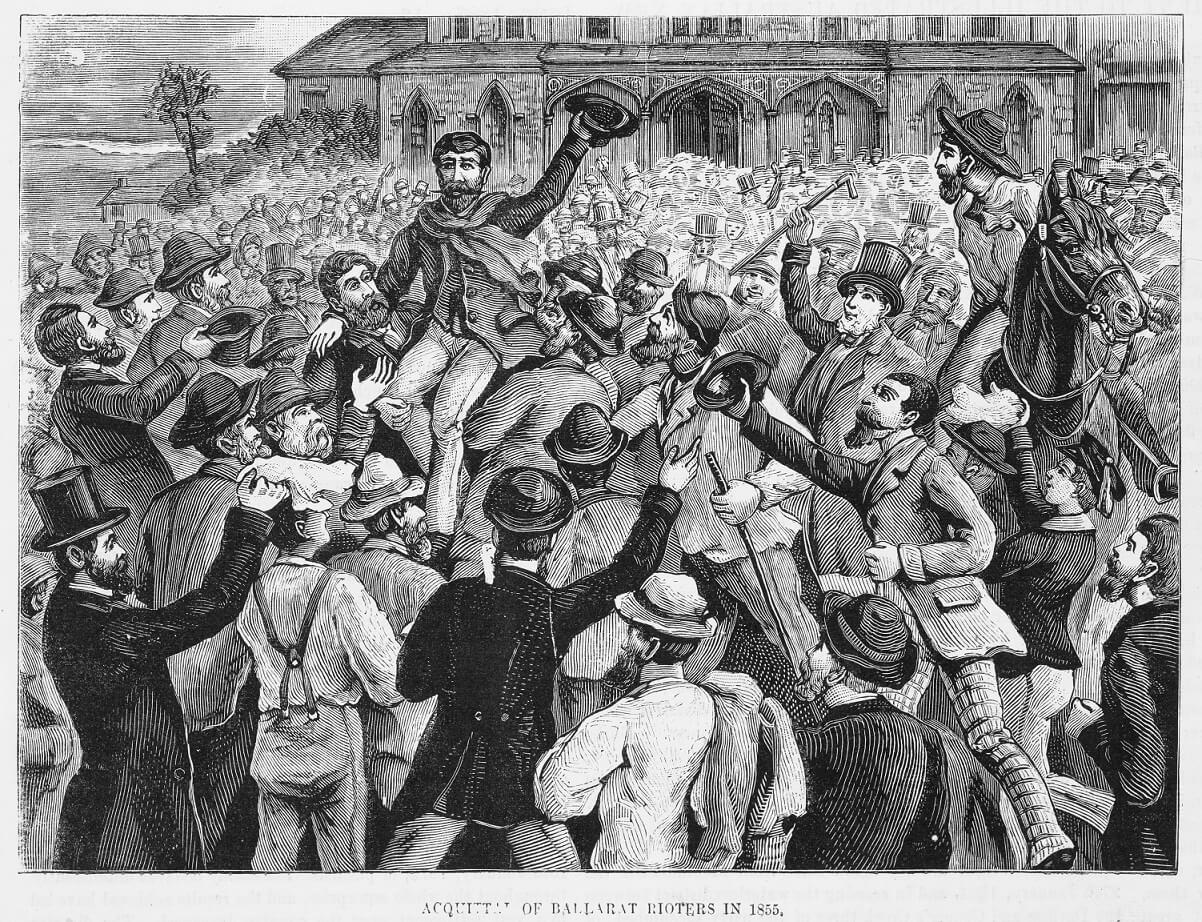

After Eureka

13 miners were arrested and taken to Melbourne to stand trial. But the savage actions of the government had provoked a popular backlash amongst many Victorians and all thirteen leaders of the uprising were acquitted by their juries at trial.

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

The freed men paraded through the streets of Melbourne, cheered by thousands of people.

Governor Hotham called for a Goldfields Commission of Enquiry. Recommendations included the removal of the licence fee, to be replaced by an export duty and a nominal £1 per year Miners’ Right. Half of the police on the goldfields were sacked, as were the gold commissioners, many of whom were found to be corrupt.

Twelve new members were added to the Victorian Legislative Council, four appointed by the Queen and eight by those diggers who held a Miner’s Right. One of these members was Peter Lalor who had survived the Eureka clash, though he lost an arm.

Lithograph by Ludwig Becker, 1856. Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

Irish-born Peter Lalor (1827–1889) emerged as a leader of the Ballarat miners in November 1854. He directed miners as they prepared their rough stockade at Eureka and swore to defend their rights. In 1856 Lalor became a member of Victoria’s first Legislative Assembly. Never a true Radical, he became progressively more conservative. He resigned from Parliament in 1887.

Women and political agitation on the goldfields

Most accounts of goldfields politics revolve around the words and actions of men. This is not surprising. Mid-nineteenth century social convention excluded women from public life almost entirely. But there were women on the goldfields who pushed against these conventions and the historical record hints at women active in the political movements, even if they remained in the background.

‘Universal suffrage’

The Ballarat Reform League Charter called for ‘manhood suffrage’ – the right of all adult men to vote. But for one brief moment in 1854 the far more radical proposal of ‘universal suffrage’, the right of all adults including women to vote, was put forward by radical painter and miner William Dexter. His wife Caroline was a prominent radical and supporter of women’s emancipation in England. There is no record that Dexter’s proposal was ever considered seriously by the Reform League, and this first brief reference to women’s suffrage in Victoria has largely been forgotten, but it is a reminder that women could be influential, even if their influence was unseen.

Who made the Eureka flag?

This is a much-vexed question. The short answer is that nobody knows. It has been suggested that local women probably sewed the flag and the names of several have been put forward. They include Anne Duke, Anastasia Withers and Anastasia Hayes, although the supporting evidence for these claims is sparse and contradictory. It is equally possible that goldfields flag makers Darton and Walkers were commissioned to make the flag and that Mrs Walker was one of the makers. We may never know.

Women at the Stockade?

Similar conjecture surrounds claims that several women were inside the Eureka Stockade when it was stormed. But what does seem clear is that goldfields women played an active part after the battle. They tended injured rebels, assisted the surgeons, and hid rebels from the police in the days that followed. Some like Clara Seekamp found a belated opportunity to take a public role. When her husband Henry, editor of the Ballarat Times, was arrested and gaoled for ‘sedition’ in December 1854, Clara took his place, writing a series of outspoken editorials in defence of liberty and reform.